Urethral obstruction after surgery to treat stress urinary incontinence is reported to occur in 5% to 20% of patients. Surgeons who perform these procedures should be adept at recognizing the signs of iatrogenic obstruction and be comfortable with performing a procedure to unobstruct the patient or with referring the patient to someone with more experience in this area. In most cases, timely recognition and treatment lead to significant symptom relief.

Urethral obstruction after surgery to treat stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is reported to occur in 5% to 20% of patients. Studies report that the incidence of surgery for treating SUI has increased dramatically over the past decade. If only patients requiring an inpatient admission are taken into account, the rate increases by 45%. As most of these procedures are done in the outpatient setting, this figure vastly underestimates the true increase. With this increase in the number of procedures performed, there likely also has been an increase in the number of patients with iatrogenic urethral obstruction. Surgeons who perform these procedures should be adept at recognizing the signs of iatrogenic obstruction and be comfortable with performing a procedure to unobstruct the patient or with referring the patient to someone with more experience in this area. In most cases, timely recognition and treatment lead to significant symptom relief.

Mechanisms of obstruction

Although an aggressive cystocele repair or other type of pelvic surgery occasionally can lead to iatrogenic urethral obstruction, most cases result from procedures for stress urinary incontinence. Retropubic bladder neck suspensions (BNS), transvaginal suspensions, and traditional bladder neck or midurethral slings can obstruct the urethra.

With a retropubic BNS, the sutures elevating the bladder neck may be too tight or too close to the urethra, or exuberant scarification may have occurred between the pubis and urethra. This situation can lead to kinking and compression of the urethra, resulting in obstruction. A similar mechanism may occur with a transvaginal BNS. With a sling, there is typically less scarring anterior to the urethra. Not much dissection usually is done anterior to the urethra or between the urethra and the pubis. Most scarring occurs in a more lateral area where the sling perforates the endopelvic fascia. In most obstructing slings, the cause of the obstruction likely is unrelated to anterior or lateral scarification and more likely is related to ventral compression of the urethra by the sling. This concept is supported by the fact that simple division of the sling beneath the urethra, which sometimes is accompanied by stripping of the edges of the sling from the ventral surface of the urethra, usually resolves the problem. Although these problems can be related to tying a sling too tight, other unclear patient characteristics or exuberant scarring may lead to obstruction, even in cases in which the sling appeared to be loosely tied. Even the most experienced surgeon runs into this problem on occasion.

Patient evaluation

Patients with iatrogenic urethral obstruction may present with obstructive or irritative symptoms. Patients who are in retention or complain of markedly diminished force of urinary stream after surgery are easy to identify. Some patients may have more subtle symptoms. Bending forward to void or having to change positions to effectively void usually indicates an element of obstruction. Recurrent urinary tract infections that are associated with an elevated postvoid residual may suggest obstruction. Irritative symptoms, such as new-onset or worsened urgency, urge incontinence, or urinary frequency, may result from the bladder’s response to obstruction. Although conservative measures (ie, anticholinergic medication or pelvic floor exercises) may help relieve these symptoms, the possibility of obstruction must be entertained.

The most crucial part of the history is the temporal relationship between surgery and the onset of these symptoms. When a patient complains of new-onset obstructive or irritative symptoms after anti-incontinence surgery, iatrogenic obstruction should be suspected.

On physical examination, hypersuspension of the urethra may be identified. The anterior vaginal wall in the area of the bladder neck may be difficult to visualize and may be fixed to the undersurface of the pubis. During a Q-tip test, the Q-tip may have to be guided over a bump to pass it into the bladder, and a resulting negative (downward) deflection of the tip frequently is noted. On cystoscopy, a ridge at the point of obstruction may be visualized. The previous findings less commonly are noted in obstruction caused by midurethral synthetic slings. Although these signs may help solidify the diagnosis of obstruction, their absence does not rule it out.

Urodynamics can be performed and often demonstrates outflow obstruction. Because many women void with low detrusor pressures, the obstructed state may not cause a significantly elevated detrusor pressure and may not give a classic picture of obstruction. Previous studies have found that outcomes after urethrolysis do not depend on urodynamic findings.

Ultimately, patients with a clear temporal relationship between onset of symptoms and anti-incontinence surgery should be considered for urethrolysis. A corroborating physical examination or urodynamic evidence can further solidify the decision.

Patient evaluation

Patients with iatrogenic urethral obstruction may present with obstructive or irritative symptoms. Patients who are in retention or complain of markedly diminished force of urinary stream after surgery are easy to identify. Some patients may have more subtle symptoms. Bending forward to void or having to change positions to effectively void usually indicates an element of obstruction. Recurrent urinary tract infections that are associated with an elevated postvoid residual may suggest obstruction. Irritative symptoms, such as new-onset or worsened urgency, urge incontinence, or urinary frequency, may result from the bladder’s response to obstruction. Although conservative measures (ie, anticholinergic medication or pelvic floor exercises) may help relieve these symptoms, the possibility of obstruction must be entertained.

The most crucial part of the history is the temporal relationship between surgery and the onset of these symptoms. When a patient complains of new-onset obstructive or irritative symptoms after anti-incontinence surgery, iatrogenic obstruction should be suspected.

On physical examination, hypersuspension of the urethra may be identified. The anterior vaginal wall in the area of the bladder neck may be difficult to visualize and may be fixed to the undersurface of the pubis. During a Q-tip test, the Q-tip may have to be guided over a bump to pass it into the bladder, and a resulting negative (downward) deflection of the tip frequently is noted. On cystoscopy, a ridge at the point of obstruction may be visualized. The previous findings less commonly are noted in obstruction caused by midurethral synthetic slings. Although these signs may help solidify the diagnosis of obstruction, their absence does not rule it out.

Urodynamics can be performed and often demonstrates outflow obstruction. Because many women void with low detrusor pressures, the obstructed state may not cause a significantly elevated detrusor pressure and may not give a classic picture of obstruction. Previous studies have found that outcomes after urethrolysis do not depend on urodynamic findings.

Ultimately, patients with a clear temporal relationship between onset of symptoms and anti-incontinence surgery should be considered for urethrolysis. A corroborating physical examination or urodynamic evidence can further solidify the decision.

Choice of procedures

There are a number of ways to free up the obstructed urethra. A urethrolysis can be performed transvaginally or from an open retropubic approach. With a transvaginal approach, one can start ventral to the urethra and dissect laterally and anteriorly through the endopelvic fascia and between the anterior surface of the urethra and the pubis. Alternatively, one can incise above the urethra and directly separate it from its anterior attachments. A combination of these transvaginal techniques may be required to fully free the urethra. The less invasive technique of sling incision has been described. Wrapping a Martius flap around the urethra at the time of urethrolysis is another option, and although most surgeons reserve this approach for patients with recurrent obstruction, some surgeons have advocated its use in primary procedures.

The approach used depends on the type of incontinence surgery that led to the obstruction, whether urethrolysis has been attempted in the past, and whether the surgeon is comfortable with the various approaches.

For patients who previously underwent a sling procedure, regardless of whether the sling was placed at the bladder neck or midurethral, a sling incision may be attempted first. If that approach fails to provide adequate release during surgery or if the patient has recurrent problems, a traditional transvaginal urethrolysis should be performed. Cutting the sling sutures from above and not addressing the ventral obstruction caused by the sling itself are unlikely to be helpful. Within a few weeks, the ends of the sling scar into the retropubic space and cutting the sutures above does not release the sling. After a transvaginal BNS, a traditional transvaginal approach is usually the procedure of choice. Some investigators have advocated a suprameatal, transvaginal approach, suggesting that because the endopelvic fascia remains intact, there is less hypermobility and incontinence after urethrolysis.

For patients with recurrent symptoms after a transvaginal approach, a repeat transvaginal approach with a Martius fat graft is reasonable. Extension to include a suprameatal approach may be necessary. After a failed transvaginal approach, a retropubic approach also may be a good choice and allow better access to retropubic sutures and scar tissue.

If the inciting surgery was a retropubic BNS, a transvaginal or retropubic approach may be attempted. It may be hard to cut all of the sutures or adhesions transvaginally. Although a retropubic approach entails an abdominal incision, it allows full and unimpeded access to all retropubic sutures and scar tissue.

Urethrolysis technique

Sling Incision

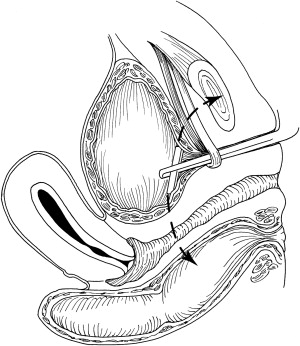

The patient is placed in a steep Trendelenburg position and positioned in a standard fashion for vaginal surgery. Because of hypersuspension, the bladder-neck area can be difficult to visualize in patients who had a traditional bladder neck sling. A 19-Fr cystoscope sheath or Lowsley retractor is placed within the urethra and gently torqued upward, placing tension on the sling and allowing for easy identification of the constricting band (sling) ( Fig. 1 ). A vertical incision is made through the vaginal wall over the sling. With careful blunt and sharp dissection, the sling is identified, and the cystoscopy sheath is changed for a Foley catheter.