As of 2012, bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer afflicting men and ninth most common cancer in women. Nearly 80% of all bladder cancer diagnoses are non-muscle invasive at presentation, most of whom will develop recurrent disease within 5 years of initial diagnosis. Urinary tumor markers provide a noninvasive method for both screening and surveillance of bladder cancer. This article reviews the current Food and Drug Administration–approved urinary biomarkers for detection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Key points

- •

80% of urothelial carcinoma is non-muscle invasive at diagnosis, and up to 70% will have recurrence within 5 years.

- •

Urine-based tumor markers are an important adjunct in both screening and surveillance of urothelial carcinoma.

- •

Cystoscopy remains the most cost-effective method for identifying bladder cancer recurrence.

- •

Urine cytology is highly specific but lacks sensitivity in detection of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer.

- •

Use of urine tumor markers may best be served when cytology is indeterminate or likely to be inaccurate.

Introduction

It is estimated that there are 585,390 people in the United States living with bladder cancer, and an additional 73,510 cases will be newly diagnosed in 2012. As of 2012, bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer afflicting men and ninth most common cancer in women. Nearly 80% of all bladder cancer diagnoses are non-muscle invasive at presentation. Of patients with non-muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma, 50% to 70% will have at least one recurrence in 5 years, and up to 20% will progress to a more advanced stage during that time. Identifying a test to both screen and facilitate surveillance for bladder cancer is of paramount importance. At present, diagnosis and surveillance of urothelial cancer includes imaging of the upper urinary tracts with computed tomography (CT) urography, urinary cytologic evaluation, and cystoscopy.

A test that is inexpensive, noninvasive, and reproducible and that provides excellent sensitivity and specificity is an ideal candidate for a screening marker. Currently, there are 4 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved bladder cancer tumor markers available for use in the United States. These have been used with varying success. However, the data regarding the consistency and reliability of these markers have been mixed, and the precise role for these new markers other than cytology is yet to be clearly defined. Some of these markers are also more expensive than urine cytology and even cystoscopy. Thus, it is imperative to clearly define a strategy for using these tests in the diagnosis and follow-up of both non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Introduction

It is estimated that there are 585,390 people in the United States living with bladder cancer, and an additional 73,510 cases will be newly diagnosed in 2012. As of 2012, bladder cancer is the fourth most common cancer afflicting men and ninth most common cancer in women. Nearly 80% of all bladder cancer diagnoses are non-muscle invasive at presentation. Of patients with non-muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma, 50% to 70% will have at least one recurrence in 5 years, and up to 20% will progress to a more advanced stage during that time. Identifying a test to both screen and facilitate surveillance for bladder cancer is of paramount importance. At present, diagnosis and surveillance of urothelial cancer includes imaging of the upper urinary tracts with computed tomography (CT) urography, urinary cytologic evaluation, and cystoscopy.

A test that is inexpensive, noninvasive, and reproducible and that provides excellent sensitivity and specificity is an ideal candidate for a screening marker. Currently, there are 4 Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved bladder cancer tumor markers available for use in the United States. These have been used with varying success. However, the data regarding the consistency and reliability of these markers have been mixed, and the precise role for these new markers other than cytology is yet to be clearly defined. Some of these markers are also more expensive than urine cytology and even cystoscopy. Thus, it is imperative to clearly define a strategy for using these tests in the diagnosis and follow-up of both non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) and muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Cytology

Urinary cytology, first described for use in evaluating urothelial cancer in 1945 by Papanicolaou, has been a standard test in the evaluation of bladder cancer. A urine sample is collected, centrifuged, and the sediment resuspended, stained, and evaluated with light microscopy ( Fig. 1 ). The sample is then read by a pathologist who classifies the sample as normal, atypical, or indeterminate; suspicious; or malignant. A malignant sample was previously assigned a grade of 1, 2, or 3. The new standard is to designate a malignant sample as either low-grade or high-grade based on architectural and cytologic criteria to reduce ambiguity and improve interobserver reproducibility.

Several factors affect the utility of urinary cytology. Cancer cells must be sloughed into the urine to be collected. High-grade cancers are more apt to slough into urine than low-grade cancers because of weaker intercellular attachments. The sample is subjectively diagnosed and graded by a cytopathologist, and as such there is both interobserver and intraobserver variability. Inflammatory conditions of the bladder including cystitis and bladder calculi can affect the results. Given these factors, sensitivity of urinary cytology for non-muscle invasive disease is quite variable. Pooled data reveal overall sensitivity for non-muscle invasive disease ranging from 29% to 77%. Overall specificity of cytology ranges from 71% to 100%, with most studies reporting more than 90% specificity for both low-grade and high-grade urothelial cancer.

One of the problems with interpreting urine cytology is that the result is sometimes ambiguous. A result of atypical, atypical suspicious, or suspicious is hard to judge and use in management decisions. Individuals who have undergone recent instrumentation or have evidence of inflammation or stone disease may demonstrate an atypical cytology. However, if these individuals also have a history of urothelial carcinoma, the interpretation of the urine cytology reading is difficult. This could lead to unnecessary work up and related morbidity and cost. The use of some of the alternative urine-based markers could potentially serve to improve the accuracy of urine cytology or arbitrate indeterminate results.

UroVysion (fluorescence in-situ hybridization)

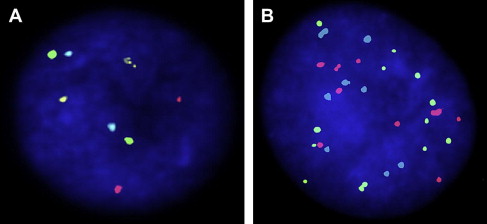

The UroVysion (Abbott Molecular Inc, Des Plaines, IL, USA) test uses fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) to detect increased copy numbers, or aneuploidy, of chromosomes 3, 7, and 17, as well as homozygous deletions of loci at chromosome 9p21. A positive test is determined by presence of either (1) 5 or more cells with 2 or more chromosomal gains (chromosomes 3, 7, 17), or (2) 12 or more cells with gain of a single chromosome, or (3) 12 or more cells with homozygous detection of 9p21 locus ( Fig. 2 ). False-positive results can occur when a barbotage sample is used because of probe uptake in multinucleated umbrella cells, which are dislodged and can be falsely elevated in barbotage specimens. These cells typically constitute only 2% of the cells in a urine sample, but up to 11% in a barbotage sample. Other explanations for a false-positive FISH include the presence of an inclusion body such as a polyoma virus and seminal vesicle cells. False-negative FISH is seen in the presence of degenerated cells, hyphae, excess lubricant, squamous cells, and autofluorescent bacteria. Positivity with aneuploidy of chromosomes 7 and 17 is more commonly associated with the presence of tumor compared with positivity with aneuploidy of chromosome 3 or loss of 9p21. The loss of 9p21 is also more commonly associated with the presence of low-grade, nonmuscle invasive tumors. Additionally, the result of an UroVysion FISH test may be positive in the absence of a positive cystoscopic or cytologic evaluation; this occurs in 35% to 63% of patients up to 6 to 20 months before development of a macroscopically visible urothelial malignancy and has been deemed an “anticipatory positive” FISH test.

UroVysion FISH is more sensitive for high-grade and invasive urothelial malignancies, with reported sensitivity ranging between 83% and 100%. It is also fairly sensitive at detecting non-muscle invasive tumors, with sensitivity ranging from 64% to 76%. UroVysion FISH is nearly as specific as urinary cytology with reported specificity ranging from 89% to 96%. FISH has also been shown to have utility in surveillance for urothelial carcinoma recurrence after intravesical bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) therapy. Both cystoscopy and cytology are often inconclusive following BCG therapy because of the confounding effect of BCG-induced inflammation. Patients with a positive FISH following BCG therapy have demonstrated nearly 10-fold higher likelihood of muscle invasive disease as compared with patients with a negative FISH after BCG. A positive FISH test after intravesical BCG therapy is also associated with a higher likelihood of nonresponse to BCG and recurrent tumor ( Table 1 ).

| No. Patients | Tumor Recurrence Post-BCG | % MIBC (≥T2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%) | Positive FISH with Recurrent Tumors | Negative FISH with Recurrent Tumors | |||

| Kipp et al, 2005 | 37 | 67 | 100% | 52% | 58 |

| Whitson et al, 2009 | 42 | 43 | 89% | 26% | 5 |

| Mengual et al, 2007 | 65 | 36 | 52% | 25% | 10 |

| Savic et al, 2009 | 68 | 38 | 76% | 26% | |

| Kamat et al, 2012 | 126 | 31 | 50% | 18% | 28 |

More recently, UroVysion FISH has also been used to adjudicate the results of urine cytology, which are read as “atypical.” Given that FISH examines the chromosomal abnormalities in a cell that are less susceptible to conditions that may affect cell morphology such as inflammation or BCG therapy, it may serve as an attractive second level test in patients with hard to interpret urine cytology results. Schlomer and colleagues examined the utility of reflex FISH testing in 120 patients with atypical urine cytology. They found that in patients with a positive cystoscopy, additional FISH testing was of little value. In those with an equivocal cystoscopy or with a negative cystoscopy, the negative predictive value (NPV) of FISH was 100%. They concluded that reflex FISH testing could eliminate the need for further workup and biopsy in patients with an atypical cytology, negative FISH and equivocal or negative cystoscopy. They found no patients with an atypical cytology and a false-positive FISH test.

FISH testing has also been able to detect patients with bladder cancer of nonurothelial histology as well as cancers in adjacent organs such as colon and prostate. Sensitivity for detection of adenocarcinoma is as high as 79%. FISH testing of other body fluids such as pleural effusion fluid can help detect tumor cells.

Nuclear matrix protein 22

Nuclear matrix proteins (NMPs) are structural components of the cell nucleus, and also function in regulation of gene expression and DNA replication. NMP22 is a protein specific to mitosis and is involved in the distribution of chromatids to daughter cells. The concentration of NMP22 has been shown to be up to 25 times greater in bladder cancer cell lines than normal urothelium. Inflammatory conditions including cystitis, pyuria, urolithiasis, and hematuria can result in elevated urinary NMP22 levels. NMP22 is available as a point-of-care assay called BladderChek (Stellar Pharmaceutics, Inc, London, Ontario) ( Fig. 3 ) that provides immediate results at half the cost of urine cytology.

Several studies have evaluated patients with NMP22 and have examined cohorts that were further subdivided as superficial and invasive disease. Sensitivity of NMP22 in non-muscle invasive disease ranged from 54% to 63% and 70% to 100% sensitive for muscle invasive disease. Overall specificity of NMP22 in urothelial carcinoma ranged from 55% to 90%. Grossman, and colleagues evaluated 1331 patients at high risk for urothelial carcinoma with NMP22, cytology, and cystoscopy. Seventy-nine cancers were biopsy proven, 62 of which were non-muscle invasive disease. The sensitivity of NMP22 in this group was 50% compared with 16% for cytology.

A Canadian group prospectively evaluated patients with high-risk superficial disease (tumors that are high-grade, carcinoma in-situ or T1, >3 cm, and recurrent disease at initial 3-month cystoscopy) with NMP22. Fifteen patients out of 94 tested had a positive NMP22 test result and 9 of the 15 patients developed a subsequent recurrence (60%), which is compared with 30 patients with recurrence and a negative NMP22 test (37%). The group concluded that NMP22 may be helpful to risk-stratify patients on surveillance, but NMP22 results in this population did not predict progression-free survival or overall survival. The combination of cystoscopy and NMP22 has been shown to have a higher sensitivity than the combination of cytology and cystoscopy (99% vs 94%), which along with the immediate availability of results, makes it more attractive to use NMP22 BladderChek as an adjunct to cystoscopy. However, the higher false-positive rate of NMP22 has hampered the wide adoption of this approach.

NMP22 along with other markers has also been used in several studies testing the concept of screening for bladder cancer. The ease of use and rapid availability of the results from the NMP22 BladderChek test render it attractive in this context. However, results from the studies suggest that the BladderChek test does not significantly aid in identification of patients with bladder cancer. The false negative rate of NMP22 was found to be too high. NMP22 can also yield false-positive tests in the presence of inflammation and hematuria, which raises concerns regarding its use in the setting of screening.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree