Acquired Anatomic Variations

Duodenal Diverticula

Duodenal diverticula are found in 1% to 6% of radiologic examinations and in an average of 8.6% of autopsies (147). They complicate peptic ulcer disease, choledocholithiasis (148), duodenal obstruction, and genetic or systemic disorders such as Marfan syndrome. Most duodenal diverticula develop as a result of chronic peptic ulcer disease (149). The ulcerating process causes fibrosis of the muscularis propria and abnormal contractility. Their frequency increases with

age; they rarely develop before age 40. The diverticula usually involve the second portion of the duodenum in a juxtapapillary location and are usually solitary and medial in location. Diverticula arise in weakened areas of the bowel wall that gradually balloon out, causing the diverticula to enlarge over time. The diverticular wall consists of variably inflamed mucosa and submucosa with only scattered muscle cells.

age; they rarely develop before age 40. The diverticula usually involve the second portion of the duodenum in a juxtapapillary location and are usually solitary and medial in location. Diverticula arise in weakened areas of the bowel wall that gradually balloon out, causing the diverticula to enlarge over time. The diverticular wall consists of variably inflamed mucosa and submucosa with only scattered muscle cells.

Jejunal and Ileal Diverticulosis

Jejunal diverticulosis is a heterogeneous disorder affecting 1.3% to 4.6% of the population (150). It consists of single or multiple diverticula predominantly involving the jejunum (Fig. 6.72). However, both the duodenum and the ileum may be involved (150). Jejunal diverticula develop seven times more commonly than ileal diverticula (151); men are affected twice as frequently as women. Most affected individuals are over age 40 (150); 82% of patients remain asymptomatic. The diverticula become evident as an incidental finding at the time of surgery, autopsy, or radiographic examination. Neuromuscular disorders typically coexist with jejunal diverticulosis, including Fabry disease, visceral myopathies or neuropathies, scleroderma, and neuronal inclusion disease (150). As a result, patients often suffer from pseudo-obstruction or malabsorption secondary to bacterial overgrowth. Diverticular resection cures the malabsorption. Small intestinal diverticula perforate, bleed, become inflamed, and undergo other complications. These complications lead to morbidity and mortality rates as high as 40%.

Small intestinal diverticula begin as a pair of small outpouchings along the mesenteric border. The mucosa herniates through the muscle layer along the path of the penetrating vessels. Alternatively, localized areas of muscular fibrosis and atrophy may weaken the bowel wall, creating localized mural sacculations. Uncoordinated muscular contractions from an underlying motility disorder lead to focal areas of increased intraluminal pressure and mucosal herniation through the weakened areas. The pair of outpouchings then enlarges until the outpouchings meet and they may fuse in the line of the mesentery, thereby forming a single thin-walled diverticulum. The diverticula usually measure <1 cm in size, although they may be larger. Jejunal diverticula tend to be larger in the proximal jejunum and become smaller and fewer as one progresses distally in the GI tract. As many as 400 diverticula ranging in size from 1 to 22 cm in diameter can exist in a single patient (150).

Histologically, diverticula are lined by mucosa, muscularis mucosae, and submucosa, but they usually lack a muscularis propria. The mucosa usually shows some degree of crypt hyperplasia, villous atrophy, and chronic inflammation, probably resulting from intestinal stasis and bacterial overgrowth. Lipid-containing histiocytes often lie in the mucosa, in the submucosa, and along lymphatics close to the collar of muscularis propria surrounding the diverticular neck (152). The histology of the bowel wall sometimes shows an underlying myopathy or neuropathy (see Chapter 10) or only fibrosis of the muscularis propria (150).

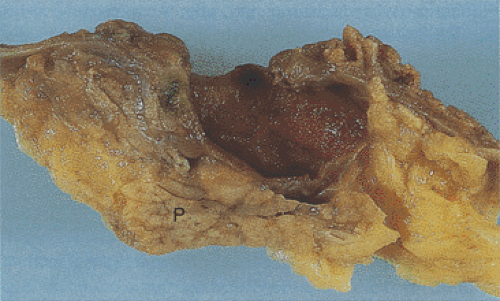

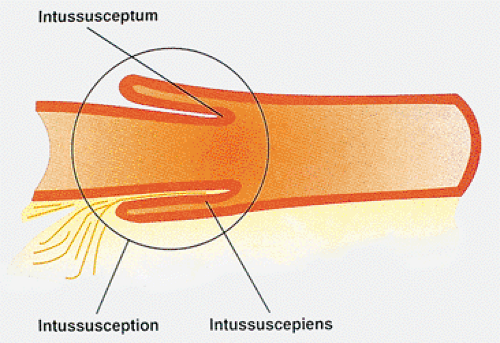

Intussusception

An intussusception results from invagination of an intestinal segment (the intussusceptum) into the next part of the intestine that forms a sheath around it (the intussuscipiens) (Figs. 6.73, 6.74, 6.75, and 6.76). Intussusceptions are classified as primary (without an identifiable cause) or secondary (due to a pre-existing lesion). They are one of the most common abdominal emergencies in early childhood. Two thirds of cases occur in infancy, with a peak incidence between 3 and 5 months of age (153,154). Intussusception is the most common cause of intestinal obstruction in children (155,156), affecting 1.5 to 3.8 cases per 1,000 live births a year. The incidence varies considerably in different parts of the world (157). Some patients have strong family histories of intussusception (158). Paradoxically, there appears to be a high incidence of intussusception in doctors’ families (159). In the United States, there is a male predominance of 2:1 and a seasonal prevalence with two peaks, one in the winter and one in the summer (160). Patients are typically well nourished, without a history of gastrointestinal disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree