When cavernous hemangiomas are greater than 8 cm in diameter, they are called giant cavernous hemangiomas. Their histologic findings are similar to that of smaller hemangiomas, but they are more likely (in about 40% of cases) to have an ill-defined border of vascular proliferation in the adjacent parenchyma (eFig. 19.3). This finding is called hemangiomatosis or hemangioma-like vessels and is characterized by small scattered aggregates of dilated and somewhat telangiectatic-appearing vessels that can be smaller in size than those in the main lesion.1,2 Similar findings can be found very focally in smaller hemangiomas also.

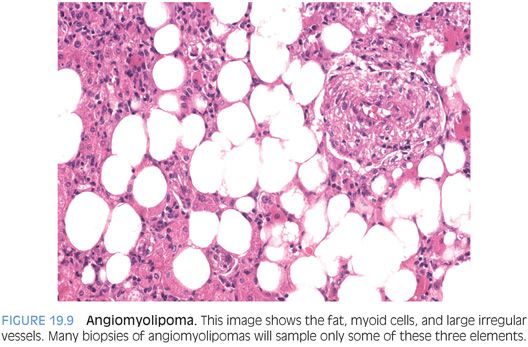

A rare variant of liver hemangiomas is the capillary hemangioma,3 also called a lobular hemangioma at times. Capillary hemangiomas have a modest female predominance and a wide range of reported ages. A possible predilection for Asian ethnicity has also been suggested.4 This tumor is composed of small thin-walled vessels, often growing in a lobular arrangement (Fig. 19.2). The tumors can be single or rarely multiple. The vascular lumens can be inconspicuous in some areas, leading to a more solid appearance. However, occasional larger caliber vessels can be present both at the periphery and center of the tumor. Some of the large caliber vessels can show myxoid change in their walls. Cytologically, the tumor cells are plump but without atypia or mitotic activity. Extramedullary hematopoiesis may also be present. Immunostains for vascular differentiation, such as CD34 (eFig. 19.4) or ERG can be helpful.

EPITHELIOID HEMANGIOENDOTHELIOMA

Definition

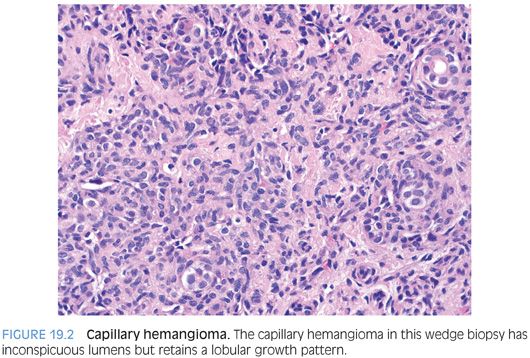

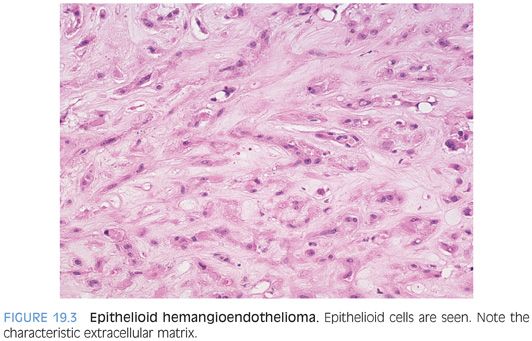

Epithelioid hemangioendotheliomas (EHEs) are low-grade malignant vascular tumors composed of epithelioid and dendritic tumor cells embedded in a myxoid or hyalinized stroma.

Clinical Findings

The average age at presentation is 47 years, but the highest tumor incidence is between the ages of 30 and 40 years.5 There is a slight female predominance.5 The presenting symptoms are generally mild with vague abdominal pain, although weight loss and jaundice can also be seen. A large proportion of tumors, approximately 40%, are incidental findings.

Histologic Findings

EHEs are multifocal and involve both lobes of the liver in more than 80% of cases. The tumors range in size from subcentimeter to 14 cm. They arise in noncirrhotic livers. However, vascular spread can lead to marked atrophy and regeneration of the liver that can mimic cirrhosis. Microscopically, the tumors are generally of moderate cellularity, but the tumor cellularity can vary from marked to sparse. In all cases, the neoplastic cells are embedded in extracellular matrix. The extracellular matrix is quite distinctive and is often the first clue to the diagnosis. The extracellular matrix is often loose and amphophilic but can also have a more hyalinized and eosinophilic appearance. In general, tumor cellularity tends to be denser at the periphery and sparser in the center of the tumor, which can even become densely sclerotic. The sclerotic areas can have calcifications. Some tumors may show areas of necrosis and hemorrhage.

Cytologically, the tumor cells can have an epithelioid appearance with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 19.3, eFig. 19.5). Cells with a dendritic appearance are also seen (the dendritic nature is further enhanced on immunostains). The epithelioid cells are eosinophilic and have moderate amounts of cytoplasm, vacuolated nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli. In almost all cases, especially with a large biopsy or full resection, some of the epithelioid cells will have a signet ring cell–like morphology (Fig. 19.4, eFig. 19.6), occasionally with red blood cells in the lumen. The signet ring–like cells are mucicarmine-negative. Mitotic figures tend to be absent or rare. In some cases, focal areas of better formed vessels may be present (eFig. 19.7).

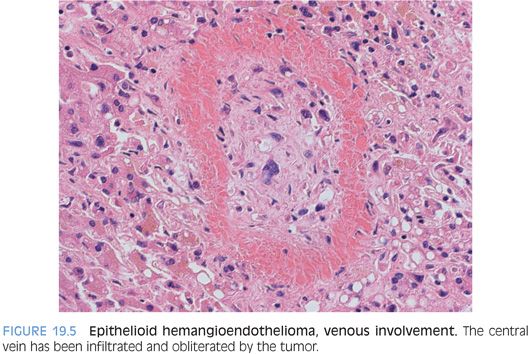

EHEs typically have an infiltrative growth pattern and can grow along the sinusoids, causing atrophy or dropout of the hepatocytes. Entrapped portal tracts are common at the periphery. The portal veins and the central veins are often involved by tumor. The most common pattern of vascular involvement is fibro-obliteration of the veins, with tumor cells within a fibrotic matrix (Fig. 19.5). However, the tumor can also grow as small polypoid nodules of tumor cells within an otherwise non-obliterative vascular lumen. Hepatic arteries can also be involved, but this is less common. The tumor will involve the liver capsule in about half of cases. Most tumors will have minimal to mild inflammation. The inflammation is most commonly lymphocytic but rarely can be neutrophil-rich. In a few cases, there can be marked inflammation. Of the various histologic findings, marked tumor cellularity has the strongest predictive ability for aggressive behavior, but all EHEs are malignant and have the potential for aggressive behavior.

A large series of cases from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) noted that a very high proportion of EHE were submitted with a wrong preliminary diagnosis.5 The most common misdiagnosis was cholangiocarcinoma, presumably because the tumors can have signet ring–type cells and abundant extracellular matrix. Other common misdiagnoses were angiosarcoma and other carcinomas, including both hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic carcinomas. Overall, the distinctive extracellular matrix and the distinctive cell types (dendritic, signet ring–like) will provide strong clues to the diagnosis in essentially all cases, a diagnosis which can then be confirmed by immunostains.

Immunostains

Immunostains are helpful in confirming the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) impression. Reported rates of positivity in the largest series to date are as follows5: factor VIII (99%), CD34 (94%), CD31 (86%), and factor XIIIa (100%, but only six cases were stained). Smooth muscle actin is positive in 26% and cytokeratin AE1/3 in 14%. Also of note, CD10 is positive in most EHEs,6 which can sometimes be confusing if the biopsy is small and the distinctive H&E findings not well represented. In general, the epithelioid areas stain better with vascular markers than the dendritic areas.

ERG is a recently reported immunostain that is a very sensitive marker for endothelial differentiation. ERG was positive in 42 out of 43 EHEs.7 ERG also stains about 30% to 50% of prostate cancers, a subset of meningiomas, and rare Ewing sarcomas and mesotheliomas.7,8 Blastic extramedullary myeloid tumors are also ERG-positive in most cases. However, when combined with morphology and other stains, ERG is a very useful stain for identifying vascular differentiation.

ANGIOSARCOMA

Definition

Angiosarcoma is a high-grade malignant vascular tumor that can have a variety of growth patterns.

Clinical Findings

Angiosarcomas of the liver can be a challenge on liver biopsy because they are rare and because they often mimic other tumors. Angiosarcomas can be primary to the liver or metastatic. Recognized risk factors for primary angiosarcomas include arsenic (found in the groundwater in some parts of the world), androgen therapy, Thorotrast, and vinyl chloride exposure. However, no cause is identified in 70% of cases. Most affected individuals are older men. The prognosis is dismal with few individuals surviving more than 6 months.

Histologic Findings

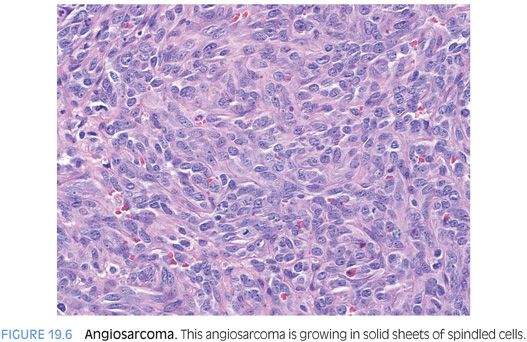

Angiosarcoma can be a single mass or multiple tumors. The background liver findings can show chronic inflammation or fatty change, and fibrosis can range from none to cirrhosis. Histologically, angiosarcomas can grow as clearly vascular tumors with irregular blood vessels (eFig. 19.8) or as solid epithelioid tumors that mimic carcinomas or spindle cell tumors that mimic other sarcomas (Fig. 19.6, eFig. 19.9). An important histologic clue can be the presence of rare small slit-like spaces with red blood cells. The tumor cells typically show significant atypia and numerous mitotic figures. In some cases, the solid areas can undergo necrosis and cavitation, leaving only a rim of malignant cells surrounding a cavity filled with blood, fibrin, and necrotic debris.

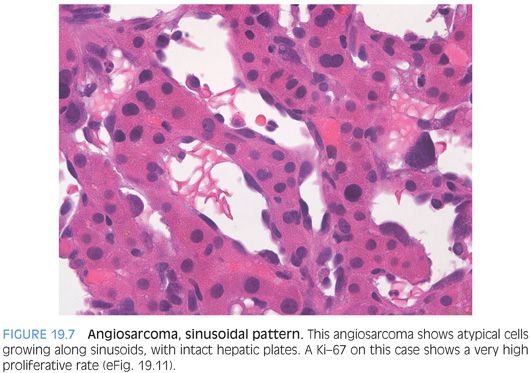

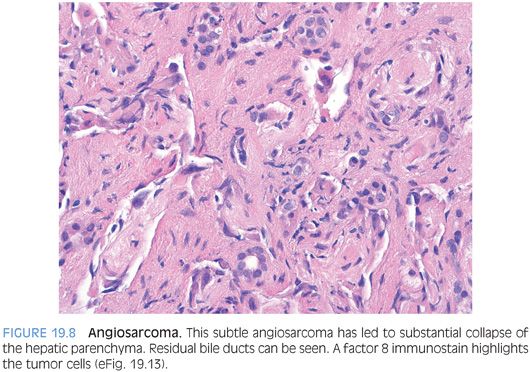

As another important but subtle growth pattern, some angiosarcomas extend along the sinusoids, replacing the normal benign sinusoidal endothelial cells but leaving the hepatic plates relatively intact (Fig. 19.7, eFig. 19.10). This pattern can be diagnostically challenging on biopsy, depending on the amount of sampled tumor. A Ki-67 can be helpful in demonstrating a very high proliferate rate (eFig. 19.11). The sinusoidal growth pattern is almost always present in some part of the tumor with fully resected specimens, but the growth patterns can vary considerably on biopsy specimens. Finally, some angiosarcomas with a sinusoidal infiltrative growth pattern can cause complete or near complete loss of hepatocytes and the biopsy may show parenchymal collapse and proliferating bile ducts. The atypical endothelial cells of the angiosarcoma can be easily overlooked (Fig. 19.8, eFig. 19.12) on H&E and often require immunostain to bring them out (eFig. 19.13).

Immunostains

Immunostains should be used to confirm the diagnosis. Although most of the published data are from angiosarcomas in soft tissues and not specifically from angiosarcomas of the liver,9 the data is still informative. Endothelial differentiation can be demonstrated by immunostains for factor VIII (positive in 80% to 90% of cases), CD34 (75%), and CD31 (30%). As noted in the section on EHEs, ERG is a new and sensitive immunostain for vascular differentiation that can be helpful when evaluating a case for possible angiosarcoma.

Aberrant cytokeratin AE1/3 positivity can be seen in about 45% of angiosarcomas and CAM5.2 in 30% of cases,9 so be aware of this important diagnostic pitfall.

ANGIOMYOLIPOMA

Definition

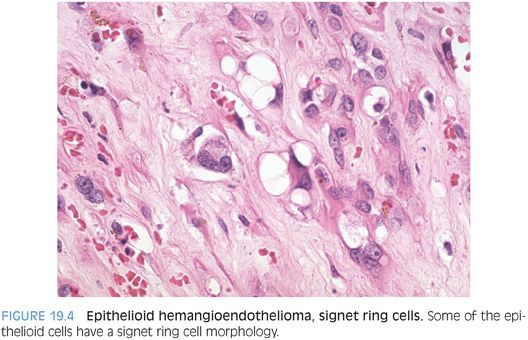

Angiomyolipoma is a benign mesenchymal tumor composed of myoid cells, typically admixed with fat and large irregular vessels.

Clinical Findings

Most angiomyolipomas of the liver (90%) are sporadic and not part of the tuberous sclerosis complex. In most cases (90%), a single tumor is present, but rare multifocal cases have been reported. The average age is 49 years, and there is a strong female predilection.10 The background liver is typically nondiseased and not fibrotic. They can be diagnostically challenging, with some authors indicating that a full half of cases are initially misdiagnosed.10

Histologic Findings

Angiomyolipomas are composed of admixed tumor cells showing fatty change, smooth muscle or “myoid” differentiation, and large thick-walled vessels (Fig. 19.9). The myoid component can be composed of spindle (Fig. 19.10) or epithelioid cells (Fig. 19.11). The proportion of each component can vary considerably. A subset of tumors is composed mostly of fat. These fatty angiomyolipomas can closely mimic lipomas or liposarcomas.10,11 In fat-predominant tumors, the best place to find myoid components to help make the diagnosis are around thick-walled vessels. Other angiomyolipomas are composed mostly of spindled myoid cells and can mimic smooth muscle tumors.12 In yet another subset, the epithelioid myoid cells are predominant. This variant can closely mimic hepatocellular carcinoma, with tumor cells showing abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and moderate nuclear atypia. They can even have a trabecular growth pattern that closely mimics hepatocellular carcinoma.10 In some cases, tumor pigment can provide a clue to the diagnosis (Fig. 19.12). In other epithelioid variants, the cytoplasm will have a clear appearance and engender the differential for clear cell tumors. In fully resected specimens, at least minor components of all elements (fatty, myoid, epithelioid) are commonly seen, but in biopsy specimens, one morphologic growth pattern can predominate, so a high index of suspicion is helpful.