CHAPTER 24 Abdominal Hernias and Gastric Volvulus

DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

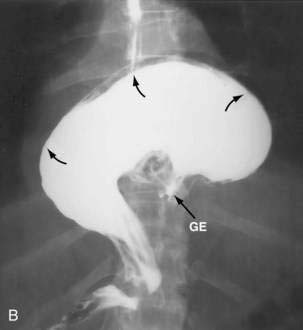

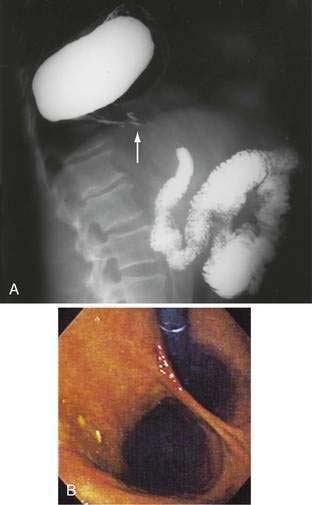

Paraesophageal hernias (type 2) occur when the stomach protrudes through the esophageal hiatus alongside the esophagus. The gastroesophageal junction typically remains in a normal position at the level of the diaphragm because there is preservation of the posterior phrenoesophageal ligament with normal anchoring of the gastroesophageal junction.1 The entire stomach can pass into the chest (Fig. 24-1A). Gastric volvulus (see later) may result. The omentum, colon, or spleen may also herniate. Patients with paraesophageal hernias may have a congenital defect in the diaphragmatic hiatus anterior to the esophagus. Most paraesophageal hernias contain a sliding hiatal component in addition to the paraesophageal component, and are thus mixed diaphragmatic hernias (type 3; see Fig. 24-1B).2 A barium study is often obtained to diagnose these defects. Very specific questioning of the radiologist with respect to two critical points will allow the clinician to make an accurate diagnosis:

Figure 24-1. A, Paraesophageal hernia. This barium radiograph shows a paraesophageal hernia complicated by an organoaxial volvulus of the stomach (see Fig. 24-6). The gastroesophageal junction remains in a relatively normal position below the diaphragm (arrow). The entire stomach has herniated into the chest and the greater curvature has rotated anteriorly and superiorly. B, Combined hernia in a different patient. A retroflexed endoscopic view of the proximal stomach shows the endoscope traversing a sliding hiatal hernia adjacent to a large paraesophageal hernia.

(A courtesy of Dr. Herbert J. Smith, Dallas, Tex.)

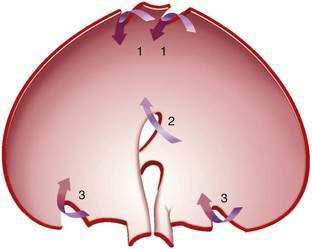

Congenital diaphragmatic hernias result from failure of fusion of the multiple developmental components of the diaphragm (Fig. 24-2). The diaphragm is derived from the septum transversum (separating the peritoneal and pericardial spaces), the mesentery of the esophagus, the pleuroperitoneal membranes, and muscle of the chest wall. Morgagni hernias form anteriorly at the sternocostal junctions of the diaphragm and Bochdalek hernias posterolaterally at the lumbocostal junctions of the diaphragm (Fig. 24-3).3 Bochdalek hernias manifest immediately after birth and are commonly associated with pulmonary hypoplasia.

Post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias are caused by blunt trauma (e.g., motor vehicle accidents) in about 80% of cases, and to penetrating trauma (e.g., stab wounds or gunshots) in the remainder. During blunt trauma, abrupt changes in intra-abdominal pressure may lead to large rents in the diaphragm. Penetrating injuries often cause only small lacerations. Blunt trauma is more likely than penetrating trauma to lead eventually to herniation of abdominal contents into the chest because the defect is usually larger. The right hemidiaphragm is somewhat protected by the liver during blunt trauma. Thus, 70% of diaphragmatic injuries from blunt trauma occur on the left side.4–6 Diaphragmatic injury may not result in immediate herniation but, with time, normal negative intrathoracic pressure may lead to gradual enlargement of a small diaphragmatic defect and protrusion of abdominal contents through the defect.7 Stomach, omentum, colon, small bowel, spleen, and even kidney may be found in a post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia.

Incidence and Prevalence

In the United States and Canada, a large proportion of adults undergoing upper gastrointestinal barium radiographs are found to have a small hiatal hernia. About 90% to 95% of hiatal hernias found by radiograph are sliding (type 1) hernias; the remainder are paraesophageal (type 2) or mixed (type 3).2 Most sliding hiatal hernias are small and of little clinical significance. Patients with symptomatic paraesophageal hernias are most often middle-aged to older adults.

Congenital hernias occur in about 1/2,000 to 10,000 births.8,9 Those hernias manifesting in neonates are most often Bochdalek hernias. With the routine use of prenatal ultrasound, congenital diaphragmatic hernias (CDHs) can be discovered in the prenatal period. The presence of intra-abdominal contents in the chest during fetal development results in significant hypoplasia of the lung. It is the degree of pulmonary dysfunction, not the presence of the hernia per se, that determines the child’s prognosis. Prenatal measures are then taken to prepare for the pulmonary hypoplasia that invariably accompanies a large CDH. Only a few Bochdalek hernias are first discovered in adulthood.10 Bochdalek hernias occur on the left side in about 80% of cases (see Fig. 24-3).11 Right-sided Bochdalek hernias usually contain liver in the right chest. Morgagni hernias make up about 2% to 3% of surgically treated diaphragmatic hernias.12,13 Although thought to be congenital, they usually manifest in adults and occur on the right side in 80% to 90% of cases. The incidence of post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernia is uncertain. Diaphragmatic injury occurs in about 5% of patients with multiple traumatic injuries.5,6

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Many patients with small simple sliding hiatal hernias are asymptomatic. The main clinical significance of the sliding hiatal hernia is its contribution to gastroesophageal reflux (see Chapter 43). In addition to heartburn and regurgitation, patients with large sliding hiatal hernias may complain of dysphagia or discomfort in the chest or upper abdomen. In a prospective, population-based study, the risk of iron deficiency anemia in adults was found to be increased by almost threefold.14 With chest radiography, a hiatal hernia may be noted as a soft tissue density or an air-fluid level in the retrocardiac area. Hiatal hernias are most often diagnosed on upper gastrointestinal barium studies. Computed tomography (CT) scanning can demonstrate the proximal stomach above the diaphragmatic hiatus. At endoscopy, the gastroesophageal junction is noted to be proximal to the impression of the diaphragm.

Cameron lesions or linear erosions may develop in patients with sliding hiatal hernias, particularly large hernias (see Chapters 19 and 52). These mucosal lesions are usually found on the lesser curve of the stomach at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus (Fig. 24-4). This is the location of the rigid anterior margin of the hiatus formed by the central tendon of the diaphragm. Mechanical trauma, ischemia, and peptic injury have been proposed as the cause of these lesions. The prevalence of Cameron lesions in patients with hiatal hernias who undergo endoscopy has been reported to be about 5%, with the highest prevalence in the largest hernias. Cameron lesions may cause acute or chronic upper gastrointestinal bleeding.15 The presence of Cameron lesion(s) and occult gastrointestinal bleeding may prompt repair of the hiatal defect to aid healing of this defect.

Patients with paraesophageal or mixed hiatal hernias are rarely completely asymptomatic if closely questioned. About half of patients with paraesophageal hernias have gastroesophageal reflux.2,16,17 Other symptoms include dysphagia, chest pain, vague postprandial discomfort, and shortness of breath, and a substantial number of patients will have chronic gastrointestinal blood loss.18–20 If the hernia is complicated by gastric volvulus, acute abdominal pain and retching will occur, often progressing rapidly to a surgical emergency (see later, “Gastric Volvulus”). A paraesophageal or mixed hiatal hernia may be seen on a chest radiograph as an abnormal soft tissue density (often with a gas bubble) in the mediastinum or left chest. Upper gastrointestinal radiography is the best diagnostic study (see Fig. 24-1A). CT scanning can demonstrate that part of the stomach is in the chest. Lack of filling the gastric lumen with contrast or gastric wall thickening with pneumatosis can increase suspicion for a volvulus and associated gastric necrosis. Paraesophageal hernias are usually obvious on upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (see Fig. 24-1B), but the paraesophageal component of a large mixed hernia may be missed. Endoscopy may be difficult if the hernia is associated with gastric volvulus.

The clinical presentation of congenital diaphragmatic hernias varies greatly, from death in the neonatal period to an asymptomatic serendipitous finding in adults. Newborns with Bochdalek hernia have respiratory distress, absent breath sounds on one side of the chest, and a scaphoid abdomen.11 Most of these neonates are diagnosed in utero with routine use of prenatal ultrasound. Serious chromosomal anomalies are found in 30% to 40% of cases; the most common of these are trisomy 13, 18, and 21. Pulmonary hypoplasia occurs on the side of the hernia, but some degree of hypoplasia may also occur in the contralateral lung. Pulmonary hypertension is common. The major causes of mortality in infants with Bochdalek hernias are respiratory failure and associated anomalies. Prenatal diagnosis may be made sonographically by visualizing stomach or loops of bowel in the chest. The diagnosis of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in the prenatal period will make the pregnancy high risk. Pediatric surgeons are available at delivery to initiate extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), because the neonate will commonly need complete cardiopulmonary bypass because of the lack of pulmonary function. The hernia will then be repaired using a large mesh prosthesis once the child has stabilized from a pulmonary standpoint.

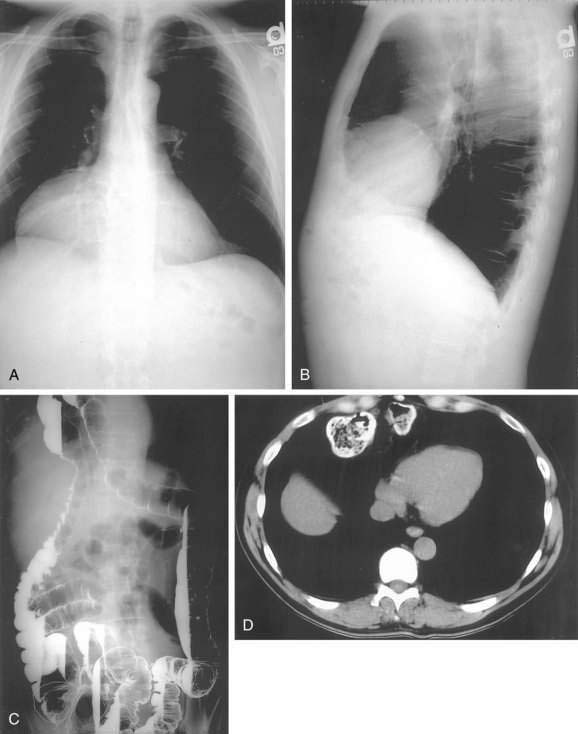

In older children and adults, a Bochdalek hernia may manifest as an asymptomatic chest mass. The differential diagnosis includes mediastinal or pulmonary cyst or tumor, pleural effusion, or empyema. Symptoms, when present, are caused by herniation of the stomach, omentum, colon, or spleen. About half of adult patients present with acute emergencies caused by incarceration. Gastric volvulus is common (see later). Other patients may have chronic intermittent symptoms, including chest discomfort, shortness of breath, dysphagia, nausea, vomiting, and/or constipation. The diagnosis may be suspected on a chest radiograph, particularly a lateral view. The key finding is a posterior chest mass because the defect of Bochdalek is posterior (see Fig. 24-3) as opposed to the Morgagni defect, which is anterior (Fig. 24-5). The diagnosis may be confirmed by barium upper gastrointestinal radiography or CT scanning.8,10,11

Morgagni hernias are most likely to manifest in adult life. They may contain omentum, stomach, colon, or liver. Bowel sounds may be heard in the chest if bowel has herniated through the defect. As with Bochdalek hernias, the diagnosis is often made by chest radiography, particularly the lateral view, because Morgagni hernias are anterior (see Fig. 24-5A and B). The contents of the hernia can be confirmed with barium radiography or CT scanning (see Fig. 24-5C and D). The differential diagnosis is similar to that of Bochdalek hernias. Many patients have no symptoms or nonspecific symptoms, such as chest discomfort, cough, dyspnea, or upper abdominal distress. Gastric, omental, or intestinal incarceration with obstruction and/or ischemia may cause acute symptoms.12,13

Post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias cause respiratory or abdominal symptoms. After serious trauma, rupture of the diaphragm is often masked by other injuries.4 Penetrating injuries between the fourth intercostal space and the umbilicus should raise the level of suspicion of a diaphragmatic injury. Respiratory or abdominal symptoms manifesting several days to weeks after injury should suggest the possibility of a missed diaphragmatic injury. The diaphragm must be closely inspected to detect injury at the time of exploratory laparotomy because these injuries can be easily missed. Careful examination of the chest radiograph or CT scan is important, but is diagnostic in only half of cases. The use of rapid helical CT, especially with sagittal reconstruction, has facilitated the diagnosis.5,6 In patients on ventilatory support after trauma, positive intrathoracic pressure may prevent herniation through a diaphragmatic tear. However, on attempted ventilator weaning, herniation may occur, causing respiratory compromise. Symptoms may also manifest long after injury. Delays of more than 10 years are not uncommon.7 In such cases, the patient may not connect the acute illness with remote trauma.

Treatment and Prognosis

Simple sliding hiatal hernias do not require treatment. Patients with symptomatic giant sliding hiatal hernias, paraesophageal, or mixed hernias should be offered surgery. When closely questioned, most patients with type 2 or 3 hernias will have symptoms.1 In the past, paraesophageal hernias were thought to be a surgical emergency. However, it is now clear that the risk of progression to gastric necrosis is lower than initially believed.17 However, many experts suggest that surgery should be offered to all patients with paraesophageal hernias because some complication will develop in about 30% of patients if left untreated.2,18–20 In general, a selective approach to patients with large paraesophageal hernias is warranted; those with any symptoms that may be attributable to the hernia should be offered surgical intervention.

The extent of the preoperative evaluation needed for paraesophageal hernia repair is controversial. Many surgeons recommend routine preoperative evaluation with esophageal manometry and ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring because of the high prevalence of associated gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal motility disorders. The object of the evaluation is to determine which patients should have a fundoplication and whether to perform a complete or partial wrap. However, complete manometry is frequently not possible in these patients, and anatomic distortions make it difficult to place the pH probe in the correct location, making esophageal pH monitoring unreliable.21–24 The main use of manometry is to ensure that the patient has an excellent primary peristaltic wave rather than to identify the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure. Patients with dysphagia should be studied to ensure that significantly abnormal motility is not present. Many surgeons routinely add a fundoplication to all repairs to prevent postoperative reflux esophagitis and to fix the stomach in the abdomen. However, in patients with motility disorders, the surgeon may elect to perform a loose posterior wrap or simply a gastrostomy or gastropexy to fix the stomach intra-abdominally. Addition of gastropexy may, in fact, reduce the recurrence rate after hernia repair.25

The principles of surgery for hiatal or paraesophageal hernias include three main elements: (1) reduction of the hernia from the mediastinum or chest with excision of the hernia sac; (2) reconstruction of the diaphragmatic hiatus with simple closure or use of prosthetic mesh; and (3) fixation of the stomach in the abdomen with a wrap, gastropexy, or gastrostomy tube. These elements can be accomplished laparoscopically or via open operation and may be approached through the abdomen or the chest. Most patients are approached laparoscopically with a shorter hospital stay and less postoperative pain26 and an equivalent risk of recurrence. Reduction of chronic paraesophageal hernias from the chest can be difficult and may be approached through a combined thoracoscopic and abdominal procedure. Injury to the lung can occur with vigorous traction; however, as the diaphragmatic defect is central, rather than peripheral, as in the traumatic defect, intense lung adhesions are usually not present. Resection of the hernia sac can result in violation of the left chest, requiring chest tube placement. Reconstruction of the diaphragm can be performed by placing nonabsorbable sutures anterior or posterior to the esophagus.22,23 The use of prosthetic mesh has resulted in fewer recurrences.27–31 Fixation of the stomach in the abdomen is usually achieved by using a wrap, which provides some bolstering effect at the hiatus to keep the stomach in the abdomen and can reduce postoperative gastroesophageal reflux. Additional use of gastropexy, with suturing of the stomach to the abdominal wall or tube placement, may result in fewer recurrences.25

Patients with sliding hiatal or paraesophageal hernias may have shortening of the esophagus. This makes it difficult to restore the gastroesophageal junction below the diaphragm without tension, a key factor in decreasing recurrence. In such cases, an extra length of neoesophagus can be constructed from the proximal stomach (Colles-Nissen procedure).32 In this situation, a stapler is fired parallel to the axis of the esophagus along a bougie that is passed into the stomach, creating a lengthened esophagus. Alternatively, transmediastinal dissection of the esophagus for more than 5 cm into the chest will usually result in adequate intra-abdominal length of esophagus, without the need for additional stapling.33 Paraesophageal and mixed hernias can be repaired through the chest or abdomen, with open or laparoscopic techniques.2,18–20,26,34,35 Compared with open repair, laparoscopic repair is associated with less blood loss, fewer overall complications, and shorter hospital stay, and return to normal activities is faster. Long-term results are probably equal with either approach. Potential surgical complications include esophageal and gastric perforation, pneumothorax, and liver laceration; potential long-term complications may include dysphagia if the wrap is too tight or gastroesophageal reflux if the fundoplication breaks down or migrates into the chest. When examined closely, recurrence after paraesophageal hernia repair is 25% to 30%.36,37 However, the clinical impact of a recurrence may be minimal, because most of these patients remain symptom-free. Like other gastric ulcers, Cameron ulcers or erosions are initially treated with antisecretory medication (see Chapter 53). However, Cameron lesions may persist or recur despite antisecretory medication in about one third of patients, in which case surgical repair of the associated hernia may be required.15

The first priority of treatment for infants with Bochdalek hernias is adequate ventilatory support. Newer techniques of ventilation such as high-frequency oscillation and ECMO are very helpful in some cases. Ventilatory support allows infants to be stabilized before diaphragmatic repair. From 39% to 77% of infants survive the neonatal period after repair, but a significant number have long-term neurologic and musculoskeletal problems, and as many as 50% experience gastroesophageal reflux.11

Laparoscopic repair of Bochdalek hernias has been reported.10 Morgagni hernias have been repaired through the chest or abdomen, using open, thoracoscopic, and/or laparoscopic techniques.12,13,38–40

Acute diaphragmatic ruptures may be approached from the abdomen during exploratory laparotomy or through the chest. Diagnostic laparoscopy has been used in patients who are thought to have a high risk of diaphragmatic injury (e.g., after a stab wound to the lower chest). Chronic post-traumatic diaphragmatic hernias may be associated with extensive adhesions and lack of a peritoneal hernia sac. In such cases, repair is best done through the chest or by a combined thoracoscopic-abdominal approach, although laparoscopic repair has been reported.5,41

GASTRIC VOLVULUS

Cause and Pathogenesis

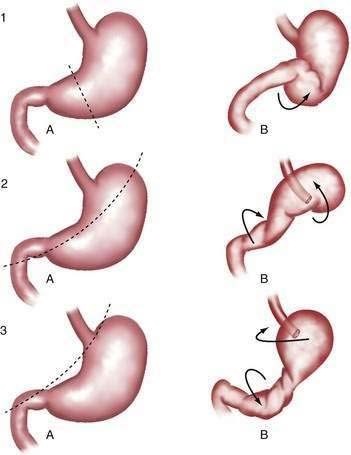

Gastric volvulus may be mesenteroaxial (40%) or organoaxial (60%; Fig. 24-6). In organoaxial volvulus, the stomach twists along its long axis. This axis usually passes through the gastroesophageal and gastropyloric junctions. The antrum rotates anteriorly and superiorly and the fundus posteriorly and inferiorly, twisting the greater curvature at some point along its length (see Fig. 24-6, 3A and 3B). Less commonly, the long axis passes through the body of the stomach itself, in which case the greater curvature of the antrum and fundus rotate anteriorly and superiorly (Fig. 24-7; see Fig. 24-6, 2A and 2B). This type of volvulus is commonly associated with a diaphragmatic hernia. Organoaxial volvulus is usually an acute event. Vascular compromise and gastric infarction may occur.

In mesenteroaxial volvulus, the stomach folds on its short axis, running across from the lesser curvature to the greater curvature (see Fig. 24-6, 1A and 1B), with the antrum twisting anteriorly and superiorly. In rare cases, the antrum and pylorus rotate posteriorly. Mesenteroaxial volvulus is more likely than organoaxial volvulus to be incomplete and intermittent, and to manifest with chronic symptoms. Mixed mesenteroaxial and organoaxial volvulus has also been reported.42

Incidence and Prevalence

The incidence and prevalence of gastric volvulus are unknown. It is difficult to estimate how many cases are intermittent and undiagnosed. About 15% to 20% of cases occur in children younger than 1 year of age, most often in association with a congenital diaphragmatic defect. The peak incidence in adults is in the fifth decade. Men and women are equally affected.43–45

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Acute gastric volvulus causes sudden severe pain in the upper abdomen or lower chest. Persistent unproductive retching is common. In cases of complete volvulus, it is impossible to pass a nasogastric tube into the stomach. Hematemesis is rare, but may occur because of an esophageal tear or gastric mucosal ischemia.45 The combination of pain, unproductive retching, and inability to pass a nasogastric tube is called Borchardt’s triad. Symptoms of acute gastric volvulus may be mistaken for a myocardial infarction or an abdominal catastrophe such as biliary obstruction or acute pancreatitis.43,44 If the volvulus is associated with a diaphragmatic hernia, physical examination may reveal evidence of the stomach in the left chest. Plain chest or abdominal films will show a large gas-filled viscus in the chest. A barium upper gastrointestinal radiograph will confirm the diagnosis. Upper endoscopy may show twisting of the gastric folds (Fig. 24-8). Endoscopy is not prudent if gastric ischemia is suspected.

Chronic gastric volvulus is associated with mild and nonspecific symptoms such as dysphagia, epigastric discomfort or fullness, bloating, and heartburn, particularly after meals. Symptoms may be present for months to years.43,45 It is likely that a substantial number of cases are unrecognized. The diagnosis should be suspected in the proper clinical setting if an upper gastrointestinal radiograph or CT scan shows a large diaphragmatic hernia, even if the stomach is not twisted at the time of the radiograph.46

Treatment and Prognosis

Acute gastric volvulus is an emergency. Nasogastric decompression should be performed if possible. If signs of gastric infarction are not present, acute endoscopic detorsion may be considered. Using fluoroscopy, the endoscope is advanced to form an alpha loop in the proximal stomach. The tip is passed through the area of torsion into the antrum, or duodenum if possible, avoiding excess pressure. Torque may then reduce the gastric volvulus.47 The risk of gastric rupture should be weighed against the possible benefit of temporary detorsion. Surgery for gastric volvulus may be done by open or laparoscopic techniques. In recent years, there has been a trend toward laparoscopic repair.44,48 After the torsion is reduced, the stomach is fixed by gastropexy or tube gastrostomy. Associated diaphragmatic hernia must be repaired.45,49 Combined endoscopic and laparoscopic repair or simple endoscopic gastropexy by placement of a percutaneous gastrostomy tube has been reported.47–52 Chronic gastric volvulus is treated in the same manner as acute volvulus. The surgeon may elect to treat an associated paraesophageal component in the usual manner, with repair of the diaphragm and wrap, if the patient is clinically stable. Acute gastric volvulus has carried a high mortality in the past. However, in one reported series, there were no major complications or deaths in 36 patients with gastric volvulus, including 29 who presented acutely.

INGUINAL AND FEMORAL HERNIAS

Cause and Pathogenesis

The abdominal wall is protected from hernia formation by several mechanisms. In the lateral abdominal wall, there are layers of muscles that together with intervening fascia, provide support. These muscles travel at oblique angles to each other and therefore handle forces in various planes, affording greater support than if they were parallel to each other. In the central abdomen, the bulky rectus abdominis muscles provide a barrier to herniation. Abdominal wall hernias occur in areas in which these muscles and fascial layers are attenuated, and they can be congenital or acquired. In the groin, there is an area that is prone to herniation bound by the rectus abdominis muscle medially, the inguinal ligament laterally, and the pubic ramus inferiorly. The aponeurosis of the transverses abdominis muscle provides the deep layer for this area. In this area, the external and internal oblique muscles thin to a fascial aponeurosis only, so that there is no muscular support of the transverse abdominal fascia and the peritoneum. Upright posture causes intra-abdominal pressure to be constantly directed to this area. During transient increases in abdominal pressure, such as occur with coughing, straining, or heavy lifting, reflex abdominal muscle wall contraction narrows the myopectineal orifice and tenses the overlying fascia (shutter mechanism).53 For this reason, hernias are not more common in laborers than in sedentary persons. However, conditions that chronically increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., obesity, pregnancy, and ascites) are associated with an increased risk of hernia. Chronic muscle weakness and deterioration of connective tissue (caused by aging, systemic disease, malnutrition, or smoking) promote hernia formation.

During embryologic development, the spermatic cord and testis in men (the round ligament in women) migrate from the retroperitoneum through the anterior abdominal wall to the inguinal canal, along with a projection of peritoneum (processus vaginalis). The defect in the abdominal wall (internal inguinal ring) associated with this process represents an area of potential weakness through which an indirect inguinal hernia may form (Fig. 24-9). The processus vaginalis may persist in up to 20% of adults, further predisposing to hernia formation. Direct inguinal hernias do not pass through the internal ring but rather protrude through defects in an area called Hesselbach’s triangle, bounded by the rectus abdominis muscle, the inferior epigastric artery, and the inguinal ligament (see Fig. 24-9). Therefore, indirect inguinal hernias travel with the spermatic cord (or round ligament) and are found lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels; direct hernias are found in the floor of the inguinal canal—an area supported only by the weak transversalis fascia—and are medial to the epigastric vessels.

Femoral hernias pass through the opening associated with the femoral artery and vein. They manifest inferior to the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral artery (see Fig. 24-9).53 Clinical examination cannot easily differentiate indirect from direct inguinal hernias.54 The importance of distinguishing these two entities preoperatively is not critical because the operative approach and repair is identical. However, it is important to diagnose femoral hernias accurately because they can be mistaken for lymph nodes in the groin. Misdiagnosis of an incarcerated loop of bowel in a femoral defect as a lymph node can lead to fine-needle aspiration of the mass and bowel injury.

Incidence and Prevalence

The overall incidence of groin hernias in American men is 3% to 4% if determined through interview, and about 5% if determined by physical examination. The incidence increases with age, from 1% in men younger than 45 years to 3% to 5% in those older than 45 years. About 750,000 groin hernia repairs are done annually in the United States. Of these, 80% to 90% are done in men. Indirect inguinal hernias account for about 65% to 70% of groin hernias in men and women. In men, direct inguinal hernias account for about 30% and femoral hernias for about 1% to 2%, whereas in women the opposite is true. Groin hernias are somewhat more common on the right than on the left side.55

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Many groin hernias are asymptomatic. The most common symptom is a mass in the inguinal or femoral area that enlarges when the patient stands or strains. An incarcerated hernia may produce constant discomfort. Strangulation causes increasing pain. Symptoms of bowel obstruction or ischemia may occur. In a Richter-type hernia, pain from bowel strangulation may occur without symptoms of obstruction, as only one wall of the intestine is involved in the hernia. The patient should be questioned about risk factors for hernia formation (e.g., chronic cough, constipation, and symptoms of prostate disease). These factors, if not corrected prior to herniorrhaphy, can lead to recurrence.56–58

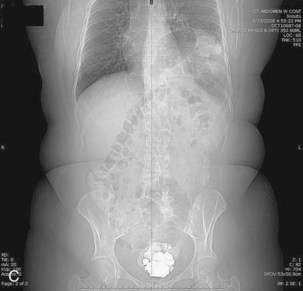

On physical examination, inguinal hernias present as a soft mass in the groin. The mass may be larger on standing or straining. It may be slightly tender. It may be possible to palpate the fascial defect associated with the hernia. The patient should be examined upright, the examiner’s finger should be inserted into the femoral canal, and a prolonged Valsalva maneuver should be initiated. It is normal to feel a small impulse against the examining finger with coughing; however, when a hernia is present, a prolonged Valsalva maneuver will result in the protrusion of the sac against the examiner’s finger. Direct and indirect hernias may be difficult to distinguish. Groin hernias may also be noted on a plain abdominal radiograph (Fig. 24-10), barium radiograph, sonogram, or CT scan.

Figure 24-10. Plain radiograph of a 28-year-old man with a giant incarcerated inguinal hernia.

(Courtesy of Dr. Michael J. Smerud, Dallas, Tex.)

Femoral hernias are more difficult to diagnose than other groin hernias. Two thirds of femoral hernias manifest as surgical emergencies. The correct diagnosis is often not made before surgery. The neck of femoral hernias is usually small. Even a small femoral hernia that is difficult to palpate may cause obstruction or strangulation. Richter’s hernias are most common in the femoral area, further complicating the diagnosis. Femoral hernias are most common in women, in whom clinicians may have a lower level of suspicion for hernia than in men. Femoral hernias also occur in children.59 Delay in diagnosis, strangulation, and need for emergency surgery are common.60–62 Any mass below the inguinal ligament and medial to the femoral artery should raise the suspicion of femoral hernia. Femoral hernias are commonly mistaken for femoral adenopathy or groin abscess. Obviously, bedside drainage of an incarcerated femoral hernia must be avoided and therefore liberal use of sonography or CT scanning is useful for distinguishing a hernia from adenopathy, abscess, or other mass.63 The radiologist should perform these examinations with and without a prolonged Valsalva maneuver to demonstrate even small defects.

Treatment and Prognosis

Many surgeons recommend repair of direct and indirect inguinal hernias, even if asymptomatic, but this is controversial. A study by the American College of Surgeons has shown that males with minimally symptomatic groin hernias can be safely watched.64,65 This study randomized 720 male patients to elective hernia repair or watchful waiting. Only 2 of the 364 patients in the watchful waiting arm study developed complications related to their hernia in 4.5 years. This suggests that minimally symptomatic patients can be watched safely and have their hernia repaired when symptoms increase. Femoral hernias must be repaired promptly because the risk of strangulation is very high.60–62 Groin hernias can be repaired using various techniques. Historically, tissue repairs have been performed. However, several studies have shown a decreased recurrence rate with the use of mesh resulting in tension-free repairs.66–70 These can be performed by open surgery or laparoscopically.

The traditional tissue-based repairs were performed exclusively until the 1990s. There are two key components to successful hernia repair: (1) high ligation of the hernia sac, which treats the direct defect; and (2) repair of the floor of the canal, which treats the indirect defect. Even if there is no direct component, a repair of the floor is routinely undertaken. These repairs involve approach to the inguinal canal through a small incision parallel to the inguinal ligament and centered over the internal inguinal ring. Dissection is continued through the external oblique muscle, exposing the internal inguinal ring. The cord structures are then isolated and explored thoroughly to identify an indirect hernia sac. This is ligated and transected. The floor of Hesselbach’s triangle is then reinforced and strengthened by apposing the lateral border of the rectus abdominis aponeurosis to the inguinal ligament (Bassini or Shouldice repair) or to Cooper’s ligament (McVay repair).70–72 Tissue repairs inherently are not tension-free and pose a greater risk of recurrence than tension-free mesh repairs (see later). However, in cases in which there is probable contamination (e.g., in a strangulated hernia), it is important to perform a primary tissue repair and not a mesh repair because there is a high risk of mesh infection.

Open mesh repairs are most commonly performed as described by Lichtenstein.66–68 These can be performed under local, regional, or general anesthetic.73,74 The two major components of successful repair remain, with high ligation of the sac; however, the floor is repaired using synthetic mesh to bridge the gap between the conjoint tendon (the edge of the rectus aponeurosis) and inguinal ligament. The mesh can be sutured or stapled in place. Mesh plug repairs have also been developed.75–77 In these cases, minimal dissection is undertaken and the mesh plug, which looks like a badminton shuttlecock, is laid into the defect and tacked in place with a few sutures. The mesh causes fibroblast ingrowth and scarring that leads to strengthening of the floor of the inguinal canal. Mesh repairs have the advantage of being somewhat simpler to perform than tissue repairs and have less tension, less acute pain, and a decreased rate of recurrence.58,66,76,78 Most inguinal hernia repairs in the United States are currently done with mesh.55 Bilateral, very large, or complex abdominal hernias can be repaired with a large mesh that reinforces the entire ventral abdominal wall. This is called giant prosthetic reinforcement of the visceral sac (GPRVS), or the Stoppa procedure.79–81

Repair of groin hernias may be done with open or laparoscopic techniques.82–86 Several series have compared open hernia repair with laparoscopic repair. The largest and most recent study was performed by the Veterans Cooperative group.86 Almost 1700 patients were followed for two years after being randomized to open versus laparoscopic repair of inguinal hernias. Patients who had their hernias repaired laparoscopically had less pain initially and returned to work one day sooner than those who had open repair. However, the recurrence rate was higher in the laparoscopic group (10% vs. 4% in the open group) and complication rates were higher and more serious in the laparoscopic group compared with the open repair group. In another multicenter, prospective, randomized study performed in the United Kingdom, open repair, primarily using mesh, was compared with laparoscopic repair.82 The recurrence rate after laparoscopic repair was 7% compared with 0% after open repair. As in the U.S. study, patients returned to normal activities more quickly after laparoscopic repair than after open repair. The overall complication rate was lower after laparoscopic repair, but three serious complications occurred after laparoscopy, and none after open repair.84

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree