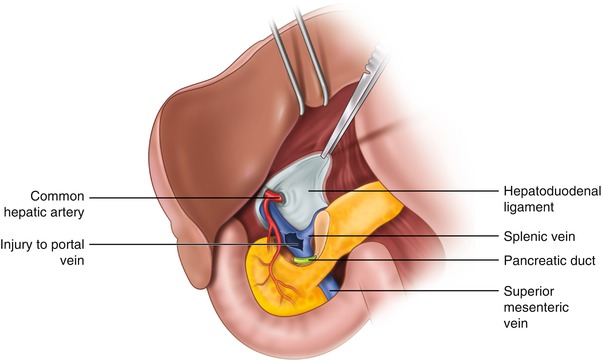

Fig. 8.1

Anatomy of the portal triad

The liver is a particularly unique solid organ, receiving a dual blood supply from the portal vein and the hepatic artery. The liver receives approximately 75 % of its inflow circulation from the portal vein and 25 % from the hepatic artery. The relatively oxygen-rich arterial inflow results in a division of the oxygen supply to the liver between the portal vein and hepatic artery that is roughly even. This unique situation affords the surgeon the option of ligation of an injured vessel, provided that the other vessel remains patent.

Vascular Control and Exposure of Injuries

Hematoma in the hepatoduodenal ligament strongly suggests the presence of injury to the portal vein, the hepatic artery, or both and warrants caution as disruption of the hematoma prior to adequate vascular control or exposure may result in rapid bleeding. On encountering a stable hematoma, it is wise to ensure that vascular clamps, suture, vessel loops, and embolectomy catheters for the purpose of intravascular balloon occlusion are all at the ready. It will be the rare occasion where the anatomy allows for placement of vascular clamps across the hepatoduodenal ligament, both superior (i.e., high on the porta as close to the liver as possible) and inferior (low on the porta just above the duodenum) to the hematoma. If this so-called double Pringle maneuver can be performed, the hematoma may then be opened and the vessel injury may be identified. More often than not, however, the hematoma is too extensive and/or the hepatoduodenal ligament is too short to allow for the placement of two clamps. In this more typical scenario, we recommend proceeding with exposure as facilitated by the Kocher maneuver described below, being prepared to rapidly compress any active bleeding that becomes apparent during mobilization. Occasionally, active bleeding, rather than stable hematoma, will be initially encountered and should be immediately controlled with the application of direct digital pressure. The surgeon’s left hand pinches the site of bleeding with index finger in the foramen of Winslow and thumb anterior (Fig. 8.2). The right hand is then free for dissection of the tissues above and below the pinched off area of bleeding.

Fig. 8.2

(a) The surgeon’s left index finger is positioned in the foramen of Winslow. (b) The site of bleeding is then compressed between the index finger and thumb..

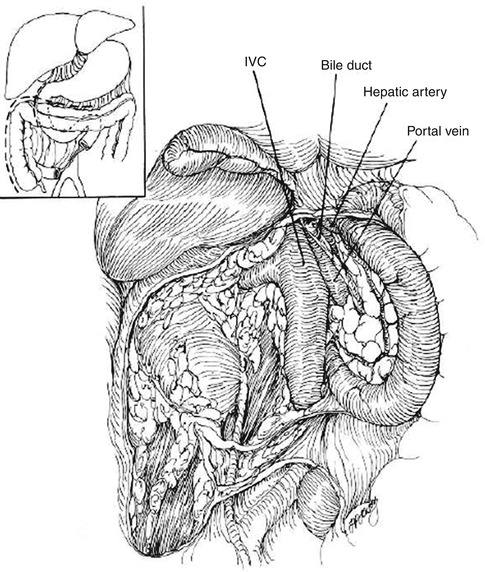

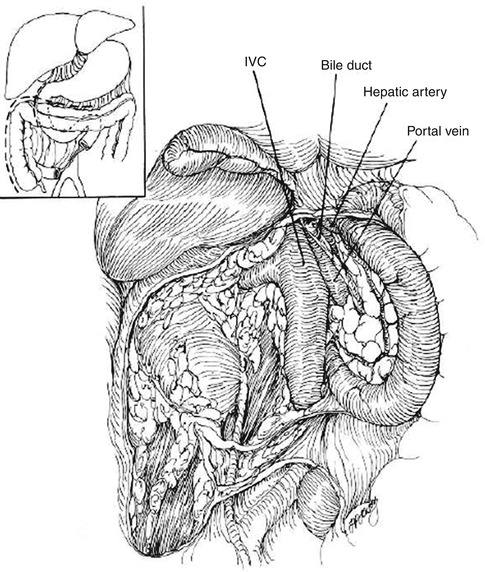

Exposure of the portal vein and hepatic artery is facilitated by anterior reflection of the pancreaticoduodenal complex, known as the Kocher maneuver. Medial mobilization of the right colon is often necessary to gain the required exposure to perform the Kocher maneuver. A complete Kocher maneuver allows for the surgeon or assistant to place gentle traction on the portal triad by holding the duodenum and head of the pancreas between the fingers and thumb of the left hand and pulling inferiorly, facilitating the anterior exposure of the structures in the hepatoduodenal ligament and optimally creating space to place a clamp across the hepatoduodenal ligament for proximal control. The Kocher maneuver also allows for exposure of the lateral aspect of the portal vein (Fig. 8.3). As demonstrated in Fig. 8.3, the common bile duct obscures a portion of the portal vein. Should that portion of the vein need to be fully exposed, it is useful to divide the cystic duct and then reflect the common bile duct medially (if the cystic duct is divided, cholecystectomy should be performed prior to completion of the operation). Figure 8.3 also demonstrates the close proximity of the portal vein to the vena cava. Associated injury to the vena cava and/or adjacent aorta should be anticipated when a portal injury is encountered, and should be addressed once identified, leaving the portal injury temporarily controlled by a clamp or assistant’s fingers for the time being.

Fig. 8.3

Exposure gained following anterior reflection of the pancreaticoduodenal complex (Kocher maneuver) (Reproduced with permission from Ivatury [8])

Retropancreatic injuries of the portal vein or portal vein confluence provide an additional challenge regarding vascular control and exposure, given that the pancreas significantly limits access to the venous structures immediately posterior. Active bleeding necessitates direct anterior pressure on the point of bleeding, while working to expose the injured vessel. As demonstrated in Fig. 8.3, the Kocher maneuver exposes a large portion of the retropancreatic portal vein and allows for vascular control by way of digital compression with fingers behind and thumb on top of the pancreatic body. Division of the pancreatic neck has been advocated as an additional maneuver to expose the retropancreatic venous confluence of the superior mesenteric vein and splenic vein. Should the neck of the pancreas itself be uninjured, however, it is unlikely that the exposure gained by transecting the neck will be worth the time taken to divide the pancreas, and also risks iatrogenic venous injury in a field distorted by retroperitoneal hematoma. Often, however, retropancreatic venous injuries will be associated with a pancreatic neck injury, particularly in the context of a gunshot wound or similar penetrating injury (Fig. 8.4). In such a scenario, it is useful to convert the pancreatic neck injury to a complete transection (followed by distal pancreatectomy), thereby providing both exposure of the retropancreatic venous injury and definitive management of the wound of the pancreas.