CT: computed tomography.

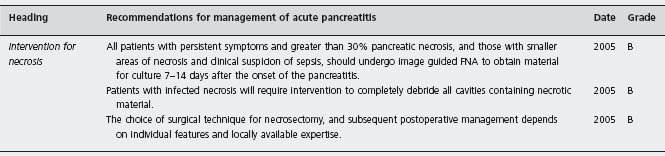

Grade indicates a recommendation based on: A, at least one randomised controlled trial as part of evidence of overall good quality and consistency;

B, clinical studies without randomisation; C, expert consensus.

aIndicates recommendations that should be reconsidered in light of new evidence.

USA indicates that overall mortality from acute pancreatitis is falling and is now less than 2% [13].

Diagnosis

Although amylase is widely available and provides acceptable accuracy of diagnosis, where lipase is available it is preferred for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Lipase is more specific and more sensitive than amylase. Amylase levels generally rise within a few hours after the onset of the symptoms and return to normal values within 3–5 days. However, serum lipase concentrations remain high for a longer period of time than do amylase concentrations, which gives slightly greater sensitivity for lipase than for amylase in patients with delayed presentation [14].

The correct diagnosis of acute pancreatitis should be made within 48 hours of admission. Although this may strain support and diagnostic facilities, the risk of missing an alternative life-threatening intra-abdominal catastrophe demands full investigation. Where doubt exists, imaging may be useful for diagnosis: ultrasonography is often unhelpful and pancreatic imaging by contrast enhanced CT provides good evidence for the presence or absence of pancreatitis.

Clinical diagnosis is usually straightforward, but overlap may exist with the clinical presentation of perforated viscus or gangrenous bowel. These serious alternative diagnoses may require urgent intervention and in case of doubt they must be excluded, usually by CT. It has been known for many years that contrast-enhanced CT shortly after admission has 87–90% sensitivity and 90–92% specificity to confirm the diagnosis of pancreatitis [15–17].

The presence of two of three diagnostic features (typical abdominal pain, elevated concentrations of serum amylase, or lipase above three times the upper limit of normal, and the presence of inflammatory changes in and around the pancreas on abdominal CT) confirms the diagnosis. These cutoffs for lipase and amylase are widely accepted [18], but the World Association Guidelines [10] point out that:

Pancreatic enzymes are released into the circulation during an acute attack. Levels peak early and decline over 3–4 days. An important concept derives from this: the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis should not rely on arbitrary limits of values three or four times greater than normal, but values should be interpreted in light of the time since the onset of abdominal pain.

Severe acute pancreatitis

In 1992, our understanding of acute pancreatitis was greatly improved by a consensus conference that took place in Atlanta [19]. This conference defined the terminology of acute pancreatitis and its complications, and has been the basis for much progress in improved management. However, some problems with terminology and definitions have been noted in the Atlanta document. Currently, the International Association of Pancreatology is attempting to revise these definitions by international consensus, focusing on the diagnosis and imaging of severe acute pancreatitis during two distinct phases: the first week (early phase characterized by Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome, SIRS, and organ failure), and a later phase characterized by depressed immune response and local complications, especially pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis. This consensus, led by Doctors Michael Sarr and Peter Banks, aims to collate the views of numerous pancreatic specialists around the world and to present an evidence base to shape clinical practice for the next decade.

Definition of severe pancreatitis

The definitions of severity, as proposed in the Atlanta criteria, should be used. However, organ failure present within the first week, which resolves within 48 hours, should not be considered an indicator of a severe attack (UK Guidelines 2005).

The Atlanta criteria [19] for severe pancreatitis remain widely accepted. In this definition, severe acute pancreatitis is characterized by the presence of any systemic or local complication. Other criteria of severe disease accepted by the Atlanta conference include the presence of a high Ranson or APACHE-II score (which are markers for systemic complications). The Atlanta criteria represent the first attempt to define cutoff values for organ failure in acute pancreatitis (Table 24.2). This was a useful step to clarify thinking about systemic complications, but it has become clear that the crossing of a threshold for organ failure is an inadequate definition for severe acute pancreatitis.

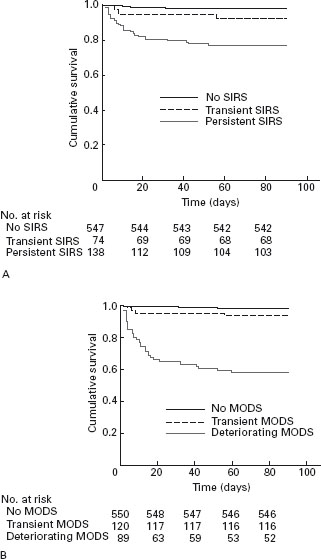

It is now understood that organ failure in acute pancreatitis is preceded by a phase of activation of the Systemic Inflammatory Response syndrome (SIRS) [20, 21]. The presence of SIRS is clinical evidence of inflammation (Table 24.3), and indicates high risk of progression to complications, but SIRS may resolve without consequence. However, the presence of SIRS in patients on admission to hospital is associated with increased risk of organ failure and death [21]. If SIRS persists for more than 48 hours beyond admission to hospital, the mortality rate rises to more than 20% [21], and the patient should be regarded as having severe pancreatitis (Figure 24.1).

Since the beginning of this century, it has become clear that the crucial feature of severity in relation to systemic complications during the first week of acute pancreatitis is the duration of organ failure, and that organ failure which resolves during the first week is associated with a very low mortality rate [22]. We showed in a national sample from 78 hospitals [23] that persistence of organ failure for more than 48 hours during the first week of the attack is associated with a 35% risk of fatal outcome. These patients also have a high risk of local complications. Others have confirmed this observation [21, 24, 25], and it is now established that persistent organ failure (>48 hours) during the first week of illness is part of the definition of severe acute pancreatitis.

The severity of early organ failure has also been shown by some authors [26, 27] to be associated with high risk of fatal outcome, but the interaction between severity and duration of organ failure has not been clarified.

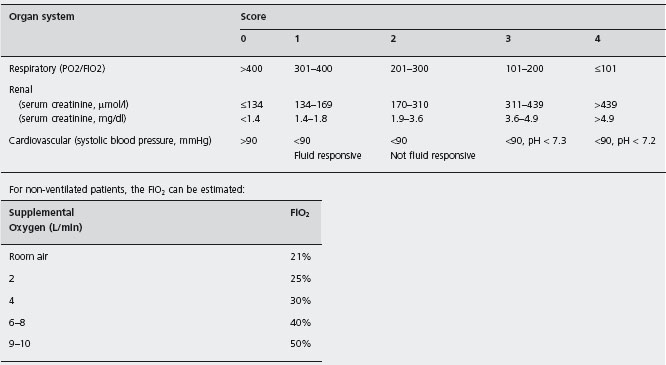

Three organ systems are usually sufficient to assess organ failure: respiratory, cardiovascular and renal. In our study of 290 patients with predicted severe acute pancreatitis, these organs were always involved in patients with persistent organ failure, and only 3 of 71 patients with transient organ failure did not have one of these systems affected [23]. Organ failure is easily defined in accordance with the Marshall scoring system [28] as a score ≥2 for at least one of respiratory, renal or cardiovascular function (Table 24.4). The full Marshall score (which includes the Glasgow coma score and platelet count) and the SOFA scoring system, which takes account of inotropic and respiratory support for patients managed in a critical care unit [29], may also be used for assessment of more severely ill patients with multiple organ/system failure. All these scores can be determined at presentation and daily to create a record of the presence and the severity of organ failure during the first week.

Table 24.2 Atlanta criteria for severe acute pancreatitis (16).

| Criteria for severe acute pancreatitis – presence of one or more of the following: (1) Ranson score during the first 48 hours, 3 or more (2) APACHE II score at any time, 8 or more (3) Presence of one or more organ failures (4) Presence of one or more local complications | ||

| Organ failures include: (1) Shock: systolic blood pressure,less than 90mmHg (2) Pulmonary insufficiency: PaO2 on room air, 60mm Hg or lower (3) Renal failure: serum creatinine, >2mg/dL after fluid replacement (4) gastrointestinal bleeding: blood loss more than 500mL/24 hours (5) coagulopathy: thrombocytopenia hypofibrinogenemia fibrin split products in plasma (6) severe hypocalcemia: calcium 7.5mg/dL or lower | ||

| Local complications include (1) pancreatic necrosis (2) pancreatic abscess (3) pancreatic pseudocyst |

Table 24.3 Definition of SIRS [17]. Severe pancreatitis is diagnosed if SIRS criteria persist for >48 hours.

| SIRS is defined by the presence of two or more of the following: | |

| Pulse | >90 beats/min |

| rectal temperature | <36°C or >38°C |

| white blood count | <4000 or >12,000 per mm3 |

| respirations | >20/min |

| or PCO | <32mmHg |

Figure 24.1 SIRS and organ failure in the first week are associated with high risk of fatal outcome (reproduced from Mofidi et al. [21]).

Prediction of severity

Severity stratification should be made in all patients within 48 hours. It is recommended that all patients should be assessed by the Glasgow score and CRP. The APACHE II score is equally accurate, and may be used for initial assessment; it should be used for ongoing monitoring in severe cases.

Available prognostic features which predict complications in acute pancreatitis are clinical impression of severity, obesity, or APACHE II >8 in the first 24 hours of admission, and C-reactive protein levels >150mg/l, Glasgow score 3 or more, or persisting organ failure after 48 hours in hospital.

These recommendations are still relevant, but a new simple scoring system has been reported (see below).

The management of acute pancreatitis is supportive; mild attacks resolve without specific measures other than ensuring adequate analgesia, oxygenation and circulating volume. For many years it has been believed that early identification of patients with severe disease would be advantageous, leading to early institution of aggressive support for failing systems and early transfer to an appropriate critical care facility. This approach led to many reports of various tests and scoring systems designed to predict severe disease. As noted above, we now identify such patients by the presence of specific clinical markers of severity, especially the presence of persistent SIRS, or persistent organ failure. However, the observation of high risk predictive scores (e.g. Ranson, Glasgow, APACHE II) or high levels of confirmed markers or risk factors of severe disease (C-reactive protein >150 mg/l [10, 30], BMI > 30 [12, 31]) may help focus clinical attention on potentially ill patients.

Clinical markers of severity and predictive scores

Table 24.5 summarizes features that predict a severe attack of acute pancreatitis and that are available shortly after admission to hospital. Age is an independent risk factor, and age >70 years is associated with 17% mortality risk [32]. Obesity is a risk factor for complications and death [31]. The mechanism of this increased risk is unclear, but it seems that obesity is associated with an increased inflammatory response [33, 34]. Other proposed mechanisms include greater risk of respiratory complications and the presence of poorly perfused fat in and around the pancreas, increasing the risk of pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis.

Table 24.4 Criteria from the Marshall Scoring System [25] which defi ne organ failure and measure its severity. Any value scoring 2 or more indicates an organ failure; the total score is a marker of the severity of organ failure.

Table 24.5 Features that predict a severe attack, that are present within 48 hours of admission to hospital. Modifi ed from reference 12 .

| Initial assessment | Clinical impression of severity |

| Body mass index >30 | |

| Pleural effusion on chest radiograph | |

| APACHE II score >8 | |

| 24 h after admission | Clinical impression of severity |

| APACHE II score >8 | |

| Glasgow score 3 or more | |

| Persisting organ failure, especially if multiple | |

| C reactive protein >150 mg/l | |

| 48 h after admission | Clinical impression of severity |

| Glasgow score 3 or more | |

| C reactive protein >150 mg/l | |

| Persisting organ failure for 48 h | |

| Multiple or progressive organ failure |

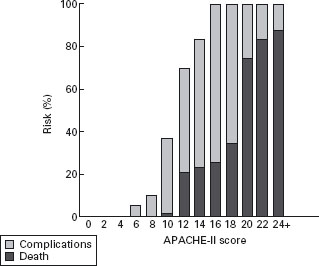

Objective parameters should be used to support the clinical examination in the first 24 hours of admission, as clinical examination is specific, but it is not sensitive when used alone [12]. The APACHE II score is widely used as a predictor of severity, and for monitoring progress early in the illness. The Atlanta criteria selected a cutoff score of 8 or more to define severe disease. This cutoff in the first 24 hours identifies almost all patients who will develop a complication. In a meta-analysis of three well-documented series comprising 627 cases (20% severe), Larvin [35] found no deaths in patients with initial APACHE II score below 10. A score of 10 or 11 was very unlikely to lead to death, but scores of 12 or more had a mortality rate over 20%, increasing with higher initial scores (Figure 24.2).

Recently, the Early Warning Score (EWS), based on routine nursing observations, and widely used to monitor the clinical condition of ill patients, has been proposed as a simple means of identifying high risk patients [36, 37]. The EWS also responds to the dynamic nature of the illness: deterioration of scores is associated with a worse outcome [36]. The ability of this system to predict severe pancreatitis has been compared with APACHE II scores, modified organ dysfunction scores, Glasgow scores, CT severity index and Ranson criteria for 181 admissions with acute pancreatitis. Scores were calculated daily for the first three days. The APACHE II and EWS performed best in receiver operating curve analysis, with similar areas under the curve (APACHE II 0.876, 0.892 and 0.911; EWS 0.827, 0.910 and 0.934, on days 1, 2 and 3 respectively). These findings suggest that the simple and easily assessed EWS could be used at the bedside to monitor progress and identify severe acute pancreatitis soon after admission to the hospital. In particular, EWS reflects the dynamic nature of the illness in the same way as SIRS and organ failure. This simple clinical observation should permit reliable identification of patients at risk of complicated or fatal course in any hospital setting. Importantly, improvement in the EWS (or other scores discussed above) is reassuring that the patient is likely to recover without complications.

Figure 24.2 Percentage risk of death or complications associated with different initial APACHE-II scores (reproduced from Larvin [35]).

A large population based survey [13] has developed and validated a predictive system for severe acute pancreatitis based on easily obtained features present at the time of admission to hospital. The authors reviewed records of 17,992 patients for features associated with severe disease, that were present within 24 hours of admission. They identified five independent predictors: blood urea nitrogen >25mg/dL (>8.93mmol/L), impaired mental state, SIRS, age > 60 years and pleural effusion on chest X-ray (acronym BISAP score). Allocation of one point for each feature gives a simple BISAP score, which identifies low risk patients with low score, and high risk groups with a >10% risk of death for scores of 4, and >20% risk of death for scores of 5. The strength of this report is that the predictive ability of the scores was confirmed in a new sample of patient records, comprising over 18,000 patients treated in the years 2004–2005. The development and validation cohorts had mortality rates of 1.9% and 1.28% respectively, which suggests that this study used “real world” data including all cases of mild disease in the contributing hospitals. The BISAP score promises to simplify the assessment of acute pancreatitis, particularly by the rapid identification of the large majority of patients who are at low risk of complications and death.

Laboratory markers

Plasma C-reactive protein is accurate, but delayed in its response, not peaking until 72–96 hours into the illness. A value >150mg/l identifies patients at risk of pancreatic necrosis and potentially fatal outcome [12]. There is some evidence that serum or urine concentrations of the trypsino-gen activation peptide (TAP) [38–41] and urine anionic trypsinogen 2 [42–44] might be useful to predict severity, although to date only the trypsinogen 2 test is available as a rapid bedside test.

Another promising early marker of severity is procalci-tonin (PCT). Despite some contrary views (based on relatively small numbers) [45, 46], there is considerable evidence that PCT is a useful early marker of severe disease, and especially of pancreatic necrosis, or infected necrosis. A meta-analysis of the early evidence [47] reviewed nine reports. There was considerable variation of methodological quality. Considering only high quality reports, the sensitivity and specificity of PCT in the first 24 hours in hospital to predict severe disease were 82% and 89%, with an area under the curve value of 94%, indicating very good discrimination. The meta-analysis indicated that PCT may be especially useful for the identification of patients at risk of infected necrosis.

Two further studies support these findings. Rau has long advocated using this marker, and her latest publication [48] provides more evidence from a study of 104 patients in five European centers enrolled within 96 hours of symptom onset. Initial PCT concentrations were significantly elevated in patients with pancreatic infections and associated multi-organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), all of whom required surgery (n = 10), and in non-survivors (n = 8). PCT levels were only moderately increased in seven patients with pancreatic infections in the absence of MODS, all of whom were managed non-operatively without mortality. A PCT value of 3.5ng/ml or higher on two consecutive days had a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 88% for the assessment of infected necrosis with MODS or non-survival. This prediction was possible on the third and fourth day after onset of symptoms with a sensitivity and specificity of 79% and 93% for PCT 3.8ng/ml or higher. Another study of 40 patients (11 severe) supports these findings [49]. There is now strong evidence that early estimation of procalcitonin can identify patients at risk of infected necrosis or death, and the test may be repeated to improve the detection of these most severe cases.

Role of CT in acute pancreatitis

During the first week

As noted above, at the time of admission to hospital CT may be required if the diagnosis is in doubt: this may arise with delayed presentation, for example when the plasma enzyme levels have fallen below the diagnostic threshold. Sometimes CT may be helpful to exclude other diagnoses, such as perforation or gangrene of bowel. There is no evidence that early CT is helpful in the management of confirmed acute pancreatitis. Indeed, the UK guidelines [12] recommend that the first scan be delayed until 6–10 days after onset of symptoms. Arguments against early CT in all cases of pancreatitis are that early CT with intravenous contrast has the potential risk of worsening the renal impairment, and that an early CT may underestimate the full extent of pancreatic necrosis, which may evolve for at least four days after the onset. Most importantly, CT is unlikely to change management decisions in the first week. At this stage, treatment is supportive, and surgical or other intervention is avoided, and CT does not affect clinical decision-making.

Early CT may be used to assess the severity of the illness if this is required, for example to stratify patients in treatment trials. Balthazar and colleagues [50] proposed the CT severity index (Table 24.6) based on the grade of inflammation and the extent of pancreatic necrosis determined by enhancement. The sum of these two scores is used to calculate the severity index.

After the first week

Patients with persisting organ failure, signs of sepsis, or deterioration in clinical status 6–10 days after admission will require CT. CT is usually performed after 6–10 days in patients with persistent SIRS or organ failure to assess local complications such as fluid collections and necrosis [12, 50]. There is some evidence that MRI identifies necrosis and fluid collections better than does CT [51], although the practical difficulty of ensuring MR compatible equipment attached to a patient with organ failure may be a problem in some settings.

The Atlanta criteria are not clear on the distinction between fluid collections, pseudocyst and necrosis. The current international consensus revision of the Atlanta criteria mentioned above is likely to advocate the use of contrast enhanced CT for the characterisation of morphological changes in and around the pancreas, after the first week of the illness, and will probably recognise a number of local complications, namely pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis, acute peripancreatic collections within four weeks from onset of symptoms, and pseudocyst and walled off pancreatic necrosis more than four weeks from onset. The extent of pancreatic necrosis on CT is useful information, because this is related directly to the risk of local and systemic complications [52, 53].

Table 24.6 Computed tomography (CT) grading of severity.

| Computed tomography (CT) grading of severity | Score |

| CT grade | |

| (A) Normal pancreas | 0 |

| (B) Oedematous pancreatitis | 1 |

| (C) B plus mild extrapancreatic changes | 2 |

| (D) Severe extrapancreatic changes including one fluid collection | 3 |

| (E) Multiple or extensive extrapancreatic collections | 4 |

| Pancreatic necrosis (extent) | |

| None | 0 |

| Up to one third | 2 |

| Between one third and one half | 4 |

| More than half | 6 |

| CT severity index = CT grade + necrosis score | |

| Observed rates of complications and death related to CTSI score | Complications |

| 0–3 | 8% |

| 4–6 | 35% |

| 7–10 | 92% |

| Deaths | |

| 0–3 | 3% |

| 4–6 | 6% |

| 7–10 | 17% |

Modified from the World Association guidelines [10] and based on Balthazar and colleagues [47].

CT is unreliable for the discrimination of pseudocyst from necrosis. The Santorini consensus conference [30] recommended that either ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) should be used to differentiate between fluid and necrotic tissue. In practice, it is wise to consider all localized collections following necrotising pancreatitis to be pancreatic or peripancreatic necrosis until proved otherwise.

Organization of care

All cases of severe acute pancreatitis should be managed in an HDU or ITU setting with full monitoring and systems support. Every hospital that receives acute admissions should have a single nominated clinical team to manage all patients with acute pancreatitis. Management in, or referral to, a specialist unit is necessary for patients with >3 0% necrosis or with other complications.

It seems self-evident that the care of these potentially difficult and seriously ill patients should be concentrated in the hands of interested clinicians with appropriate expertise. C5

Initial management and resuscitation

Early fluid resuscitation and oxygen supplementation are simple measures that seem likely to be helpful in early resolution of organ failure [54]. Whether these interventions significantly reduce the mortality rate is not known, but it seems sensible to provide simple circulatory and respiratory support designed to achieve rapid resolution of organ failure. C5 This approach may break the cycle of hypotension and hypoxaemia that can sustain and provoke more organ system failures. The fluid replacement with a mix of crystalloid and colloid solutions should aim to maintain good urine output (0.5 ml/kg) and can be monitored by central venous pressure reading in selected patients. Oxygenation ideally should maintain the arterial saturation above 95%. Oxygen saturations lower than this are associated with significant hypoxaemia [55].

Prophylactic antibiotics

The evidence for antibiotic prophylaxis against infection of pancreatic necrosis is conflicting and difficult to interpret. At present there is no consensus on this issue.

If antibiotic prophylaxis is used, it should be given for a maximum of 14 days. Further studies are needed.

It is pleasing to note that we now have evidence to resolve this issue, outlined below.

Since infected pancreatic necrosis is associated with high mortality rates (40%) and it is one of the leading causes of death in acute pancreatitis, many trials have been done to establish the role of prophylactic antibiotics in reducing the mortality rate and other infective and non-infective complications. The trials discussed up to 2005 had shown benefit for prophylaxis, but there were concerns that the improvements in outcome were seen for different end-points in different studies. The guidelines quoted above should be re-evaluated in light of the publication of more high quality evidence. An interesting analysis [56] has shown an inverse relationship between the quality of studies and the observed effect, i.e. as study quality improves, the differences in outcome diminish.

In discussing the available evidence, the UK guidelines noted:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree