Acquired Abnormalities

Diverticular Disease

Etiology

Colonic diverticular disease has become increasingly prevalent in the United States and other economically developed countries. Its incidence varies with national origin, cultural background, and diet, and its frequency increases with advancing age. In Western societies, it affects approximately 5% to 10% of the population over 45 years old and almost 80% of those over age 85 (37). The increased incidence of diverticular disease seen in Japan (38), South Africa (39), and Israel (40) in the last few decades results from incorporation of Western-type foods into the diet in these geographic regions.

Three major forms of diverticular disease exist: (a) one that is associated with classic intestinal muscle abnormalities; (b) a form that complicates connective tissue diseases (41); and (c) forms that complicate neural abnormalities (41). In the most common form of the disease, aging; elevated colonic intraluminal pressure; decreased dietary fiber consumption; consumption of beef, beef fat, and salt; lack of physical activity; and the presence of constipation correlate with its development (42,43). The prevalence of diverticular disease in Western countries increased abruptly 30 years after the introduction of grain milling factories, which decreased the fiber content in grain (44). Decreased luminal fiber and lower stool volume require more colonic segmentation to propel feces forward. The increased segmentation generates greater intraluminal pressures predisposing to diverticula formation. The colonic wall is weakest where penetrating arteries pierce the muscularis propria; this is where the diverticula typically form. Genetic factors may also play a role in the development of diverticular disease since diverticula

arise in the right colon in Asians (45) and young patients, contrasting with sigmoid and left colonic involvement among Occidentals and older individuals (46,47). Alternatively, right-sided diverticulosis is a different disease than left-sided predominant diverticulosis. Some patients with solitary rectal diverticula have scleroderma (48). Children with colonic diverticulosis often have underlying Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or an association with polycystic kidney disease (49).

arise in the right colon in Asians (45) and young patients, contrasting with sigmoid and left colonic involvement among Occidentals and older individuals (46,47). Alternatively, right-sided diverticulosis is a different disease than left-sided predominant diverticulosis. Some patients with solitary rectal diverticula have scleroderma (48). Children with colonic diverticulosis often have underlying Marfan or Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or an association with polycystic kidney disease (49).

Clinical Features

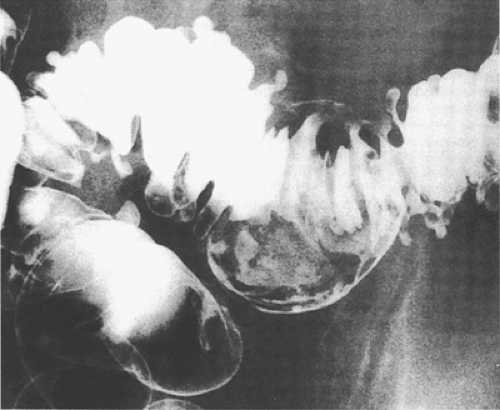

Most people with diverticulosis remain asymptomatic, only to be diagnosed incidentally (Fig. 13.26). Ten to twenty-five percent of patients become symptomatic (49), usually due to development of diverticular inflammation (diverticulitis). Diverticulosis affects both sexes equally (45), although complicated diverticulosis more frequently affects obese males (50). Children with diverticulosis often have an underlying connective tissue disease or polycystic renal disease (49). Acute diverticulitis varies in severity. Clinical features include lower abdominal pain, made worse by defecation, and signs of peritoneal irritation, including muscle spasm, guarding, rebound tenderness, fever, and leukocytosis. Symptom duration may be short and rectal examination may reveal the presence of a tender mass. Patients developing diverticulitis at an early age appear to have a more virulent form of the disease than other individuals (50).

FIG. 13.26. Diverticulosis. Double-contrast barium enema demonstrates numerous small outpouchings representing colonic diverticula. |

Rectal bleeding, usually microscopic, affects 25% of patients. Significant bleeding occurs in 3% to 5%. Diverticular bleeding can be sudden in onset, painless, massive, and not accompanied by signs or symptoms of diverticulitis. Bleeding is more common in patients with diverticulosis complicating an underlying connective tissue disease. Although most diverticula arise on the left side, most diverticular bleeds complicate right-sided diverticula (51). The reason for this is unclear. One explanation may be that right-sided diverticula have wider necks than left-sided ones (51). The blood appears bright red, maroon, or melanic, especially if it comes from the right colon. Bleeding most often occurs from a single diverticulum and it stops spontaneously in 80% to 90% of patients (52). Some patients develop recurrent, left lower quadrant, colicky pain without clinical or pathologic evidence of acute diverticulitis. Alternating bouts of constipation and diarrhea result from muscle spasm. Most patients have elevated white blood cell counts, erythrocyte sedimentation rates, and C-reactive protein. When diverticulitis develops, the clinical features reflect host defenses and bacterial virulence.

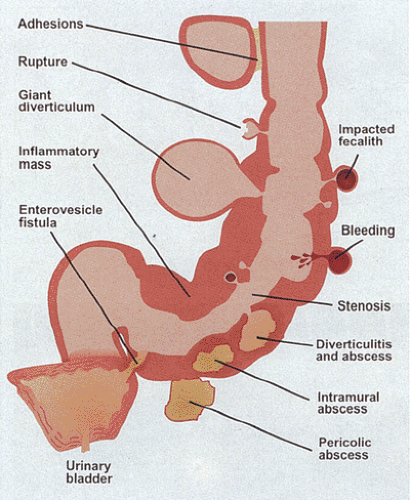

Complications of diverticular disease are shown in Figure 13.27. They are more common among individuals ingesting nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (53), perhaps

because the drugs mask the symptoms of earlier disease or because the NSAIDs interfere with natural mucosal defenses. Life-threatening complications are more common among patients with chronic renal failure or on high-dose steroid therapy (54,55). Complications include bleeding, perforation, fistula formation, peritonitis, obstruction, and peridiverticular abscesses. Fistulae complicate transmural inflammation. When fistulae develop, diverticular disease resembles Crohn disease (CD). Pseudodiverticula result from partial drainage of an abscess cavity into the colon. Patients may die from recurrent pericolic abscesses, peritonitis, fecal peritonitis, bleeding, or bowel obstruction (56).

because the drugs mask the symptoms of earlier disease or because the NSAIDs interfere with natural mucosal defenses. Life-threatening complications are more common among patients with chronic renal failure or on high-dose steroid therapy (54,55). Complications include bleeding, perforation, fistula formation, peritonitis, obstruction, and peridiverticular abscesses. Fistulae complicate transmural inflammation. When fistulae develop, diverticular disease resembles Crohn disease (CD). Pseudodiverticula result from partial drainage of an abscess cavity into the colon. Patients may die from recurrent pericolic abscesses, peritonitis, fecal peritonitis, bleeding, or bowel obstruction (56).

Giant colonic diverticula are rare complications of diverticular disease. They are characterized by the formation of large, unilocular, gas-filled cysts measuring 7 cm or more in diameter (Fig. 13.28). Rare lesions measure over 27 cm in diameter. Giant diverticula typically develop on the mesenteric border of the sigmoid colon. Patients range in age from their mid-30s to their 80s. The lesions mimic enterogenous cysts (57).

Barium enema often establishes the diagnosis of diverticulosis. Early changes consist of the presence of fine mural serrations known as the prediverticular state or myochosis. “Saw tooth” luminal irregularities reflect associated muscle spasm. A contracted haustral pattern may also be seen. The sigmoid becomes shortened and distorted, causing it to acquire a concertinalike appearance with bunched, redundant mucosal folds. These can significantly narrow the colonic lumen and may cause obstruction with dilation proximal to the area of obstruction.

Pathologic Features

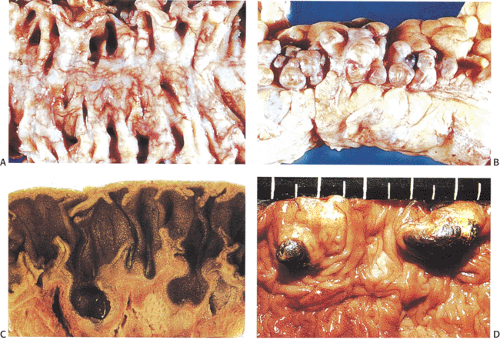

Diverticula are flask-shaped mucosal outpouchings that develop anywhere in the colon. In the Western world, 90% of patients have involvement of the sigmoid colon and 20% of patients have pancolonic involvement. In contrast, Asians with diverticular disease develop multiple diverticula in the right colon (45). Diverticula usually form where the penetrating arteries pierce the muscular wall. Because the penetrating arteries enter on the mesenteric side of the two lateral taeniae coli, diverticula commonly appear as two parallel rows of beaded outpouchings along the bowel wall (Fig. 13.29). Appendices epiploicae also lie in this location and they may cover diverticula beneath them. The presence of pronounced muscular hypertrophy provides a clue to the presence of the diverticula, since the muscle thickening is the most consistent and striking abnormality. The taeniae coli appear thickened, developing an almost cartilaginous quality; the circular muscle becomes corrugated (Figs. 13.30 and 13.31) (58). The mouths of the diverticula lie between the muscular corrugations as they penetrate the muscularis propria (Fig. 13.32).

Because the diverticula often lack the muscular layer, secretions and fecal material easily enter them where they accumulate because they cannot be expelled (Fig. 13.29). Feces in the diverticular orifice block the outflow of secretions. The resulting obstruction and ulceration (with bacterial invasion) leads to diverticulitis via mechanisms resembling those seen in appendicitis (see Chapter 8). Mucosal ulceration by a fecalith leads to infection, diverticulitis, and bleeding.

Bleeding usually comes from uninflamed diverticula (Fig. 13.33) and the exact bleeding point is often difficult to identify. Occasionally, one is lucky enough to see a bleeding point or to obtain a histologic section through a diverticulum that identifies the bleeding source. Arteriolar rupture involves small vessels measuring <1 mm in diameter and always occurs on the side of the vessel facing the bowel lumen (Fig. 13.34) (59). The colonic wall may be thickened by pericolonic fibrosis, grossly simulating a neoplasm or inflammatory bowel disease.

Tonic muscular contractions produce redundant, accordionlike, mucosal folds (Fig. 13.35), which appear as exaggerations of the mucosal folds or as larger, leaflike, smooth-surfaced “polyps” with broad bases (60). When multiple, they form two rows between the diverticula. Repeated trauma to the folds causes mucosal erosion and bleeding.

Colonoscopic examination in patients with diverticulosis-associated colitis shows confluent granularity and friability affecting the sigmoid colon surrounding the diverticular ostia. The colonic mucosa proximal and distal to the area of diverticulosis appears endoscopically normal. Not uncommonly, a diagnosis of Crohn disease is entertained due to the segmental nature of the colonoscopic findings. The biopsy can often be differentiated between the two entities if the pathologist is made aware of the presence of diverticulosis in the segment of interest.

The histologic features depend on whether one is dealing with simple diverticulosis or with its complications. The major pathologic features of uncomplicated diverticulosis

include a thickened muscularis propria and the diverticular outpouchings (Fig. 13.32), usually lined by mucosa, muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and variable amounts of muscularis propria (Figs. 13.31 and 13.32). Early diverticula may still possess an outer lining of attenuated muscle. This disappears as the diverticula extend beyond the colonic wall. The mucosa appears normal or may show marked chronic inflammation, with or without acute inflammation producing a pattern sometimes referred to as “isolated sigmoiditis” (Fig. 13.36). Trauma within a diverticulum may induce asymmetric intimal proliferations and scarring of the associated vessels, predisposing them to rupture and bleeding (59). The arterial wall exhibits duplication of the internal elastic lamina and eccentric medial thinning, especially on its luminal side (Fig. 13.34). Some have suggested that the thick-walled vessels are angiodysplastic and that there is an association between angiodysplasia and diverticular disease (61). The myenteric plexus may become abnormal and disorganized (Fig. 13.37), a change leading to secondary motility disturbances.

include a thickened muscularis propria and the diverticular outpouchings (Fig. 13.32), usually lined by mucosa, muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and variable amounts of muscularis propria (Figs. 13.31 and 13.32). Early diverticula may still possess an outer lining of attenuated muscle. This disappears as the diverticula extend beyond the colonic wall. The mucosa appears normal or may show marked chronic inflammation, with or without acute inflammation producing a pattern sometimes referred to as “isolated sigmoiditis” (Fig. 13.36). Trauma within a diverticulum may induce asymmetric intimal proliferations and scarring of the associated vessels, predisposing them to rupture and bleeding (59). The arterial wall exhibits duplication of the internal elastic lamina and eccentric medial thinning, especially on its luminal side (Fig. 13.34). Some have suggested that the thick-walled vessels are angiodysplastic and that there is an association between angiodysplasia and diverticular disease (61). The myenteric plexus may become abnormal and disorganized (Fig. 13.37), a change leading to secondary motility disturbances.

FIG. 13.29. Colonic diverticulosis. A: Opened bowel. Two parallel rows of numerous diverticular openings are easily visualized. B: The serosal aspect of the specimen in A. Numerous diverticular outpouchings are present. Their relationship with the appendices epiploica is also seen. C: Cross section of diverticulosis demonstrating the flasklike outpouchings extending into the colonic fat. D: Luminal surface showing two diverticula filled with feces.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|