Women’s Health and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Nissrin M. Ezmerli

Aline Charabaty

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) affect 1 million people in the United States, and most of these patients are at the peak of their reproductive years. This demographic raises particular issues related to women’s health, such as sexuality, body image, contraception, fertility, and pregnancy. In this chapter we will review these topics with a primary focus on the treatment of IBD during pregnancy and lactation.

SEXUALITY

The diagnosis of IBD generally occurs at a time when young people are dealing with body image, interpersonal relationships, and sexuality issues. The disease itself can directly interfere with a woman’s desire and capacity to establish and maintain an intimate relationship. One study interviewed 50 women with Crohn’s disease (CD), 45 of whom were in a stable relationship, regarding their sexual activity. Twenty-four percent of women with CD reported infrequent or no intercourse in comparison to 4% of women in the control group (1). The main concerns expressed by the women with CD were abdominal pain, fear of fecal incontinence, and diarrhea (2,3). Complications of perforating CD (enterocutaneous fistulas, perianal disease, enterovaginal fistula) can negatively impact body image and self-confidence in women, as well as cause embarrassment, fear of intimacy, and discomfort during sexual intercourse.

Treatment of IBD (medications, mainly steroids and surgery) can indirectly interfere with a woman’s sexuality. Women often complain of the side effects of steroids on their physical appearance (weight gain, acne, striae) and their emotional well-being (irritability, insomnia, emotional lability, depression) and, consequently, of the negative impact on their body image and relationships. Surgical treatment of IBD can have positive or negative effects on a woman’s sexuality, depending on the end result. Patients who undergo colectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA) usually have improved body image, decreased fear of incontinence, and resume sexual activity soon after surgery.

It is important to realize that women often do not bring up topics related to their personal and private life to their physician and it should be incumbent on the practitioner to establish trust and to initiate an open conversation with the patient. If necessary/when appropriate, referral to sex therapists, ostomy nurses, support groups, and mental health specialists should be made.

CERVICAL CANCER RISK

Increasingly, data have demonstrated that women with IBD have a higher incidence of abnormal Pap smears compared to the general population. In a study by Bhatia et al., 18% of 116 patients with IBD had an abnormal Pap smear compared to 5% of the 116 matched controls (4). There was no difference in the number of abnormal Pap smears based on disease type (CD or UC) or on the concomitant use of immunosuppressive medications (4). However, recently Kane et al. looked at 40 women with

IBD (8 UC patients, 32 CD patients) and compared them to matched controls (5). The incidence of abnormal Pap smears in women with IBD compared to controls was 42.5% versus 7%, with women who had been exposed to immunomodulators being at the highest risk. In addition, there was an increased incidence of highergrade lesions in women with IBD, and all specimens were human papillomavirus (HPV) serotype 16 or 18. In light of these findings, the authors recommend that women with IBD be included in the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology screening guidelines for immunocompromised individuals and undergo annual Pap smears. Furthermore, with the recent approval of Gardasil (the first vaccine for cervical cancer induced by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18), we should consider offering vaccination to IBD women regardless of their sexual activity and previous Pap smear history.

IBD (8 UC patients, 32 CD patients) and compared them to matched controls (5). The incidence of abnormal Pap smears in women with IBD compared to controls was 42.5% versus 7%, with women who had been exposed to immunomodulators being at the highest risk. In addition, there was an increased incidence of highergrade lesions in women with IBD, and all specimens were human papillomavirus (HPV) serotype 16 or 18. In light of these findings, the authors recommend that women with IBD be included in the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology screening guidelines for immunocompromised individuals and undergo annual Pap smears. Furthermore, with the recent approval of Gardasil (the first vaccine for cervical cancer induced by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18), we should consider offering vaccination to IBD women regardless of their sexual activity and previous Pap smear history.

FERTILITY

The overall fertility rate in women with IBD is similar to that in matched controls. However, there is often voluntary childlessness mainly because of the fear of transmitting the disease to the offspring and because of decreased sexual activity from fear of intimacy and dyspareunia as discussed above (6,7). Certain disease factors can decrease fertility in IBD patients: active disease in the colon, the presence of postinflammatory scar tissue, or postsurgical adhesions involving the fallopian tubes or ovaries (7,8).

Some medications affect fertility in male patients with IBD. Sulfasalazine causes a reversible decrease in sperm count and motility in men (9). Men planning for a family should discontinue sulfasalazine and/or be switched to mesalamine 3 months prior to conception. Methotrexate (MTX) can also cause reversible male infertility and should be discontinued for at least 3 months before conception is attempted. Infliximab in men may decrease sperm motility and the number of normal oval forms. It is unclear whether these changes translate into impaired fertility (10).

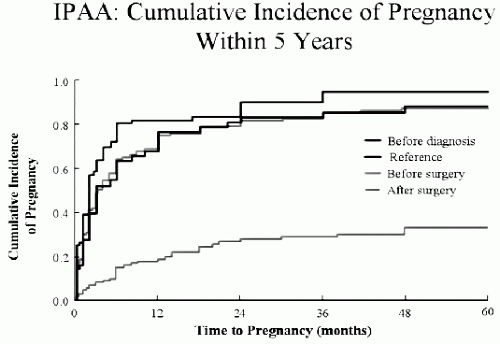

In addition, there is an 80% drop in the ability to conceive in female UC patients after total colectomy and IPAA (11,12). This impact on fertility is a very important issue to discuss with young female patients when considering surgery, with the knowledge that most patients will be able to conceive by artificial means (see Fig. 19.1). A similar increase in infertility is seen in women with CD who underwent surgery for their disease compared to women who did not (12% vs. 5%) (7). Use of antiadhesive gels to reduce postsurgical adhesions should be considered in IBD patients undergoing surgery in hopes of improving their fecundibility.

One of the first questions women ask when discussing pregnancy is whether or not the disease will be transmitted to a child. Although a family history of IBD is a major risk factor for developing IBD, the risk is still low since the disease is not transmitted in a Mendelian fashion. The lifetime risk of developing IBD is 5% to 10% if a parent has CD and 2% to 4% if a parent has UC, with the risk being highest in Jewish families compared to non-Jewish families. The lifetime risk of developing IBD goes up to 37% if both parents have IBD.

There are no guidelines regarding which method of contraception is best suited for female IBD patients. Use of an intrauterine device (IUD) can create a diagnostic dilemma if the patient develops abdominal pain (pelvic inflammatory disease or IBD flare-up). Oral contraceptive (OC) use is controversial in IBD. A European study showed an increased risk of CD in women on OC, whereas in the United States there are no data linking OC use and IBD incidence. This variation might be related to the higher estrogen content in OC in Europe. Other concerns regarding the use of OC are the risk of precipitating a Crohn’s flare and unmasking an IBD-associated hypercoagulable state. On the other hand, some studies suggest an association between phases of the menstrual cycle and disease activity, which is

thought to be related to fluctuations in hormonal levels. Women whose Crohn’s symptoms seem to be exacerbated during their menstrual cycle might benefit from OC use to stabilize their disease. In any case, it is preferable to use an OC formulation with a low estrogen amount.

thought to be related to fluctuations in hormonal levels. Women whose Crohn’s symptoms seem to be exacerbated during their menstrual cycle might benefit from OC use to stabilize their disease. In any case, it is preferable to use an OC formulation with a low estrogen amount.

PREGNANCY

Women with IBD should be able to have/anticipate healthy, uneventful pregnancies. The most important factor for a good pregnancy outcome is inactive disease. Specifically, a woman should be in remission for at least 3 months before conception and maintain remission during pregnancy. The rate of relapse in pregnant women with inactive disease is similar to the rate of relapse in nonpregnant women at 9 months (around 30%) (13). However, if the disease is active at the time of pregnancy, up to 70% of women will experience persistent or worsening disease activity. Active disease at conception increases the risk of fetal loss, and a flare during pregnancy increases the risk of a low birth weight infant and premature birth (14,15). Conversely, multiple studies have shown that women with inactive IBD are not at increased risk for spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or children with congenital abnormality when compared to the general population (13,15). In light of the available data, physicians should emphasize to IBD-affected women the importance of conceiving when their disease is in remission and to stay on their maintenance treatment during pregnancy. This being said, some studies suggest that IBD is an independent risk factor for negative pregnancy outcomes. A population-based study by Dominitiz et al. (16) showed that infants born to women with CD are at increased risk for preterm birth, low birth weight, and being small for gestational age, whereas infants born to women with UC are at increased risk for congenital malformations

compared to the general population. However, this study did not adjust for disease activity and medication use during pregnancy. In a large Danish cohort study by Norgard et al., there was no overall increase in congenital anomalies in infants born to mothers with UC compared to matched controls (17). When the authors looked at specific anomalies (limb deficiency, obstructive urinary congenital abnormalities, and multiple congenital abnormalities), they noted that these were slightly increased in the offspring of UC women (17). In a more recent cohort study in the United States, Mahadevan et al. found that women with IBD are less likely to have live births and more likely to have spontaneous abortions and pregnancy complications, independent of disease activity and medication use (although few patients in this study were on immunomodulators or biologics) (18). However, there was no increase in congenital anomalies in infants born to women with IBD. All this taken together, it is recommended that pregnant women with IBD be followed by high-risk obstetricians.

compared to the general population. However, this study did not adjust for disease activity and medication use during pregnancy. In a large Danish cohort study by Norgard et al., there was no overall increase in congenital anomalies in infants born to mothers with UC compared to matched controls (17). When the authors looked at specific anomalies (limb deficiency, obstructive urinary congenital abnormalities, and multiple congenital abnormalities), they noted that these were slightly increased in the offspring of UC women (17). In a more recent cohort study in the United States, Mahadevan et al. found that women with IBD are less likely to have live births and more likely to have spontaneous abortions and pregnancy complications, independent of disease activity and medication use (although few patients in this study were on immunomodulators or biologics) (18). However, there was no increase in congenital anomalies in infants born to women with IBD. All this taken together, it is recommended that pregnant women with IBD be followed by high-risk obstetricians.

There are few studies that have looked at the effect of pregnancy on the overall disease course. Data suggest that there is a decreased need for surgery in women with CD who had gone through pregnancies compared to nulliparous patients, and a lower relapse rate in women with CD in the years following their pregnancy compared to before pregnancy (19). There is often concern about the effect of pregnancy on women who have had surgery for IBD. Women with a stoma can develop prolapse of the stoma because of increased abdominal pressure, but this does not affect stomal function and generally does not lead to complications. Women with IPAA can experience an increase in stool frequency and stool incontinence, but these symptoms resolve after delivery. A small case series by Scott et al. concluded that pregnancy and vaginal delivery are safe in women with IPAA (20).

TREATMENT OF IBD DURING PREGNANCY

The most important factor that affects pregnancy outcomes in women with IBD is the degree of disease activity in the months preceding and during the pregnancy. The optimal time for a patient to get pregnant is when the disease is quiescent. It is crucial for the patient to remain on the drugs that helped her achieve remission to better ensure that the disease will remain inactive throughout the pregnancy. Most IBD drugs are safe during pregnancy and the greatest risk during pregnancy does not come from the drugs but from active disease (Table 19.1). Many women and gynecologists are apprehensive about medications during pregnancy, and patients often discontinue the IBD drugs on their own (or following a physician’s instructions to do so) when they learn of their pregnancy. Hence, it is important for the treating gastroenterologist to have a discussion with the patient and her gynecologist about

the importance of staying on the IBD drugs that are deemed safe and keeping the disease inactive before conception occurs. It is recommended that this discussion be repeated during the pregnancy to ensure compliance with the treatment during that time.

the importance of staying on the IBD drugs that are deemed safe and keeping the disease inactive before conception occurs. It is recommended that this discussion be repeated during the pregnancy to ensure compliance with the treatment during that time.

TABLE 19.1 Summary of Drugs’ Safety During Pregnancy | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

5-Aminosalicylic Acid Preparations

All 5-ASA products (sulfasalazine, mesalamine, and balsalazide) are Pregnancy Category B, except for olsalazine which is Pregnancy Category C. There were some initial case reports describing congenital malformations with the use of 5-ASA compounds. However, large case series and population-based studies did not find an increased risk of congenital abnormalities in the offspring of women who took 5-ASA during pregnancy (21). There are data to suggest an increased risk of premature birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth when women used mesalamine during pregnancy, but these events occurred mainly in women with active disease or who were on multiple drugs for their IBD during pregnancy (22,23). Hence, these complications could be the result of the disease process itself and not a side effect of the drug. Cohort studies have shown that the use of sulfasalazine or mesalamine during pregnancy does not increase the risk of birth defects, spontaneous abortions, or premature delivery (24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree