Chapter 40 ALCOHOLIC LIVER DISEASE

PATHOLOGY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Symptoms and signs are not reliable indicators of the presence or severity of ALD. There may be no symptoms even in the presence of cirrhosis. In other cases, clinical features do allow a confident diagnosis. The clinical and pathological spectrum of alcoholic liver disease includes fatty liver, hepatitis and cirrhosis, but these commonly coexist.

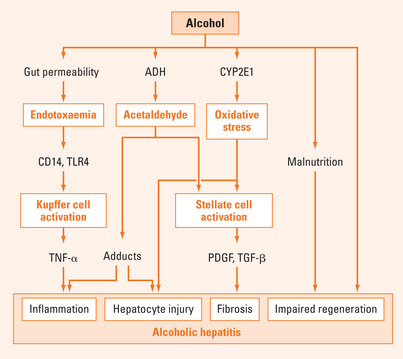

Alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic hepatitis is defined pathologically by polymorphonuclear infiltration with hepatocyte injury (ballooning necrosis and apoptosis), accumulation of Mallory’s hyaline (derived from intermediate filaments) and variable hepatic fibrosis. It presents with anorexia, nausea and abdominal pain, with jaundice, bruising and encephalopathy in association with alcohol abuse. Hepatomegaly may be marked and associated with tenderness, splenomegaly, signs of liver failure and ascites. Systemic disturbances include fever and neutrophilic leucocytosis. The gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) is the predominant abnormality. The AST generally exceeds the ALT, but both are only moderately raised. Values for aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) above 500 U/L suggest another disorder that may coexist with ALD, most often viral hepatitis or paracetamol (acetaminophen) toxicity.

Mild cases are common and typically manifest with abnormal serum biochemistry, and hepatomegaly. Severe alcoholic hepatitis is relatively rare and carries a short-term mortality of approximately 50%. The severity of alcoholic hepatitis can be assessed using a number of simple quantitative indices (Maddrey score, MELD Score, Combined Clinical and Laboratory Index). Of these, the Maddrey Discriminant Function (MDF) is the simplest (Table 40.1).

TABLE 40.1 Using the Maddrey score to assess the severity of alcoholic hepatitis

Alcoholic cirrhosis

Alcoholic cirrhosis may present with fatigue, anorexia, nausea, malaise or weight loss but typically presents with complications such as portal hypertension leading to variceal bleeding and/or ascites, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma. Alcoholic cirrhosis is a recognised risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma but it is not clear that there is an association between alcohol abuse and hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis.

DETECTION OF ALCOHOL ABUSE

Several brief questionnaires have been validated for the detection of alcohol abuse (Table 40.2). If a screening test is positive, more detailed assessment is indicated.

TABLE 40.2 Screening questions for excessive alcohol consumption

| A positive response on screening indicates the need for further assesssment |

Laboratory markers such as gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) are only moderately sensitive and specific for drinking problems in general. In ALD, the GGT level is almost invariably elevated. However, elevated levels may also be seen in other liver diseases and with some drugs (notably anticonvulsants). The MCV is generally less sensitive and less specific than GGT. Combined assessment of MCV and GGT detects 70% of the alcohol-dependent population. The carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) test may be more specific than GGT, but the test is not widely available at present and there are false positives in any form of advanced liver disease. Several other laboratory parameters may be elevated, including uric acid, triglycerides and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. These are not adequately sensitive or specific for use as a screening test.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree