Altemeier

Dana R. Sands

The optimal treatment of rectal prolapse has been debated for centuries. Numerous abdominal and perineal procedures have been described in the literature, which lead us to conclude that the “best” repair is one that is tailored to the individual patient. Many considerations are necessary to determine the correct approach, the most obvious being the patients’ age and any coexistent comorbidities. Perineal approaches are invaluable for management of this problem in the elderly population.

Perineal approaches have traditionally been associated with higher recurrence rates, yet some of the more recently reported recurrence rates have been comparable to abdominal approaches (1,2,3), with the overall impression that this improvement is attributable to the addition of a levatoroplasty (4,5,6,7). Since the incidence of rectal prolapse is at its highest in the fifth, sixth, and seventh decades of life, the drawback of a higher recurrence rate is balanced by the reduction in perioperative morbidity. It is therefore necessary to appropriately counsel patients regarding a higher likelihood of recurrence, such as those undergoing a perineal procedure as a primary or repeat operation for the treatment of prolapse (4,8,9,10,11,12).

Perineal Rectosigmoidectomy

First described by Mikulicz in 1889 (13), the perineal rectosigmoidectomy was subsequently advocated by Miles in 1933 (14). It was ultimately championed in the United States by Altemeier and Culbertson in the late 1960s, early 1970s and therefore now bears the eponymous name of Altemeier (15,16,17).

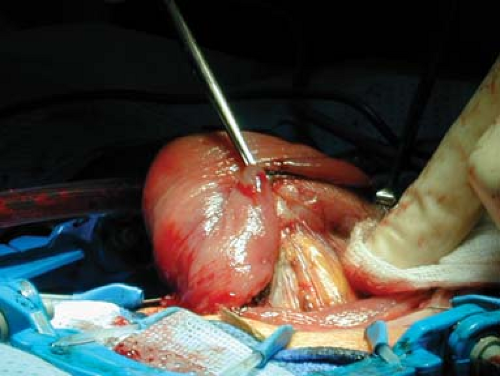

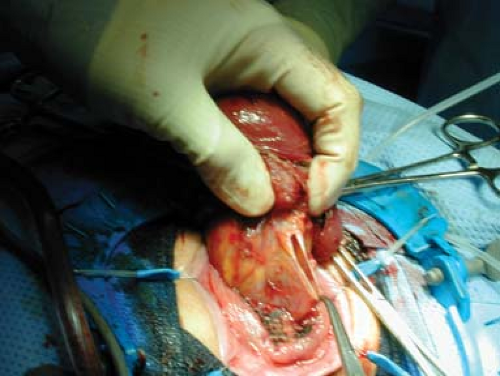

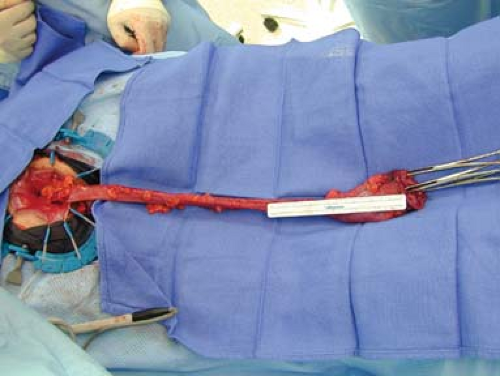

Traditionally, the Altemeier procedure involves a full thickness resection of the rectum, starting 1 cm proximal to the dentate line and can often include resection up to the sigmoid colon. The bowel is first everted and the prolapse is reproduced (Fig. 16.1). Following this maneuver, a full thickness incision is made 1–2 cm proximal to the dentate line (Fig. 16.2). Proximal dissection is undertaken until the peritoneal hernia sac is identified and opened (Fig. 16.3). This step is crucial in allowing the surgeon to assess the amount of sigmoid redundancy. The mesentery is sequentially divided until there is no further redundancy noted. This process is greatly expedited with the newer vessel sealing devices. Once all of the redundant bowel has been removed, the prolapse is amputated (Fig. 16.4). An anterior levatoroplasty can be performed at this point. The anastomosis is then performed (Fig. 16.5).

Perineal rectosigmoidectomy is the operation of choice for patients with an incarcerated, gangrenous rectal prolapse. In male patients, one of the most important complications has been sexual dysfunction secondary to extensive pelvic dissection and posterior rectopexy procedures, leading some surgeons to a recommend a perineal approach for young male patients (11,18).

Table 16.1 lists patients undergoing perineal rectosigmoidectomy with reported mortality rates of 0–5% and recurrence rates from 0 to 16%. One of the most important modifications to the perineal rectosigmoidectomy has been the addition of the levatoroplasty which will be addressed separately. Data listed include studies where an additional levatoroplasty was employed and those where it was not (1,2,3,4,6,7,8,11,17,19,20,21,22,23,24).

Table 16.1 Results of Perineal Rectosigmoidectomy for Rectal Prolapse | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|