Fig. 14.1

Afferent loop obstruction in a 62-year-old man after Roux-en-Y gastroenterotomy. a Axial plane of MDCT shows a dilated fluid-filled afferent loop ( arrow) located at the mid-abdomen and crossing between the aorta and superior mesenteric artery. b Coronal plane of MDCT reveals the configuration of the afferent loop to be of a “C” character. c Keyboard sign ( arrows) is also clearly demonstrated. Focal bowel thickening at the anastomotic region is present, suggesting local recurrence. Endoscopic biopsy confirmed the MDCT diagnosis of local recurrence. (With permission from [28] © Copyright: Yonsei University College of Medicine 2011; Creative Commons Public License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/legalcode . Used without modification)

In patients with ALS, abdominal ultrasound may reveal a fluid-filled mass in the right upper quadrant or a peripancreatic cystic mass. Derchi et al. identified the distended afferent limb as a fluid-filled structure in four patients with ALS caused by tumor recurrence at or near a Billroth II gastrojejunostomy [29]. Lee et al. reported similar findings in a study of seven ALS patients, observing the obstructed afferent limb as a dilated, fluid-filled structure crossing the midline in the upper abdomen [30].

In patients in whom ultrasound and endoscopy are nondiagnostic, hepatobiliary scintigraphy may prove useful in diagnosing chronic ALS. Sivelli et al. used technetium-99 m hepatoaminodiacetic acid scanning in 50 patients and found that hepatobiliary scanning is useful in diagnosing ALS [31]. Despite other studies showing success using mebrofenin and hepatoaminodiacetic acid scanning [17, 32], scintigraphic studies should be reserved for cases where abdominal CT and ultrasound are nondiagnostic.

Invasive studies such as esophagogastroduodenoscopy allow for direct visualization of the gastrojejunostomy and detection of possible modes of obstruction (i.e., volvulus, herniation, ulceration, etc.). In addition to identifying possible masses in the region of the gastrojejunostomy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy can be helpful in distinguishing between alkaline reflux gastritis and ALS [10].

Treatment

Medical Treatment

Acute ALS requires immediate diagnosis and corrective surgery. Indeed, the major pitfall associated with ALS is a delay in diagnosis due to risk of intestinal perforation and sepsis [33]. Patients with chronic ALS may develop malnutrition or anemia [22, 34], and may derive benefit from nutritional therapy or transfusion prior to surgery.

Endoscopic/Interventional Radiology

Although surgical conversions have been the treatment of choice, percutaneous tube drainage or stent placement has been performed as a palliative treatment for patients who cannot tolerate a surgical procedure. Metallic stents have been used for the relief of afferent loop syndrome due to number of etiologies [35–37]. In a 77-year-old patient with afferent loop obstruction due to recurrent cancer, a double-pigtail catheter placed beyond the ampulla of Vater resolved symptoms [36]. Two cases of refractory ALS were successfully treated by transhepatic biliary catheterization coupled with transcholecystic cholangiography, both showed clinical improvement with no complications [37]. More recently, Lee et al. described the successful endoscopic treatment of near-complete obstruction of the efferent loop with insertion of a double-pigtail stent (Fig. 14.2a–e) [38]. A study by Morita and colleagues indicated that percutaneous transhepatic catheter drainage for obstructed afferent loop may be risky due to the development of septic shock [39]. In such cases, the authors suggested an additional drainage catheter of the bile duct might be needed when biliary stasis is present.

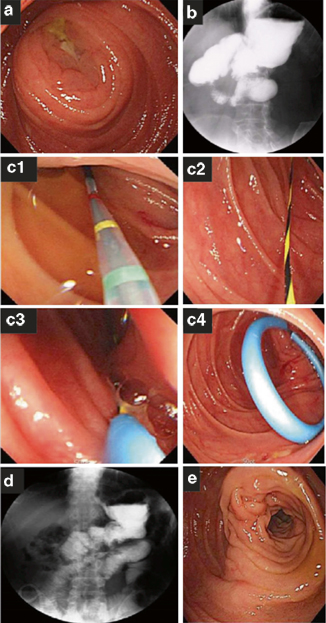

Fig. 14.2

Endoscopic finding revealed a narrowed and swollen entrance of the efferent loop (a). Gastrografin study showed nearly complete obstruction of the efferent loop (b). Endoscopic stent procedure was performed that double-pigtail stent was inserted through efferent loop stenosis and over the guide wire using double-channel endoscope under endoscopic view (c). Follow-up gastrografin and endoscopic study showed free flow of contrast and recovery of narrowed, swollen orifice of the efferent loop (d, e). (With permission from [38] Baishideng Publishing Group Co., Limited)

Han retrospectively analyzed the clinical effectiveness of placement of dual stents in 13 consecutive patients who underwent operations for gastric cancer, cholangiocarcioma, or pancreatic adenocarcinoma and subsequently developed afferent loop syndrome due to disease progression. Twelve of the 13 patients experienced normalization of their abnormal biliary laboratory findings and decompression of the dilated bowel loop following dual stent placement [40].

Kim et al. found that percutaneous tube enterostomy is an effective palliative treatment in ALS presenting as obstructive jaundice [41]. Radiographically guided interventional techniques with metallic stents have been used to effectively palliate ALS caused by a number of different etiologies. Successful palliation of biliary obstruction was achieved using transhepatic metallic stents across duodenal and biliary strictures for the treatment of malignant ALS caused by inoperable carcinoma of the head of the pancreas [35]. Percutaneous transhepatic metallic stent insertion for malignant afferent loop obstruction following pancreaticoduodenectomy for carcinoma of the ampulla of Vater is an option [42]. Percutaneous transhepatic insertion of metal stents was also successfully used to treat ALS due to distal gastrectomy [36]. A study by Song et al. looked at the use of metallic stents in 39 patients with recurrent cancer after gastrojejunostomy and found that placement of expandable metallic stents was successful in 90 % of patients, but did require accurate knowledge of surgical procedure and tumor recurrence pattern for effective stent placement [43].

Surgical Intervention

Surgical treatment of chronic ALS, unlike acute ALS, is an elective procedure. Surgical interventions ranging from simple operations to major resections have been used to effectively treat afferent loop obstruction. In some cases, suture fixation to reduce angulations and kinks have been reported to successfully alleviate afferent loop obstruction [44]. In a study of 79 patients in 1951, Capper and Butler recommended suspension of the afferent jejunal loop to the posterior peritoneum and hepatic omentum to promote drainage of the efferent loop [45].

The most widely used procedure for the surgical correction of ALS involves deconstruction of the Billroth II gastrojejunostomy followed by restoration of gastrointestinal continuity with a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy (Fig. 14.3a–c).

Fig. 14.3

Afferent loop syndrome ( ALS) is caused by mechanical obstruction of the afferent loop of a double-barrel gastrojejunostomy (a). ALS may be surgically corrected by deconstructing the Billroth II gastrojejunostomy and restoring gastrointestinal continuity with a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy (b). Alternatively, entero-anastomosis between the afferent and efferent loops may be performed to bypass the obstruction (c)

Theodor Billroth performed the first gastroduodenostomy in 1881 following partial gastrectomy on a patient with carcinoma of the stomach [46]. A Bilroth I gastroduodenostomy creates an anastomosis between duodenum and stomach. However, the use of this procedure should be avoided in patients with duodenal scarring or previous subtotal gastrectomy due to the risk of excessive tension on the anastomosis. Gastroduodenostomy itself can cause ALS, among other postgastrectomy syndromes, and for this reason the technique of Roux-en-Y anastomosis was developed by Wolfer in 1883. Cesar Roux of Lausanne later popularized the procedure in 1887 [47].

The Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy involves dividing the jejunum distal to the ligament of Treitz and anastomosis of the stomach to the proximal portion of the distal jejunal segment. The distal proximal jejunal segment is anastomosed to the distal end of the Roux limb [47]. Possible complications of the Roux-en-Y gastroejejunostomy include proximal blind loop, duodenal stump blowout, and bile reflux gastritis [48]. A variant of this operation, termed the “uncut” Roux-en-Y gastroejejunostomy, involves occlusion via stapling rather than complete division of the jejunum and is intended to avoid Roux stasis syndrome [49]. However, risk of staple line dehiscence stands in the way of widespread adoption of this procedure.

Alternatively, resection of the redundant segment of the afferent jejunal loop, entero-anastomosis (Fig. 14.3c), or revision of the gastrojejunostomy may be performed. Entero-anastomoses between afferent and efferent loops are complicated by possible marginal ulceration and should be avoided unless vagotomy or gastric resection is performed.

Summary

Although ALS is a rare complication following gastric surgery, early diagnosis and treatment of the obstruction are critical given the risk of bowel perforation and subsequent sepsis. In the case of chronic manifestations of the syndrome, proper treatment is dependent upon a thorough understanding of patient-specific etiology, anatomy, and associated complications.

Key Points for Avoiding

1.

Avoid Billroth II gastrojejunostomy whenever possible

2.

Make an afferent limb shorter than 30–40 cm

3.

Avoid an antecolic anastomosis to the gastric remnant

4.

Close mesocolic defects following gastrojejunostomy

5.

Early diagnosis is critical to avoiding intestinal perforation and sepsis

Key Points for Diagnosing/Managing

1.

Physical exam and laboratory findings are generally nonspecific

2.

Abdominal CT is the noninvasive imaging study of choice in the diagnosis

3.

Upper endoscopy allows for direct visualization of the anastomosis and obstruction

4.

Surgical correction of the mechanical obstruction is the most common management

5.

Percutaneous drainage or endoscopic stent placement may also be performed in patients who cannot tolerate an operation.

References

1.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree