26 Abdominal incidentalomas

Case

Mrs AI, a slim, previously well 65-year-old woman presented to her general practitioner with dysuria. There was a trace of blood in her urine and erythrocytes were seen on urine microscopy, so a renal ultrasound scan was carried out. This did not detect any renal abnormality, but did reveal a 1-cm solitary, mobile gallstone in an otherwise normal, thin-walled gallbladder. A complete ultrasound scan assessment of the liver, biliary tree and pancreas was carried out and no other pathology was identified; in particular, there was no evidence of choledocholithiasis. Following first principles, her doctor first of all revisited her medical history and found no symptoms other than the dysuria and in particular no biliary symptoms. No abnormality was detected on physical examination, in particular no biliary signs. Her liver function tests were normal.

Diagnosis and Management

In women, unexpected pelvic mass lesions are common. However, these are not covered here. Dystrophic calcification (normal serum calcium, abnormal tissue) is a very common incidental finding on abdominal imaging. Dystrophic calcification is often seen in malignancies but is most commonly due to age-related degeneration or inflammation and scarring and will not be treated as an incidental mass in the context of this chapter.

The investigation plan

The investigation of incidentalomas is a two-stage process. The first stage is non-invasive and includes a thorough review of the clinical history and examination with particular focus on the organ systems and the most likely disease processes (see Box 26.1). Disease risk factors and symptom patterns may suggest a particular diagnosis or disease process and may help focus the diagnostic plan. A thorough physical examination, including a careful and complete examination outside the system involved looking for signs of primary or secondary involvement elsewhere, may similarly shorten the time to diagnosis.

Box 26.1 Investigation of an incidental, scan-detected abdominal mass. Stage 1: non-invasive investigations

It will not always be necessary to proceed to the second stage, that of invasive investigations (Box 26.2). The indications for this and the pattern of investigations chosen in stage 2 will depend on the findings from the non-invasive investigations of stage 1. Invasive or physiologically disruptive diagnostic procedures may include imaging guided biopsies, arteriography, barium enema, endoscopic procedures and associated biopsies or, less frequently, diagnostic laparoscopic or open surgery. All invasive investigations incur some risk, discomfort and expense. The patient must be fully informed about this and must be able to comply with the requirements of the investigation. Hence, a patient who cannot remain still may not be suitable for a percutaneous biopsy. A patient who suffers from claustrophobia may not be suitable for an MRI scan.

Biliary Incidentalomas

Asymptomatic gallstones

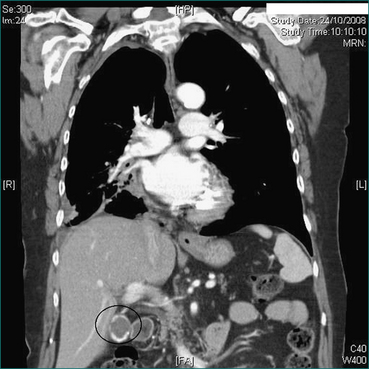

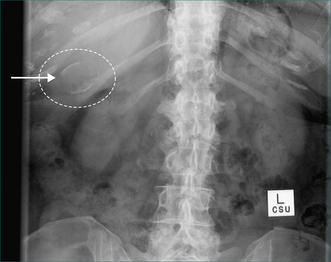

Prophylactic cholecystectomy may be justifiable for gallstones larger than 2.5 cm; the risk of acute cholecystitis may be higher due to a higher risk of gallstone impaction in Hartmann’s pouch causing gallbladder outflow obstruction and acute cholecystitis. Prophylactic cholecystectomy may also be justified for diabetic patients with asymptomatic gallstones as acute cholecystitis may be more dangerous in these patients. Other situations where prophylactic cholecystectomy may be justified for asymptomatic gallstones include the very young, haemolytic disease, non-hepatic transplantation and porcelain gallbladder, where chronic infection associated with gallstones has resulted in calcification of the gallbladder wall (Figs 26.1 and 26.2). In all such cases, the clinical decision making should include appropriate specialist advice.

Incidentally detected gallbladder polyps

Polyps in the gallbladder are usually asymptomatic and are frequently detected by upper abdominal ultrasound carried out for other reasons. On ultrasound scanning, gallbladder polyps are differentiated from gallstones by their lack of mobility within the gallbladder (as they are attached to the gallbladder wall), and by the lack of acoustic shadowing that is a usual ultrasound scan feature of gallstones. Gallbladder polyps may be non-neoplastic or neoplastic. Non-neoplastic gallbladder polyps are made up of cholesterol and attached to the gallbladder epithelium so they do not move. Neoplastic (or adenomatous) gallbladder polyps arise from the gallbladder epithelium. Most gallbladder polyps are small (less than 1 cm) and most small gallbladder polyps are non-neoplastic. The risk that a polyp is an unsuspected gallbladder carcinoma is very low but increases with increasing polyp size. For this reason, polyps greater than 1 cm are generally removed by cholecystectomy. For polyps less than 1 cm the possibility of a small carcinoma is addressed by repeating the ultrasound in 3–6 months. If the lesion is stable the ultrasound is repeated at 12 months. A carcinoma would be expected to increase in size whereas small adenomatous polyps and cholesterol polyps are unlikely to change. Polyps larger than 1 cm or that enlarge should be regarded as suspicious, removed by cholecystectomy and submitted for histopathology.

Asymptomatic common bile duct dilatation

In normal patients younger than 60 years of age the upper limit of common bile duct size on ultrasound is 6 mm. This limit increases by 1 mm per decade after 60 years of age. The bile duct tends to be a little wider in women and also after cholecystectomy. Other causes of bile duct dilatation are listed in Box 26.3. The likelihood that incidentally detected common bile duct dilation is due to significant pathology and is revealing extrahepatic cholestasis is increased if the liver function tests, especially the serum bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels, are abnormal, so these are usually performed first. The likelihood of a malignant cause such as pancreatic head carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma is increased if the tumour marker CA-19-9 is elevated, so this too should be checked in the phase of non-invasive investigations, especially if the serum bilirubin and serum alkaline phosphatase level are raised.

Asymptomatic choledocholithiasis

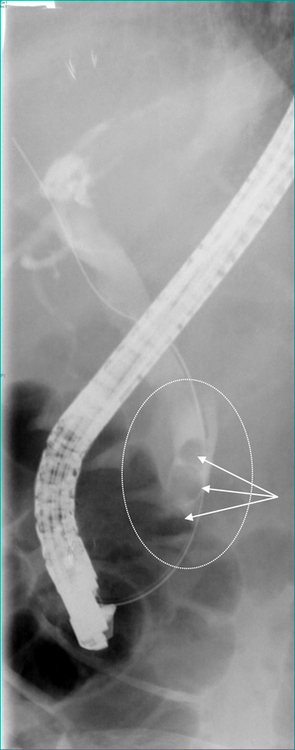

Where it is available, ERCP with endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic stone extraction is the most common treatment for common bile duct stones that do not pass spontaneously (Fig 26.3). If ERCP is not available the duct is usually cleared by laparoscopic or open surgery. If the gallbladder is still present it is usually removed at the same operation. Thus, if ERCP is not readily available or, in patients not needing urgent clearance of the bile duct, a two-stage treatment (ERCP and subsequent surgical removal of the gallbladder) can on occasion be condensed into a single phase treatment by omitting the ERCP and utilising a single surgical procedure to remove the gallbladder and clear the bile duct, usually laparoscopically.

Choledochal cysts

Choledochal cysts may occur anywhere in the biliary tree. They may be focal or diffuse, single or multiple. They are classified on the number of cysts present and on their position in the intra- or extrahepatic biliary tree (Table 26.1). Though not primarily caused by bile duct obstruction or by strictures, tumours or stones, all these problems may develop in association with them and may in turn lead to complications such as cholestasis (obstructive jaundice), infection in the biliary tree (cholangitis), impaired hepatic function (liver failure), hepatocellular loss and hepatic fibrosis (cirrhosis) and bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma).

Table 26.1 Todani classification of choledochal cysts

| Site of cyst | Classification | ERCP findings |

|---|---|---|

| Extrahepatic | I | Solitary fusiform cyst |

| II | Supraduodenal diverticulum | |

| III | Intraduodenal diverticulum (choledochocoele) | |

| IVB | Multiple extrahepatic cysts | |

| Extrahepatic and intrahepatic | IVA | Extra and intrahepatic cysts |

| Intrahepatic | V | Multiple intrahepatic cysts (Caroli’s disease) |

ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.

The discovery of intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct dilation consistent with choledochal cysts necessitates further investigation, initially by assessment of liver function and by MRCP or CT cholangiography. Masses associated with choledochal cysts anywhere in the biliary tree may be due to cholangiocarcinoma and should be assumed to be so until proven otherwise.

Pancreatic Incidentalomas

Unexpected imaging detected masses in the pancreas may be cystic or solid and may be derived from stromal, exocrine or endocrine elements of the pancreas. Lymph glands lying in or adjacent to the pancreas may also be responsible for incidentally detected asymptomatic pancreatic masses. As with incidentalomas elsewhere, the first step in non-invasive investigation of pancreatic incidentalomas is always to revisit the clinical history and examination. A past history of epigastric pain may correspond to a previous episode of pancreatitis. Epigastric pain associated with back pain may be consistent with pancreatic cancer, as would a history of nausea or weight loss. A palpable epigastric mass is possible and should be looked for but is unlikely unless a pancreatic lesion is very large. An enlarged supraclavicular lymph node, an umbilical nodule or a hepatic mass may betray previously unsuspected metastatic disease.