24 Abnormal liver function test results

Case

A 45-year-old male was found to have abnormal liver function tests on routine investigations performed for an insurance examination. Serum alanine aminotransferase level was elevated at 105 IU/L. International Normalized Ratio (INR), albumin and bilirubin were normal. The patient also had a history of hypertension controlled on antihypertensive therapy and an elevated fasting serum triglyceride concentration. His father had type 2 diabetes, but there was no family history of liver disease. An abdominal ultrasound examination demonstrated changes consistent with fatty liver, but no other abnormality. Further investigations showed no evidence of autoimmune, viral or inherited liver disease. His ferritin was mildly elevated, but with normal transferrin saturation and no mutation of the haemochromatosis (HFE) gene. Physical examination revealed him to be overweight, but otherwise was unremarkable. The patient was advised to reduce his weight and exercise regularly. Under the guidance of a dietician a 5% weight loss was achieved with an improvement in alanine aminotransferase levels. Following that he failed to maintain the intervention, gained weight and discontinued medical review. Ten years later he again was found to have abnormal liver tests but also INR 1.6, albumin 28 gm/L and bilirubin 25 μg/L. He had become diabetic with symptomatic ischaemic heart disease. Abdominal ultrasound on this occasion showed a small irregular liver with splenomegaly, consistent with cirrhosis and an apparent mass in the liver. On a triple phase computed tomography (CT) scan of the liver, the 2-cm mass lesion was typical of a hepatocellular carcinoma and was managed surgically.

An Approach to the Patient with Liver Disease

Liver disease will present as one of a limited number of clinical syndromes. Each syndrome may be caused by a number of specific disease processes. A diagnosis is achieved by paying attention to historical features and physical findings (Box 24.1) and the results of laboratory and other investigations. Only then can specific treatment for the cause of the liver abnormality be planned. Therapy, in many instances, is directed to the management of the clinical problem in addition to treatment directed to the underlying condition.

Box 24.1 Symptoms and signs of liver disease

Signs of poor hepatocellular synthetic function

Bruising, peripheral oedema (reflecting depleted coagulation factors and albumin levels)

Signs of end-stage liver disease

Wasting, progressive severe fatigue, encephalopathy (asterixis, fetor, coma)

In this chapter, liver function tests and their clinical relevance are discussed first because abnormalities are commonly detected in asymptomatic individuals. Next, the common clinical presentations of liver disease are covered. Finally, important liver diseases are described.

Liver Function Test Interpretation

Bilirubin

Elevated serum bilirubin levels may occur in all forms of liver disease. However, it must be remembered that a jaundiced patient does not necessarily have significant hepatic disease. Serum levels of bilirubin reflect production, hepatic uptake, processing (conjugation) and secretion. The physiology of bilirubin and an approach to diagnosis and management of jaundice is described in Chapter 23.

Tests reflecting hepatic function

Serum albumin

In chronic liver disease, low serum albumin concentrations represent a major prognostic indicator (see ‘Child-Pugh score’ later in this chapter). This can reflect the absence of sufficient functioning hepatocytes to maintain albumin production. Furthermore, malnutrition can be a significant contributor to hypoalbuminaemia in patients with chronic liver disease. Alcohol consumption can reduce albumin synthesis. Serum albumin concentrations may also fall without a reduction in hepatic synthesis when the volume of distribution of albumin is expanded by ascites and oedema. As albumin has a half-life of 17–26 days, low levels usually reflect chronic rather than acute hepatitic dysfunction.

Tests of Liver Injury

Transaminases

In the presence of malignant disease, increases in transaminases often indicate hepatic metastases.

Aspartate aminotransferase

Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) is an enzyme found in liver, skeletal muscle, myocardium, kidney, pancreas and erythrocytes. Damage to any of these cell types will result in an elevation of serum AST. ALT levels are usually higher than AST levels in viral liver injury. When liver disease is present, and the AST level is more than twice that of ALT, alcoholic liver disease must be considered (see later). In the presence of cirrhosis, the diagnostic value of the AST:ALT ratio is lost. The mitochondrial isoenzyme of AST is especially elevated in the presence of alcoholic liver injury.

Cholestasis versus hepatocellular disease

Liver function patterns may be used to guide the discrimination between cholestasis (e.g. due to stones or tumour obstructing the large bile ducts) and hepatocellular disease (e.g. cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis). These patterns can be used only as a broad guide and should not be relied on alone. However, if cholestasis is suspected, then looking for evidence of duct obstruction (e.g. by ultrasound) is the next step, while if hepatocellular disease is suspected, then a search for liver disease markers (e.g. virology, immunological tests) is the next step (see Table 23.1 in Ch 23).

Other tests useful in hepatic assessment

A marked elevation (over 1000 U/L) of alpha-fetoprotein is most often due to hepatocellular carcinoma. This test has been used for screening an individual with chronic hepatitis B for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma, having a sensitivity of 70%. It is of limited value, however, because the sensitivity falls to 30% in non-hepatitis B hepatocellular carcinoma. Milder elevations occur in both acute and chronic liver disease of many causes (Ch 25).

Autoantibodies are helpful in diagnosing certain forms of liver disease (Table 24.1). Serum concentration of caeruloplasmin and iron studies are important tools in the diagnosis of Wilson’s disease and haemochromatosis, respectively (Table 24.2), but are also altered by liver injury unrelated to either of these conditions. Tests for viral hepatitis are also important (Table 24.3).

Table 24.1 Tests for autoimmune liver disease

| Test | Condition | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Antinuclear antibody (ANA) | Autoimmune chronic hepatitis | Diagnosis requires liver biopsy |

| Smooth muscle antibody (SMA) (anti-actin) | Autoimmune chronic hepatitis | Diagnosis requires liver biopsy |

| Anti-liver kidney microsomal antibody (anti-LKM1) | Autoimmune chronic hepatitis | Diagnosis requires liver biopsy |

| Antimitochondrial antibody (AMA) | Primary biliary cirrhosis(95%) | Diagnosis requires liver biopsy |

| Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) | Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Diagnosis requires magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

Table 24.2 Tests for metabolic disorders affecting the liver

| Test | Condition | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Iron studies | Haemochromatosis | See text |

| Copper and caeruloplasmin | Wilson’s disease | See text |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin level and phenotype | Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | Heterozygotes may have abnormal liver function tests without significant liver disease |

| Thyroid function tests | Hypothyroidism | Fatty liver |

| Blood glucose level | Diabetes mellitus | Fatty liver, haemochromatosis |

| Insulin/C-peptide | Insulin resistance | Fatty liver, metabolic syndrome |

| Cholesterol and triglycerides | Primary and secondary hyperlipidaemia | Fatty liver, alcoholic liver disease |

Table 24.3 Tests for viral hepatitis

| Test | Meaning of a positive result | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tests for hepatitis A virus (HAV) | ||

| Anti-HAV IgM | Recent acquisition of HAV | Acute hepatic illness likely to be HAV |

| Anti-HAV IgG | Past infection/vaccination | Immunity |

| 2. Tests for hepatitis B virus (HBV) | ||

| HBsAg (surface ag) | Present/chronic infection | Structural component of virus |

| Anti-HBsAg (surface ab) | Past infection/vaccination | Immunity |

| Anti-HBc IgM (core ab) | Recent acquisition of HBV | The test for acute HBV infection |

| HBeAg (e ag) | Marker of viral replication | High risk of infectivity |

| Anti-HBeAg (e ab) | Suggests no viral replication | Unlikely to be infectious |

| HBV DNA | Presence of complete virus | High risk of infectivity |

| 3. Tests for hepatitis C virus (HCV) | ||

| Anti-HCV | Exposure to HCV | Interpret in conjunction with other clinical and laboratory data |

| HCV RNA by PCR | Presence of virus | – |

| HCV genotyping | – | Treatment planning and response |

| 4. Tests for hepatitis D virus (HDV) | ||

| Anti-HDV IgG/IgM | Exposure to HDV | Acute or chronic HDV |

| Delta antigen | HDV present | Acute or chronic HDV |

| 5. Tests for hepatitis E virus (HEV) | ||

| Anti-HEV IgM | Recent acquisition of HEV | Acute hepatitic illness likely to be HEV |

| 6. Tests for other organisms | ||

| Cytomegalovirus (CMV) IgM | Recent acquisition of CMV | Acute hepatitic illness likely to be CMV |

| Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) IgM | Recent acquisition of EBV | Acute hepatitic illness likely to be EBV |

| Anti-HIV | HIV-AIDS | Opportunistic hepatobiliary infections |

| Toxoplasmosis serology | – | Consider toxoplasmosis |

| Q fever serology | – | Consider Q fever |

ag = antigen; ab = antibody; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

Liver biopsy

Histological and, on occasion, chemical analysis and microbiological examination of the liver are essential in the diagnosis of many hepatic disorders. The usual technique for obtaining a liver biopsy involves a percutaneous approach through a lower intercostal space in the right midaxillary line. Ultrasound scanning or CT can be used to optimise the needle entry point or target specific abnormalities. Haemorrhage from the biopsy wound to the liver or injury to adjacent organs are the major risks. These may be significant in approximately 1% of biopsies. The risk of haemorrhage is minimised by ensuring a platelet count greater than 80 × 109/L (80,000/mm3) and an INR less than 1.2. When coagulopathy or gross ascites prevents a percutaneous biopsy, a transjugular approach can be used.

The significance of liver biopsy features is considered in relation to specific disorders later in this chapter. The extent, nature and activity of inflammatory and fibrotic processes are of particular concern. The presence of fibro-inflammatory changes is more likely to be related to a progression to cirrhosis. The absence of such changes carries a better prognosis. Sampling error can be a problem as the tissue sample represents only a tiny proportion of the liver mass and the disease process may not be uniform across the organ. Cirrhosis can be missed in 10–20% of cases, depending on the size and number of samples taken.

The Well Patient with Abnormal Liver Function Profile

History

A history of diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease and high lipid levels should be sought; these together with obesity are associated with hepatic steatosis. The features of the metabolic syndrome with rising body weight and reduced physical activity are common in those with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, especially when there is a family history of type 2 diabetes.

There is a possibility of genetic predisposition to alcoholic liver disease.

In the otherwise well patient, a history of abdominal pain (e.g. biliary pain: Ch 4), loss of appetite or weight (Ch 17), or a change in the colour of stools or urine (Ch 23) needs to be sought but is almost invariably absent.

Examination

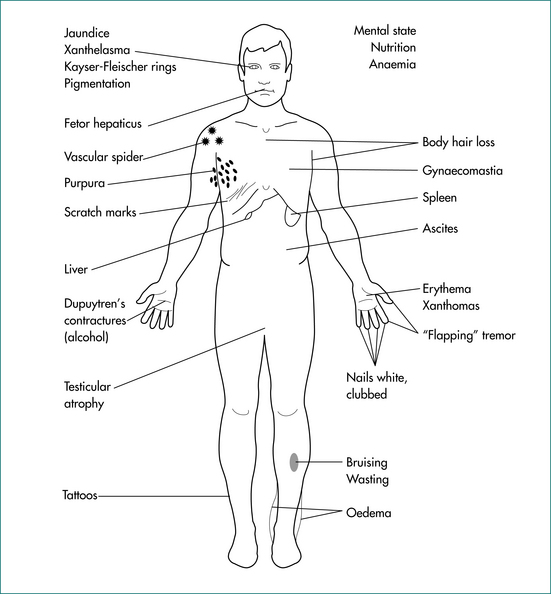

Patients with abnormal liver test results must be regarded as having a liver disorder and thus signs of chronic liver disease should be sought because cirrhosis may be completely asymptomatic (Fig 24.1). The patient’s weight and height should be measured during the examination to allow evaluation of the body mass index (weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres: kg/m2). Truncal obesity is common and waist measurement should be taken.

Figure 24.1 Signs of chronic liver disease.

From Sherlock S, Dooley J. Diseases of the liver and biliary system. 11th edn. Oxford: Blackwell; 2002, with permission.

In the usual patient presenting with no history of symptoms and no awareness of liver problems, it is likely that there will be no signs of liver disease. A minor degree of hepatomegaly should be expected in patients with alcohol-related fatty liver or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (Ch 17). Mild splenomegaly may also be found.

Investigation

Liver imaging is of value (Ch 23). Abdominal ultrasound scans can provide information about the size and shape of the liver and spleen. Often any mass lesions present can also be identified. Ultrasonography will often detect fatty liver. Abdominal CT will provide information on the presence or absence of space-occupying lesions while, in addition, providing insight into liver density, which may be increased in haemochromatosis. Magnetic resonance imaging will usually add little to the information provided by a CT scan but can be of value in certain circumstances, such as in the assessment of mass lesions and of the biliary tract.

Tests for evidence of viral hepatitis (Table 24.3), autoimmune liver disease (Table 24.1) and other causes of chronic liver disease (iron or copper overload, and other inherited liver diseases) (Table 24.2) should be done if hepatocellular disease is possible. If the diagnosis remains unclear and the prognosis of concern, a liver biopsy is required.

Chronic hepatitis is an ongoing inflammatory process. The causes are listed in Table 24.4. If fibrosis follows as part of the healing process consequent to this inflammation, progression to cirrhosis and eventual liver failure is possible. For this reason, potentially controllable chronic hepatitis needs to be identified and treated before irreversible injury has occurred.

Table 24.4 Important causes of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis

| Chronic hepatitis | Cirrhosis |

|---|---|

Evidence of continuing hepatic inflammation based on a persistent elevation of serum transaminases (6 months or more) is usually required to entertain the diagnosis of a chronic hepatitis. However, it can take many months for serum transaminases to return to normal levels following some acute hepatic illnesses. Once the presence of chronic hepatitis is considered likely, establish the aetiology of the illness, the extent of liver damage and the activity of the inflammatory process. These latter two features can be assessed only by the histological examination of a liver biopsy.

The Sick Patient with Jaundice: Acute Liver Disease

Acute hepatitis

Examination

The patient can appear relatively well or profoundly ill. Jaundice may or may not be present. The liver size is noted. It will often be enlarged and tender. There may be splenomegaly. Look for evidence of an underlying condition (e.g. signs of alcohol excess). Complications (e.g. hepatic encephalopathy) may supervene. Look for signs of chronic liver disease (Fig 24.1).

Investigation

Serum transaminase levels are elevated, usually more than five times the upper limit of normal. In viral hepatitis, transaminase levels of 1000 U/L and over are not unusual. Moderate elevations of alkaline phosphatase also occur. Serum albumin and INR usually remain normal. Specific blood tests are required to diagnose viral illnesses, including viral hepatitis (A, B, C, D and E), cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus, toxoplasmosis, Q fever and autoimmune disease (Table 24.3). Paracetamol levels should be determined and laboratory evidence of alcohol excess sought. These may be relatively low in patients with chronic, but toxic paracetamol consumption. Abdominal ultrasound scans are useful to document the size of the liver and spleen and to exclude biliary disease.

Management

Alcoholic hepatitis is managed supportively; in certain circumstances specific interventions may be of value. Ethanol is withdrawn, and vitamin (especially thiamine) and nutritional supplementation should be given (enteral feeding may provide a survival benefit). Corticosteroids (prednisone, 40 mg daily for 28 days) may provide a survival benefit when there is encephalopathy (see below) and no gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Propylthiouracil may be of benefit in less severe cases of alcoholic hepatitis, but is rarely used. Abstinence remains the mainstay of therapy.

When gallstone disease is found to be the cause of an acute hepatitic illness, cholecystectomy may be indicated. Choledocholithiasis may require endoscopic clearance of the bile duct (Ch 23). Acute autoimmune hepatitis is managed with corticosteroids (e.g. prednisone, 30–60 mg daily, then taper).

Acute Liver Failure

Assessment and management

Examination is directed towards assessing the possible aetiology and evolving complications of hepatic failure (outlined below). Serial liver function tests can be useful, but a falling ALT level may reflect either recovery or progression to massive hepatic necrosis. A temperature above 38°C or below 36°C, a pulse rate above 90 beats per minute and/or a white cell count above 12,000 or below 4,000 are associated with a greater mortality. The prognosis, and therefore need for liver transplantation, of a patient in acute liver failure can be assessed using the Kings College Criteria (Table 24.5).

Table 24.5 Kings College Criteria for listing of a patient in acute liver failure (ALF) for liver transplantation

| Type | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Paracetamol-induced ALF | Arterial pH < 7.30 after fluid resuscitation or all of: |

| Non-paracetamol-induced ALF | INR > 6.5 or any three of: |

INR = International Normalized Ratio.

From O’Grady JG, Alexander GJM, et al. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology 1989; 97:439–445.

The patient with fulminant hepatic failure needs to be admitted directly to a unit capable of offering liver transplantation. Admission to intensive care is required with careful management of cerebral oedema, gastrointestinal bleeding, infection and renal failure.

Prognosis

Liver transplantation is a therapeutic option. The decision to transplant and the timing of transplantation are difficult. However, 1-year survival rates of approximately 70% can be achieved. This compares favourably with mortality rates from fulminant hepatic failure without transplantation of up to 90% although with optimal intensive care unit management 30–40% survival can be achieved. N-acetylcysteine may also improve overall survival and transplant-free survival in patients with non-paracetamol-related acute liver failure, especially if encephalopathy is limited to grade I or II.

Patients Presenting with Cirrhosis and its Complications

Cirrhosis represents the non-specific end-stage of hepatic disease that has disrupted the structural organisation of the liver. The presence of cirrhosis is established on a liver biopsy. Fibrosis or scarring surrounding regenerative nodules of hepatocytes is its hallmark. Although cirrhosis is a histological diagnosis, its presence is clinically suspected by finding signs of chronic liver disease and portal hypertension (Box 24.1) or on high quality imaging. Symptomatic liver disease and eventually liver failure occur as the result of impaired hepatocellular function within the distorted architecture of the regenerative nodules and, with progression, eventual loss of an effective liver cell mass. Distortion of the hepatic circulation contributes to portal hypertension and inefficient/ineffective perfusion of parenchymal cells. Portal systemic shunts may develop, allowing blood from the gastrointestinal tract to flow directly to the systemic circulation.

Cirrhosis should be considered as either compensated, with no signs of complications and a relatively good prognosis, or decompensated (Ch 25). Those with compensated cirrhosis are likely to be asymptomatic and the diagnosis may be made incidentally during the investigation of an unrelated condition. In this situation, counselling regarding diet, ethanol consumption and the identification and management of any underlying treatable condition are warranted (see ‘The well patient with abnormal liver function profile’ above). Recent data have indicated that the removal or cure of the underlying disease process can be followed by a reduction in hepatic fibrosis (e.g. after the cure of hepatitis C).

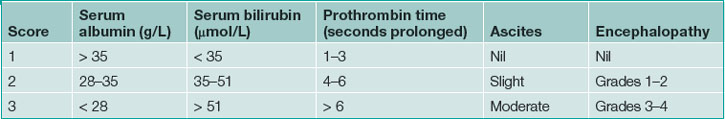

The Child-Pugh score (Table 24.6) provides a useful means of assessing the severity of cirrhosis and the prognosis. A Child-Pugh ‘A’ classification applies to a score of less than 7; ‘B’, a score between 7 and 9; and ‘C’, greater than 9. The 1-year survival of these classification groups is 100%, 80% and 45%, respectively. A higher score also indicates those more likely to succumb to complications during hepatic and no hepatic surgical procedures.

The MELD (Model for End Stage Liver Disease) score is a validated means of assessing the prognosis and survival of a patient with chronic liver disease that incorporates bilirubin, INR and creatinine values. This score can be used to prioritise the allocation of organs within a liver transplantation program (see Ch 25).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree