(1)

Department of Vascular Surgery, Evangelisches Krankenhaus Königin Elisabeth Herzberge, Berlin, Germany

Stenoses and/or occlusions of the venous runoff do not automatically cause thrombosis of the AV access. If there are venous side branches distal to the occlusion whose valves do not function properly, venous drainage is still possible via these collaterals. Regarding these collaterals, there are two clinical entities:

Venous congestive syndrome

Syndrome of retrograde venous arterialization

The impressive and unique clinical presentation already allows for a quick visual diagnosis.

8.1 Venous Congestive Syndrome

8.1.1 Pathophysiology

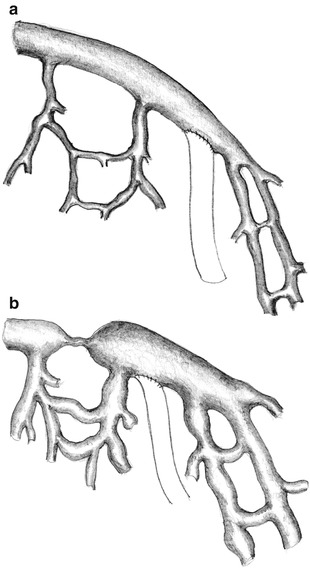

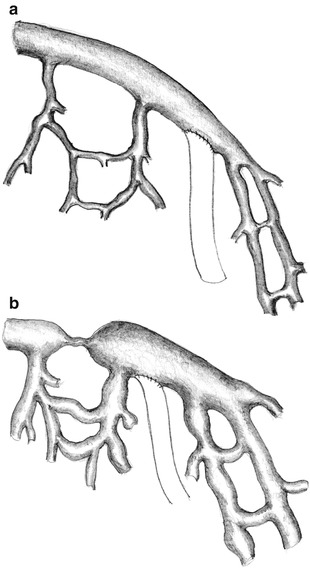

With a proximal venous stenosis or occlusion, proximal venous drainage of an AV shunt is maintained by a web of (varying) large or medium size collateral veins (Fig. 8.1).

Fig. 8.1

Pre-existing venous collaterals (a) are more pronounced with venous congestion (b)

Because of the increased resistance in these collaterals, the raised pressure impairs drainage from the extremity. Therefore in the respective extremity, there will be:

Numerous enlarged veins

Venous edema

Worsening of the edema by secondary decompensation of the lymphatic drainage

The clinical presentation depends on the site of the occlusion, shunt flow, collaterals, and duration.

Obligatory (varying) signs include:

Prominent, bulging subcutaneous veins

Bluish, livid discoloration of the skin

Edema of the extremity

Optional signs are:

Lymph edema

Pain

Hemosiderin deposits in the skin

A decreased range of motion of the joints

Indication

We see an indication for treatment if:

The function of the AV access is at risk

Patients suffer

Frequently wait-and-see is a valid tactic, as clinical symptoms decrease with the formation of further effective collaterals. Sometimes we merely perform flow reduction when there is:

A high flow AV access

No way to improve venous drainage

Only limited options for other new potential vascular accesses

8.1.2 Occlusions/Stenoses of the Forearm Cephalic Veins with Distal AV Anastomoses

Clinical features distal to the occlusion may be discrete (Fig. 8.2). Collateral drainage mostly happens into the basilic veins, or less often into deep veins.

Fig. 8.2

Venous congestion. Edema of the hand after distal cephalic fistula with occlusion of the cephalic vein in the middle of the forearm

Therapy

The whole armamentarium of endovascular (PTA/stenting) and surgical techniques may be used for short stenoses or occlusions. Long occlusions require a prosthetic graft to a suitable proximal vein for improved drainage. Rarely the basilic vein may be used for puncture after its arterialization via a side branch of the cephalic vein.

8.1.3 Occlusions/Stenoses of the Cubital Veins with Distal AV Anastomoses

Clinical features are usually more pronounced (Fig. 8.3). They generally involve the whole forearm. Collaterals drain into the basilic vein and deep veins, and seldom into the cephalic vein. We have witnessed the development of chronic lymph edema with secondary changes several times (Fig. 8.4).