ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

ESSENTIALS OF DIAGNOSIS

Patients with acute upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding can present with hematemesis, melena, or hematochezia.

Clinical guidelines are recommended to predict outcomes, including rebleeding, and mortality.

Stigmata of recent hemorrhage are endoscopic findings that predict outcome.

Endoscopy can provide the diagnosis, prognosis, and the potential for therapy.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Nonvariceal upper GI bleeding is a common reason for emergency department visits and admissions to the hospital. It has been estimated that upper GI bleeding is responsible for over 300,000 hospitalizations per year in the United States. An additional 100,000–150,000 patients per year develop upper GI bleeding during hospitalizations for other reasons.

The source of upper GI bleeding is by definition proximal to the ligament of Treitz. The natural history of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding is that approximately 80% of patients will stop bleeding spontaneously and in this group, no further urgent intervention will be needed. However, if a patient rebleeds, there is a 10-fold increased mortality rate.

The overall mortality rate is up to 14% for patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding, with recent studies showing in-hospital mortality rates in the United States of 2–3%. Mortality is typically due to factors other than GI bleeding and occurs primarily in patients who are older and use medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (and, more recently, antiplatelet agents such as clopidogrel and the new oral anticoagulants such as dabigatran).

Among patients on long-term, low-dose aspirin, the risk of overt GI bleeding is increased twofold compared to placebo with an annual incidence of major GI bleeding of 0.13%. Compared with aspirin alone, the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel causes a two- to threefold increase in the number of patients with major GI bleeding. Definite risk factors for bleeding in patients taking aspirin and clopidogrel are a history of peptic ulcers and prior GI bleeding, and likely risk factors are male gender, age more than 70, and Helicobacter pylori infection. The serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been implicated as a possible cause of GI bleeding. Recent data show an increased risk of GI bleeding with certain combinations of drugs. Concomitant use of NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, or low-dose aspirin and corticosteroid therapies increased the risk for upper GI bleeding (up to 12.8 times). Concomitant use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and low-dose aspirin with aldosterone antagonists such as Aldactone produce an increased risk for upper GI bleeding of up to 11 times. The combination of NSAIDs and SSRIs increased risk was 1.6.

Mortality among patients with upper GI bleeding is often due to cardiovascular complications and comorbidities, and not due to uncontrollable GI hemorrhage. In most patients who develop GI bleeding while on aspirin, the aspirin therapy should be restarted once the risk for cardiovascular complications outweighs the risk for bleeding.

[PubMed: 24937265]

[PubMed: 19949136]

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The clinical presentation of bleeding should be characterized. Hematemesis is overt bleeding with vomiting of fresh blood or clots. Melena refers to dark black and tarry-appearing stool, with a distinctive smell. The term “coffee grounds” describes gastric aspirates or vomitus that contains dark specks of old blood. Hematochezia is the passage of fresh blood or clots per rectum. Although bright red blood per rectum is usually indicative of a lower GI source, it may be seen in patients with brisk upper GI bleeding.

Concurrent with the initial evaluation of patients with suspected upper GI bleeding attention needs to be paid to resuscitation, with the goal of achieving hemodynamic stability. The evaluation must assess vital signs, the presence or absence of shock and hypovolemia, and medical comorbidities (malignancy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, coronary artery disease, etc). Patients with postural hypotension have a significant blood volume loss of at least 10% and those with shock have a blood volume loss of at least 20%, a predictor of poor outcome. Medications used by the patient need to be reviewed with special attention given to anticoagulants (heparin and warfarin), antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel), aspirin, the new oral anticoagulants (dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban), SSRIs, and NSAIDs.

Factors that predict a good or a poor prognosis in patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding can be used to appropriately triage and manage patients. The role of nasogastric tube aspiration is controversial and currently is not recommended as part of the routine initial assessment. Although, the nasogastric tube aspirate can provide useful information depending on its contents, results can be falsely negative; false negatives may occur in patients with bleeding from duodenal ulcers due to spasm of the pylorus and can occur in other conditions, including gastric ulcers and, rarely, esophageal varices (if the tube is positioned in a nondependent area of the stomach). However, patients often find it very uncomfortable and recent data suggest that the performance of nasogastric tube lavage does not alter patient outcomes. The 2012 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) practice guidelines state that nasogastric tube or orogastric lavage is not required in patients with upper GI bleeding for diagnosis, prognosis, visualization, or therapeutic effect.

In patients presenting with upper GI bleeding, several clinical prognostic factors have been shown to be helpful in predicting a poor outcome (Table 31–1). Patients who experience onset of GI bleeding as outpatients have a lower rate of mortality compared with those who are inpatients hospitalized for other reasons. Age greater than 60 is associated with an increased mortality. The mortality rate increases along with the number of patient comorbidities.

Age >60 Shock (systolic blood pressure <100 mm Hg); pulse >100 beats/min Malignancy or varices as bleeding source Onset in hospital Comorbid illness Active bleeding (hematemesis, bright red blood in nasogastric tube, or hematochezia) Recurrent bleeding Severe coagulopathy |

[PubMed: 25090451]

Clinical risk stratification scores have been developed to help optimize the management of patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. The aims of these guidelines are to identify low-risk patients who can be discharged either directly from the emergency department or at an early stage of hospitalization, and to identify high-risk patients who are at risk for bad outcomes and will need the most resources. Many clinical guidelines include both clinical data and information obtained at the time of endoscopy. These guidelines should be incorporated as part of routine clinical care to help direct triage decisions. Recent international consensus recommendations and the ACG guidelines on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding recommend the use of prognostic scales for the early risk stratification of patients into low- and high-risk categories for rebleeding and mortality.

The Rockall score is a scoring system derived in the United Kingdom used to predict rebleeding and mortality in patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. The Rockall scoring system assigns scores of zero to three to the factors of age, the presence of shock, comorbidity, diagnosis, and endoscopic stigmata (Table 31–2). A low-risk patient has a score of two or less, which accounted for 29.4% of patients. In this low-risk group, there was a 4.3% risk of rebleeding and 0.1% mortality. Patients with Rockall scores of three to five have intermediate rates of rebleeding and mortality (2.0–7.9%), whereas patients with a score of six or greater have a high rebleeding and mortality rate (15.1–39.1%).

A scoring system that only uses clinical information obtained at the time of presentation, and does not include endoscopic data is widely used and called the Glasgow-Blatchford score (GBS). The clinical information incorporated in this scoring system includes hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen, pulse, systolic blood pressure, presence of syncope, melena, liver disease, and heart failure (Table 31–3). This scoring system for upper GI bleeding is valuable because all the information is available at initial presentation, and it does not require endoscopic performance to calculate.

| Score/Variable | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | <60 | 70–79 | ≥80 | — |

| Shock | None | Tachycardia (P >100 beats/min; SBP >100 mm Hg) | Hypotension (P >100 beats/min; SBP >100 mm Hg) | — |

| Comorbidity | No major comorbidity | — | Congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, any major comorbidity | Renal or liver failure, metastatic cancer |

| Diagnosis | Mallory-Weiss tears, no stigmata of recent hemorrhage | All other diagnoses | Upper GI cancer | — |

| Major stigmata of recent hemorrhage | None or spot | — | Clot, vessel, or spurting | — |

| Variable | Points |

|---|---|

| Systolic Blood Pressure (mm Hg) | |

| 100–109 | 1 |

| 90–99 | 2 |

| <90 | 3 |

| Blood Urea Nitrogen (mg/dL) | |

| >18 and <22 | 2 |

| >22 and <28 | 3 |

| >28 and <70 | 4 |

| >70 | 6 |

| Hemoglobin for Men (g/dL) | |

| 12.0–12.9 | 1 |

| 10.0–11.9 | 3 |

| <10.0 | 6 |

| Hemoglobin for women (g/dL) | |

| 10.0–11.9 | 1 |

| <10.0 | 6 |

| Other markers at presentation | |

| Heart rate >100 beats/min | 1 |

| Melena | 1 |

| Syncope | 2 |

| Liver disease | 2 |

| Cardiac disease/failure | 2 |

A recently developed risk stratification score for upper GI bleeding in the United States also only uses information at the time of the initial presentation and is called the AIMS65 score. This score, which is highly predictive of mortality, uses an equal weighting of its five components: albumin <3.0 g/dL, international normalized ratio (INR) >1.5, mental status changes, systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, and age greater than 65. Patients at high risk have two or more of these risk factors present. The AIMS65 score has been directly compared to the GBS found to be superior to the GBS for predicting mortality but similar in predicting a composite end point that included rebleeding.

Although recent international consensus and ACG guidelines recommend incorporation of risk stratification scores as a standard for the care of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding, there has not been widespread adoption of some of these scores. In a national survey of trainee and attending gastroenterologists, internists, and emergency department physicians to assess the barriers impeding adoption of these recommendations, among all physicians, 53% had ever heard of and 30% had ever used an upper GI bleeding risk score. More gastroenterologists than nongastroenterologists had heard of and used a risk score. Barriers to implementation of risk scores vary by physician’s specialty and training status; non-GI physicians and trainees lack knowledge of GI bleeding risk scores, whereas attending GI physicians are more aware of these guidelines, but choose to not implement them due to perceived lack of utility (Figure 31–1).

Figure 31–1.

Algorithm for the management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. ER, emergency room; ICU, intensive care unit. (Adapted, with permission, from Eisen GM, Dominitz JA, Faigel DO, et al. American Society for Gastroenterology. Standards of Practice Committee. An annotated algorithmic approach to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001 Jun;53(7):853–858.)

[PubMed: 20083829]

[PubMed: 11073021]

[PubMed: 24518802]

[PubMed: 20598244]

[PubMed: 8675081]

[PubMed: 8609747]

TREATMENT OF UPPER GASTROINTESTINAL BLEEDING

Patients need to have at minimum two large-bore peripheral intravenous access catheters (at least 18 gauges). Crystalloid fluids (normal saline or lactated Ringer) should be initially administered to maintain an adequate blood pressure. Supplemental oxygen should be administered routinely. Patients who are not able to adequately protect their airways or patients with ongoing severe hematemesis and at increased risk for aspiration should be considered for elective endotracheal intubation.

Concurrent with the initial evaluation of patients with suspected upper GI bleeding is resuscitation, with the goal of achieving hemodynamic stability. Blood transfusions in general should target hemoglobin >7 g/dL. The most direct evidence favoring a restrictive transfusion strategy comes from a randomized trial published that included 921 adults with acute upper GI bleeding. The patients were randomly assigned to receive transfusions if the hemoglobin was <9 g/dL (liberal transfusion arm) or to receive transfusions only if the hemoglobin was <7 g/dL (restrictive transfusion arm). Patients in the restrictive transfusion arm had lower mortality rates than those in the liberal transfusion arm (5% vs 9%; adjusted hazard ratio 0.55, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.33–0.92), supporting the use of a more restrictive approach to transfusion. However, in patients with clinical evidence of intravascular volume depletion, hemodynamic instability or comorbidities such as active cardiovascular or neurologic disease, a higher hemoglobin level may need to be targeted.

In patients with a coagulopathy, the coagulopathy should be corrected to an INR <2.5 if possible with transfusion of fresh frozen plasma or administration of vitamin K. In patients with a low platelet count (<50,000), platelet transfusion should be considered.

Various medications have been used to treat patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding, including antacids, histamine-2 (H2)-receptor antagonists, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and octreotide. The use of antacids and H2-receptor antagonists have not been shown to alter the natural history of patients with acute upper GI bleeding and are not recommended.

A. Proton pump inhibitors—In studies of PPIs in selected patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding, a benefit of medical treatment has been demonstrated. PPIs are the only drugs that can maintain a gastric pH of greater than 6.0 and can thus prevent fibrinolysis of an ulcer clot. The use of PPIs in the treatment of patients with upper GI bleeding has been widely adopted.

An improvement in outcomes with the use of PPIs in nonvariceal upper GI bleeding was first demonstrated by Khuroo and colleagues in a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral omeprazole (40 mg twice daily) versus placebo. Patients enrolled were a select group of 220 patients with peptic ulcers at endoscopy shown to have active bleeding, nonbleeding visible vessels, or adherent clots. Unlike the standard of care in most parts of the world, endoscopic therapy was not performed in this study. Outcomes were further bleeding, surgery, and death. There was a significant advantage to oral omeprazole use in patients who had findings of a visible vessel or an adherent clot. However, there was no advantage to prevent further bleeding in patients who had spurting or oozing lesions. This study, however, did not address whether patients who underwent therapy with endoscopic treatment at the time of endoscopy would attain additional benefit with the use of PPIs.

There have now been several studies showing the benefits of the use of PPIs in patients who have undergone endoscopic therapy with successful hemostasis. Lau and colleagues studied patients who had successful hemostasis using combination therapy of epinephrine injection and application of a bipolar cautery probe. Patients were then randomized to a bolus infusion of omeprazole, 80 mg, followed by a continuous infusion of 8 mg/h, versus a placebo infusion. In these patients, who had all undergone successful endoscopic therapy, the use of omeprazole reduced the rebleeding rates overall and the rebleeding rate within 3 days. There also was a trend toward reduction in surgery and death rates. Thus, with omeprazole use, bleeding is reduced in patients who have undergone endoscopic therapy and receive high-dose PPIs relative to those who undergo endoscopic therapy alone.

Additional studies have been performed that support combined endoscopic and medical management in select patients with upper GI bleeding. Sung and colleagues studied 158 patients with nonvisible vessels or adherent clots receiving omeprazole infusions, randomized to endoscopic therapy, or sham therapy. Patients who received both omeprazole infusions and endoscopic therapy had a lower median transfusion rate, less recurrent bleeding, and a trend toward decreased mortality.

In patients initially treated in the emergency department with a bolus infusion of omeprazole followed by a continuous infusion, the need for endoscopic therapy has been shown to be reduced. With the use of initial high-dose PPIs, the number of patients with actively bleeding lesions found at endoscopy is reduced and the number of patients with clean-based ulcers at the time of endoscopy is increased. Thus the early use of PPIs may result in a shift of lesions from high to low risk for further bleeding. However, the natural history of peptic ulcers treated with endoscopic therapies shows that it typically takes 72 hours for most high-risk lesions to become low-risk lesions.

At the present time, there are no studies that compare PPIs to one another in the management of acute upper GI bleeding. The available data suggest that the benefit is a class effect and that dosing should be similar, using the available intravenous PPIs. Although current guidelines recommend an 80-mg bolus followed by an 8 mg/h infusion for 72 hours in patients who have received successful endoscopic therapy, a 2014 study finds similar outcomes with intermittent bolus use of an intravenous PPI. In this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials, high-dose intravenous PPI administration did not have better outcomes when compared with intermittent dosing. Thus twice-daily dosing of a PPI is now recommended such as omeprazole 40 mg intravenously twice daily. A reasonable alternative is oral formulations if IV formulations are not available. Pantoprazole and esomeprazole are the only intravenous formulations currently available in the United States. Patients who remain stable may then be switched to a once-daily standard dose of oral PPIs (unless bleeding was due to severe esophagitis or complicated ulcer disease).

B. Octreotide—Octreotide can be used to treat patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. Although this medication is widely used in patients with variceal bleeding, there is evidence that it may also be helpful in patients with nonvariceal bleeding. In a meta-analysis by Imperiale and Birgisson, 1829 patients from 14 trials using octreotide or somatostatin in nonvariceal upper GI bleeding had a relative risk for further bleeding of 0.53 (0.43–0.63), suggesting that octreotide reduces the risk for continued bleeding from nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. Although a useful adjunctive treatment, octreotide should not, in general, be given as the primary treatment to patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding. The use of octreotide should be considered in patients who have persistent bleeding on optimal medical management, including PPIs, and are poor surgical risks (eg, those with multiple comorbidities already in the hospital).

[PubMed: 9412308]

[PubMed: 12145792]

[PubMed: 9091801]

[PubMed: 17442905]

[PubMed: 10922420]

[PubMed: 20614440]

[PubMed: 12965978]

The goal of endoscopic therapy is to eliminate persistent bleeding and prevent rebleeding. Rebleeding is the greatest contributor to both morbidity and mortality. The ability to achieve sustained hemostasis is dependent on controlled access to the bleeding vessel, a relatively small vessel size, and the absence of significant coagulation defects.

Upper endoscopy provides diagnosis, prognosis, and therapy in patients with acute upper GI bleeding and is reasonably safe to perform in patients with upper GI bleeding (50% of complications are cardiopulmonary). Upper endoscopy is 90–95% sensitive at locating the bleeding site. Sensitivity increases when the procedure is done closer to the onset of the bleeding and decreases with increasing duration from time of onset. Most patients with upper GI bleeding should undergo an upper endoscopy within 24 hours of presentation as is currently recommended by guidelines. Studies in patients with nonvariceal upper GI bleeding have not found an overall advantage of early endoscopy (within 12 hours) in terms of rebleeding rate, need for surgery, or mortality, however patients with active upper GI bleeding may benefit from an early intervention. Endoscopy can offer therapeutic options including injection, cautery, placement of hemoclips, or a combination of therapies. Endoscopy can also predict the likelihood of persistent or recurrent bleeding based on recognition of the endoscopic stigmata of recent hemorrhage.

It is important to recognize the stigmata of recent hemorrhage, which are endoscopic findings in patients with bleeding peptic ulcers (Table 31–4). Patients with active bleeding seen at the time of upper endoscopy have a very high rate of ongoing bleeding, with rates as high as 90% if no intervention is performed (Plate 50). Patients who have nonbleeding visible vessels are also at high risk of further bleeding, as despite not having active bleeding at the time of endoscopy, rebleeding occurs in approximately 45% (Plates 51 and 52). Patients who have adherent clots that do not easily wash off have an intermediate probability of further bleeding (Plate 53). Approximately 25% of patients with adherent clots will have further bleeding, depending on what is underneath the clot; if there is an underlying nonbleeding visible vessel the rate is much higher, and if the clot base is clean the rate is much lower. Patients who are considered to be at low risk based on endoscopic stigmata of recent hemorrhage include those with flat spots, which have a 10% risk of further bleeding (Plate 54). Patients who have clean ulcer bases (Plate 55) or Mallory-Weiss tears, who do not have concomitant coagulopathies or use of medications that alter clotting, have a very low rate of further bleeding (<5%).

| Stigmata | Risk of Rebleedinga (%) | Mortality (%) | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active arterial bleeding | 55–90 | 11 | 10 |

| Nonbleeding visible vessel | 40–50 | 11 | 25 |

| Adherent clot | 20–35 | 7 | 10 |

| Oozing (without visible vessel) | 10–25 | NA | 10 |

| Flat spot | <10 | 3 | 10 |

| Clean ulcer base | <5 | 2 | 35 |

The endoscopic stigmata of hemorrhage can be difficult to interpret. Nonbleeding visible vessels cause the most difficulty. Nonbleeding visible vessels are raised protuberances from an ulcer bed that can be of any color, but they can be confused with flat spots. These may represent vessels, pseudoaneurysms, or clots and have a variable appearance.

The utility of endoscopic therapy for patients with bleeding peptic ulcers was first shown in 1987 in a sham-controlled trial of multipolar electrocoagulation versus sham endoscopic therapy. Endoscopic therapy resulted in a significant improvement in hemostasis, number of units of blood transfused, number of emergency interventions, hospital stay (in days), and hospital costs. The mortality rate showed a trend toward being lower in the group treated with endoscopic therapy. Since this report, endoscopic therapy has been the standard of care for patients with high-risk stigmata of recent hemorrhage. Patients who have active bleeding or are found to have nonbleeding visible vessels should undergo endoscopic hemostasis to improve outcomes.

Adherent clots are found in about 10% of ulcers and are associated with a rebleeding rate of 20–35%. The optimal management of adherent clots has been controversial. Although National Institutes of Health consensus guidelines for management of GI bleeding from 1989 recommended against endoscopic treatment of adherent clots, this assertion has been challenged by several studies showing the efficacy of endoscopic treatment of adherent clots. The technique to treat an adherent clot starts with the use of epinephrine injection in four quadrants at the pedicle of the clot. A snare is used to cold guillotine the clot 3–4 mm above its base. Care is taken not to shear off the clot, further irritate the area, or provoke bleeding. The base of the ulcer is then vigorously irrigated with fluid to expose any underlying stigmata. This technique in areas assessable for endoscopic treatment appears safe and facilitates endoscopic therapy. Any visible vessel exposed or active bleeding provoked is treated with cautery therapy. The available studies to date show improvement with endoscopic therapy compared to medical therapy using H2-blockers. This endoscopic technique along with medical therapy with PPIs has shown benefit in treatment of patients with adherent clots.

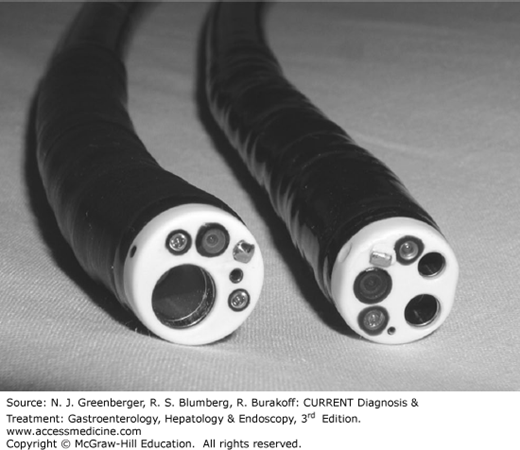

One of the challenges of managing patients with GI bleeding is visualization due to blood within the GI tract. This problem can be overcome by the use of a variety of techniques, individually or in combination. It is helpful to use double-channel or large-channel endoscopes, which allow for vigorous aspiration (Figure 31–2). It is also useful to use a water pump or water jet, which allows for vigorous irrigation, although many of the newer endoscopes incorporate water jet channels that are extremely useful. It is not necessary to routinely lavage patients with large volumes prior to upper endoscopy, even in those with large upper GI bleeds. Additional suction devices can be placed on the endoscope to facilitate removal of blood and clots directly during endoscopy.

Intravenous erythromycin (250 mg bolus or 3 mg/kg over 30 minutes) can be used as a prokinetic drug to increase gastric emptying and clear the stomach of blood. Erythromycin is given intravenously 30–120 minutes prior to endoscopy. The use of erythromycin significantly improves the quality of the gastric examination. This is a useful adjunctive treatment in patients with large GI bleeds with retained blood in the stomach. It can be used either initially or after an endoscopy shows large amounts of blood remaining in the stomach with withdrawal of the endoscope and erythromycin can be used before proceeding again with endoscopy. There are reports that metoclopramide given before endoscopy can also improve the quality of the gastric examination. In general, promotility agents should not be used routinely before endoscopy to increase the diagnostic yield but should be considered in patients suspected or found to have large amounts of blood or clot in their stomachs.

[PubMed: 21615438]

[PubMed: 15492601]

The current endoscopic modalities to treat nonvariceal GI bleeding include the use of injection therapies (primarily with dilute epinephrine), contact thermal therapies including heater probes, monopolar probes and bipolar probes, the use of noncontact thermal methods (argon plasma coagulation), mechanical treatments including a variety of hemoclips and band ligation techniques, and a combination of the preceding treatment modalities (typically injection therapies combined with one of the other modalities).

Injection therapies reduce blood flow primarily by local tamponade. However, the use of vasoconstricting agents, such as epinephrine (diluted 1:10,000 to 1:100,000), can further reduce blood flow. This type of therapy may not be beneficial in the setting of active bleeding of fibrotic or penetrating ulcers. Injection therapy as monotherapy is not felt to be as efficacious as other monotherapies and should not be used as the only modality of treatment. A high dose of injected epinephrine is more likely to cause cardiovascular side effects (especially when injected in the region of the esophagus).

Use of thermal methods to control nonvariceal upper GI bleeding is quite widespread. At the current time, bipolar cautery is the thermal modality used most extensively, as it has the advantage over heater probes of being able to be used perpendicularly or tangentially. The bleeding vessel is compressed and then coagulated to provide “coaptive coagulation.” The larger 10 French probes need to be placed via a therapeutic instrument and are generally more effective than the smaller 7 French probes. A relatively low wattage (10–15 watts in the duodenum; 15–20 watts in the stomach) is used for a prolonged time (8–12-second pulses) for each treatment pulse. Four to six pulses are typically used to provide effective treatment using moderate pressure. The end point of treatment is reached when the involved vessel completely flattens out and there is no further bleeding. A monopolar probe is available for treatment of GI bleeding, however its exact role in the management of patients with acute upper GI bleeding has to be further evaluated before its use can be advocated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree