The main problems associated with venous catheters are infection, poor flow, thrombosis, and central venous stenosis.

I. INFECTION. Despite the best practices detailed in Chapter 7 (Table 7.3), infections do occur with venous catheters, and at a rate substantially higher than with arteriovenous (AV) fistulas. Infection is the leading cause of catheter loss and increases morbidity and mortality. Most often, infection results from contamination of the catheter connectors or from lumen contamination during dialysis or from infused solutions. Infection also may arise from the migration of the patient’s own skin flora through the puncture site and onto the outer catheter surface. Catheters can sometimes become colonized from more remote sites during bacteremia.

A. Exit-site infection can be diagnosed when there is erythema, discharge, crusting, and tenderness at the skin exit site, but no tunnel tenderness or purulence. Treatment with topical antibiotic cream and oral antibiotics may be sufficient. These infections can be prevented by meticulous exit-site care. The patient should be investigated for nasal carriage of Staphylococcus and if present, treated with intranasal mupirocin cream (half tube twice a day to each nostril for 5 days) to prevent future infections. With exit-site infection, the catheter must be removed if systemic signs of infection develop (leukocytosis or temperature >38°C), if pus can be expressed from the track of the catheter, or if the infection persists or recurs after an initial course of antibiotics. If blood cultures are positive, then the catheter should be removed.

B. Tunnel infection is infection along the subcutaneous tunnel extending proximal to the cuff toward the insertion site and venotomy. Typically, there is marked tenderness, swelling, and erythema along the catheter tract in association with purulent drainage from the exit site. This can result in systemic bacteremia. In the presence of drainage or signs of systemic infection, the catheter should be removed immediately and antibiotic therapy prescribed.

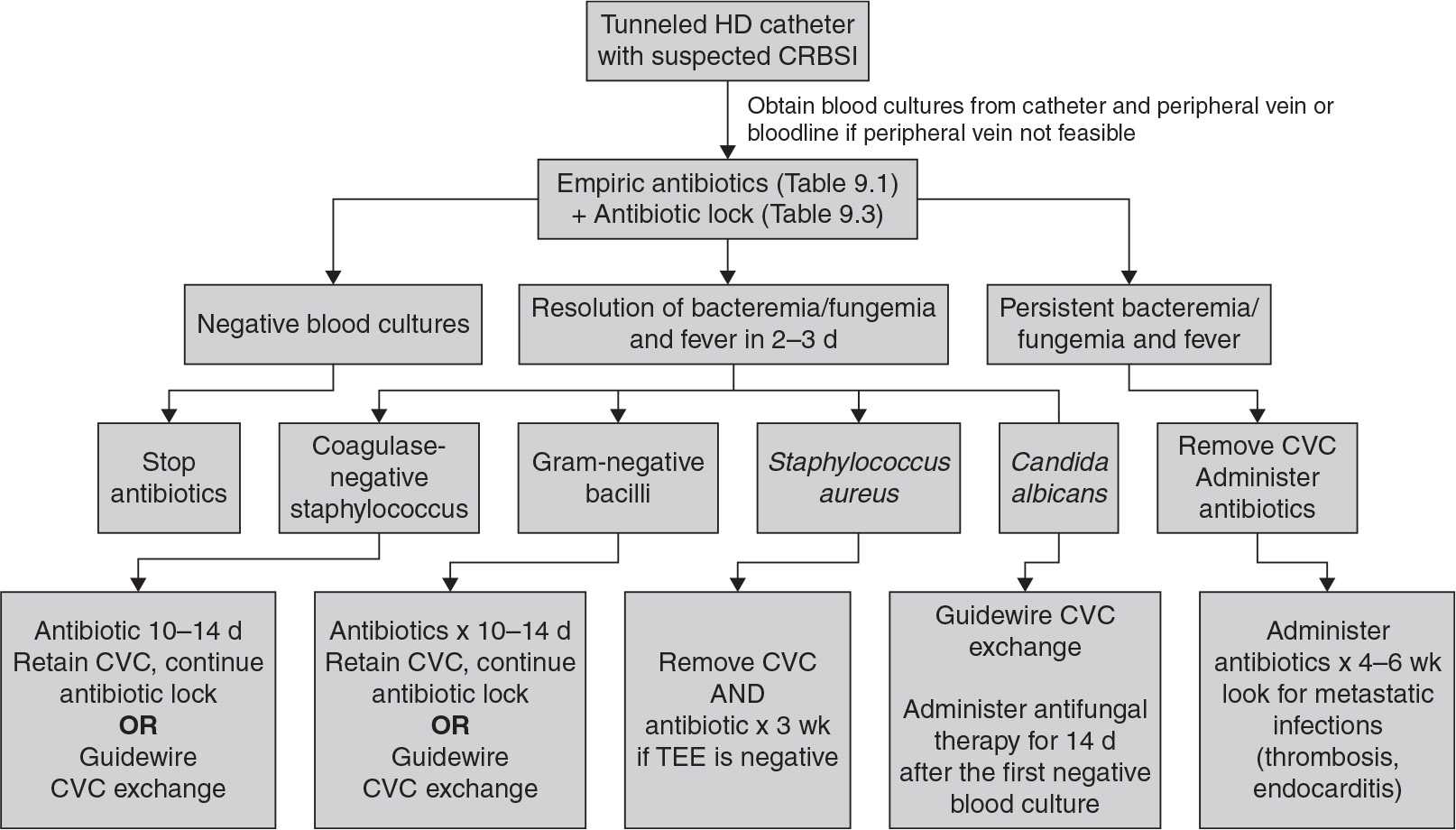

C. Catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI). Patients present with signs and symptoms of systemic infection, which may range from minimal to severe. Milder cases present with fever or chills, whereas more severe cases exhibit hemodynamic instability. Patients may develop septic symptoms after initiation of dialysis, suggesting systemic release of bacteria and/or endotoxin from the catheter. There can be signs of metastatic infection, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, epidural abscess, and septic arthritis. Gram-positive organisms are the causative organisms in the majority of cases, but gram-negative infections occur in a very sizeable minority. For details on how to treat CRBSI in dialysis patients, caregivers can refer to valuable information available on the dialysis section of the U.S. Centers of Disease Control (CDC) website (http://www.cdc.gov/dialysis), the NKF KDOQI 2006 vascular access guidelines (NKF, 2006), the European Renal Best Practices (ERBP) access guidelines (Tordoir, 2007), the Infectious Disease Society of North America (IDSA) guidelines update for management of CRBSI (Mermel, 2009), and the ERBP commentary on the IDSA guidelines (Vanholder, 2010). Treatment algorithms and tips from the IDSA are reproduced in Figure 9.1 and Tables 9.1 and 9.2, and key recommendations from the ERBP are shown in Figure 9.2.

The principles of CRBSI management in dialysis patients are different from the infectious disease guidelines for treatment of infection in short-term central venous catheters. In hemodialysis, the venous catheter is a lifeline that sometimes can be replaced only with great difficulty. Thus, the guidelines include a variety of catheter salvage maneuvers, which involve use of antibiotic-containing catheter locks or replacing the infected catheter with a new catheter in the same location over a guidewire. However, these catheter salvage techniques should be used only in limited, defined circumstances. If a patient’s condition worsens after a relatively short trial of catheter salvage, the catheter must be removed to minimize the risk of spreading the infection to body organs.

1. Blood and catheter tip cultures. In working up a suspected CRBSI, cultures can be obtained from the catheter hub, from a peripheral vein, or from the blood lines during dialysis treatment. The IDSA recommendations are to take blood cultures from a catheter hub and from a peripheral vein and, when a catheter has been removed because of suspicion of infection, to also culture the distal 5 cm of its tip. One is looking for both blood cultures or for both the blood culture and a catheter tip culture to be positive with the same organism to confirm a diagnosis of CRBSI. When taking cultures from the skin or from a catheter hub, the IDSA recommends cleaning and sterilizing the area with alcoholic chlorhexidine rather than povidone-iodine, and allowing the antiseptic to dry before sampling; this avoids contamination of the cultured material with liquid antiseptic. The IDSA guidelines recognize that obtaining blood from the dialysis bloodline is an acceptable substitute for peripheral blood cultures in many hemodialysis patients.

FIGURE 9.1 Pathway for treatment of cuffed hemodialysis catheter infections according to the Infectious Disease Society of America, 2009 Update. HD, hemodialysis; CVC, central venous (dialysis) catheter; TEE, transesophageal echocardiography. (Reproduced with permission from Mermel LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45.)

Antibiotic Dosing for Patients Who Are Undergoing Hemodialysis | |

Empirical Antibiotic Dosing Pending Culture Results

Vancomycin plus empirical gram-negative rod coverage based on local antibiogram data

OR

Vancomycin plus gentamicin

Typical doses: (Doses need to be adjusted for residual renal function and for enhanced dialytic removal in case of frequent or extended dialysis, very high efficiency, high-flux treatments, or hemodiafiltration. Monitor predialysis trough levels if possible

(Cefazolin may be used in place of vancomycin in units with a low prevalence of methicillin-resistant staphylococci)

Vancomycin: 20-mg/kg loading dose infused during the last hour of the dialysis session, and then 500 mg during the last 30 min of each subsequent dialysis session

Gentamicin (or tobramycin): 1 mg/kg, not to exceed 100 mg after each dialysis session

Ceftazidime: 1 g iv after each dialysis session

Cefazolin: 20 mg/kg iv after each dialysis session

For Candida Infection

An echinocandin (caspofungin 70 mg iv loading dose followed by 50 mg iv daily; intravenous micafungin 100 mg iv daily; or anidulafungin 200 mg iv loading dose, followed by 100 mg iv daily); fluconazole (200 mg orally daily); or amphotericin B

iv, intravenous.

Adapted from Mermel LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intravascular catheter-related infection: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1–45, with permission.

The ERBP ad hoc advisory recommendations are similar to what the IDSA recommends. They too, recognize the difficulties in obtaining cultures from peripheral veins in hemodialysis patients, and believe that a practical alternative is to simply draw blood cultures from the dialysis circuit. Blood from the circuit during dialysis probably represents peripheral blood rather than localized catheter blood, and so a positive blood culture drawn from the bloodline may reflect a source of bacteremia other than at the catheter. The ERBP group suggests that the best way to deal with this possibility is by evaluating clinical history, examination, imaging, and targeted laboratory testing, including urine culture if possible.

2. Indications for immediate catheter removal. If there is evidence of septic thrombosis, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis, or of severe sepsis with hypotension, then the dialysis catheter needs to be removed immediately. The same recommendation generally holds for tunnel infection with fever. Dialysis should be continued with a temporary catheter inserted at a different location.

Unique Aspects of Managing Patients Receiving Hemodialysis through Catheters for Whom Catheter-Related Infection Is Suspected or Proven | |

Blood and Catheter Cultures

Peripheral blood samples should be obtained for culture from vessels that are not intended for future use in creating a dialysis fistula (e.g., hand veins).

When a peripheral blood sample cannot be obtained, blood samples may be drawn during hemodialysis from bloodlines connected to the dialysis catheter.

In patients with suspected CRBSI for whom blood cultures have been obtained and for whom antibiotic therapy has been initiated, antibiotic therapy can be discontinued if both sets of blood cultures have negative results and no other source of infection is identified.

When a peripheral blood sample cannot be obtained, no other catheter is in place from which to obtain an additional blood sample, there is no drainage from the insertion site available for culture, and there is no clinical evidence for an alternate source of infection, then positive results of culture performed on a blood sample obtained from a catheter should lead to continuation of antimicrobial therapy for possible CRBSI in a symptomatic hemodialysis patient.

Catheter Removal, Change, and Salvage with Antimicrobial Lock

The infected catheter should always be removed for patients with hemodialysis CRBSI due to S. aureus, Pseudomonas sp., or Candida sp. and a temporary (nontunneled catheter) should be inserted into another anatomical site. If absolutely no alternative sites are available for catheter insertion, then exchange the infected catheter over a guidewire.

When a hemodialysis catheter is removed for CRBSI, a long-term hemodialysis catheter can be placed once blood cultures with negative results are obtained.

For hemodialysis CRBSI due to other pathogens (e.g., gram-negative bacilli other than Pseudomonas sp. or coagulase-negative staphylococci), a patient can initiate empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy without immediate catheter removal. If the symptoms persist or if there is evidence of a metastatic infection, the catheter should be removed. If the symptoms that prompted initiation of antibiotic therapy (fever, chills, hemodynamic instability, or altered mental status) resolve within 2–3 d and there is no metastatic infection, then the infected catheter can be exchanged over a guidewire for a new, long-term hemodialysis catheter.

Alternatively, for patients for whom catheter removal is not indicated (i.e., those with resolution of symptoms and bacteremia within 2–3 d after initiation of systemic antibiotics and an absence of metastatic infection), the catheter can be retained, and an antibiotic lock can be used as adjunctive therapy after each dialysis session for 10–14 d.

Antibiotic Therapy

Empirical antibiotic therapy should include vancomycin and coverage for gram-negative bacilli, based on the local antibiogram (e.g., third-generation cephalosporin, carbapenem, or beta-lactam/beta-lactamase combination)

Patients who receive empirical vancomycin and who are found to have CRBSI due to methicillin-susceptible S. aureus should be switched to cefazolin. For cefazolin, use a dosage of 20 mg/kg (actual body weight), rounded to the nearest 500-mg increment, after dialysis.

A 4–6-wk antibiotic course should be administered if there is persistent bacteremia or fungemia (i.e., 172 hr in duration) after hemodialysis catheter removal or for patients with endocarditis or suppurative thrombophlebitis, and 6–8 wk of therapy should be administered for the treatment of osteomyelitis in adults.

Patients receiving dialysis who have CRBSI due to vancomycin-resistant enterococci can be treated with either daptomycin (6 mg/kg after each dialysis session) or oral linezolid (600 mg every 12 hr).

Antibiotic Locks

Antibiotic lock is indicated for patients with CRBSI involving long-term catheters with no signs of exit-site or tunnel infection for whom catheter salvage is the goal.

For CRBSI, antibiotic lock should not be used alone; instead, it should be used in conjunction with systemic antimicrobial therapy, with both regimens administered for 7–14 d.

Dwell times for antibiotic lock solutions should generally not exceed 48 hr before reinstallation of lock solution; preferably, reinstallation should take place every 24 hr for ambulatory patients with femoral catheters. However, for patients who are undergoing hemodialysis, the lock solution can be renewed after every dialysis session.

Catheter removal is recommended for CRBSI due to S. aureus and Candida sp., instead of treatment with antibiotic lock and catheter retention, unless there are unusual extenuating circumstances (e.g., no alternative catheter insertion site).

For patients with multiple positive catheter-drawn blood cultures that grow coagulase-negative staphylococci or gram-negative bacilli and concurrent negative peripheral blood cultures, antibiotic lock therapy can be given without systemic therapy for 10–14 d.

For vancomycin, the concentration should be at least 1000 times higher than the MIC of the microorganism involved.

At this time, there are insufficient data to recommend an ethanol lock for the treatment of CRBSI.

Follow-up Cultures

It is not necessary to confirm negative culture results before guidewire exchange of a catheter for a patient with hemodialysis-related CRBSI if the patient is asymptomatic.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree