The inflammatory grade is typically determined by adding up the individual scores for inflammation in the portal tracts, interface activity, and lobular inflammation to reach a composite inflammatory grade, although some systems do not use all three categories of inflammation. For example, the Metavir uses only the interface activity and lobular activity components to determine the inflammatory grade. The inflammation in these three areas of the liver (portal tracts, interface activity, and lobular), all strongly covary in chronic viral hepatitis, with portal inflammation and interface activity having the strongest association.2 In other words, as portal inflammation increases, the amount of interface activity also increases. Lobular inflammation, although still associated with the other two, is less tightly linked.

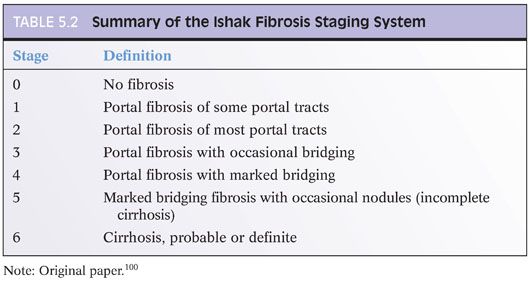

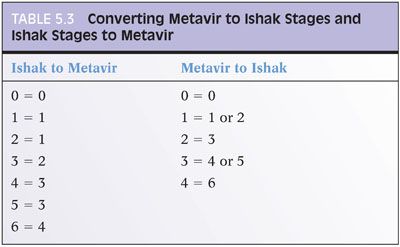

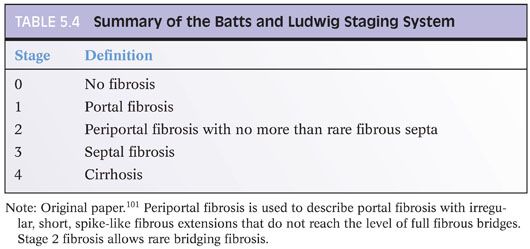

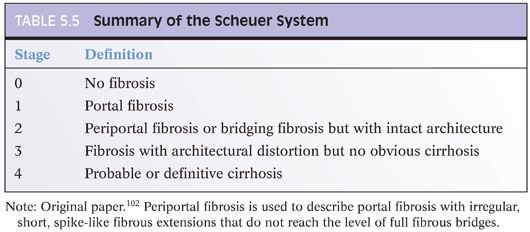

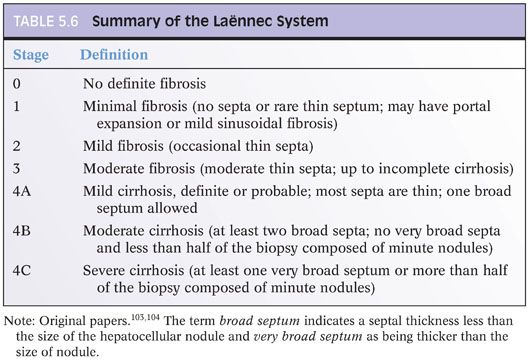

Chapter 2 discusses the pros and cons of using a formal staging and grading schema. The full discussion will not be repeated here, but perhaps, it is worthwhile restating a few of the key points: (1) Use the schemas if you or your clinical team find them useful, but do not forget that they are simply a communication tool and not a substitute for the pathology itself; (2) these schemas were originally designed for research studies and are most useful in that setting; any additional value over traditional pathology descriptions for routine patient care has not been identified to date and is unlikely to be in the future (this may be a surprise to the reader, but is true!); (3) the schemas use words and numbers as synonyms, so although “Metavir stage 1” does sound more impressive than “portal fibrosis,” they are in fact the same; (4) grading and staging schemas do not create a “universal” system that eliminates interpretive variability—in fact, the schemas themselves can introduce another layer of potential interpretive variability; and (5) if you do use a formal system, please state in the report which one you are using and use it exactly as described in the paper that defined the system—this would not be the time to demonstrate your individuality and creativity by “improving the system” with personal changes, even if they are brilliant. For those who would like to read more about fibrosis staging systems, an excellent, thoughtful, and thorough article has been published by Goodman.3 Another excellent article has been published by Guido et al.4 There are other fine review articles, but the author recommends these two articles as a good place to start. Regardless of the approach you decide, all liver pathology reports should indicate the amount of fibrosis, and the fibrosis is best determined by special stain, for example, trichrome or Sirius red.

When grading fibrosis, there are several pitfalls to avoid. These pitfalls are also discussed and illustrated in the Chapter 4 and are important to know. These pitfalls are not unique to viral hepatitis and can be seen in fibrosis from any of the major causes of chronic hepatitis including viral hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, fatty liver disease, and drug effect. Of these diagnostic pitfalls, the two most common are (1) marked portal expansion by inflammation or bile ductular proliferation that leads to overstaging of portal fibrosis and (2) areas of bridging necrosis or panacinar necrosis that mimic bridging fibrosis and also lead to overstaging.

RISK FACTORS FOR FIBROSIS PROGRESSION

The risk factors for fibrosis progression have been most extensively studied in chronic hepatitis C, but the general principles are likely broadly applicable. Risk factors for fibrosis progression include fibrosis on prior biopsy, male sex, older age at first infection, length of infection, HIV5 or hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection,6 and additional liver diseases such as fatty liver7 from the metabolic syndrome or from alcoholic liver disease. Although fatty liver from the metabolic syndrome or alcohol use is recognized as increasing the risk for fibrosis progression, an increased risk for fibrosis progression is less clear when the fatty liver is caused solely by hepatitis C, usually viral genotype 3.8 Iron overload that is moderate or marked also likely increases the risk for fibrosis progression.9 Fibrosis progression is not linear overtime but appears to progress more rapidly with advance fibrosis. For example, progression from portal fibrosis to bridging fibrosis tends to take longer than progression from bridging fibrosis to cirrhosis.

HEPATITIS A

Hepatitis A is an RNA virus that is most commonly transmitted through the oral-fecal route, but sexual transmission and blood-borne transmission are also possible. It was first visualized by electron microscopy in 1973.10 Although an effective vaccine for hepatitis A has been available since the 1990s, hepatitis A is still an important cause of acute hepatitis. The virus is very stable at room temperatures and is resistant to low pH, giving it great ability to survive in the environment. Several of the world’s largest known epidemics of hepatitis A have been associated with eating raw seafood.11,12 The viral incubation period is 2 to 7 weeks. Overall, less than 30% of infected children will be symptomatic, whereas up to 80% of infected adults will have symptomatic hepatitis. Also, individuals with chronic liver disease, such as chronic hepatitis C or hepatitis B, have a high risk of fulminant hepatitis and fatality when superinfected with hepatitis A. Hepatitis A does not cause chronic hepatitis, but it can recur in the liver allograft of patients transplanted for fulminant hepatitis A.13,14

Biopsies are rarely performed in patients with acute hepatitis A because the diagnosis can be made by serologic studies. However, biopsies for acute hepatitis A are still occasionally performed when the diagnosis is not clinically evident. Biopsies in the setting of hepatitis A are more common when there is a relapsing course or a prolonged cholestatic course, both of which are discussed in more detail later. Histologically, acute hepatitis A manifests as a lymphocytic hepatitis with varying degrees of lobular and portal inflammation. In many cases, the portal inflammation is more striking than the lobular hepatitis.15,16 The portal infiltrates can also be rich in plasma cells.16,17 The lobular hepatitis can have a zone 3 predominance in some cases.16,17 In liver biopsies with marked hepatitis, the lobules may be cholestatic and the portal tracts may contain a mild bile ductular proliferation. Fibrin ring granulomas have also been rarely reported.18 Hepatitis A also causes fulminant liver failure and in the United States represents 3% of all cases of acute liver failure.19 Biopsies are not common in these cases but show marked inflammation and massive liver necrosis.

Overall, there are no histologic findings that will allow you to distinguish acute hepatitis A from other causes of acute hepatitis, including other viruses, drug effect, or autoimmune hepatitis. As noted earlier, acute hepatitis A can have a prominent plasma cell component in the portal tracts, so do not overinterpret this histologic finding as being diagnostic of autoimmune hepatitis. Fibrosis is not a component of acute hepatitis A and, when present, reflects an additional underlying liver disease with superimposed hepatitis A. The diagnosis of acute hepatitis A is made by antibody studies (hepatitis immunoglobulin M [IgM] positivity) or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for hepatitis A RNA.

In most individuals, hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection is self-limited and the laboratory findings and biopsy findings return to normal, although mild nonspecific inflammatory changes may persist for up to a year following the acute hepatitis.20 However, it is important to know that some patients have atypical courses of clinical disease. One of these atypical situations is relapsing HAV infection. In these cases, an individual previously diagnosed with acute hepatitis A will appear to recover but then has a hepatitis relapse. This pattern of relapsing hepatitis A is well documented, but is rare, and thus may lead to clinical uncertainty over the cause of liver disease, and then to a liver biopsy. The most common time interval between the first and second hepatitis peak is 4 to 7 weeks. The pathology in relapsing hepatitis A typically shows a mild to moderate portal and lobular hepatitis without specific features. There may be mild lobular cholestasis. Rarely, the hepatitis can be granulomatous.21

A second unusual clinical course is prolonged cholestasis after the hepatitis A infection. In most individuals, the bilirubin returns to normal within about 4 weeks after presentation. However, in approximately 2% of cases, there can be prolonged elevations in bilirubin.22 Biopsies in these cases typically show residual and often mild portal and lobular chronic inflammation along with mild lobular cholestasis (eFigs. 5.1 and 5.2). Features of biliary obstruction are not present, and the cholestasis is typically intrahepatic and canalicular.

HEPATITIS B

HBV is a partially double-stranded DNA virus. Hepatitis B virions can be present at high levels in many different body fluids. Most new infections are transmitted through sexual activity or through blood or blood products. Acute hepatitis B has very different outcomes depending on the age of infection. Acutely infected neonates have a 90% risk of developing chronic hepatitis B, whereas acutely infected adults have about a 5% chance of going on to chronic hepatitis.

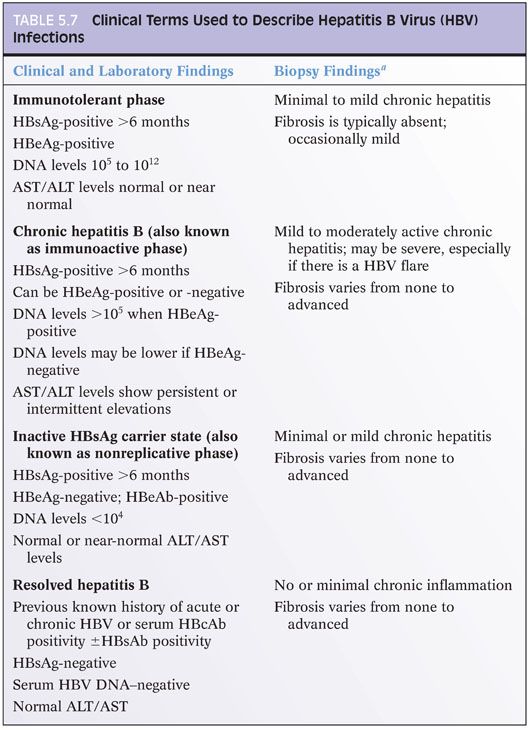

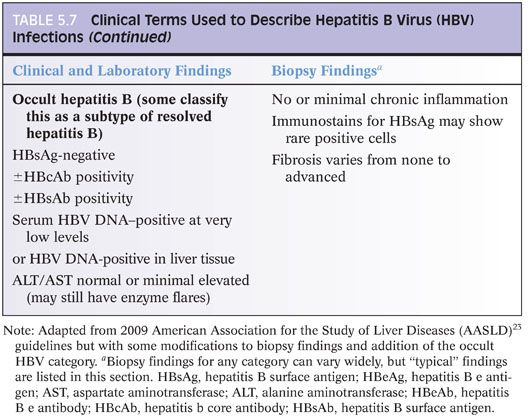

Based on recent guidelines,23 hepatitis B infection is clinically categorized into those with immunotolerant hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis B, inactive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) carrier state, and resolved hepatitis B (Table 5.7). Occult hepatitis B is an additional category, wherein HBsAg is undetectable, but DNA levels are present in the blood or liver tissues. This information on clinical categories will not help you at the microscope, but it is the main conceptual framework around which clinicians and researchers organize clinical care and research studies, so it is useful to know as you discuss cases with your colleagues and as you read the literature. However, it is important to know that HBV clinical categories do not correlate very well with histologic findings nor are there consistent correlates between viral load and histologic findings or serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and histologic findings. For example, individuals with low or normal ALT levels may still have significant inflammation and fibrosis on liver biopsy.24,25 Nonetheless, there are a few broad correlates that have been repeatedly observed. First, those individuals in the immunotolerant phase tend to show minimal or mild inflammation and no or mild fibrosis.26 Second, paired biopsies will typically show less inflammation after hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion, but such paired specimens are most likely to be encountered in the setting of a clinical trial.

Acute Hepatitis B

Patients with acute hepatitis B are rarely biopsied because the diagnosis can be made by serologic studies and serum PCR for HBV nucleic acids. However, biopsies do occur when clinical testing is incomplete or the results are ambiguous. In acute hepatitis B, the portal tracts show predominantly lymphocytic infiltrates. The lobules show moderate to marked lymphocytic inflammation, hepatocyte swelling, and scattered apoptotic bodies. Kupffer cells are typically prominent. The lobules may also be cholestatic with more severe degrees of inflammation or in older individuals. With more severe hepatitis, areas of confluent or bridging necrosis may be seen. The acute hepatitis is otherwise rather nondescript. Do not look for hepatitis B ground glass inclusions—they are present only in cases of chronic hepatitis.27–29 Immunostains for HBsAg are also typically either negative or only focally positive in acute infections.30

Chronic Hepatitis B

The most common reason for biopsy with chronic hepatitis B is to determine the grade of inflammation and the stage of fibrosis. The inflammation patterns in chronic hepatitis B are not specific and may show significant overlap with other causes of chronic hepatitis, such as hepatitis C, autoimmune hepatitis, or drug effects. The overall body of literature indicates that lymphoid aggregates and bile duct lymphocytosis are somewhat less common in hepatitis B compared to hepatitis C, but such observations are not diagnostically useful for separating the two.

PORTAL TRACT CHANGES. Chronic hepatitis B typically shows mild to moderate portal chronic inflammation. The portal inflammation will be predominately lymphocytic, and discrete lymphoid aggregates may be present in 10% to 20% of cases.31 The inflammation in the portal tracts may extend into the lobules and be associated with injury and disruption to the row of hepatocytes that are immediately adjacent to the portal tract. This finding was previously called periportal hepatitis or piecemeal necrosis, but now the preferred term is interface activity. Interface activity, however, is etiologically nonspecific and can be seen with variable prominence in chronic hepatitis from any cause, ranging from drug reactions to viral hepatitis to autoimmune hepatitis, and generally reflects the overall degree of inflammation. The bile ducts may show mild lymphocytosis and epithelial reactive changes (Poulsen lesion) in approximately 10% of cases.31

LOBULAR CHANGES. In chronic hepatitis B, the lobules typically show mild lobular chronic inflammation. Approximately 80% of cases will have lobular inflammation that ranges from minimal to mild, with most of the remaining showing moderate lobular inflammation. Marked lobular hepatitis is unusual outside of the setting of an HBV flare or hepatitis D virus (HDV) superinfection. In all cases, the lobular inflammation is predominately lymphocytic. Kupffer cells may be prominent in cases with moderate or marked lobular inflammation.

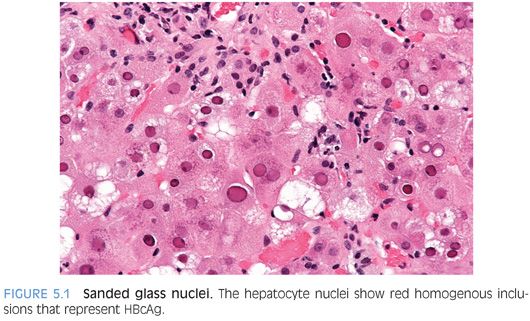

The hepatocytes may show nuclear inclusions composed of hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) that are called sanded glass nuclei (Fig. 5.1). These nuclear inclusions are most commonly seen in individuals with high viral replication levels32–35 and will stain positive for HBcAg by immunostain. Be aware that similar inclusions can be seen in patients without HBV, including those with HDV36 and in some cases apparently as an incidental finding, so do not make a diagnosis of HBV on the basis of finding sanded glass nuclei on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Of note, the HBcAg immunostain will also stain many hepatocyte nuclei positive that do not show sanded glass changes. Immunohistochemistry for HBcAg will also stain the cytoplasm in some cases, a finding that is dependent to some degree on the antibody used for immunohistochemistry and perhaps on the HBeAg status. A cytoplasmic staining pattern has been linked to somewhat higher overall grades of inflammation.33–35 Rarely, the nuclei of bile duct epithelial cells will also stain positive for HBcAg.

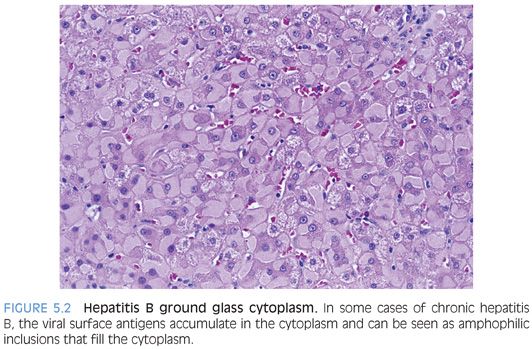

The cytoplasm of the hepatocytes may also show ground glass inclusions (Fig. 5.2). Ground glass inclusions are more common and more famous than sanded glass nuclei and are composed of HBsAg located within the smooth endoplasmic reticulum of the cell cytoplasm. Molecular studies find that the viral proteins in ground glass often have mutations,37 perhaps preventing viral proteins from normal release. The accumulation of viral proteins can also interfere with secretion of other cellular proteins, which accumulate and contribute to the ground glass appearance.38 Ground glass hepatocytes can be stained with Shikata orcein stain and with Victoria blue, but most centers now use immunostains. In many cases, the smooth endoplasmic reticulum proliferation that causes the ground glass change can also be enriched in glycogen molecules, and thus will be PAS-positive.

Immunostains for HBsAg will strongly stain ground glass hepatocytes as well as some hepatocytes that do not have ground glass change on H&E stains. Morphologically, ground glass hepatocytes demonstrate two commonly seen patterns, termed type 1 (eFigs. 5.3 to 5.5) and type 2 (eFigs. 5.6 and 5.7). Type 2 has a stronger connection to tumor genesis,39 although it is not clear if there is enough predictive power in this observation to make it a worthwhile addition to liver pathology reports. Hepatocytes can also have other less common staining patterns, including membranous staining and distinctive course granular cytoplasmic staining (eFigs. 5.8 and 5.9). Also of note, the H&E findings of ground glass type changes in hepatocytes are not specific for HBV because other disease processes can cause pseudoground glass changes that appear essentially identical on H&E stains to those induced by HBV. Drug effects are the most commonly cause of these pseudoground glass changes.40

One of the important clinical features of chronic hepatitis B is that there can be flares of increased viral replication that are associated with increased liver injury. Flares are often defined as aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/ALT elevations more than 2× the baseline value and more than 10× the upper limit of normal. In most cases, these flares are recognized clinically as part of the natural history of hepatitis B and are not biopsied. When they are biopsied, the findings are that of moderate to markedly active lobular hepatitis, often with zone 3 foci of necrosis. In some cases, there may be bridging necrosis or confluent panacinar necrosis. The differential for an HBV flare should always include HDV superinfection.

GRANULOMAS AND HEPATITIS B. About 1% to 2% of biopsies for chronic hepatitis B will have small epithelioid granulomas without polarizable material.41,42 Extensive clinical and pathology workups are typically negative,41 although it is still important to examine the granulomas with acid-fast bacillus (AFB) and Gomori methenamine-silver (GMS) stains. The significance of the granulomas is unclear but perhaps represents a propensity for the immune reaction to form small granulomas in some individuals.

LIVER CELL DYSPLASIA. The hepatocytes in chronic hepatitis may show findings that are called liver cell dysplasia or liver cell change. These findings are typically classified as large cell change/dysplasia or as small cell change/dysplasia. Whether the best term is change or dysplasia is still a matter of debate. Both of these findings are more common in chronic HBV than in other chronic liver diseases, but they are not unique to HBV. They are most commonly seen in liver specimens with advanced fibrosis. Small cell dysplasia refers to small discrete aggregates of hepatocytes with relatively little cytoplasm but otherwise normal nuclear and cytoplasmic cytology. In contrast, large cell change is defined by aggregates of hepatocytes with normal to abundant amounts of cytoplasm but with striking nuclear changes that include hyperchromasia, pleomorphism, and multinucleation. Both of these findings have been linked to hepatocellular carcinoma risk, although their prognostic value for future carcinogenesis remains poorly defined.

HEPATOCYTE ONCOCYTOSIS. Although this finding is not specific for chronic hepatitis B, distinctive nodules of oncocytic change (eFig. 5.10) seem to be more commonly found in chronic hepatitis B than in other diseases. The change can be seen in both cirrhotic (most commonly) and noncirrhotic livers, typically in individuals with long-standing chronic hepatitis B infection. The significance of this finding remains unclear.

IMMUNOSTAINS. Immunostains for HBsAg or HBcAg are not necessary for routine grading and staging of disease. They can be helpful when laboratory testing is not available or equivocal. Immunostain patterns have some broad correlates with the clinical category of disease (clinical categories of HBV disease are summarized in Table 5.7) and with the degree of inflammation but are not incorporated into current treatment guidelines. In the immunotolerant phase, there tends to be little lobular inflammation, lots of HBcAg positivity in hepatocyte nuclei (eFig. 5.11), and strong HBsAg staining of hepatocytes, often with a membranous pattern. As inflammatory changes increase, the amount of HBcAg nuclear positivity tends to decrease and the HBcAg cytoplasmic staining increase. HBsAg staining tends to decrease. Distinct, circumscribed aggregates of HBsAg-positive hepatocytes tend to be more common in livers of individuals in the inactive carrier state with advanced fibrosis.

FIBROSING CHOLESTATIC HEPATITIS B. Fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis B is a rare form of chronic HBV infection that is seen in patients who are immunosuppressed, typically those with solid organ transplants and high levels of immunosuppressants. In classic cases, the liver shows marked lobular cholestasis with hepatocyte swelling or ballooning degeneration, moderate ductular proliferation in the portal tracts, and pericellular and portal fibrosis on trichrome stain. The ductular proliferation often suggests obstructive biliary tract disease and biliary tract obstruction should be ruled out as part of the workup for such cases. The pericellular fibrosis is often more prominent in the periportal areas. The inflammatory changes are typically mild despite the marked ongoing liver injury. The viral levels are typically significantly elevated above baseline, and the pathology is thought to revolve around direct viral toxicity due to the high viral replication levels. There can be rapid progression to cirrhosis.

Cases with these classic and typical findings are often easy to recognize. However, it is important to realize that the classic changes in fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis B represent the end of a spectrum of findings, and you may also encounter cases in between. For example, there are cases of cholestatic hepatitis B in patients who are immunosuppressed and who may lack the fibrosis and portal tract changes, but whose lobular cholestasis appears to be associated with direct viral replication, because the histologic changes improve significantly with reduced immunosuppression.

HEPATITIS D

Hepatitis D is an interesting RNA virus that only infects hepatocytes that are already infected by hepatitis B. The HDV “borrows” the viral coat made by HBV to package its own nucleic acids. Acute hepatitis D infection occurs in two main settings: coinfection, where acute hepatitis B and D are transmitted together and infect the liver simultaneous, or superinfection, with HDV infecting a liver that already has chronic HBV infection. Those with superinfection tend to do worse, are more likely to develop chronic HDV infection, and are at greater risk for fibrosis progression and possibly for hepatocellular carcinoma. Those with acute coinfection of HBV and HDV tend to clear the infection (as do most adults with HBV monoinfection). Perinatal transmission of HDV is rare, and the most common transmission route is parenteral or sex.

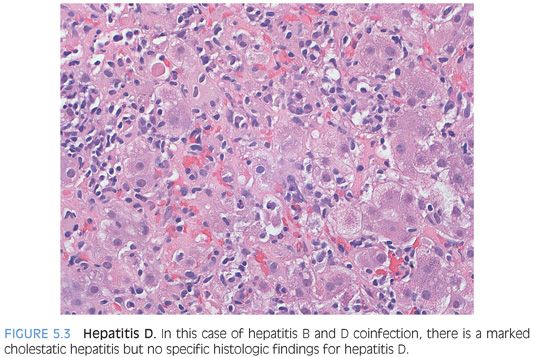

At the histologic level, there are no findings that are unique to HDV infection (Fig. 5.3). With coinfection, the biopsy typically shows moderate to marked acute lobular hepatitis, often with confluent or bridging necrosis. With superinfection, the biopsy will show typical changes of chronic hepatitis B, although the lobular activity tends to be moderate to marked in severity. The clinical findings of recent exposure to risk factors or an unexplained flare of hepatitis are the most important diagnostic clues. In a flare of chronic HBV, the HBV DNA levels are elevated above their baseline, whereas in a case of HDV superinfection, the increased liver enzymes are generally not accompanied by an increase in HBV viral DNA levels. In some parts of the South America, superinfection with HDV can be associated with acute liver failure. The biopsies show a microvesicular pattern of steatosis and in some cases are accompanied by numerous acidophil bodies (“extensive eosinophilic necrosis”).43–45

Immunostains for HDV are not available at most centers but can be very useful in making the diagnosis. In most cases, the diagnosis is made by testing serum for HDV RNA. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) or radioimmunoassay (RIA) testing for hepatitis delta antigen (HDAg) or testing for immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM antibodies to the HDV are available in referral laboratories. In general, testing for IgG or IgM antibodies are performed first, followed by confirmatory RNA testing of immunostaining.46 However, it is important to check current testing algorithms as they will evolve with time.

HEPATITIS C

Acute Hepatitis C

Acute hepatitis C is rarely biopsied because, in most cases, the acute infection has no or mild clinical symptoms. However, in the elderly, acute hepatitis C can be symptomatic and is occasionally biopsied.47 In this setting, the liver shows a cholestatic acute hepatitis with moderate to marked lobular inflammation and moderate lobular cholestasis.47 The portal tracts can show mild to moderate lymphocytic inflammation. In some cases of marked lobular hepatitis, the portal tracts will also show a ductular reaction, with proliferating bile ductules and with mixed portal inflammation. These changes can closely mimic biliary tract obstructive disease,47 but the present of the moderate to marked lobular inflammation will typically protect you from this diagnostic pitfall. In some cases, the histologic findings can resemble that of a drug reaction with bland lobular cholestasis and only very mild inflammatory changes.

Chronic Hepatitis C

Although most of the literature on chronic hepatitis C has come from the study of adult biopsies, the findings of chronic hepatitis C in children are essentially the same.48 Of note, children with perinatal acquisition of hepatitis C can have advanced fibrosis, despite a relatively short time of infection.

PORTAL TRACT FINDINGS. Chronic hepatitis C will typically show lymphocytic inflammation in the portal tracts and lobules. The inflammation in the portal tracts is typically mild (≈30% of cases) or moderate (≈65% of cases) and only occasionally marked (≈5% of cases).49 In most cases, there will be a somewhat diffuse portal chronic inflammation that is at least minimal in all portal tracts and may be moderate or marked in the medium-sized and larger portal tracts. Lymphoid aggregates may be present in the portal tracts, sometimes complete with germinal centers, but this finding is not specific for chronic hepatitis C and you should not overinterpret germinal centers as having any strong significance.

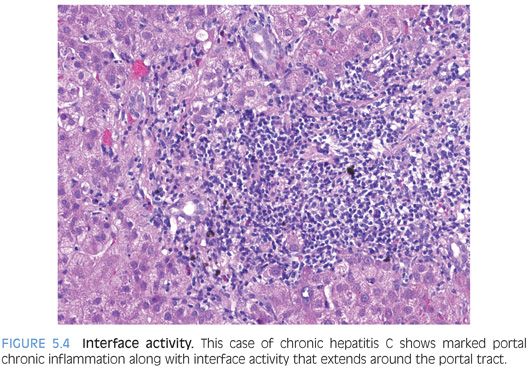

Interface activity is also common in livers with chronic hepatitis C (Fig. 5.4). Overall, the degree of interface activity tends to correlate strongest with the amount of portal chronic inflammation. Interface activity has received a great deal of attention over the years because it was an important part of an older classification of hepatitis that separated cases into “chronic active hepatitis” and “chronic persistent hepatitis.” This old classification system is no longer in use because it was neither very reproducible nor had clear clinically relevance, but the primary conceptual notion of a key role for interface activity in disease activity has persisted. Hepatitis C–infected hepatocytes are not localized to the portal/lobular interface, so interface activity does not directly reflect immune activity against virally infected hepatocytes—at least no more so than inflammation elsewhere in the lobules. Whether or not interface activity has greater clinical or biologic relevance than lobular inflammation or portal inflammation remains unclear from currently available data.