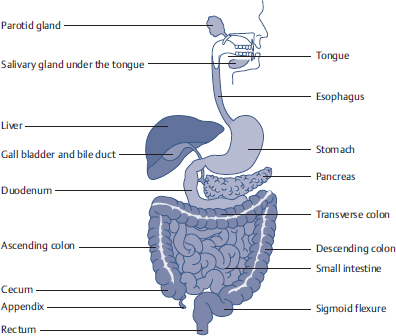

1 Illness and Health—A New View The digestive system forms the root of the human plant. A healthy digestive system is the foundation on which a healthy human being is built. Physicians such as Boerhaave, Semmelweis, and Mayr were the trailblazers of their time, who recognized the simple truths and interconnections of pathogenesis and the maintenance of health. After decades of research, Mayr established the criteria for health, which he summarized and entitled “diagnostics of good health.” ► Boerhaave. Boerhaave, the greatest physician of his day, died in 1738. During his lifetime he announced plans to bequeath the entirety of his medical knowledge to his contemporaries for the benefit of both the sick and the well. After his death, scientists from every corner of the world gathered for the sale of his sealed work. Imagine their surprise, especially the wealthy Englishman who had bought this treasure of wisdom at such a high price, when he opened its pages only to find them blank except for the following couplet penned on the last page: “Keep the head cool and warm the feet, And carefully watch how much you eat!” A joke? Hardly—rather, a golden rule for a healthy way of life, easy to understand and yet misunderstood by most. There is something peculiar about the truth: the simpler it is, the easier it is to disregard. ► Semmelweis. Around a hundred years later Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis, having discovered the cause of puerperal fever, spent the rest of his days in misery and ended up in an insane asylum! At that time almost half the mothers who had just given birth at a Viennese women’s clinic were dying from puerperal fever. Frantic efforts to discover the cause of this horrible epidemic were in vain. Semmelweis suspected that the physicians’ hands, which went from performing autopsies to treating expectant mothers, were probably not clean enough to avoid transmitting unknown toxins from the dead to the living, resulting in the abrupt end of thousands of flourishing young lives. ! Note This is a peculiar thing about the truth: the more easily it is discovered, the easier it is to dismiss. ► F. X. Mayr. The Austrian Dr. Franz Xaver Mayr, who lived in the 20 th century, put forward the novel idea that most people’s digestive systems were unclean, no longer completely efficient, and therefore unhealthy. Waste products deposited in the digestive system caused it to be contaminated, often infected, and therefore a dangerous source of toxicity. This was undermining people’s health and making them prematurely ill, old, and unattractive. Dr. Mayr insisted that people who were not completely well should thoroughly cleanse their intestines. But just like Semmelweis before him, he meant something quite different than his contemporaries. He also held that digestive systems thought to be clean and healthy were, in fact, already more or less impaired and overrun with waste deposits. How Mayr came to these conclusions is explained by his background: Around the turn of the century, Mayr was a medical student working in a sanatorium where he treated people with intestinal problems. He wondered how he would know when he had reached the goal of his treatment, that is, wellness. As he didn’t have any reliable criteria for a healthy intestinal tract or even for healthy people, he turned to the medical superintendent of the sanatorium, then to medical texts, and finally to his teachers at the university; however, none of them could provide him with answers to the following questions: • Which features can we use as a basis for forming an opinion of a person’s general state of health? • What are the properties of a healthy stomach: its size, shape, softness, and other characteristics? • Do normal, uneventful bowel movements in themselves guarantee that such a person has a healthy digestive system? • How do we recognize a digestive system in which the digestion of food is inferior, in which waste deposits are present, and in which toxic decomposition processes take place that undermine general health? The answers to these questions became the subject of a lifelong search for Mayr: He treated all his patients, regardless of whether they came to him with head, throat, lung, heart, stomach, or abdominal complaints, as though they had digestive problems. Just as Semmelweis always had examining physicians wash their hands with scrupulous thoroughness, Mayr called for meticulous cleansing of all his patients’ digestive organs, even those that seemed to be completely healthy. As a result, he came to the astonishing conclusion that even apparently healthy digestive systems are not completely healthy; in fact, some have already suffered damage (in the form of deposits). By cleansing the digestive system and returning it to health, Mayr found that most other complaints, for example, of the lungs, heart, or stomach, either abated or disappeared altogether. After decades of research, based on a unique series of examinations, and treating thousands of patients, Mayr finally established the criteria for a healthy body, which he summarized as the “diagnostics of good health.” Based on this, the following can be determined: • How far a person’s state of health deviates from his or her optimal condition. (Damage to organs, preliminary stages of illness, and previously unobserved states of illness can be objectively ascertained.) • Whether a person’s health has improved or deteriorated. • Which factors have a positive or negative influence on health. Knowledge Being Well or Being Sick Since being well or being sick—aside from genetic influences, attacks by dangerous pathogenic organisms, or other drastic factors—is mainly rooted in the way we live and eat, basic good health, which was Dr. Mayr’s goal, cannot be passively bought, for instance simply by taking pills. It unfolds gradually through the active participation of the person seeking help, because this goal can never be reached without tackling bad habits. The decision is, therefore, a moral one. Hence this path cannot be taken by those who are caught up in the pursuit of pleasure, with no self-discipline; nor by those who are hampered by lack of understanding or a “know-it-all” attitude. ! Note With this set of diagnostics Mayr established the teaching or science of wellness, which had as its goal recognizing and maintaining the best possible state of health. As medical science has always concerned itself intensely with disease, but rarely with health and healthy people, millions are spent every year on curing the sick or relieving them of specific symptoms. On the other hand, very little of a serious nature is done to prevent illness from occurring in the first place or to limit it to the erosion of vitality that is unavoidable with increasing age. Without any diagnostics for good health, many danger signs cannot be recognized and people cannot protect themselves in time. Since prevention is better than cure, Dr. Mayr’s work on maintaining wellness was significant as a basis for and complement to medical science, which until then had been oriented toward curing disease. Like Boerhaave and Semmelweis, Mayr was far ahead of his time, viewing illness and health in a new light and pointing in a new direction. Dr. Franz Xaver Mayr—Founder of the Cure Dr. Franz Xaver Mayr (1875–1965) originated the diagnostics and cure that bear his name. As a medical student, he saw that the intestines and intestinal health had not been exhaustively studied and so he began systematic investigation and research into this field. F. X. Mayr (Fig. 1.1) was born on November 28, 1875, the third child of Anton and Serafine Mayr, in the Styrian mountain town of Gröbming. His family were farmers who had lived there for centuries and he himself was close to nature from childhood. The family’s circumstances were austere and his father was very ill with tuberculosis, so the boy often had to herd the sheep instead of going to school. By the time he was 11 years old, he was going to the livestock market to buy animals from neighboring farmers. Through his critical evaluation of such indicators as coat, tongue, and teeth, he soon developed an unerring judgment of livestock health. He attended school in Graz and later studied medicine. In 1899, he was a summer intern at the St. Radegund sanatorium, where his assignment was to massage the stomachs of patients with constipation. He had heard almost nothing about this common ailment in his lectures, and the medical literature was no more informative. Mayr’s urge to engage in research was born. He found that there were fundamental gaps in the diagnostics of the abdomen and abdominal organs. In particular the small intestine, the central organ of metabolism, struck him as being diagnostically unknown territory. Research and Treatment After his graduation (1901), Mayr once more worked at St. Radegund, then later at Johannisbrunn in Troppau (Silesia) and, beginning in 1906, in Karlsbad, which was at that time the mecca for digestive diseases. There he spent decades doing fruitful work with thousands of patients. It was Mayr’s fundamental idea that none of his patients had a truly healthy intestine, and therefore he treated them all as though they had a digestive disease. Patients with and without digestive symptoms, even patients with diseases of the heart, kidneys, and joints, all received the same treatment: an intestinal respite diet, intestinal cleansing with Karlsbad water, and stimulation of the digestion by manual treatment of the abdomen. Mayr regularly recorded the size, shape, and hardness of the abdomen, its sensitivity to pressure, and the position of the intestines. Using these landmarks, he made improvements to his respite diet and his manual treatment of the abdomen. He also noted characteristic changes in the skin and posture corresponding to the status of the patient’s intestinal health. Diagnosis According to Mayr Decades of examination and treatment of many thousands of patients provided visible, palpable, measurable, and verifiable data that resulted in the development of Mayr’s own diagnostic method. This came to be known as the “diagnostics of good health” or Mayr’s diagnostics. Using his method, Mayr soon saw that in many patients he could achieve earlier and more conclusive treatment results with even stricter diets. Finally, he subjected himself to a fasting cure, in which he consumed only fresh water. The experience of the following decades convinced him that fasting is “the queen of all diets.” Development of the Milk Diet After World War II, Mayr practiced in Vienna. Since he found fasting inappropriate for people with jobs, he chose milk as a respite diet, as it is the closest to being a whole food and the easiest to metabolize. However, it is only a remedy if it is mixed, sip by sip, with saliva, as is the case with a suckling infant. Therefore, Mayr specified that it should be consumed in small spoonfuls together with an air-dried roll (cure roll), using a special technique (see p. 31). Transmission of His Knowledge From the beginning of his work as a physician, Mayr stayed informed about developments in mainstream medicine. He sought out renowned scientists at home and abroad. Later, when patients were coming to him from all over the world, he was invited to give speeches and guest lectures by various medical societies. Among his prominent patients was Chancellor Konrad Adenauer. When he was 80 years old, Mayr gave up his busy Viennese practice and retired with his wife to his home town of Gröbming. From there, he lectured to his circle of medical students founded in 1951 (Mayr Physicians’ Work Group) about the interrelation of breathing and digestion. Until his death (September 21, 1965), Mayr was always ready to share all his knowledge with interested colleagues and took a lively interest in their personal development and the growth of their knowledge. Repeatedly, he advised them to live as good examples themselves and not to be lax in their own intestinal cleansing (return to health). For, according to Mayr, “The healthier one becomes oneself, the more convinced and convincing one can be as a physician.” Illness is a drama in 10 acts: Acts 1–3 take place totally unobserved Acts 4–6 unfold in the doctor’s waiting room jammed with patients Acts 7–9 play out in the hospital And the last act occurs on the deathbed This can be confirmed from personal experience. One day you are sick from some so-called disease of civilization (e.g., rheumatism, angina pectoris, stomach ulcers or colitis, hardening of the arteries, high blood pressure, cancer, etc.), or you observe some of their symptoms (such as heartburn, a ravenous appetite, constipation, blood in the stool, tension, fatigue, insomnia, headaches, backaches or stomach pains, loss of weight, and the like), leading you naturally to think that only one specific, immediate cause (such as catching a chill, overexertion, or something lacking in your diet) is solely responsible. Since you felt fine until now and had casually boasted about never being sick a day in your life, you completely overlook the fact that the cause you are blaming for everything already represents the curtain rising on the fourth or fifth act. The previous acts have already been performed—without your knowledge. It is an undeniable fact that most human beings are no longer healthy—in the fullest sense of the word—but are at best in a state of apparent healthiness, artificially maintained. The “diagnostics of good health” describes the preliminary stages of a decline in health so that someone in apparent good health can recognize the danger signs in time, prevent their occurrence, and initiate a recovery. ! Note “It’s later than you think!” reads a sign in the waiting room of a Bavarian physician. How true. This is sometimes due to inherited organic weaknesses, predispositions, and defects, and sometimes to the habit of overloading the digestive system even in the first months of life, when most mothers believe that only eating a lot will make a baby grow big and strong. On the basis of this belief they overfeed their child; even the fully satisfied infant who has peacefully fallen asleep at the breast is awakened and encouraged to drink more—whether they believe it is in the baby’s own best interests or because it is called for in the breastfeeding schedule. Openings in the nipples of baby bottles are too large, so that instead of drinking small digestible portions, children have to gulp down large amounts of milk just to keep up with the strong flow. A baby tries vainly to defend itself by spitting up the overabundance of food. The saying, “A baby that spits up is a healthy baby,” is soon no longer applicable because vomiting and satiation reflexes don’t function anymore. Instead, the baby’s stomach gets sluggish and stretched, the excess food ferments or decomposes in its intestines and leads to a qualitatively deficient diet despite the ample intake of food. To make up for this lack its appetite often increases. The child, poorly nourished by a maternal instinct to feed, overwhelmed by parental anxiety, and a victim of old-fashioned ideas, now eats a lot and often—now he’s “a good baby.” This typical story proves that a person is not born an overeater, but is raised to be one. However, the constant pressure to eat sometimes has the opposite effect: a psychological and physical aversion to eating. The result is a thin, pale child who slumps at the table and is labeled a picky, nervous eater with no appetite. This child already suffers from considerable digestive disturbances and is frequently the object of relatives’ concern and protracted treatment by doctors. In both cases, no matter how different they may seem, the natural instinct, which should control the satisfaction of nutritional needs, is lost. Eating because food tastes good and as an end in itself, with either the quantity or a very select quality being the determining factor—without any notion of the proper amount of food—replaces this natural instinct. Very often food is then consumed only greedily and hastily, as fast as possible, or nervously and restlessly—in a rush. Attention is no longer paid to thorough chewing and salivating, which is essential for digestion. In the place of a cherished, cultivated meal in which every bite is supposed to be calmly tasted with relish and thoroughly pulverized by the teeth—hence the term “meal”—food is gulped down much too quickly. In this way it is not uncommon for “eating time” to turn into “feeding time.” However, all these sins of eating overburden the digestive organs and sooner or later cause disease. The effects then impact the entire person. The digestive system, a tube-shaped canal up to 27 feet long in adult humans, begins with the lips of the mouth and ends at the anus. It includes the oral cavity, throat, esophagus, stomach, and small and large intestines. Other glands are also part of the digestive system, including the salivary glands in the mouth, the liver and gallbladder, the pancreas, and billions of mucous glands in the stomach and intestines (see Fig. 1.2). Just as the small feeder roots of a plant absorb nourishment from the earth, producing branches, leaves, and blossom, countless intestinal villi take root in the chyme, absorbing food that has been broken down in the digestive system and supplying it to the bloodstream, which in turn carries it to all the areas that need it (the 60 trillion cells of the body). Normal digestion is achieved by the compatibility of and cooperation between all these parts. Digestion does not mean, as many think, the production of a stool, but rather the following complex processes: • The correct mechanical, chemical, and bacterial breakdown of nourishment, and its conversion into bodily substance and strength. This process includes the absorption of nutrients into the blood across an intestinal surface approximately the size of two tennis courts. • Timely elimination of unused waste products. The opposite of this normal process of digestion is the familiar process of fermentation and decay that causes disease (see p. 13). In addition to the job of nourishing the body, the digestive system serves another basic function, which Dr. Mayr was the first to point out: purification of the blood. Like waste water from a factory, metabolic refuse released by every cell in the body has to be eliminated quickly and completely. To do this, the cell discharges it into the bloodstream, which immediately carries it to the excretory organs: • The lungs exhale poisonous carbon dioxide and other gaseous waste products. • The kidneys excrete urine. • The skin eliminates waste products through cutaneous respiration and perspiration (evaporation). • The intestines purify the blood of waste matter discharged into it, which is finally eliminated in the stool (= blood purification by intestinal action). Normal, Healthy Stool The stool created by a healthy digestive system should have the following properties: • It should be sausage-shaped, with rounded ends and a smooth surface encased in a mucous sheath. • It sinks in water because it has no gaseous impurities and has only a slight characteristic odor. • It shouldn’t smell either extremely fetid or extremely acidic, which are signs of intestinal putrefaction or intestinal fermentation. • A healthy intestine evacuates the stool cleanly, which is why any noticeable soiling of the anal region is an indication of damage to the intestinal tract.

Boerhaave, Semmelweis, Mayr: Men Ahead of Their Time

These Questions Were Important for F. X. Mayr

Diagnostics of Good Health

When and How Illness Begins

How Damage First Occurs

The Digestive System—Root of the Human Plant

Normal Digestion

Purification of the Blood

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree