Urolithiasis

Satomi Kawamoto MD

Elliot K. Fishman MD

Case 5-1

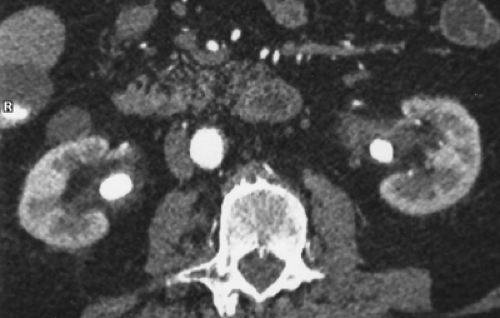

History: 76-year-old male with gross hematuria status post extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for urolithiasis.

Findings: Unenhanced axial image (A) shows large calculi in the renal pelves. Gallstones are also present. Arterial phase axial image (B) again shows calculi in the renal pelves bilaterally. There is mild stranding of the fat surrounding the renal pelves. There is a cyst projecting off the anterior aspect of the right kidney. Excretory phase volume-rendered image (C) shows mild caliectasis bilaterally, left greater than right. The calculi are not visible because their attenuation values are similar to the attenuation of contrast material.

Diagnosis: Bilateral renal pelvis calculi with minimal hydronephrosis

Discussion: Urolithiasis is a common problem; the lifetime risk for stone disease in the urinary tract approaches 20% for males and 5% to 10% for females. The application of spiral (helical) CT for the diagnosis and management of urolithiasis has altered the practice of uroradiology dramatically. Prior to CT, the diagnosis of urolithiasis relied on plain radiography, intravenous urography, and ultrasound.

Almost three-fourths of urinary stones are composed of calcium oxalate, calcium phosphate, or both. Approximately 10% of stones contain no calcium; most of these calculi are composed primarily of uric acid or cystine. Pure uric acid stones are not visible with plain film radiography. However, almost all urinary calculi, including uric acid stones, are visible with unenhanced CT. There are a few exceptions; matrix stones and indinavir-induced stones are not of high attenuation on CT. Matrix stones are often seen as a nonenhancing soft tissue mass within the pelvicaliceal system. Indinavir is a protease inhibitor used in the treatment of HIV infection. Approximately 19% of the drug is excreted in the urine, and poorly soluble indinavir crystals act as nidi for stone formation. These stones are also of soft tissue attenuation.

Case 5-2

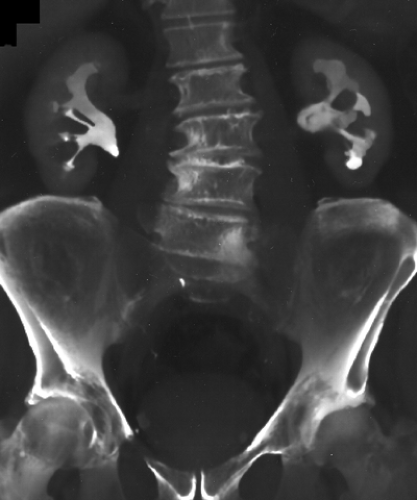

History: 85-year-old male with recurrent gross hematuria.

Findings: Unenhanced volume-rendered image from a CT urogram (A) shows a large calculus in the left renal pelvis. There are smaller calculi in the right renal pelvis, the upper and lower pole calices of the right kidney, and multiple calculi in the bladder. Arterial phase coronal image (B) again shows the large calculus in the dilated left renal pelvis and the smaller calculi in the right renal pelvis. The right kidney contains a cyst and is atrophic compared to the left kidney. There is thickening of both renal pelvic walls, more so on the left (arrow). Excretory phase volume-rendered image (C) shows mild caliectasis bilaterally. The large left renal pelvic calculus is again visualized because the dilated

left renal pelvis is incompletely filled with excreted contrast at the time of the scan, but the right renal calculi are obscured by contrast material in the right renal collecting system. The multiple bladder calculi are also identified.

left renal pelvis is incompletely filled with excreted contrast at the time of the scan, but the right renal calculi are obscured by contrast material in the right renal collecting system. The multiple bladder calculi are also identified.

Diagnosis: Bilateral renal pelvis calculi and bladder calculi with associated pyelitis

Discussion: Chronically indwelling calculi may invoke an inflammatory reaction in the adjacent urothelium, with or without infection, and result in thickening of the urothelium and nearby fat stranding. The findings are indicative of pyelitis (see Case 8-6).

The bladder stones were not visible with plain radiographs and, therefore, were diagnosed as pure uric acid stones. The kidney stones were faintly seen by plain film and thought to be composed of both uric acid and a small amount of calcium. Cystoscopy confirmed the presence of multiple uric acid bladder stones. The patient underwent urinary alkalinization therapy, which significantly decreased stone burden, followed by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. The left renal calculi were eventually found to be composed of 99% uric acid and 1% calcium oxalate monohydrate.

Pure uric acid stones are radiolucent on plain films but, as previously mentioned, easily visible on unenhanced CT images. In comparison, large uric acid stones may incorporate calcium and become radiopaque or serve as a nidus for calcium oxalate stones. Low urinary pH is a significant factor in the formation of uric acid calculi. Uric acid stones form in acidic urine; however, when the urine pH is increased to 6.5 or higher, uric acid has significantly increased solubility. This explains why urinary alkalinization is utilized to treat patients who develop uric acid stones.

Case 5-3

History: 72-year-old male with a history of bladder and kidney stones.

Findings: Unenhanced axial image (A) shows two contiguous calculi in the left renal pelvis. Unenhanced axial image through the pelvis (B) shows a calculus (arrow) in the distal right ureter. Unenhanced coronal reformatted image (C) shows multiple calculi in the renal pelvis and lower pole calyx of the left kidney and the small calculus (arrow) in the distal right ureter. There is no evidence of hydronephrosis or hydroureter.

Diagnosis: Left renal calculi and right distal ureteral calculus, without obstruction

Discussion: Virtually all ureteral calculi originate in the renal medulla or intrarenal collecting system. Stones in the ureter may be nonobstructing, but more commonly they obstruct and result in proximal hydronephrosis.

Calcifications adjacent to the ureter, such as arterial calcifications or phleboliths, may be difficult to differentiate from ureteral calculi, particularly when ureteral calculi are distal and nonobstructing and when the nondilated ureter cannot be identified in the lower abdomen and pelvis. The “soft tissue rim sign” caused by a thickened edematous ureteral wall around a ureteral stone can be seen in 50% to 77% of ureteral calculi but is not present around phleboliths. As a result, identification of the soft tissue rim sign allows for ureteral calculi to be distinguished definitively from phleboliths. Because some ureteral calculi do not cause ureteral wall edema, the absence of the soft tissue rim sign cannot be used to exclude a ureteral stone. A pelvic density without a rim could represent either a phlebolith or a ureteral

calculus. Furthermore, the intraureteral nature of most calculi that demonstrate the soft tissue rim sign is usually otherwise obvious in most patients due to the presence of other signs of urinary tract obstruction, including pelvocaliectasis, ureterectasis, and perinephric and periureteric stranding and fluid.

calculus. Furthermore, the intraureteral nature of most calculi that demonstrate the soft tissue rim sign is usually otherwise obvious in most patients due to the presence of other signs of urinary tract obstruction, including pelvocaliectasis, ureterectasis, and perinephric and periureteric stranding and fluid.

In this patient, the right ureter was slightly dilated and the intraureteral location of the calculus could be identified without the aid of the soft tissue rim sign. Subsequently, the right ureteral calculus was removed ureteroscopically with laser lithotripsy.

Case 5-4

History: 87-year-old male with right hip pain and hematuria. Urinalysis revealed a urinary tract infection.

Findings: Unenhanced axial image from a CT urogram (A) shows a calculus in the right renal pelvis. The right kidney is enlarged, and there is more perinephric stranding on the right than on the left. Arterial phase axial image (B) shows the calculus in the right renal pelvis. Enlargement of the right kidney and perinephric stranding are again seen. Excretory phase volume-rendered image (C) shows minimal caliectasis on the right. The calculus in the right renal pelvis is obscured by excreted contrast material.

Diagnosis: Right renal pelvic calculus and probable acute pyelonephritis

Discussion: Most complications of urolithiasis are a result of obstruction or infection. Renal enlargement and perinephric stranding are signs of obstruction, infection, or both.

Pyelonephritis and its sequelae, such as intrarenal abscess, are common in patients with obstructing calculi, and when the clinical history and CT findings are appropriate, the diagnosis of pyelonephritis can be suggested. Acute pyelonephritis is characterized by fever, flank pain, bacteriuria, and pyuria. CT may show global enlargement of the affected kidney and patchy or wedge-shaped areas of decreased contrast enhancement. These findings are best seen on nephrographic phase images.

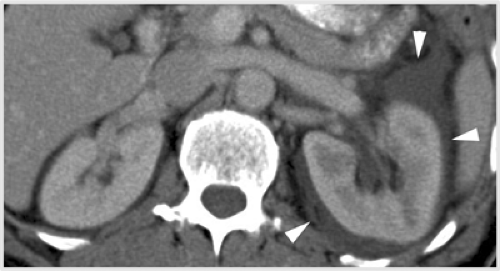

Case 5-5

History: 43-year-old male with severe left flank pain that improved suddenly.

Findings: Nephrographic phase axial images (A, B) show mild hydronephrosis and delayed contrast enhancement of the left kidney. Small nonobstructing calculi are seen in the lower pole calyx of the left kidney on image (B). There is moderate fluid attenuation material around the left kidney (arrowheads). Nephrographic phase axial image of the pelvis (C) shows a calculus in the left distal ureter (arrow). Nephrographic phase curved planar reformatted image (D) shows that there are three calculi in the left distal ureter (arrows) with minimal left hydronephrosis and hydroureter. The fluid attenuation material around the left kidney is again seen.

Diagnosis: Nonobstructing calculi in the lower pole calyx of the left kidney and obstructing left distal ureteral calculi with forniceal rupture

Discussion: Obstructing ureteral calculi are most commonly located at or near the ureterovesical junction. Other common locations include the ureteropelvic junction and where the ureter crosses the iliac vessels. Acute ureteral obstruction causes severe flank pain also known as renal or ureteral colic. Renal colic is due to sudden distention of the proximal collecting system and edema of the kidney, exacerbated by ureteral hyperperistalsis. The combination of severe flank pain accompanied by hematuria is seen in approximately 50% of patients with ureterolithiasis.

For evaluation of renal colic, unenhanced CT or the first scan of a three-phase CT urogram is the study of choice. Contrast-enhanced CT scans are rarely needed. In one study, sensitivity and specificity of unenhanced CT for diagnosis of ureteral calculus in the emergency setting were 97% and 96%, respectively. In acute obstruction caused by a ureteral calculus, CT usually shows the obstructing calculus as well as secondary signs of obstruction, including hydroureter, hydronephrosis, perinephric stranding, and renal enlargement.

Occasionally, the obstructed collecting system can decompress spontaneously by leakage of urine from the renal collecting system, typically from one or more caliceal fornices. The fornix of the calyx is the weakest point of the renal collecting system. Rupture of the caliceal fornix may occur either as a result of a rapid increase in pressure in the renal collecting system due to acute urinary obstruction or during injection of contrast material directly into the renal collecting system during antegrade or retrograde pyelography. In most cases, the resulting extravasated urine tracks into the renal sinus. On delayed phase images of CT urography, the extravasated opacified contrast material may surround the renal pelvis and proximal ureter and extend further in the perinephric space (see Case 9-18). During antegrade and retrograde pyelography, contrast material extravasation occurs as a result of increased pressure and subsequent “backflow” phenomena. In this setting, forniceal rupture results in pyelosinus backflow or pyelosinus extravasation.

As a result of forniceal rupture, the obstructed collecting system becomes decompressed suddenly and, therefore, the patient’s symptoms may improve abruptly. The treating physician may then assume falsely that the obstructing stone has passed. Forniceal rupture due to acute urinary obstruction usually has no clinical significance if the urine is not infected. The fluid will resolve over time, particularly if the urinary tract obstruction is relieved. (Case courtesy of Stuart G. Silverman, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.)

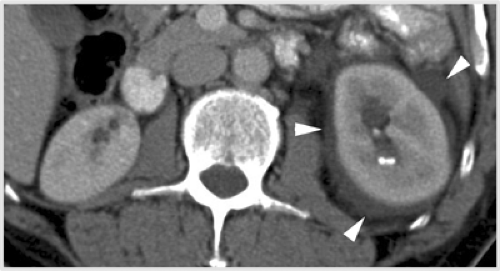

Case 5-6

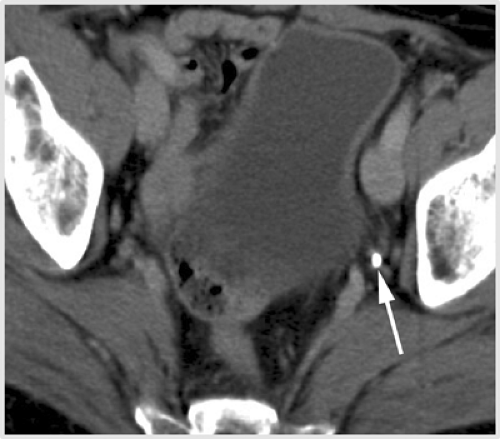

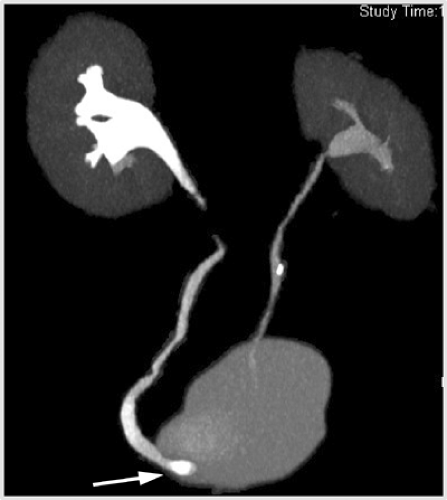

History: 66-year-old male with hematuria.

Findings: Unenhanced axial image of the pelvis from a CT urogram (A) shows a 1-cm calculus at the right ureterovesical junction (arrow). Unenhanced axial image of the pelvis more superiorly (B) shows an additional 4-mm calculus in the right distal ureter, 1.5 cm above the ureterovesical junction (arrow). Excretory phase coronal (C) and MIP (D) images show mild right-sided hydronephrosis and hydroureter. The calculus at the right ureterovesical junction is well-visualized (arrow); however, the smaller calculus in the right distal ureter located more superiorly is obscured by excreted contrast material.

Diagnosis: Obstructing calculi at the distal ureter and right ureterovesical junction