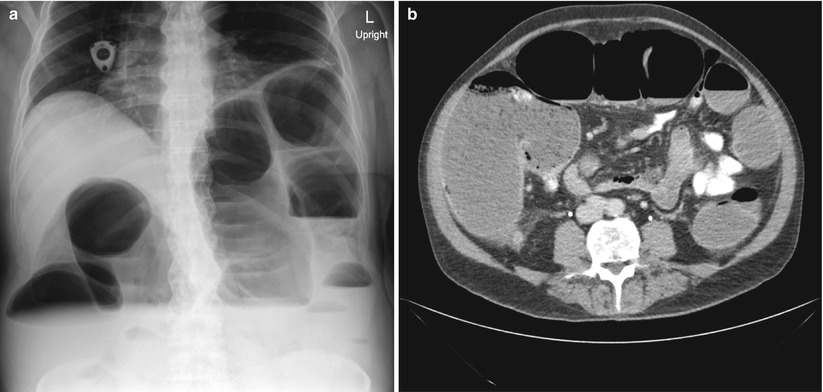

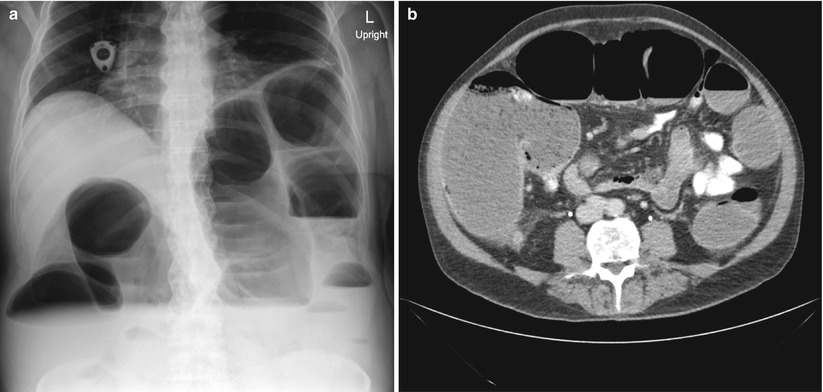

Fig. 6.1

CT scan images of two patients presenting with metastatic involvement of the liver. Image (a) represents a 47-year-old woman with rectal cancer and multiple, bilobar liver lesions. Image (b) represents a 54-year-old man with rectosigmoid cancer and a single site of metastatic disease in the liver. Both patients have been treated with a multidisciplinary approach and are currently free of disease

Multidisciplinary Approach

Key Concept: A multidisciplinary tumor board to review the specifics of each individual patient’s case provides a great opportunity to determine the ideal treatment plan and optimize outcomes.

A multidisciplinary approach to treatments of all types of cancer has long been advocated [2]. Given that many different modalities may be utilized in the treatment of Stage 4 colorectal cancer, a multidisciplinary approach is strongly recommended. The various disciplines can include surgery (including colorectal surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, thoracic surgery), medical oncology, radiation oncology, palliative care, radiology, and pathology. Through a thorough discussion of the patient’s overall condition and symptoms, the goals of care and potential curative versus palliative intent of treatment can be made. Many centers employ a tumor board conference where an individual case can be presented to representatives from each of the above specialties. A review of the patient’s history, relevant radiologic studies, pathology, and general medical condition can be made followed by discussion and input from all members of the team. This will allow for understanding of the condition of the patient, any prior treatments, as well as an explanation of goals of care. An honest discussion of the realistic expectations and prognosis of the patient can occur as well. Finally, the team can formulate a plan to include inclusion/exclusion of each therapeutic modality as well as discuss and plan for timing of each of the included treatments. This up-front communication will assure that all members of a patient’s treatment team are “on the same page.” An additional by-product of this is that the patient may further benefit from this communication by frequently precluding the need for multiple initial consults, thereby saving the patient time and energy.

Often, the questions raised at the multidisciplinary meeting revolve around timing of chemotherapy and/or radiation and the role of surgical resection. Occasionally, the oncologists and surgeons disagree as to the expectations of therapy, appropriate timing of the various therapeutic options, or when care is futile. It is not always clear which opinion is most appropriate for the patient, especially with very complex cases that cannot easily be compared to a specific trial or literature search for guidance. In cases where there are strongly held opinions that are divergent, it should be recommended to the patient to obtain a second opinion, most often from both medical oncology as well as another experienced surgeon.

Evolution of Care

Key Concept: Improvements in chemotherapeutics have allowed longer survival and an evolving role for resection following response to therapy.

In the past, many patients presenting with Stage 4 disease were started on chemotherapy (5-FU and leucovorin), and there was often felt to be a limited role for any operation. As chemotherapeutics have evolved over the last two decades (with the addition of oxaliplatin, irinotecan, cetuximab, bevacizumab, and others), patients are living longer (median survival up to 24 months or more) than ever before [3, 4], and an ever-increasing number of patients have a realistic chance of cure. As we continue to better understand the biology of colorectal cancers and the role for various adjuvant therapies, outcomes will continue to improve. A significant number of patients with initially surgically incurable disease burden are currently being treated aggressively with what has become neoadjuvant chemotherapy to the point that surgical options for cure are once again entertained. An example of this would be a patient presenting with extensive liver metastases to the point that curative resection is not feasible. After several rounds of chemotherapy, the tumor burden in the liver is reduced to the point that curative intent treatment is possible.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently approved two new chemotherapy agents for the treatment of metastatic disease. Aflibercept (commercial name Zaltrap™, also known as VEGF Trap) is a fusion protein which binds all forms of vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), as well as VEGF-B, and placental growth factor (PIGF). The VELOUR study was a multinational, randomized, double-blind trial comparing FOLFIRI in combination with either Zaltrap™ or placebo. The study randomized 1,226 patients who previously had been treated with an oxaliplatin-based regimen. The addition of Zaltrap™ to the FOLFIRI regimen significantly improved both overall survival (13.5 vs. 12.1 months) and progression-free survival (6.9 vs. 4.7 months) [5].

The FDA also recently approved regorafenib (commercial name Stivarga™), an oral multi-kinase inhibitor which targets angiogenic, stromal, and oncogenic receptor tyrosine kinases. The CORRECT study enrolled 760 individuals whose disease had progressed during or within 3 months following the last administration of approved standard therapies. Median overall survival for regorafenib was 6.4 months, compared with 5.0 months for those who received placebo [6]. While modest improvements in survival with these additional agents may not significantly change practice patterns, they represent other options for patients with previously recalcitrant disease.

The past two decades have not only seen an improvement in available chemotherapeutic agents, but we have also seen an improvement in the understanding of the role of liver resection for metastatic lesions as well as the enhanced utilization of ablative techniques (e.g., radiofrequency ablation). Indications for operation have broadened, while contraindications have loosened as the operations have become safer and more common (see below—Liver Metastases).

Indications for Operation

Key Concept: Clear communication with the patient and their family is critical to discuss the goals and realistic expectations of an operation in the setting of metastatic disease.

There are two general goals of an operation: curative and palliative. More to the point, when discussing the indication for operation in patients with colorectal cancer, the goal is generally either to attempt a cure (curative) or to relieve a specific symptom (palliative). The specific indication for a patient set to undergo palliative operation will depend upon the symptom/complaint to be alleviated, such as to relieve an obstruction. It is important that during preoperative discussions and evaluation, the surgeon clearly identifies the goal of an operation with the patient and family members. A realistic discussion of prognosis is important in order for the patient to understand any proposed procedure and to have realistic expectations of the operation as well as the postoperative course.

Of the roughly 20 % of patients that present with Stage 4 disease, there is a substantial subset that has a realistic chance of being treated and cured, for example, a patient with colon cancer and unilobar liver metastases. There are multiple options for treatment of this patient in terms of order of therapy. In general, the patient will benefit from chemotherapy and surgical resection of both the primary as well as the liver for cure. Again, a strong recommendation for multidisciplinary planning is made. Traditionally, these patients underwent colon resection followed by liver resection (or occasionally synchronously) followed by systemic chemotherapy. Recently, many experts have recommended taking a “liver first” approach to these patients and perhaps proceed with systemic chemotherapy to establish an effective regimen, followed by liver resection [7]. The colon resection may also occur at the same operation, or, alternatively, they may be performed in a staged setting. We generally base that decision upon the condition of the patient, the extent and difficulty of the liver and colonic resections, and how well/easily the liver resection goes. For staged operations, some patients will benefit from further systemic chemotherapy between the procedures [8]. Alternatively, the patient could undergo the second resection prior to resumption of systemic chemotherapy. Our bias is to base recommendations for treatment on the patient’s symptoms and response to therapy. Colonic lesions that virtually “melt away” are left to further rounds of chemotherapy (Fig. 6.2), whereas significant bleeding or nearly obstructive lesions typically warrant consideration for resection followed by completion chemotherapy.

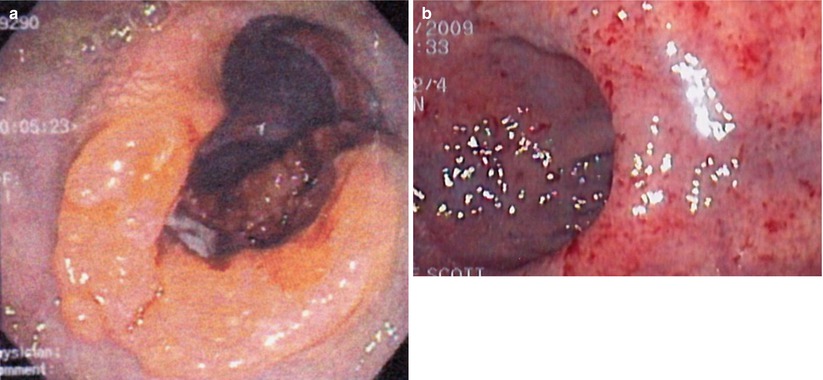

Fig. 6.2

Endoscopic view pre- (a) and post- (b) chemoradiation therapy demonstrating complete regression of the tumor (Courtesy of Scott R. Steele MD)

Unfortunately, some patients will present with Stage 4 disease for which cure is not realistic. Determining which symptoms can be surgically palliated is a very difficult process. A patient may have vague symptoms and be found to have metastatic disease, but determining cause and effect for a specific symptom, and thereby determining the possibility of surgical palliation, can be challenging. Bowel obstruction may be a more intuitive predicament as CT scanning can often show the site of obstruction, in the case of malignant obstruction, a mass at the transition point (Fig. 6.3). The question becomes what to do about the obstruction. Options would include surgical resection, an intraluminal colonic stent, chemotherapy, or hospice, with or without placement of a gastrostomy tube to vent the GI tract. Each of these choices depends heavily on the extent of the disease and the condition and wishes of the patient. Obviously a relatively young patient with extensive disease but otherwise good reserve is often treated very differently from an octogenarian with CHF and chronic renal failure that may have a small amount of bleeding and isolated otherwise potentially resectable metastases. In general, a malignant bowel obstruction is a very serious and ominous occurrence. Historically, surgical procedures for these patients have been fraught with complications and an in-hospital mortality of 21–28 % [9, 10].

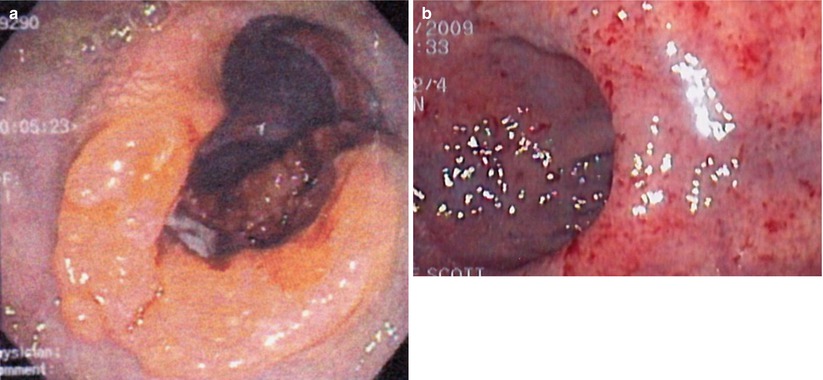

Fig. 6.3

Imaging of a malignant colon obstruction. Image (a) is plain film of distal colon obstruction, while Image (b) represents the corresponding CT scan image

In the case of suspected malignant bowel obstruction, each patient’s ability to undergo a major resection must be independently evaluated. Further, it is useful to determine what, if any, therapeutic options remain for the postoperative period (e.g., chemotherapy or radiation therapy). For patients with large bowel obstruction, we prefer endoscopic stenting when feasible and possible, at least initially. For patients with malignant small bowel obstruction, we generally will attempt one surgical exploration (laparoscopic when possible) for decompression via resection, internal bypass, or diversion. For a patient who is not suitable for exploration, or who is highly suspected to be inoperable based on imaging or prior attempts at relieving obstructions, a decompressive “venting” gastrostomy tube (percutaneous, endoscopic, or surgical) is often beneficial.

Should I Biopsy the Metastasis?

Key Concept: Unless otherwise directed by a multidisciplinary panel to guide therapy, metastatic disease in the setting of a known CRC does not require biopsy.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend that every patient with a diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer should undergo, among other things, a CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to evaluate for evidence of metastatic disease [11]. When abnormalities are found on these studies suggestive of metastases, a decision must be made regarding whether or not a biopsy of a metastatic site needs to be performed. CT findings can be quite suggestive of metastatic disease, and in the patient with a diagnosis of colorectal cancer, these findings alone are often adequate for initiation of treatment. In some cases, the addition of positron emission testing (PET) may further substantiate the need for systemic treatment, though the routine use of PET scan for every patient with a new diagnosis of colon or rectal cancer is not recommended by the NCCN [11]. In cases where there is some question about the diagnosis and the course of action would be altered if metastatic disease were confirmed, biopsy should be considered. We would generally recommend image-guided percutaneous needle biopsy where appropriate. However, for a patient with a known colorectal malignancy and CT findings strongly suggestive of malignant disease (and especially if the lesions are also PET-avid), routine biopsy is not necessary and may be harmful in terms of complications (e.g., bleeding) or tumor seeding.

What Should I Do with the Primary Lesion in the Patient with Extensive Disease?

Key Concept: While some evidence suggests improvement in outcomes with resection of the primary site, this has not been substantiated. Focus on the response to treatment and degree of symptoms.

Considering the primary tumor in the setting of metastatic disease, there has not been a clear consensus as to what, if anything, should be done. A recent review has suggested that there is a survival advantage to resection of the primary tumor [12]. They did note, however, that selection bias could in part be used to explain the advantage and, therefore, recommended further, prospective, studies. A subsequent Cochrane Review concluded that resection of the primary tumor is not associated with a survival benefit nor does it consistently result in a decrease in the tumor-related complications [13]. They felt that given the lack of strong evidence to recommend either for or against resection of the primary tumor, further clinical trials are warranted. In our practice (excepting for near obstruction), we will initiate chemotherapy and evaluate for the response to therapy. If the patient has a favorable or nearly complete clinical response (especially if the metastatic sites respond), we will reevaluate for resectability (Fig. 6.4). If imaging demonstrates resectable disease in a good surgical candidate, we will proceed with attempted resection of both sites. We have also come across the occasional case where there is a complete clinical response without any disease activity on PET (i.e., regression of all lesions) and have resected the primary site (Fig. 6.5). Ensuring the lesion is marked prior to chemotherapy (i.e., India ink tattoo, clip) has proved to be beneficial in this situation. Finally, for patients who continue to have progression, we must monitor for evidence of impending obstruction and be prepared to act accordingly.

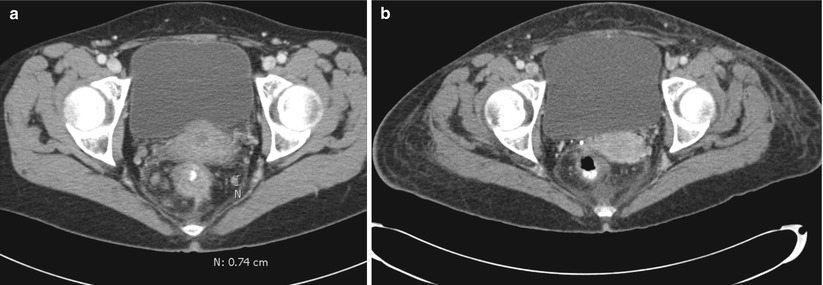

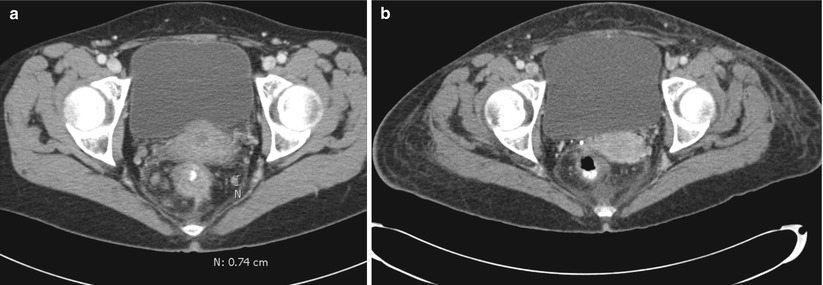

Fig. 6.4

CT Images pre- (a) and post- (b) chemoradiation therapy demonstrating tumor and lymph node regression

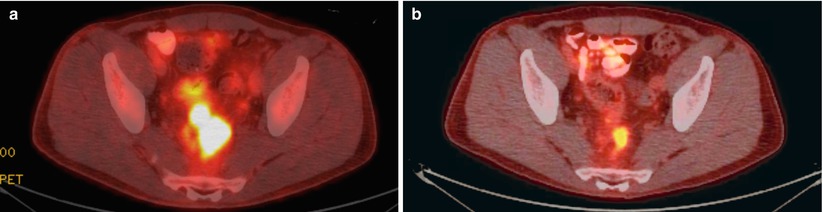

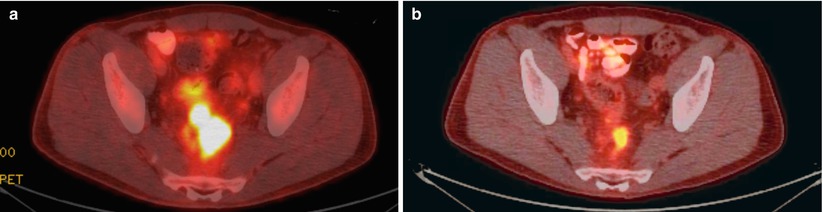

Fig. 6.5

Pre- (a) and post- (b) chemoradiation PET-CT images demonstrating absence of PET-positive activity on follow-up imaging

What Treatment Modality Should Come First?

Key Concept: The extent of the disease, primary symptoms, and ability of the patient to tolerate various options should be discussed among the multidisciplinary census to determine a unified treatment plan.

Decisions about the order of various treatments (chemotherapy, operation, stenting, radiation therapy in cases of rectal cancer) will depend upon the sites and extent of metastatic disease as well as symptoms—especially obstruction or impending obstruction of the primary lesion. Again, multidisciplinary discussions are highly recommended. For patients without evidence of obstruction, and isolated liver or lung metastases, up-front chemotherapy would generally be started, with operation reserved for the metastases and primary lesion after several rounds of chemotherapy, assuming that the lesions are responding. Subsequently, the surgical resection(s) can be undertaken, either in one operation or in staged procedures. The decision is much more difficult for patients with multisite metastatic disease. In the past, these patients were generally felt to be incurable, with the possible exception of an isolated pulmonary metastasis in concert with limited liver metastases. Currently, multisite metastases, including select patients with peritoneal spread, can be considered for aggressive curative intent treatment, but generally only if they show response to up-front chemotherapy.

For surgeons, it is important to take into consideration the specific chemotherapeutic agents the oncologists are planning to use. This is especially important with the increasing use of bevacizumab, as it has been linked to bowel perforations. There has therefore been some concern about treating metastatic disease with systemic chemotherapy and bevacizumab, while the primary tumor remains within the colon. However, McCahill and colleagues demonstrated that the use of mFOLFOX6 plus bevacizumab did not result in an increased rate of complications associated to the primary tumor [14]. When an operation is planned for a patient on bevacizumab, it is recommended to wait 6 weeks following the last dose of bevacizumab prior to operating if possible, in order to decrease surgical complications that may be attributed to the antiangiogenic effects of bevacizumab [15]. For all other chemotherapeutic agents, we typically delay any operation at least 4 weeks (6–8 weeks for bevacizumab) when feasible, but one must weigh the risks of operating with chemotherapeutics circulating versus continued symptoms or progression during the delay.

The Obstructed Patient: What Now?

Key Concept: Several methods exist to deal with an impending obstruction and are at least in part predicated on the symptoms and location of the lesion.

For patients with a colon or rectal obstruction/near obstruction, the first step of treatment is generally to relieve the obstruction. In broad terms this can be performed in three fashions: resection of the primary lesion, diversion via a proximal stoma, or utilizing an intraluminal stent. Most patients, when faced with these options, would choose to avoid a stoma and would therefore prefer an attempt at intraluminal stenting. Assuming that the lesion is not too low within the rectum and that the obstruction can be technically stented, there is a high technical success rate for placement of a stent [16–18]. The most recent series show both technical success and clinical success over 90 % of the time (Fig. 6.6). There is relatively low incidence of related morbidity, with migration, and tumor ingrowth being the most common (Fig. 6.7). Fortunately, perforation is uncommon although Manes et al. did note that the rate of perforation was considerably higher in patients receiving bevacizumab [17].

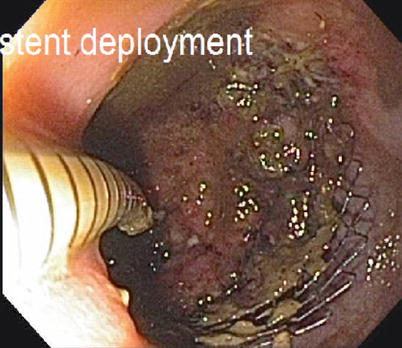

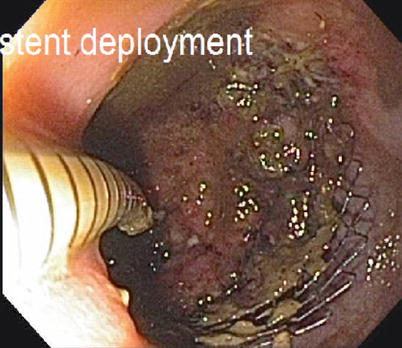

Fig. 6.6

Endoscopic placement of colonic stent

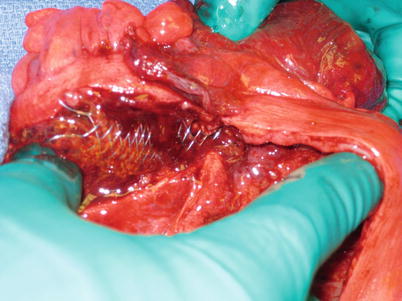

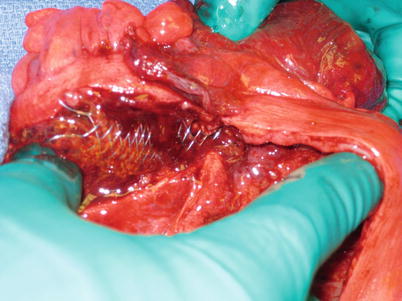

Fig. 6.7

Colonic stent perforation

For distal rectal lesions, there may not be enough space for placement of a stent. The distal end of the stent needs to be above the pelvic floor (levator muscles) to avoid patient discomfort from the stent (Fig. 6.8). When there is no sufficient room for placement of a stent, diversion (proximal stoma) or primary resection may be needed, depending on the degree of obstruction. Occasionally, laser recanalization can be effective in avoiding need for a stoma. Given that most such patients are candidates for pelvic irradiation prior to operation, we generally observe these patients closely during the first couple of weeks of radiation as long as they do not have evidence of complete obstruction, or we divert them with a laparoscopic sigmoid colostomy. Alternatively, for a patient with widespread metastatic disease, there may not be a primary role for pelvic radiation. As the goal of radiation is usually to decrease the rates of local (pelvic) recurrence, the patient with extensive, widespread metastases may not realize this potential benefit, and often the delay in full systemic chemotherapy may not be warranted. If the metastatic disease respond to the up-front chemotherapy, there may be a subsequent role for palliative pelvic radiation or for preoperative radiation (e.g., prior to attempt at cure).

Fig. 6.8

Radiograph showing endorectal stent in place to relieve obstruction

When systemic chemotherapy is chosen as the initial approach, in some circumstances, the primary tumor shrinks considerably or even responds completely. What is the role for resection of the colon or rectum in this circumstance, and is there still a need/role for radiation in the case of a mid or low rectal cancer? Is there an indication to remove the primary source in the setting of metastatic disease? The answers to these questions are complex and need to be approached on a patient-specific basis. Sometimes these decisions are easy, such as for a patient whose primary tumor shrinks, but less significant treatment effect on the metastatic disease is observed, or who develops further metastatic disease despite ongoing chemotherapy. In these cases, there is very little, if any, role for resection of the primary tumor. However, as stated before, in a patient who has response of their liver/pulmonary disease or has disease that is resectable after up-front chemotherapy, there may well be a role in resecting the primary site of disease, especially in cases where the goal of operation is cure. Finally, there is occasionally a patient who would benefit from a palliative resection, especially in a situation where perineal pain from sphincter invasion has occurred or where the primary tumor continues to cause obstructive symptoms which are disabling.

Specific Sites of Disease

Liver

Key Concept: Metastatic disease to the liver is increasingly resected (or otherwise treated), even with bilobar involvement, based on the degree of functioning parenchyma that will remain after resection.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree