Degree of stenosis

Description

Mild

Anal canal allows insertion of a lubricated finger or medium anoscope

Moderate

Insertion of a finger or medium anoscope requires dilation

Severe

Insertion of the little finger or small anoscope requires forced dilation

Level of stenosis

Description

Low

> 5 mm distal to the dentate line

Middle

5 mm distal to the dentate line extending to 5 mm proximal to the dentate line

High

> 5 mm proximal to the dentate line

Diagnosis

The evaluation and diagnosis of anal stenosis following hemorrhoidectomy starts with a thorough history and physical examination. The most common presenting symptoms are pain with defecation, constipation, narrow stool caliber, and, less commonly, bleeding [19, 20]. Fear of defecation may also be present. Often many of these symptoms overlap. Additionally, patients may present with fecal leakage or paradoxical diarrhea in the presence of obstructive symptoms or fecal overflow around impacted stool. These symptoms, combined with a history of hemorrhoidectomy, should prompt the clinician to consider the diagnosis of anal stenosis prior to examination.

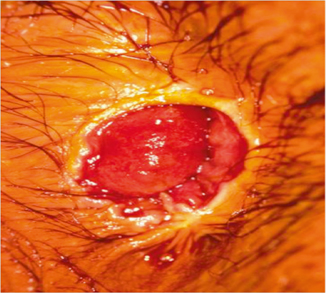

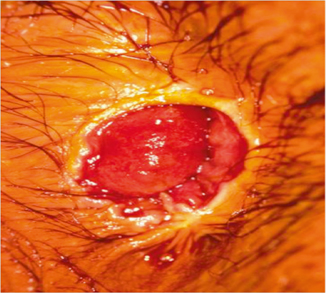

Physical examination confirms the diagnosis. On visual inspection, patients may have a circular narrowing or scar-like appearance to the anal aperture (Fig. 44.1) [21]. Digital rectal examination is often difficult to perform and may be very painful, and therefore, many patients will require examination under anesthesia (EUA) to perform a complete examination. Any suspicious lesions can also be biopsied at this time to rule out other more concerning issues including neoplasia. Anoscopy as well as proctoscopy should be performed, if not previously performed or in cases where another diagnosis is being entertained. An EUA may also aid in differentiation between functional and anatomic disorders of the anal canal [21]. Functional anal stenoses are the result of impaired relaxation of the internal sphincter complex without evidence of external anal scarring. Anatomic anal stenoses are those that are the result of scarring/contracture of the anal canal structure itself. Often there are components of both functional and anatomic stenoses in each patient.

Fig. 44.1

Anal stenosis with ectropion, also known as whitehead deformity. (Courtesy of Ira J. Kodner, MD)

No adjunctive testing is routinely necessary beyond a thorough examination of the anal canal unless indicated to evaluate other issues or the diagnosis is in question after examination. Anal manometry and/or defecography can be utilized to rule out other pelvic floor or functional disorders causing tenesmus, constipation, and/or fecal leakage [22].

Classification of Stenosis

The severity of anal stenosis is classified as mild, moderate, or severe based on the physical examination. Stenoses are considered mild if the anal canal can be examined by a lubricated finger or a medium anoscope, moderate if insertion of a lubricated finger or medium anoscope requires forced dilation, and severe if insertion of the little finger or a small anoscope requires forced dilation. The level of stenosis is related to the distance from the dentate line. Stenoses greater than 0.5 cm distal to the dentate line are considered low; those that are between 0.5 cm distal and 0.5 proximal to the dentate line are considered middle; and those greater than 0.5 cm proximal to the dentate line are considered high (Table 44.1)[18]. Both the level of involvement and the severity of stenosis are important when developing the plan for managing these patients.

Treatment

Prevention

The best treatment for anal stenosis after hemorrhoidectomy is a meticulous approach in the operating room during the primary operation. The risk of anal stenosis increases with the complexity and extent of the hemorrhoids treated. Surgical therapy of extensive and complicated hemorrhoids should only be approached by surgeons experienced in this operation [23]. The keys to prevention of anal stenosis after hemorrhoidectomy are meticulous submucosal dissection with avoidance of injury to the internal sphincter muscle and the preservation of sufficient intact anoderm between excision sites, generally considered at least 1 cm of intact intervening anoderm. Additionally, limiting the number of hemorrhoids excised in a given setting will also help to limit the incidence of postoperative stenosis.

Nonoperative Intervention

The cornerstone of therapy for anal stenosis from all causes is dietary modification, including a combination approach utilizing stool softeners as well as increased fiber intake and water consumption. For many patients with mild stenosis, these simple measures may alleviate the patient’s symptoms. For patients not initially responsive to these measures, and those with moderate stenoses, it is reasonable to attempt a course of manual dilation in addition to the above measures. This program consists of an initial dilation in the operating room or clinic, if tolerated, followed by serial dilations at home by the patient using either a finger or a dilator (Fig. 44.2). This can be facilitated and better tolerated through the use of anesthetic jelly (e.g., lidocaine 2 %). The majority of patients with mild stenosis will achieve symptom alleviation with this approach, as will many patients with moderate stenosis [14, 17, 19, 24]. Manual dilation does have some risks, such as perforation, but these risks are low [25].

Fig. 44.2

An example of pediatric dilators ranging in size from 15 to 21 mm used for dilation of anal stricture

Operative Intervention

Operative therapy is usually reserved for patients with severe stenosis or those with moderate stenosis that have failed nonoperative therapy. Many different procedures have been described to treat anal stenosis; however, there are few comparative prospective studies to guide therapy. Different patient-specific issues may lend themselves to the use of different techniques (Table 44.2).

Table 44.2

Technique and setting of use for procedures for the treatment of anal stenosis

Technique | Setting |

|---|---|

Lateral internal sphincterotomy | Functional stenoses |

Mild low anatomic stenoses | |

Used in combination with advancement flap techniques in the treatment of some anatomic stenoses or combined stenoses | |

Lateral mucosal advancement flap (endorectal advancement flap) | High and some mid-anatomic stenoses |

Perianal skin advancement flaps (V-Y, Y-V, Diamond, House, U-shaped flaps) | Low and some mid-anatomic stenoses |

Anatomic Versus Functional Stenoses

True functional anal stenosis refers specifically to patients that have a defect in the relaxation of the sphincter complex. These patients do not have abnormalities of the anoderm. Patients with anatomic anal stenoses have a defect in the anoderm, which is not related to relaxation of the sphincter complex. A common situation is that patients will have a combined issue, meaning impaired sphincter complex relaxation as well as structural scarring. Differentiating true functional and anatomic stenosis may be apparent on physical examination; however, patients will often need further testing to ensure the appropriate diagnosis is obtained. As mentioned, patients with true functional stenoses will commonly show relaxation with the induction of anesthesia during EUA and will not have evidence of anoderm stricturing. Additionally, in the circumstance of a combined stenosis in patients with previous anorectal surgery, it is advisable to obtain preoperative anal manometry to help in guiding operative treatment. One of the most potentially devastating complications of the procedures to treat anal stenosis is loss of continence; therefore, any operation should be entered into with as much foreknowledge as possible to determine the best course of action.

Preoperative Planning

As noted, the diagnosis of anal stenosis is generally made by history and physical examination. Anoscopy, rigid proctoscopy, and colonoscopy should be used selectively on a case-by-case basis. It is recommended that patients undergo bowel preparation based on surgeon preference, although this may be difficult for patients with more severe stenoses. There are no data to support the use of preoperative antibiotic regimens, especially for more minor procedures; however, we frequently use intravenous ciprofloxacin and metronidazole or ertapenem for more extensive procedures unless there is a concern indicating usage of broader preoperative antibiotic coverage. The patient is brought to the operating room and placed in the prone jackknife position. Depending on the choice of anesthetic, patients should be intubated under general anesthetic prior to positioning. Alternatively, if local anesthetic is chosen, the patient may move over to the bed independently. The buttocks are taped apart to provide further exposure to the perianal area. The patient is then prepped and draped in the standard fashion based on surgeon preference. After the patient is sufficiently relaxed, local anesthetic is infiltrated. Local anesthetic can be considered even under general anesthesia both for better differentiation of functional stenosis and for postoperative pain relief.

Lateral Internal Sphincterotomy

For patients with primarily functional stenoses or mild mid- to low-anatomic stenoses, symptom relief may be achieved with internal sphincterotomy alone. This may be accomplished by single [24] or multiple internal anal sphincterotomies [18], to include bilateral internal anal sphincterotomy [26] in some cases. Good results have been reported with sphincterotomy in the case of mild- to moderate-low anal stenoses, as well as some mid- or high stenoses, with most patients being able to be managed in this way [18]. If the patient does not have sufficient normal anoderm, however, initial relief of symptoms may occur, but post-procedural scarring may lead to recurrent anatomic stenosis. To help diminish this issue, the wound is left open to heal by secondary intention and patients are maintained on an aggressive post-procedural regimen of stool bulking agents, laxatives, and increased hydration [20]. An important consideration when considering sphincterotomy is the possibility of postoperative fecal incontinence. This issue generally resolves with time and is worse with flatus than stool, but can be devastating if it persists. Depending on the individual case, it may be prudent to obtain preoperative anal manometry to determine the patients’ sphincter function prior to considering this approach. It is a rare circumstance where the authors would favor this approach to stenosis after hemorrhoidectomy.

Lateral Mucosal Advancement Flap

The most common procedure used for proximal anatomic anal stenosis is a lateral mucosal or endorectal advancement flap (Fig. 44.3) [27]. This procedure is initiated by making a lateral incision in the perianal skin and transition zone such that the scar is completely divided (and a lateral internal sphincterotomy may also be performed simultaneously, if favored by the surgeon). Following scar division, the rectal mucosa is then mobilized proximally in a triangular or tongue-like formation proximally into the distant rectum in the muscular plane for 4–6 cm, ensuring that the flap can easily reach to interpose across the scar/stenosis with little to no tension. While this flap is referred to as a mucosal flap, it is vitally important to include mucosa, submucosa, and a portion of the circular muscle of the rectal wall, as flaps including only the mucosa and submucosa are prone to developing recurrent stricture due to ischemia. Additionally, the width of the flap base (proximal) should be approximately twice the width of the apex (distal) as another method to ensure adequate blood supply. The flap is then sutured to the anoderm distal to the stenosis using absorbable sutures in an interrupted, full-thickness fashion (the authors favor 3-0 vicryl, or more rarely, 3-0 chromic for smaller flaps). It is important that the mucosal flap is not fixed distal to this point, as this may lead to ectropion formation. Any portion of the excision of the stricture external to the intersphincteric groove should be left open to heal by secondary intent to avoid ectropion formation and minimize the risk of recurrent stricture. This procedure is generally well tolerated by patients in terms of postoperative pain with good long-term outcomes, and the procedure may be able to be performed with sedation and local anesthesia [21, 27, 28]. While this method is useful for proximal stenoses, perianal skin advancement flaps are better techniques for more distal anatomic stenoses.

Fig. 44.3

Perianal flap techniques for anal stenosis. a Y-V flap. b V-Y flap. c Diamond flap. d House flap. e rotational S-flap (With permission from [40] © Springer)

Y-V Advancement Flap

One widely performed procedure is the Y-V advancement flap, especially for low and mid-stenoses. The Y-V advancement flap is accomplished by making a wide-based V-shaped incision with the apex just distal to the stenosis and the base of the flap laterally on the anoderm and perianal skin at least 2–3-cm wide, after which the “Y” extension is made from the apex of the “V” through the entire length of the area of stenosis (Fig. 44.3). The flap is then mobilized by dividing the deeper subcutaneous attachments perpendicular to the skin while taking care to ensure both preservation of the subdermal blood supply and a tension-free repair, commonly requiring mobilization to the level of the underlying fascia depending on flap location. The apex of the V is then sutured to the distal corner created by the Y extension at the level of the internal-most aspect of the stenosis using interrupted longer term absorbable sutures (for example, 4-0 or 3-0 Monocryl or PDS), which creates the final “V” configuration of the repair. This technique has been described as very effective for relieving patients’ symptoms [29–31]. The procedure can be performed in the posterior or lateral positions, and bilaterally, if necessary [20].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree