Fig. 3.1

(a) Standard lithotomy (b) Low lithotomy, please note that the hip and knee joints are flexed no more than 90° and pressure points are padded (foam)

Catheterization

Catheterization may be needed in several scenarios in the office setting. Non-indwelling or straight catheterization may be used to obtain a sterile specimen for urine culture or, to determine post-void residual (PVR) urine volume. An indwelling catheter is generally placed due to urinary retention. The insertion and maintenance of catheters are important for the elderly population and their caregivers, since roughly 5–10% of all nursing home patients and up to 18% of nursing home patient with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) have Foley catheters [3, 4]. General catheter care involves maintaining a closed drainage system to avoid ascending infection, regularly cleaning of the area that exits the genitalia to prevent encrustation and irritation, and most importantly, removal of the indwelling catheter at the earliest possible time point. Long-term indwelling catheterization is not ideal management due to recurrent infections, urethral erosion, and loss of cyclical bladder function. In patients who are unable to void spontaneously, self-intermittent catheterization is preferred with suprapubic tube drainage (see below) as an alternative option for those patients who are unable to perform self-intermittent catheterization.

Sterile technique including sterile gloves, cleansing of the urethra and surrounding genitalia, and use of a sterile catheter is recommended in the office or hospital setting. Self-intermittent catheterization does not require sterile technique, but hand washing and avoidance of gross contamination is recommended. Liberal use of lubricating jelly or 2% lidocaine jelly will aid the ease in passage of the catheter. At times difficulty is encountered when passing a catheter due to an enlarged prostate, a false passage, a bladder neck contracture, or a urethral stricture. In these scenarios a coude catheter, a guide wire with council tip catheter, or filiforms and followers may be needed (Fig. 3.2).

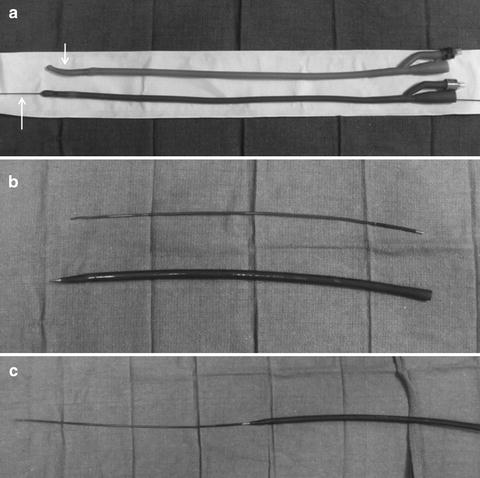

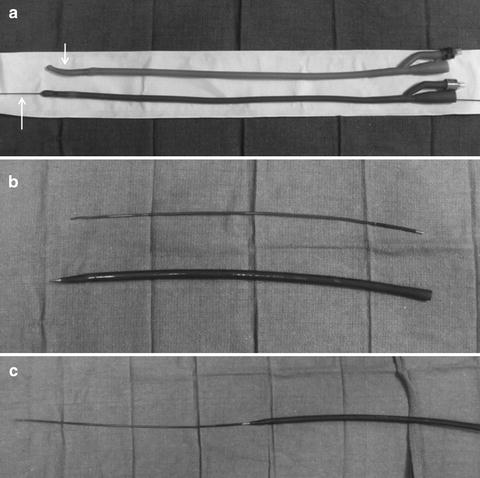

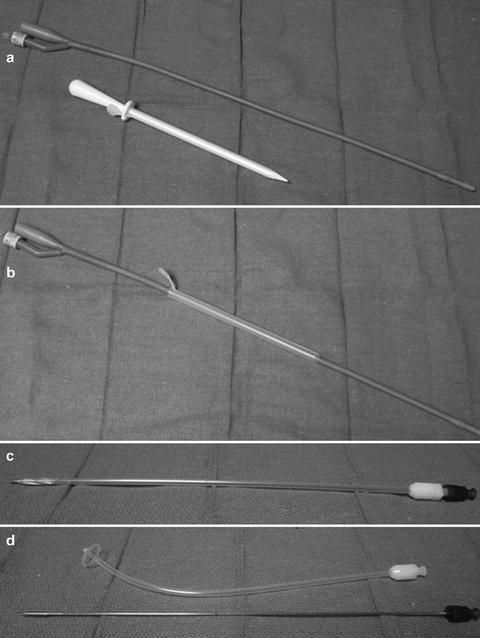

Fig. 3.2

(a) Coude catheter on top, arrow highlights curved tip that allows this catheter to pass through an enlarged prostate, council catheter on bottom, arrow highlights ability of this catheter to be passed over a wire (b) Filiform on top, this instrument in soft and pliable that allows it to traverse a stricture, follower on bottom, this instrument is the dilating element (c) Filiform and follower connected

Urethral Dilation

In the setting of urethral stricture or meatal stenosis urethral dilation may be necessary. A local anesthetic is administered prior to instrumentation. It is critical that the lumen of the stricture be intubated properly to avoid creation of a false passage. The safest method is to use a cystoscope and pass a wire through the narrowed lumen under direct visualization. Over the wire sequential dilators are generally passed until an appropriate luminal diameter is achieved (Fig. 3.3). Urethral sound may be more appropriate in the rare but often over-diagnosed female urethral stricture (Fig. 3.3). Following dilation the physician may place a temporary indwelling catheter to keep the area open, recommended intermittent self-catheterization, or simply have the patient return to the office at a designated time point for interval evaluation.

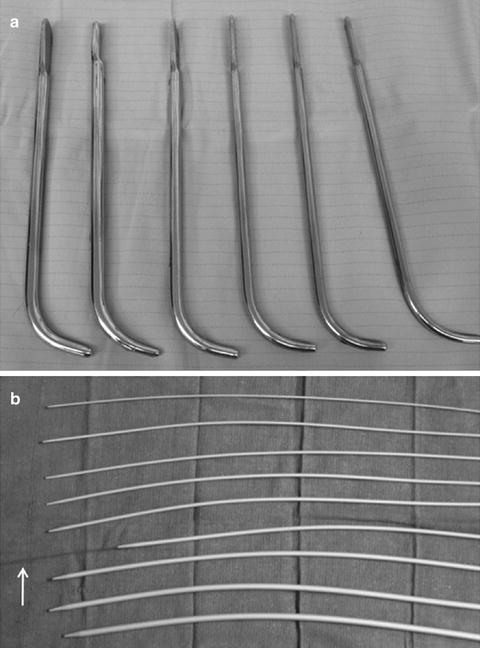

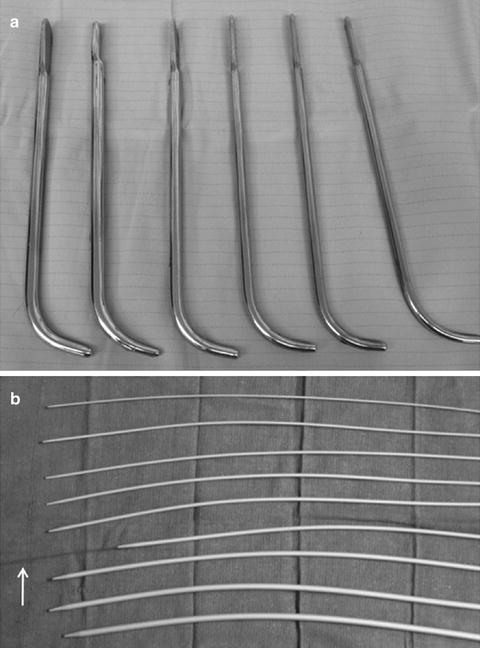

Fig. 3.3

(a) Serial sound dilators (b) Serial urethral dilators, arrow highlights ability of these dilator to be passed over a wire

Cystoscopy

Cystoscopy or cystourethroscopy, is a procedure that allows visualization of the entire bladder and urethra. This can be performed in the office under local anesthesia (2% lidocaine jelly or intravesicle lidocaine). The cystoscope can be flexible or rigid depending on the needs of the patient or the positioning of the patient (Fig. 3.4). Flexible cystoscopy may be performed supine, but rigid cystoscopy requires the lithotomy position. For the comfort of the patient, the smallest diameter cystoscope should be used during rigid cystoscopy (17 French). To aid in visualization a sterile fluid, generally normal saline, is used to distend the urethra and bladder. Biopsies can be obtained by passing forceps through the working channel of the cystoscope. Fulguration of biopsy sites or other areas of the bladder can be performed using Bugbee electrocautery, however glycine, sorbitol, or water must be used as the irrigant. Laser ablation of bladder tumors, lesions, or stones can be performed using various wavelengths of laser energy and specific laser fibers.

Fig. 3.4

(a) Rigid cystoscope (b) Flexible cystoscopy

Reasonable effort should be made to ensure that the patient has sterile urine before proceeding with any urological instrumentation. Current evidence suggests that in uncomplicated situations antibiotics are not required or recommended. In patients with total joint replacements, prophylaxis is recommended in those who have been implanted within the last 2 years and those patients who are high risk (inflammatory arthropathies, immunosuppressed, previous joint infections) [5]. Prophylaxis is not needed in patients with plates, pins, or screws. Currently, the American Heart Association (AHA) does not recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with undergoing urologic procedures for the prevention of infectious endocarditis [6]. Discontinuation of blood thinning agent is not needed in all situations but the physician should be made aware of any blood thinning medications (aspirin, ibuprofen, warfarin, antiplatelet agents). If additional treatment through the cystoscope is anticipated blood thinners should be stopped. Lastly, several authors have noted that bactrim and fluoroquinolones can lead to supratherapeutic INR levels in patients taking coumadin [7]. If these antibiotics are given after cystoscopy, appropriate communication with primary care doctors and geriatric practitioners is needed for INR monitoring in elderly patients taking coumadin.

Side effects of cystoscopy are generally mild. They may include dysuria, hematuria, difficulty urinating, and rarely urinary tract infection. Complications are rare but may include stricture formation, acute urinary retention, bleeding, and clot retention.

Suprapubic Tube Placement

Suprapubic tubes (SPTs) are often employed in urology for patients with neurogenic bladder (who cannot perform intermittent straight catheterization) or when urethral access to the bladder is not feasible (trauma, severe stricture disease). Two recent large studies of 219 and 549 patients each, found that the average age at time of SPT placement was 73 years and 66 years of age, respectively [8, 9]. As such, it is important that elderly patients, their families, and primary caregivers be aware of long-term common complications of SPTs such as urinary tract infections and catheter blockages.

Placement of a suprapubic tube is best performed in the operating room in a controlled setting either through an open incision or percutaneously (with or without the aid of cystoscopy and/or ultrasound). Placement of an SPT in the office should be reserved for emergency situations and should be aided by cystoscopy if feasible as serious complications such as bowel injury, vascular injury, and SPT misplacement can occur.

When performed in the office, the bladder should first be fully distended. Then after local anesthesia is given, a small transverse skin incision should be made about 3–4 cm (or two finger-breaths) above the pubis. Next, a long spinal or “finder” needle should be placed perpendicular to the skin and not too cephalad (away from the bladder) or too caudad (too close to the bladder neck). Urine should be aspirated from the spinal needle to confirm placement if a cystoscopy is not already in the bladder to confirm placement. Next, either a Rousch trocar or cystotomy catheter kit may be inserted in the same direction and aside the spinal needle. For the Rousch trocar, a catheter is placed through the hollow lumen, which is then “peeled” away (Fig. 3.5). For the cystotomy catheter kit, the obturator is removed leaving the catheter in place (Fig. 3.5).

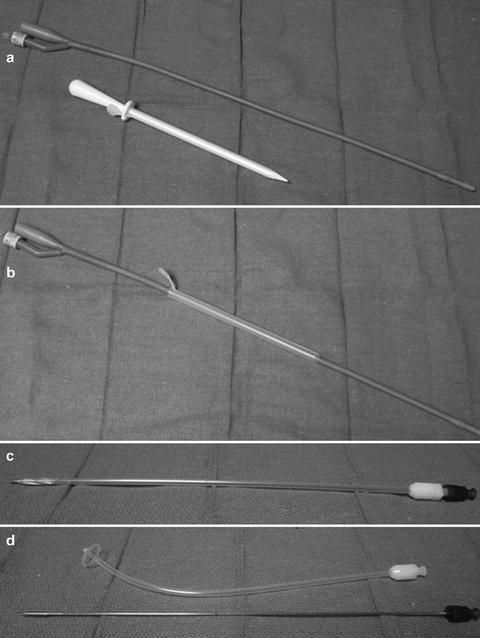

Fig. 3.5

(a, b) Rousch trocar (c, d) cystotomy catheter kit with self retaining head

SPT care is similar to an indwelling urethral catheter (see above). Most urologist exchange SPTs every month in the office, however if encrustation and occlusion are a problem, then exchange may be needed every 2–3 weeks.

Urodynamics

Urodynamics is an important aspect of any urologic practice. Elderly patients may be referred for urodynamics for a variety of reason including bladder outlet obstruction, pelvic organ prolapse, overactive bladder, and urinary incontinence. Of all these reasons, urinary incontinence is perhaps the most bothersome to elderly patients and their caregivers. In fact, incontinence affects as many as 40% of patients in nursing homes and accounts for a significant amount of urodynamic referrals in this population. This sect. will define the urodynamic evaluation as standardized by the International Continence Society (ICS) [10], and will discuss when relevant specific application to the elderly population.

Noninvasive uroflowmetry is the simplest methodology in urodynamics. It should be noted that this method is largely dependent on voided volume (minimum of 150 cc required) and a normal maximum flow rate is derived from nomograms based on age and sex. In men, the lowest acceptable maximum flow rates are 21 mL/s, 12 mL/s, and 9 mL/s in age groups of 14–45 years, 46–65 years, and 66–80 years respectively. In women maximum flow rates are 18 mL/s, 15 mL/s, and 10 mL/s in age groups of 14–45 years, 46–65 years, and 66–80 years respectively [11]. In general, most people would accept >15 mL/s as normal [12]. Figure 3.6 [13] represents the ideal uroflowmetry curve and Table 3.1 defines the terminology [10]. In combination with uroflowmetry, post-void residual urine measurement (PVR) urine completes the noninvasive urodynamic evaluation. PVR measurements are typically assessed by ultrasound exam (or catheterization) within 60 s of voiding. Any further delay in PVR measurements risks a false elevation in the value from continued urine production. The definition of an elevated PVR is not standardized, but a value of greater than 50–100 cc is generally accepted as elevated depending on the clinical situation. Interestingly, PVR is not affected by age of male patients, however in randomly selected men aged 70–79 years about 25% will have a PVR greater than 50 mL [14].

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree