Chapter 7 ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

INTRODUCTION

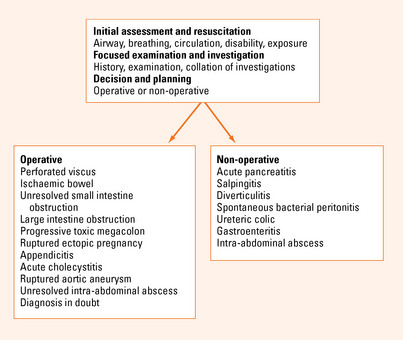

Acute abdominal pain should always be considered a surgical condition. The management of the patient with acute abdominal pain can be simplified by considering appropriate clinical management pathways and not focusing on the final diagnosis. The key to this is the use of clinical symptoms and signs in combination with limited special tests to decide if the patient is best treated by urgent or planned operation or conservative management. Many of these immediate decisions can be made by the bedside with a good history and examination.

CAUSES OF ACUTE ABDOMINAL PAIN

Generalised abdominal pain

Constant abdominal pain

In a patient with generalised constant abdominal pain and abdominal rigidity, the working diagnosis is peritonitis. This is always secondary to some other process. Often, but not always, this is due to a perforated viscus. The role of surgery is to provide peritoneal toilet and to prevent ongoing contamination by removing or repairing the perforated viscus. There are a number of conditions that fulfill this criterion. There are other conditions, however, that may demonstrate the signs of peritonitis but not require intervention (see Figure 7.1). Typically acute pancreatitis with generalised inflammation may have tenderness and guarding but does not require a laparotomy. A diagnostic elevated lipase may be very useful in this setting. In females, pelvic inflammatory disease may show generalised signs and does not benefit from laparotomy as there is no ongoing contamination. This should be considered in appropriate clinical contexts. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in portal hypertension should also be considered in patients presenting with generalised abdominal pain and portal hypertension with ascites.

Beware of the patient complaining of severe constant generalised abdominal pain who appears to have a relatively soft ‘doughy’ abdomen to palpation. This patient may have ischaemic bowel. Suspicion may be raised if they have bloody diarrhoea and atrial fibrillation. Investigations may reveal an elevated white cell count and a metabolic acidosis. Venous obstruction is often more subtle and slowly progressive.

Colicky abdominal pain

In contrast, a bowel obstruction will usually be associated with vomiting and constipation with progressive abdominal distension. The higher the obstruction is anatomically in the intestine, the earlier the vomiting and the later the constipation. The more distal the obstructing lesion, the greater the distension. A supine and erect plain abdominal film will usually confirm the diagnosis. An erect chest X-ray should always be ordered to look for free peritoneal gas. The supine abdominal film is the most useful. With the patient lying flat it will not show the fluid levels of the erect film but it will show gaseous distended bowel down to the level of obstruction. The ileum or small intestine can be distinguished by its central position and valvulae conniventes extending across the intestinal lumen. The jejunum or large intestine is distinguished by its incomplete valves and more peripheral position.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree