13 Acute diarrhoea

Case

A 70-year-old man presents with crampy, left-sided abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea for 7 days. The patient has a background history of ischaemic heart disease and peripheral vascular disease. He also has bronchiectasis requiring regular courses of antibiotics.

Introduction

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiological mechanisms resulting in acute or chronic diarrhoea can be divided into several major groups: osmotic, secretory, exudative and abnormal motility (see Box 13.1).

Box 13.1 Pathophysiological mechanisms in diarrhoea

Osmotic diarrhoea results when a non-absorbable solute accumulates within the small intestine. The osmolality of the small intestine is adjusted to that of plasma by water influx across the small bowel and watery diarrhoea results. Examples of osmotic diarrhoea include carbohydrate malabsorption (such as lactase deficiency) and ingestion of magnesium salts. Osmotic diarrhoea ceases when the poorly absorbed solute is removed from the diet.

The fourth major cause is increased transit in the small bowel or colon: abnormal intestinal motility. Increased transit may occur with thyrotoxicosis (due to excess thyroid hormone), diabetes mellitus or in the irritable bowel syndrome (Ch 7).

Clinical Approach to Acute Diarrhoea

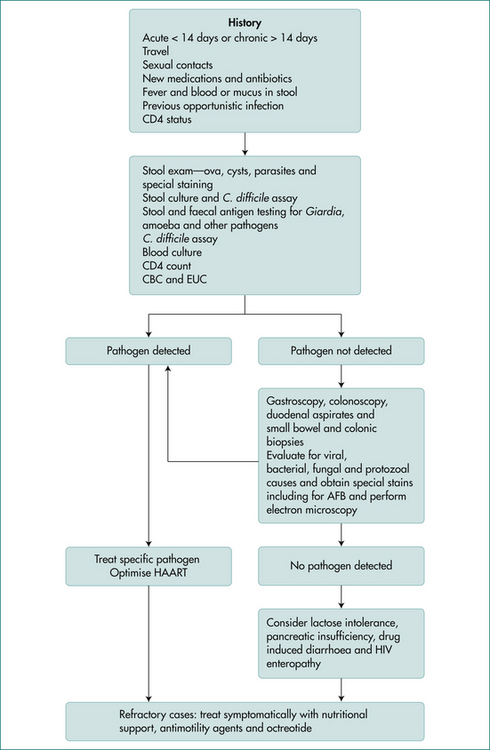

The causes of diarrhoea vary depending on the type of practice, but in all settings gastrointestinal infections are a common cause of acute diarrhoea (Box 13.2). It is clinically useful to divide acute causes of diarrhoea into clinical syndromes, watery (non-inflammatory) diarrhoea, blood (inflammatory) diarrhoea, food poisoning, diarrhoea in the traveller, diarrhoea associated with recent antibiotics or other drug use and diarrhoea in the HIV-positive (Fig 13.1) or male homosexual patient. Overlap may occur between the categories. Of course, an illness may begin as watery diarrhoea, only to progress to bloody diarrhoea later.

The clinical approach to those with acute diarrhoea should focus initially on:

History

A careful history is important in evaluating patients with acute diarrhoea and in separating minor from severe illness. Features that suggest the diarrhoea may not be self-limiting include severe diarrhoea, blood in the stool, severe abdominal pain or a high fever (Box 13.2).

Ask about the duration of symptoms as well as severity. An abrupt onset of diarrhoea, which then gradually improves, suggests an infective process. Systemic features with infectious diarrhoea include fever, myalgia, malaise, nausea and vomiting. The onset of diarrhoea with food poisoning is often severe but short-lived. With prolonged watery diarrhoea, volume depletion is more likely to develop, especially when there is associated vomiting. Large volume, watery diarrhoea may be of small bowel origin. The presence of blood in the stool is usually due to an intestinal inflammatory process (see Box 13.3).

Box 13.3 Causes of acute watery and blood diarrhoea

Investigations

Those with minor resolving diarrhoea need no investigations and no specific therapy beyond maintenance of hydration. Those with features outlined in Box 13.2, where a definitive diagnosis is likely to alter management and outcome, should usually be further investigated. Those diagnostic tests should be targeted, where possible, towards a specific diagnosis according to clues from the history and physical examination.

Stool examination

Specific testing for various pathogens should be requested where appropriate. If the epidemiological settings suggest the possibility of C. difficile infection, a specific request for that pathogen as well as C. difficile toxin should be made. Viral cultures may need to be considered in immunocompromised patients.

Therapy

Antibiotics

Antibiotics should be avoided in the routine treatment of acute diarrhoea. They are usually ineffective in reducing the duration of the illnesses and in some cases may prolong excretion of the pathogen. They also have significant side effects and indiscriminate use will increase drug resistance. There are a limited number of situations where antibiotics may be helpful. Box 13.4 outlines the indication for antibiotics and these are discussed in more detail under disease headings.

Conditions Causing Food-borne Illnesses

Food-borne illnesses are caused by the consumption of contaminated food and result in significant worldwide morbidity and mortality. They can be caused by the consumption of bacteria or bacterial toxins, viruses, parasites or chemicals.

Some of the common causes of food-borne illnesses are discussed below under aetiological headings.

Bacterial food-borne illnesses

Vibrio parahaemolyticus

V. parahaemolyticus is associated with seafood and causes food poisoning outbreaks after the ingestion of shellfish or raw fish. It causes explosive watery diarrhoea with an incubation period of 12–24 hours. The diarrhoea may be associated with nausea, vomiting and fever and occurs in about 25% of patients. Occasionally, a dysenteric syndrome may result with blood diarrhoea. A specific request must be made to the laboratory for culturing the organism. Symptoms are generally short-lived and require no specific therapy.