Risk factors

Tobacco smoking

Increased lifetime risk with increased consumption and intensity of smoking

Analgesic abuse

Long-term use of analgesics, especially phenacetin

Balkan nephropathy

Papillary necrosis

Occupation carcinogen exposure

α/β-Naphthylamine, benzidine, aniline dye, petrochemicals, plastic materials, coal,

asphalt, tar, and thorium-containing contrast media (Thorotrast)

Previous urinary bladder carcinoma

>2/3 of patients have prior, concurrent, or subsequent bladder carcinomas

Chronic irritation

Urinary stones

Infection

Cyclophosphamide therapy

Hereditary non-polyposis colon carcinoma

Histologic Classification of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma

Multiple series confirm that the predominant type of carcinoma arising in the mucosa of the upper urinary tract is urothelial carcinoma, which is diagnosed in >90 % of cases [1–6]. A histologic classification of the different types of carcinomas of the urothelial tract is shown in Table 3.2. Upper tract carcinomas are noted for showing a wide spectrum of variant morphologies. Recent reviews identify that aberrant squamous and glandular differentiation and the micropapillary variant are most frequent at these sites [14]. Additional morphologies include lymphoepithelioma-like, sarcomatoid, clear cell, rhabdoid, small cell neuroendocrine, signet-ring, small and large nested, and plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas [15]. In fact, these variants may be more prevalent in the upper urothelial tract than in the bladder [2].

Table 3.2

Classification of neoplasms of the ureter and renal pelvisa

Urothelial neoplasms |

|---|

Benign |

Urothelial papilloma |

Inverted papilloma |

Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential |

Malignant |

Papillary |

Typical, noninvasive |

Typical, with invasion |

Variant (with squamous or glandular differentiation) |

Micropapillary |

Non-papillary (flat) |

Carcinoma in situ |

Invasive carcinoma, including the variants below: |

Variants containing or exhibiting deceptively benign features |

Nested pattern (resembling von Brunn’s nests) |

Large nested pattern |

Small nested pattern |

Small tubular pattern |

Microcystic pattern |

Inverted pattern |

Squamous differentiation |

Glandular differentiation |

Undifferentiated carcinoma |

Small cell carcinoma/high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma |

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma |

Micropapillary |

Giant Cell Carcinoma |

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma |

Sarcomatoid foci (“sarcomatoid carcinoma”) |

Urothelial carcinoma with unusual cytoplasmic features |

Clear cell |

Plasmacytoid |

Rhabdoid |

Urothelial carcinoma with syncytiotrophoblasts |

With unusual stromal reactions |

Pseudosarcomatous stroma |

Stromal osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia |

Osteoclast-type giant cells |

With prominent lymphoid infiltrate |

Myxoid stroma/chordoid differentiation |

Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

Typical |

Variant histology, including verrucous carcinoma and basaloid squamous cell carcinoma |

Adenocarcinoma |

Histologic variants |

Typical (Enteric type) |

Mucinous (including colloid) |

Signet-ring cell |

Clear cell |

Hepatoid |

Mixed Adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) |

Undifferentiated Carcinoma (pure/no synchronous or history of urothelial carcinoma) |

Small cell carcinoma (pure/no synchronous or history of urothelial carcinoma) |

Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (pure/no synchronous or history of urothelial carcinoma) |

Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma (pure/no synchronous or history of urothelial carcinoma) |

Giant cell carcinoma (pure/no synchronous or history of urothelial carcinoma) |

Metastatic Carcinoma |

The morphologic variation present in these tumors can present diagnostic challenges: while a conventional papillary or flat urothelial carcinoma is quite familiar to the surgical pathologist, the remarkable variety of variants is not, with some studies suggesting that variant differentiation may be under-recognized by surgical pathologists [16, 17]. Additionally, cases of urothelial carcinoma with extensive variant differentiation underscore one of the limitations of interpretation of small biopsies and the importance of appropriate sampling of resection specimens; a carcinoma showing an extensive pattern of squamous differentiation may only be recognized as a urothelial carcinoma with squamous differentiation if an unequivocal urothelial carcinoma component (whether in situ, invasive, or papillary in architecture) is identified, at least focally [15].

Gross Features

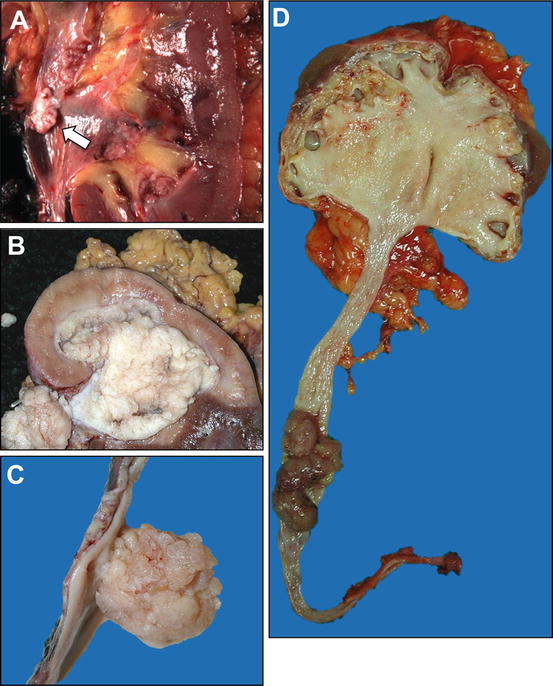

Grossly, urothelial carcinomas of the upper tract may appear as papillary, polypoid, ulcerative, or infiltrative masses, with thickening of the renal pelvic or ureteral wall (Fig. 3.1a–d). Tumors with papillary or polypoid features are more likely noninvasive; such cases may grow significantly and completely fill the lumen of the ureter and the pelvicalyceal system. An expansion into the lumen of the distal ureter, the most common tumor location, can cause an obstruction, resulting in hydronephrosis [13]. Carcinomas that invade the renal parenchyma may grossly mimic a high-grade primary renal carcinoma, from which it may be difficult to distinguish, especially in core biopsies or limited samples [18–21].

Fig. 3.1

Gross appearance of urothelial neoplasms of upper urinary tract. (a) A small noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis (arrow). (b) Urothelial carcinoma extensively involving the renal pelvis, minor calyces, and proximal ureter. (c) Urothelial carcinoma of the ureter showing papillary and polypoid appearance. (d) Urothelial carcinoma of the ureter causing complete obstruction, resulting in hydronephrosis

Intraoperative assessment by frozen section may complement the imaging findings to determine whether a tumor originates from the urothelial lining or the renal parenchyma, a distinction which may direct the surgical or chemotherapeutic management. Invasive carcinomas of urothelial origin typically require a radical nephroureterectomy, whereas primary renal cortical tumors may be managed by radical or “nephron-sparing” partial nephrectomy. Another important aspect of the gross evaluation of the tumor is to assess for multifocality, because the pathologic stage may vary for different tumors [13].

Urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis may present either as large papillary/polypoid tumors expanding the pelvicalyceal system or as broadly infiltrative cancers of the renal parenchyma. These tumors are often centered on the renal pelvis and medulla, but in some instances this may not be apparent grossly. Careful dissection is necessary to preserve the relationship of infiltrative tumors within the renal medulla to the pelvicalyceal mucosa and the renal parenchyma. Thus, multiple histologic sections are often necessary to demonstrate the anatomic relationships and clarify the differential diagnosis and the pathologic stage. Infiltrative carcinomas, particularly if arising in or centered on the minor calyces, may also grossly mimic renal cortical neoplasms. Ulcerative or infiltrative lesions may cause mucosal defect or thickening of the ureteral or the pelvic wall, which sometimes may be more difficult to appreciate grossly [13], underscoring the importance of a careful gross evaluation and sectioning.

Histopathology and Differential Diagnoses

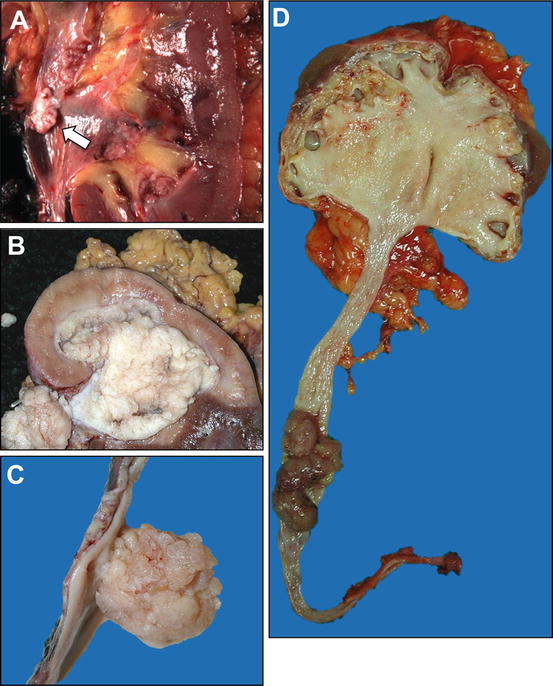

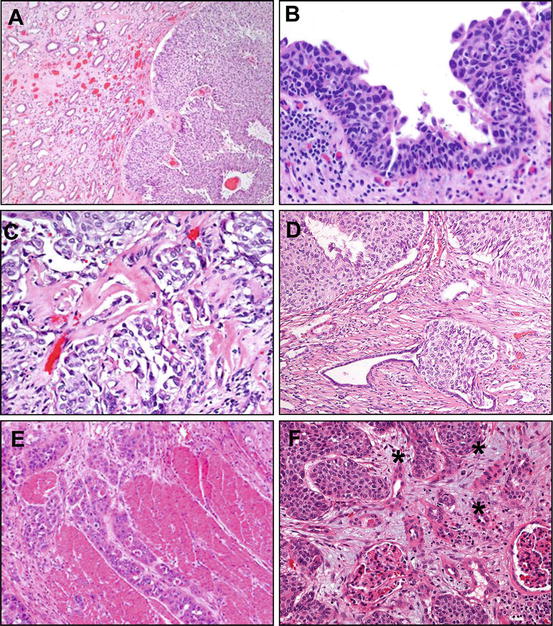

The histopathology of upper urinary tract tumors is analogous to the histopathology of the urothelial neoplasia of the urinary bladder, as illustrated in Table 3.2, and demonstrates the same histopathologic diversity seen in bladder tumors [2, 4, 6, 10, 13, 22]. The basic histopathology of upper urinary tract tumors includes papillary noninvasive tumors (papilloma, papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential “PUNLMP,” low-grade papillary carcinoma, or high-grade papillary carcinoma), carcinoma in situ, and invasive carcinoma. PUNLMP appears to be extremely rare in the upper urinary tract, and low-grade carcinoma is also less common compared to lesions in the bladder. High-grade carcinomas are the most common upper urinary tract tumors, and they are often invasive at presentation. About 70 % of all tumors in the renal pelvis are high-grade urothelial carcinomas [2, 6]. Although the broad histologic spectrum seen in the bladder can also be seen in the upper urinary tract, several divergent carcinoma morphologies occur more frequently in the pelvicalyceal system. These patterns include micropapillary, lymphoepithelioma-like, sarcomatoid, squamous or glandular differentiation, rhabdoid, signet-ring, small cell, or plasmacytoid, as well as a variety of lesions with giant cells, even with trophoblastic differentiation [2]. Some of these are illustrated in Fig. 3.2a, b. Table 3.3 outlines the five most common forms of variant differentiation as recently reported in a large multi-institutional cohort [14], including pathologic lesions in the differential diagnosis and clinicopathological significance.

Fig. 3.2

(a) Urothelial carcinomas of upper tract demonstrate divergent morphologies. A. Plasmacytoid variant of urothelial carcinoma is characterized by single-cell discohesive appearance. B. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas frequently demonstrate areas of signet ring cell morphology. C. Squamous differentiation is often seen in urothelial carcinoma of the upper tract. A morphologic hallmark of squamous differentiation is keratinization and formation of keratin pearls (adjacent to asterisks) in this low power micrograph. D. Urothelial carcinoma with prominent squamous differentiation. In a case with extensive squamous (or other variant) differentiation, urothelial vs. primary squamous carcinoma requires careful sampling and inspection for a conventional urothelial component. This distinction may guide therapy selection. (b) Urothelial carcinomas of upper tract demonstrate divergent morphologies. A. Sarcomatoid differentiation may also occur with urothelial carcinomas of the upper tract, characterized by markedly atypical, spindled cell growth. B. Higher power view of a sarcomatoid urothelial carcinoma shows pleomorphic spindled cells with atypical mitoses, reminiscent of a pleomorphic sarcoma. C. Small cell carcinoma can also be seen in the upper tract. Urothelial carcinoma in situ (asterisk) is shown, a variant of high-grade neuroendocrine (small cell) differentiation. A primary small cell carcinoma or a metastasis from another site, such as lung, needs to be ruled out clinically in these cases. D. Neuroendocrine differentiation may be confirmed immunohistochemically by appropriate immunostains, such as synaptophysin (illustrated), chromogranin, or CD56

Table 3.3

Most frequent patterns of variant differentiation in upper tract urothelial carcinoma

Variant | Differential diagnosis | Significance |

|---|---|---|

Squamous | Primary squamous cell carcinoma; keratinizing and non-keratinizing squamous metaplasia; condyloma acuminatum with extension into the bladder | Poor prognosis overall; possible inferior response to chemoradiation |

Glandular | Primary adenocarcinoma, including clear cell and enteric variants; intestinal metaplasia; villous adenoma; urachal adenocarcinoma; metastatic adenocarcinomas | Poor prognosis overall; limited data on treatment implications |

Sarcomatoid | Primary sarcomas of the bladder, including leiomyosarcoma, undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors, and rhabdomyosarcoma; urothelial carcinomas with pseudosarcomatous stromal changes; pseudosarcomatous myofibroblastic proliferations/inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors | Remarkably poor prognosis, including median survival of 1 year; consideration of sarcoma-directed chemotherapy |

Micropapillary | Adenocarcinomas with micropapillary morphology of other sites, including breast and papillary serous adenocarcinomas of the gynecologic tract | High stage disease at presentation, including vascular invasion and nodal metastasis; poor prognostic histology; may be associated with Her2/neu molecular alterations |

Small Cell | Primary small cell carcinoma (not arising from a urothelial carcinoma), metastatic small cell carcinoma from lung or by direct extension from prostate; small round blue cell tumors (rhabdomyosarcoma); lymphoma | High stage disease with poor prognosis, wide metastatic dissemination, and possible paraneoplastic syndromes; chemotherapy used for pulmonary counterparts often offered |

In one large study, these variant morphologic features were present in 40 % of renal pelvis tumors [2]. To add to the morphologic diversity of these lesions, recent reports have identified three additional variants of urothelial carcinoma, urothelial carcinoma with myxoid stroma (so-called “chordoid” differentiation), which may simulate mucinous adenocarcinoma, myxoid sarcomas, or myoepithelial neoplasms [23], large nested urothelial carcinoma, which is low-grade appearing and a mimic of benign processes [24], and large cell undifferentiated carcinoma, which engenders a wide differential, including metastatic carcinomas of other sites, sarcomas, and even melanoma [25]. In most studies, variant differentiation has been associated with advanced stage and poor outcomes [15]; recent studies suggest that the association with poor outcome is related to advanced stage at presentation or at surgery rather than as an independent prognostic or predictive factor [14].

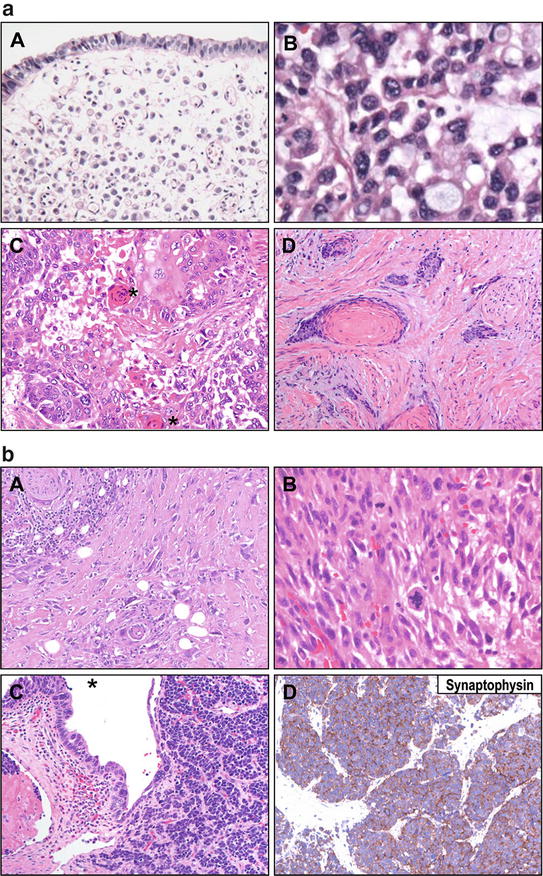

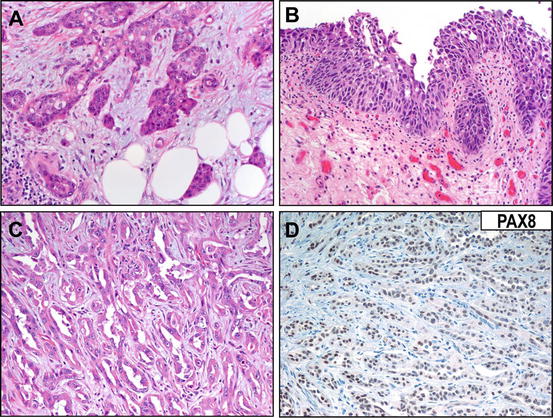

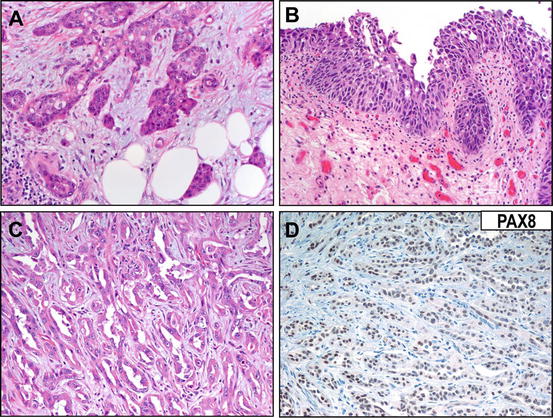

The microscopic diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract may be either straightforward, or it may mimic collecting duct carcinoma, high-grade undifferentiated renal cell carcinoma (RCC), or a metastasis. Urothelial carcinomas and carcinomas of the collecting ducts of Bellini (collecting duct carcinomas) or high-grade undifferentiated RCC may demonstrate similar features, such as an infiltrative pattern and a desmoplastic response in the renal medullary region [13]. A predominantly nested, solid, or trabecular invasive architecture with a variable squamous or glandular component favors urothelial carcinoma. Additional features in favor of urothelial carcinoma include history of urothelial cancer, coexisting papillary urothelial neoplasia involving the pelvicalyceal system, or presence of carcinoma in situ. In contrast, collecting duct carcinoma is essentially a high-grade adenocarcinoma with recognizable glandular architecture. Dysplastic features may often be present in the adjacent renal tubules, and urothelial carcinoma in situ should be absent. Figure 3.3 illustrates key points in the differential diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma versus collecting duct carcinoma.

Fig. 3.3

Differentiating urothelial carcinoma from collecting duct carcinoma can be challenging. (a) An invasive upper tract urothelial carcinoma showing small, infiltrative nests simulating the malignant glandular morphology of collecting duct carcinoma. (b) Identification of an in situ urothelial carcinoma may be helpful in establishing urothelial origin for the neoplasm. (c) A representative field showing collecting duct carcinoma morphology, composed of invading cords and trabeculae in a desmoplastic stroma. (d) Reactivity for immunohistochemical marker PAX8 (illustrated) can be helpful in establishing a diagnosis of collecting duct carcinoma (rather than urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation)

Importantly, as collecting duct carcinomas are rare and represent a diagnosis of exclusion, metastatic adenocarcinoma must be ruled out before establishing such a diagnosis. Metastatic carcinoma can be favored when the histology does not conform to any of the known subtypes of urothelial carcinoma or RCC, and when multifocality is documented, clinically, grossly, or microscopically. Metastatic carcinomas are often associated with extensive lymphovascular invasion and interstitial growth [13]. Metastases to the upper urinary tract generally involve the ureters and may originate from primary breast, kidney, stomach, colon, and hematologic malignancies [26–28]. A careful microscopic and gross examination with appropriate clinicopathological correlation will help resolve the differential diagnosis in most cases. Renal medullary carcinoma is another differential diagnostic consideration; however, this aggressive type of renal carcinoma is uncommon and usually occurs in younger African-American patients with sickle cell disease or trait [29]. In some instances, however, immunohistochemistry may play an important ancillary role in resolving the differential diagnosis [18–21].

Histopathologic Grading

The grading scheme of urothelial tumors of the upper urinary tract is identical to that used for bladder neoplasms. Consistent with mounting evidence that flat and papillary lesions proceed from significantly different molecular pathways, papillary and flat lesions are graded separately, though the cytologic criteria used for grading are similar. The basis of classification of urothelial neoplasms of the urinary bladder was a consensus report, published in 1998, which standardized both classification and the grading system [30]. This system was provided as a consensus approach by the World Health Organization and International Society of Urologic Pathology was adopted in the WHO 2004 “Blue Book” [4]; this approach has become the international standard. Importantly, though this system was developed and implemented as a consensus approach to lower tract urothelial neoplasms, it is applied to upper tract urothelial lesions as well. Table 3.4 summarizes this classification system.

Table 3.4

Consensus for classification and grading of urothelial lesionsa

Normal urothelium |

|---|

Hyperplasia |

Flat |

Papillary |

Mixed |

Flat Lesions with Atypia |

Reactive (inflammatory) atypia |

Atypia of unknown significance |

Dysplasia |

Carcinoma in situ |

Exophytic Papillary Neoplasms |

Papilloma |

Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential |

Papillary carcinoma, low-grade |

Papillary carcinoma, high-grade |

Inverted Papilloma |

Papilloma |

Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential |

Papillary carcinoma, low-grade |

Papillary carcinoma, high-grade |

Mixed Exophytic and Endophytic |

Papilloma |

Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential |

Papillary carcinoma, low-grade |

Papillary carcinoma, high-grade |

Invasive Neoplasms |

Lamina propria invasion |

Muscularis propria invasion |

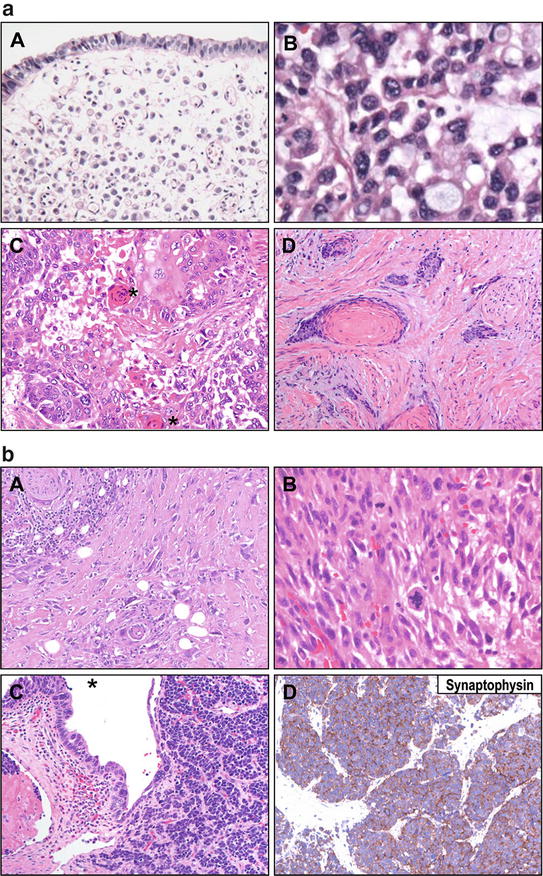

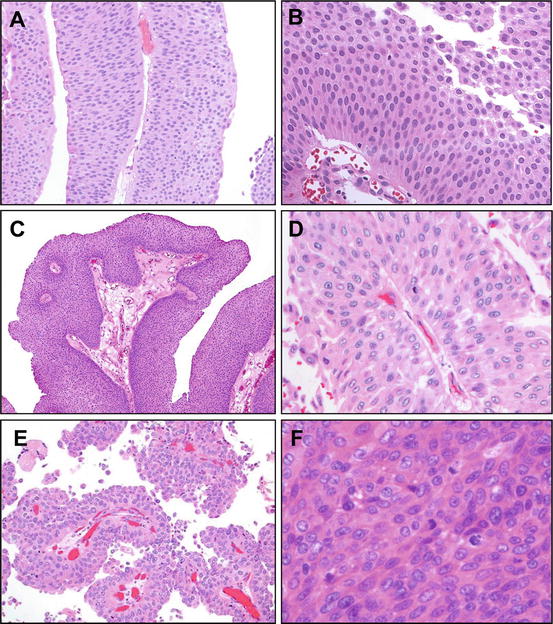

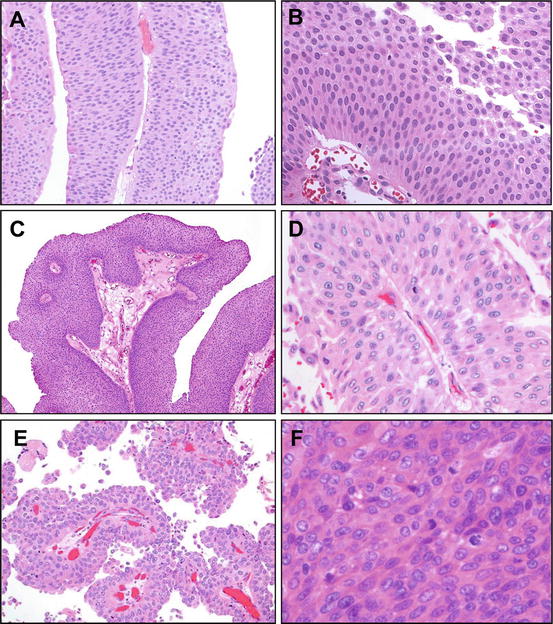

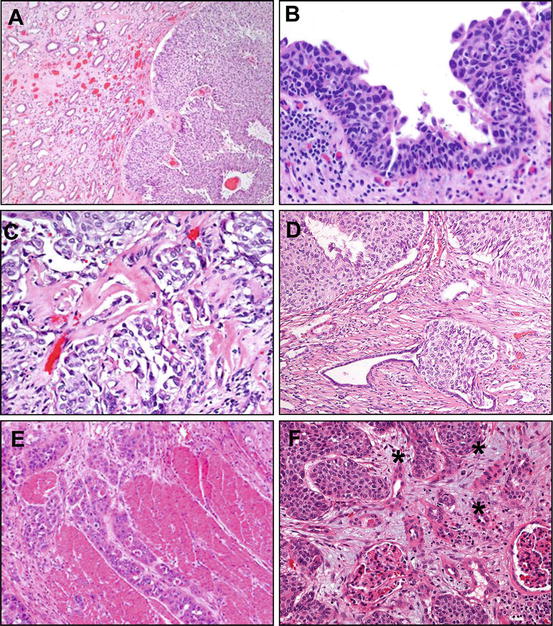

Among papillary neoplasms, broadly there are four groups of lesions. The first group includes benign neoplasms, which include papillomas and inverted papillomas (see below section on “benign tumors”), which are not graded because they are benign. Among papillary lesions with malignant potential, there are three types of lesions: papillary urothelial neoplasms with low malignant potential (PUNLMP), low-grade papillary urothelial carcinomas, and high-grade papillary urothelial carcinomas. Among flat neoplasms, two groups are identified: urothelial dysplasia and urothelial carcinoma in situ. Grading of urothelial carcinoma is based on architectural and cytologic features. These include lack of differentiation from the base to the surface, loss of polarity and cell orientation, and the nuclear features such as nuclear atypia, chromatin texture, hyperchromasia, macronucleoli, and mitotic activity (Fig. 3.4).

Fig. 3.4

Grading of papillary urothelial neoplasm. (a) Papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential (PUNLMP) demonstrates papillary growth with thickened epithelium exhibiting minimal architectural and cytologic atypia. (b) On higher power, it is apparent that urothelial cells in PUNLMP show mild atypia; mitotic figures are absent, or if present, they have a basal location. (c) Low-grade urothelial carcinoma exhibits greater architectural complexity of the papillae, with branching and fusion. (d) On higher power, there is more prominent cytologic atypia with variation in nuclear size, presence of small nucleoli, irregularities of nuclear membranes, and coarser chromatin. Importantly, the polarization of the epithelium is maintained. (e) High-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma exhibits complex architecture and the epithelium is markedly atypical, with variably sized rounded nuclei and loss of polarity. (f) On higher power, the degree of cell atypia is apparent. There is disordered architecture, cell crowding, frequent mitotic features, hyperchromasia and macronucleoli, markedly coarser chromatin, and marked nuclear irregularity

Generally speaking, the degree of cytologic atypia present is comparable between flat and papillary lesions of similar grades; for example, the cytologic atypia present in a low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is essentially equivalent to the degree of atypia present in urothelial dysplasia, though the latter flat lesion is much less prevalent. Similarly, the degree of atypia present in a high-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is equivalent to a flat urothelial carcinoma in situ. The grade that is assigned is based on the worst area present for evaluation, and combinations of lesions may be present in a given individual (i.e., a low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma with simultaneous adjacent flat urothelial carcinoma in situ or carcinoma in situ in a separate biopsy).

Invasive lesions are generally regarded as high-grade definitionally, with rare examples of invasive variants with a low-grade appearance, like the small and large nested variants of urothelial carcinoma [24, 31, 32]. For this reason, grade is generally only prognostic amongst noninvasive papillary tumors; most pT2 and higher stage tumors tend to be non-papillary and of higher grade [4]. Olgac et al. noted that although WHO/ISUP 2004 system stratifies renal pelvic tumors into distinct prognostic groups, the grade is not a significant prognostic factor on multivariate analysis [6]. Overall, and most pertinent to urothelial carcinomas of the upper tract, pelvicalyceal and ureteral urothelial carcinomas show a higher prevalence of high-grade lesions compared to bladder lesions [6].

Pathologic Stage

Pathologic staging of urothelial carcinoma of the upper tract is as outlined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer [33] and is summarized in Table 3.5. As is the case in other organ systems, lesions of the upper urothelial tract are staged by a “TNM”-based system, though given the differing anatomy and histology of pelvicalyceal lesions versus ureteral lesions, the staging of invasive lesions differs somewhat. In this system, the “T” refers to the primary tumor mass, and the letter or number associated refers to the depth of invasion. Noninvasive lesions are staged as Ta or Tis, indicative of papillary noninvasive Ta and flat noninvasive carcinoma in situ, respectively. Invasive lesions are staged as T1, T2, T3, or T4, each of which indicates varying depths of invasion. Similarly, the “N” refers to nodal status, which varies from N1-3 based on the number of involved regional lymph nodes and size of the metastasis. The “M” designation refers to distant metastasis, which may be either to a visceral site (e.g., liver) or to a lymph node that is beyond the regional lymph nodes specified by the AJCC for lesions of the renal pelvis or of the ureter (e.g., a supraclavicular lymph node). Also, similar to TNM-based systems, a lower case “p” assigned to the pT stage is indicative of pathologic staging, while a lower case “c” indicates clinical stage, as may be assigned based on examination and imaging findings before resection with pathologic staging, or in cases where pathologic staging is not possible. The TNM combination of each case may then be assigned to prognostic groupings, which vary from Stages I to IV and are of particular use for therapeutic decision-making and consideration of treatment guidelines.

Table 3.5

Pathologic staging of urothelial carcinoma of the upper tract (pTNM)a

Primary tumor (pT) |

|---|

pTX: Cannot be assessed |

pT0: No evidence of primary tumor |

pTa: Papillary carcinoma without invasion |

pTis: Flat carcinoma in situ without invasion |

pT1: Carcinoma invades subepithelial connective tissue/stroma (lamina propria) |

pT2: Carcinoma invades the muscularis propria of the ureter or pelvicalyceal mucosa |

pT3: Pelvicalyceal-based carcinoma invades through muscularis of pelvis into peripelvic fat or into the renal parenchyma |

Or |

Ureter-based carcinoma invades beyond muscularis propria into periureteric fat |

pT4: Pelvicalyceal carcinoma invades through the kidney into perinephric fat |

Or |

Ureteric carcinoma invades into adjacent organs, or through the kidney into the perinephric fat |

Regional Lymph Nodes (pN) |

pN0: No regional lymph node metastasis |

pN1: Metastasis in a single regional lymph node, 2 cm or less in greatest dimension |

pN2: Metastasis in a single regional lymph node, more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension, or multiple lymph nodes, none more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

pN3: Metastasis in a regional lymph node more than 5 cm in greatest dimension |

Distant metastasis (pM) |

Not applicable |

pM1: Distant metastasis |

TNM Descriptors (required only if applicable) (select all that apply) |

m (multiple) |

r (recurrent) |

y (posttreatment) |

In both lesions of the renal pelvis and the ureter, noninvasive lesions are staged as pTa (if papillary) or pTis (if flat carcinoma in situ), while flat or papillary lesions that invade the basement membrane and into the connective tissue of the lamina propria, whether beneath the lesion or within the stalk of papillary growths (infrequently occurring in papillary lesions), are staged as pT1. Unlike the urinary bladder, the mucosa of the ureter and renal pelvis generally does not exhibit a layer of fine, wispy muscle within the lamina propria, the so-called “muscularis mucosae,” which can render staging interpretation difficult in bladder specimens. Instead, beyond the connective tissue of the lamina propria, in both the renal pelvis (including most of its major calyces) and the ureter, is the muscularis propria or definitive muscular layer of the organ, which if invaded is staged as pT2. In the ureter, invasion through this muscularis propria and into periureteral soft (predominantly adipose tissue) is staged as pT3; invasion through muscle and soft tissue into adjacent organs is staged as pT4. In the renal pelvis, definitive invasion into the renal parenchyma is staged as pT3, while invasion through the renal parenchyma into perirenal adipose tissue is pT4.

Difficulties in Pathologic Staging of Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinomas

The staging system in its present form has the advantage of providing an internationally standardized framework so that lesions of similar extent may be classified and stratified into prognostically and therapeutically actionable groups. However, there are several areas of difficulty in the staging that require utmost attention from surgical pathologists. The first issue pertains to the remarkable degree of variability in the histology of the upper tract, in particular, in the renal pelvis. Because invasion of the muscularis propria (pT2) is an important intermediate stage between “superficial” invasion of the connective tissue of the lamina propria (pT1) and invasion of the renal parenchyma (pT3), two stages with dramatically different prognoses, the patchy to absent nature of the muscularis propria in the minor calyces provides an important conundrum in pathologic staging. Similarly, at the medullary pyramids, the urothelium essentially directly overlies the collecting system. At these sites, a carcinoma that invades the lamina propria may only have to traverse less than a millimeter or two of basement membrane before meeting diagnostic criteria for invasion of the renal parenchyma (which by definition includes the collecting ducts of Bellini); thus, extensive sampling of these tumors and a liberal use of deeper sections to evaluate the extent of invasion are critical.

For that matter, minor calyceal carcinomas may also spread into the distal renal collecting ducts in an intraepithelial or so-called “pagetoid” fashion, which may mimic the histologic appearance of renal parenchymal invasion without actually invading the basement membrane. At issue is whether definitive invasion of the basement membrane (pT1) or whether true, parenchymal invasion is present (pT3). Careful review of histologic sections is necessary to ascertain whether this pagetoid spread, which is considered pTa/pTis noninvasive disease, is present, as the prognostic and therapeutic difference between such noninvasive or superficially invasive disease and parenchymal invasion is very significant. In contrast, stage pT3 parenchymal invasion is generally destructive, multifocal to broad, and associated with stromal reaction (desmoplasia) and necrosis. Figure 3.5 provides examples of these important staging dilemmas.

Fig. 3.5

Diagnostic challenges in pathologic staging of upper tract urothelial carcinoma (see also Table 3.4). (a) An upper tract urothelial carcinoma involving the minor calyces of the kidney presents a unique challenge, given the close apposition of the luminal tumor growth and the collecting system. In this example, a noninvasive tumor is present in a minor calyx, pushing and compressing the collecting ducts of Bellini. It is important to carefully sample and evaluate the tumor and the parenchymal interface, because an invasive tumor at this site may rapidly progress from early subepithelial stromal invasion (pT1) to renal parenchymal invasion (pT3) (b) In this example, flat urothelial carcinoma in situ shows significant cellular atypia, with nuclear hyperchromasia, nucleoli, and variability in nuclear size. Despite the associated inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria, this represents in situ disease (pTis). (c) A high power field demonstrating features of early stromal invasion, with small, irregular nests and single cells, accompanied by stromal desmoplasia and retraction artifact. This tumor is stage pT1. (d) An intraductal extension of low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma is present into the collecting ducts, which does not represent true invasion, but an in situ disease (pTa or pTis, if flat lesion). A preserved layer of the tubular lining cells is apparent adjacent to the lesional cells. (e) Upper tract urothelial carcinoma invades well-formed smooth muscle bundles of ureteral muscularis propria (stage pT2). (f) Parenchymal invasion in the kidney parenchyma, illustrated at high power by individual malignant cells (asterisks) invading around a glomerulus, represents stage pT3

Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma Specimens: Processing, Sampling, and Reporting

Modern practices in urologic surgical oncology may result in a diversity of specimens being sent to surgical pathology. These range from tiny endoscopic biopsies from ureteroscopy to scant needle core biopsy fragments from image-guided biopsy protocols from interventional radiology to larger segmental ureterectomy, nephrectomy, and nephroureterectomy specimens undertaken by open, laparoscopic, and robot-assisted approaches. Fortunately, the College of American Pathologists provides evidence-based guidances in this regard, which may be referenced as a guide to establishing institutional procedures for laboratory processing of these specimens, as well as providing an outline of the reporting elements by specimen type and anatomical site [34].

Briefly, the tiny biopsies from ureteroscopic examination of upper tract lesions must be submitted entirely, with particular care in gross and histologic handling. One approach is to process such scant biopsies as cytologic specimens, using “cell block” preparations such as are used to process aspirates and other scant specimens. Other labs employ special protocols for tiny biopsy material to avoid unnecessary trim and waste of tissue when slides are being prepared. Needle core biopsies are also submitted entirely; given the shape and geometry of such specimens, multiple levels are often necessary for tissue interpretation; multiple precut levels may be made to preserve tissue should additional ancillary histochemical or immunohistochemical stains be necessary.

For larger specimens such as a segmental “partial” ureterectomy, such as may be performed for limited resection of lesions in the proximal or mid ureter, careful gross exam is important. First, the outer aspect of the specimen should be inked. The length and diameter of the specimen should be documented in the gross description, and the proximal and distal margins should be sampled en face. Then, the ureter may be opened longitudinally, with careful inspection and palpation for lesions that are not grossly apparent; carcinoma in situ, prior biopsy sites, and diminutive papillary lesions may appear as subtle mucosal abnormalities. A grossly apparent lesion should be measured, documenting its extent of surface involvement, depth of invasion, and relationship to the margins. Given the small size of these specimens, it may be advantageous to entirely submit the involved area if feasible in a reasonable number of sections. Overnight fixation in 10 % formalin is recommended to ensure appropriate sectioning of friable lesions. If gross lesions are absent, extensive sampling of the urothelium is necessary to look for in situ lesions.

Larger nephrectomy or nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff specimens also require careful gross examination, fixation, and documentation of anatomical relationships and extent of disease. Similarly, specimens should be inked on the exterior and mucosal margins (distal ureteral) and vascular (renal artery and vein) margins sampled. Sectioning should focus on demonstrating anatomical relationships most relevant to pathologic stage (relationship of tumor to lamina propria, muscular walls, renal parenchyma, perirenal or periureteral soft tissue). Additional sections of grossly uninvolved renal parenchyma and pelvicalyceal and ureteral mucosa should be taken to evaluate for glomerular disease and in situ lesions, respectively.

Definitive resection specimens such as nephroureterectomies may or may not include a lymphadenectomy as an attached or separate specimen. As in all cancer resection specimens, the perirenal and periureteral adipose tissue should be carefully examined to identify any associated lymph nodes, which should be submitted for evaluation of metastatic disease. Whether attached or separately submitted, any lymph nodes appearing grossly to be involved by metastatic disease should be measured and a representative section submitted. Any grossly negative lymph nodes should be submitted entirely, as identification of even microscopic nodal metastasis impacts the therapeutic approach. While lymph node metastasis is only identified in ~10 % of cases, in cases where lymph nodes are dissected at resection, the rate of lymph node involvement approaches one in four cases, underscoring the aggressiveness of this disease.

One harbinger of metastatic disease that may be apparent even in cases that do not show lymph node involvement is invasion of the lymphovascular space, also known as vascular invasion, lymphovascular invasion, or angiolymphatic invasion. This finding, defined as the identification outside the main tumor mass of tumor cells adherent to or floating within lymphatics and small veins, is a relatively frequent finding in urothelial carcinomas at any site. Though friable tumor cells and necrotic debris may be seen floating in vascular spaces as an artifact of sampling and histologic preparation, identification of true vascular invasion often shows the features of adherent, “vessel-shaped” balls of carcinoma, often covered with a layer of endothelial cells or adherent to the muscular wall of a vessel. In any case of suspicious but not definitive for vascular invasion, liberal use of deeper sections and even immunohistochemical stains to confirm that the lumen is indeed vascular (i.e., CD31, CD34, Erg, or other vascular markers) may be undertaken.

For that matter, a nephroureterectomy with bladder cuff is a complex specimen that includes mucosal, vascular, and radial soft tissue margins. These should be sampled with care, which, as always, requires communication with the surgical team to ensure appropriate evaluation of margin status. For margins sampled by frozen section at the time of intraoperative consultation, frozen-permanent section correlation should be undertaken as a routine quality assurance measure.

Finally, guidelines from the College of American Pathologists for evaluation of renal resection margins call for submission of tissue sections of grossly uninvolved tumor tissue for evaluation of medical renal kidney disease. Large series of renal resections find that arterionephrosclerosis, hypertensive nephropathy, or diabetic nephropathy may be present in a substantial minority of cases [35]. Such changes have been associated with a decline in renal function post-nephrectomy [36]. Histochemical stains such as PAS and Jones silver stains may be necessary to appropriately evaluate for glomerular disease. Consultation with a medical renal pathologist may be undertaken in equivocal or worrisome cases.

Pathologic Diagnostic Issues in Evaluating Ureteroscopic Biopsies and Other Upper Urinary Tract Specimens

The management of upper tract urothelial carcinoma has significantly changed with the introduction of modern imaging techniques and endoscopic visualization of all levels of the urinary tract. The development of better imaging techniques, including computed tomography urogram and magnetic resonance urogram and the use of novel endoscopic instruments, including flexible and digital ureteroscopes, has greatly improved the ability to identify and characterize these cases. These technical advances have led to increased frequency of performing ureteroscopic biopsies of the upper urinary tract. The relatively low frequency of these tumors, however, has been an impediment to conducting randomized trials that would allow definitive conclusions about staging, grading, and treatment impact on patient prognosis.

From a diagnostic standpoint, suspected upper tract urothelial carcinomas are usually evaluated by retrograde ureteropyelography, upper urinary tract cytology, and cystoureteroscopy with biopsy. Ureteroscopic biopsy is crucial for the diagnosis, follow-up, and management of the upper ureter and renal pelvis lesions and is the current gold standard for diagnosis. Ureteroscopy and pyeloscopy allow visualization of the suspected lesion and an ability to perform a targeted biopsy. The biopsy can potentially provide accurate histologic type and grade, and in some instances, such approaches may even be able to stage an upper tract urothelial carcinoma, providing parameters crucial for selection of the appropriate treatment.

Ureteroscopic biopsies are generally smaller than cystoscopic biopsies due to the size of the instrument, which results in less accurate visualization of the lesion. Therefore, the specimens from the upper urinary tract are often challenging for pathologists with regard to accurate tumor diagnosis, grading, and staging. In a great majority of cases, the evaluation is based on limited and scant amounts of tissue, often consisting of a few minute fragments of urothelium with loss of tissue orientation. Ureteroscopic biopsy provides grading accuracy of 71 % for low-grade and 80 % for high-grade urothelial neoplasms when compared to definitive assessment at resection [37, 38]. These biopsies have been reported to yield a sensitivity of 85 % for the ureter, 78 % for the renal pelvis, and 100 % for the ureteropelvic junction tumors [39]. Endoscopic biopsies have been recently reported to have a specificity of 100 % for all upper urinary tract locations and a diagnostic accuracy of 98 % [39]. Though highly specific, endoscopic biopsies result in a significant false-negative rate, owing to both sampling and diagnostic errors in the assessment of possible upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Vashistha et al. found that 87 % of tumors diagnosed on biopsy had concordant grade and 60 % had concordant pT stage, when correlated with the follow-up surgical resections and biopsies [39]. The biopsy samples with concordant tumor grades were larger (mean size 0.6 cm) than the biopsy samples with discordant grades (mean size 0.3 cm) (p = 0.04) [39], suggesting that appropriate sampling is the key in evaluating these biopsies. The grade concordance was relatively high between ureteroscopic biopsies and definitive surgical resections, particularly for larger biopsy samples. This was in contrast to the staging of the tumor, which was inaccurate, regardless of the tissue size.

Pathologists and urologists should accept negative biopsy results with caution, particularly for limited or scant biopsy specimens. In almost 1 in 4 renal pelvis/ureteral biopsies, a definitive diagnosis cannot be made because of inadequate or suboptimal biopsy or the limited size of the obtained tissue [40]. On microscopy, in cases where a definitive diagnosis could not be established, it was mainly because of the absence of recognizable papillary fronds, crush artifact, and distorted tissue architecture [40]. Major diagnostic discrepancies on expert review by a genitourinary pathologist included an overdiagnosis of a neoplastic tissue by the initial pathologist when normal tissue was examined, containing either strips of urothelium without well-developed fibrovascular cores, or polypoid ureteritis/pyelitis, or reactive urothelium [40]. Thus, caution is necessary when evaluating limited biopsy specimens obtained by ureteroscopy, especially in the absence of a clinically suspected or visualized neoplasm. The sensitivity of the cytology is related to the degree of tumor differentiation, and overall it is poor in low-grade tumors, but significantly higher in high-grade tumors [41, 42]. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of abnormalities on chromosomes 3, 7, 9, and 17 provides greater sensitivity than cytology for the detection of urothelial carcinoma while providing a similar specificity [43].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree