Prostatitis is perhaps the most common urologic complaint in men younger than 50 years of age and affects 11% to 16% of American men over the course of their lifetimes. Prostatitis syndromes have a significant psychologic impact upon patients who suffer from them and place an enormous financial strain upon the health care system. Despite many advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of prostatitis, current management strategies are unable to provide a significant portion of relief from symptoms. In this article, we focus on bacterial prostatitis (types I and II), with an emphasis on new understandings of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment strategies for these often challenging patients.

Prostatitis in all its manifestations places a significant strain on patients and urologists. It is perhaps the most common urologic complaint in men younger than 50 years of age and affects 11% to 16% of American men over the course of their lifetimes . Prostatitis syndromes have a significant psychologic impact upon patients who suffer from them and place an enormous financial strain upon the health care system . Despite many advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of prostatitis, current management strategies are unable to provide a significant portion of relief from the symptoms of prostatitis.

In the 1999 NIH consensus statement on prostatitis, prostatitis and prostatitis-like symptoms were classified into four broad categories ( Table 1 ) . Type I prostatitis refers to acute bacterial prostatitis. Type II prostatitis encompasses chronic bacterial prostatitis. Type III is the most common manifestation of the syndrome, affecting 90% of patients diagnosed with prostatitis, and is characterized by chronic pelvic pain in the absence of detectable infection. Type IV prostatitis refers to asymptomatic inflammation, found incidentally at the time of surgery, biopsy, or autopsy.

| Category I | Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| Category II | Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| Category III: chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) | Chronic pelvic pain without the presence of bacteria localized to the prostate |

| Category III a: inflammatory CPPS | Presence of significant numbers of white blood cells in expressed prostatic secretion |

| Category IIIb | Insignificant numbers of white blood cells in expressed prostatic secretion |

| Category IV: Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis | White blood cells in expressed prostatic secretion or histologic inflammation in prostatic tissue in asymptomatic individuals |

Acute bacterial prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis represent only a small proportion of prostatitis cases. Type I prostatitis is the most rare—it is diagnosed in less than 0.02% of all patients seen for prostatitis —, but the potential morbidity and mortality of acute prostatitis constitute a true urologic emergency.

Type II prostatitis affects 5% to 10% of patients who have chronic prostatitis. Many patients are diagnosed with recurrent urinary tract infections with the same organism and often have detectable pathogens in prostatic secretions during asymptomatic periods .

In this article, we focus on bacterial prostatitis (types I and II), with an emphasis on new understandings of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment strategies for these often challenging patients.

Acute bacterial prostatitis

Presentation and diagnosis

Acute bacterial prostatitis constitutes a urologic emergency. Upon presentation, patients are often acutely ill and in distress. These patients have obvious signs and symptoms of a urinary tract infection, including dysuria and urinary frequency . They often present with intense suprapubic pain, urinary obstruction, fever, malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia .

Although a gentle rectal examination can be performed in patients who have suspected acute bacterial prostatitis, prostatic massage is inadvisable because it could precipitate bacteremia or frank sepsis . Expressed prostatic secretion (EPS) or voided bladder 3 urine (VB3) are not necessary because the diagnosis can be made largely on symptomatic presentation. Although prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels are not a mainstay of diagnosis, they are generally moderately to markedly elevated in the setting of acute bacterial prostatitis .

For patients in whom a prostatic abscess is suspected, CT scan or careful transrectal ultrasound after initiation of antimicrobial therapy can aid in the diagnosis or exclusion of a prostatic abscess without increasing the risk for urosepsis .

Management

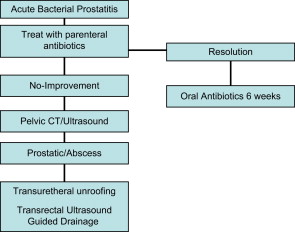

Appropriate management of acute bacterial prostatitis includes rapid initiation of broad-spectrum parenteral antibiotics and symptomatic support ( Fig. 1 ) . Typical treatment is with a penicillin or penicillin derivative, with the addition of an aminoglycoside. After successful initial therapy, patients can be transitioned to oral antibiotics (eg, fluoroquinolines), with a suggested minimum duration of three to four weeks. The long-term response is unclear. Figures of 90% have been reported , although a prospective study found a bacterial persistence rate at 3 months of 33% . Therefore, prolonged therapy of fluoroquinolines for 6 weeks and reevaluation after that has been recommended .

Because patients can have significant obstruction from an acutely inflamed prostate, bladder scanning for postvoid residual urine is recommended. If the residual urine is less than 100 mL, the patient should be initiated on alpha blocker therapy; if the residual is large, consideration should be given to placement of a small urethral catheter if short-term drainage is required or a suprapubic catheter if longer-term drainage is required . Stool softeners are also recommended .

Special considerations for the immunocompromised patient

Patients who are immunocompromised, especially patients who have HIV/AIDS, seem to be more susceptible to the development of acute bacterial prostatitis and to the occurrence of a potentially life-threatening prostatic abscess . Although the incidence of acute prostatitis in patients who have well controlled HIV is roughly equivalent to that of the general noncompromised population, the incidence rate rises to roughly 14% in those who have developed AIDS . However, these data are quite old. Original studies updating these data during the last 8 years are lacking, and all current references refer back to the 1989 report . It is these authors’ impression that current rates are lower. If a prostatic abscess is discovered, initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotics and prompt surgical drainage is crucial.

Prostatic abscess

Prostatic abscesses are uncommon but potentially serious manifestations of acute infection of the prostate and demand prompt treatment. Patients who have a prostatic abscess are commonly immunocompromised or diabetic and typically present in a similar fashion to patients who have acute bacterial prostatitis without abscess, although unusual presentations do occur, as illustrated by a patient who presented with priapism . Although CT and MRI are effective modalities for the diagnosis of prostatic abscess, transrectal ultrasound has been increasingly recommended due to its high sensitivity, greater cost-effectiveness, and ability to provide diagnosis and directed treatment in a single procedure, with CT being used primarily in cases where the transrectal ultrasound is nondiagnostic or suggestive of more extensive involvement .

Recommended treatment consists of broad-spectrum antibiotic coverage and, in most cases, drainage of the abscess. Although transurethral unroofing and perineal drainage were once the mainstays of surgical drainage, transrectal ultrasound-guided aspiration of prostatic abscesses has been increasingly used as an effective means of drainage that may avoid the potential morbidity associated with transurethral drainage . Some authors also support urinary diversion with a suprapubic catheter .

Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus species are the most commonly isolated pathogens in prostatic abscess, although other pathogens, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis , Actinomyces, Citrobacter, Bacteroides fragilis , Aeromonas aerophyla , and Klebsiella pneumonia have been reported . Burkholderia pseudomallei overwhelmingly predominates in the Thai population .

Postbiopsy prostatitis

One of the most serious complications of transrectal biopsy of the prostate is the development of postbiopsy prostatitis and septicemia. Although these complications are rare, the severity of symptoms often necessitates an inpatient admission for administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics.

Bacteremia is common after prostate biopsy. A recent report found bacteremia in 44% patients undergoing transrectal biopsy without preprocedural antibiotics . With proper antibiotic prophylaxis, generally with a single dose of a fluoroquinoline, infectious complications are likely to develop in only 1% to 2% of patients undergoing transrectal biopsy . Studies also demonstrated no difference in efficacy between single-dose antibiotics given 2 hours before or at the time of biopsy . Factors that increase the likelihood of infectious complications are the presence of an indwelling catheter and bactiuria at the time of biopsy .

It is generally agreed that antibiotic prophylaxis before biopsy is warranted, although the timing may not be critical. In addition, one study found that postbiopsy administration, although not recommended, is effective in preventing infectious complications . The role of prebiopsy enema is a matter of debate. Although the data are mixed, the preponderance of evidence suggests that a prebiopsy enema is not beneficial when patients are given preprocedural antibiotics .

In the small proportion of patients who have no contraindication to biopsy in whom infectious complications develop despite antibiotic prophylaxis, resistant bacterial strains are a likely culprit. Of growing importance are multidrug resistant strains of E coli that escape traditional quinolone therapy. Known risk factors for colonization with resistant strains of E coli are age, travel to developing countries, and, most importantly, prior exposure to quinolones . A case study found resistant strains of Klebsiella and Pseudomonas in a patient who developed multisystem organ failure after prostate biopsy .

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Presentation

Classically, chronic bacterial prostatitis presents as recurrent urinary tract infection, usually with the same organism. Patients are not ill appearing but may complain of irritative voiding symptoms and testicular, lower back, or perineal discomfort . On examination, the prostate may be palpably normal but may also have appreciable bogginess or tenderness . Of patients who have chronic prostatitis, only 5% to 10% have evidence of infection .

Between episodes of urinary tract infection, bacterial infection in chronic bacterial prostatitis can be localized to the prostate, indicating ongoing prostatic infection . Localization, historically, has involved the collection of multiple urine samples and expressed prostatic secretions to pinpoint the source of bacteria in patients who have prostatitis. Most urologists rely upon simplified diagnostic measures to localize bacteria in the urinary tract .

The four-glass versus the two-glass test

Classically, the diagnosis of prostatitis has hinged upon the gold-standard four-glass test, initially described by Mears and Stamey . The four-glass test involves collection of distinct specimens, each designed to localize inflammation and infection to a distinct portion of the urinary tract. The VB1 specimen, or the initial 10 mL voided volume, localizes the urethra and can detect urethral colonization. The VB2 specimen corresponds to the standard midstream specimen and localizes to the bladder. The final two specimens are designed to directly examine the prostatic contents. For the third specimen, prostatic massage is performed, and the EPS are collected. Finally, the VB3, which is the first 10 mL of voided volume after prostatic massage, is collected; this specimen likely includes EPS that remains in the urethra after prostatic massage.

Few urologists perform the four-glass test, instead relying upon a two-glass test comprised of a midstream specimen and a postmassage specimen corresponding to the VB2 and VB3 portions of the four-glass test, respectively. A survey of urologists found that few urologists (<20%) perform the standard four-glass test, with few attempting to obtain EPS samples. Moreover, a majority of urologists treat all forms of prostatitis empirically with antibiotics without performing a complete diagnostic test . This has led to increased scrutiny of the “standard” diagnostic methods for prostatitis and to closer inspection of the necessity and practicality of performing the four-glass test.

A direct comparison of the sensitivity of the standard four-glass test compared with the two-glass test found the two-glass test to be 96% to 98% as accurate as the four-glass test, with the VB3 specimen failing to predict positive EPS specimens in a small number of patients . Therefore, it could be argued based upon this evidence that the two-glass test is emerging as the appropriate new standard of evaluation.

One study has identified an alternate “two-glass” evaluation using VB1 samples combined with semen culture . The authors note that semen culture is more sensitive than EPS in identifying gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, and semen sample collection forgoes potentially unnecessary discomfort associated with collection of VB3 or EPS through prostatic massage. In this study, gram-positive localization was highly inconsistent. An overall comparison of techniques is illustrated in Table 2 .

| Mears-Stamey | Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network Study Group (CPCRN) | Budia | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voided bladder 1 (initial stream urine culture) | X | – | X |

| Voided bladder 2 (mid-stream urine culture) | X | X | |

| Expressed prostatic secretion (culture) | X | – | |

| Voided bladder 3 post-prostatic massage culture (10 mL) | X | X | |

| Semen culture | – | – | X |

| Benefits of technique | Gold standard | 46% concordance with Mears-Stamey | Possibly 15% more accurate than CPCRN technique |

| Expensive | Cheaper | Cheaper |

Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Presentation

Classically, chronic bacterial prostatitis presents as recurrent urinary tract infection, usually with the same organism. Patients are not ill appearing but may complain of irritative voiding symptoms and testicular, lower back, or perineal discomfort . On examination, the prostate may be palpably normal but may also have appreciable bogginess or tenderness . Of patients who have chronic prostatitis, only 5% to 10% have evidence of infection .

Between episodes of urinary tract infection, bacterial infection in chronic bacterial prostatitis can be localized to the prostate, indicating ongoing prostatic infection . Localization, historically, has involved the collection of multiple urine samples and expressed prostatic secretions to pinpoint the source of bacteria in patients who have prostatitis. Most urologists rely upon simplified diagnostic measures to localize bacteria in the urinary tract .

The four-glass versus the two-glass test

Classically, the diagnosis of prostatitis has hinged upon the gold-standard four-glass test, initially described by Mears and Stamey . The four-glass test involves collection of distinct specimens, each designed to localize inflammation and infection to a distinct portion of the urinary tract. The VB1 specimen, or the initial 10 mL voided volume, localizes the urethra and can detect urethral colonization. The VB2 specimen corresponds to the standard midstream specimen and localizes to the bladder. The final two specimens are designed to directly examine the prostatic contents. For the third specimen, prostatic massage is performed, and the EPS are collected. Finally, the VB3, which is the first 10 mL of voided volume after prostatic massage, is collected; this specimen likely includes EPS that remains in the urethra after prostatic massage.

Few urologists perform the four-glass test, instead relying upon a two-glass test comprised of a midstream specimen and a postmassage specimen corresponding to the VB2 and VB3 portions of the four-glass test, respectively. A survey of urologists found that few urologists (<20%) perform the standard four-glass test, with few attempting to obtain EPS samples. Moreover, a majority of urologists treat all forms of prostatitis empirically with antibiotics without performing a complete diagnostic test . This has led to increased scrutiny of the “standard” diagnostic methods for prostatitis and to closer inspection of the necessity and practicality of performing the four-glass test.

A direct comparison of the sensitivity of the standard four-glass test compared with the two-glass test found the two-glass test to be 96% to 98% as accurate as the four-glass test, with the VB3 specimen failing to predict positive EPS specimens in a small number of patients . Therefore, it could be argued based upon this evidence that the two-glass test is emerging as the appropriate new standard of evaluation.

One study has identified an alternate “two-glass” evaluation using VB1 samples combined with semen culture . The authors note that semen culture is more sensitive than EPS in identifying gram-negative and gram-positive organisms, and semen sample collection forgoes potentially unnecessary discomfort associated with collection of VB3 or EPS through prostatic massage. In this study, gram-positive localization was highly inconsistent. An overall comparison of techniques is illustrated in Table 2 .