Despite the success of antitumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in Crohn’s disease, there remains a need for biologic therapy that targets other immune pathways of disease. Ustekinumab is a fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin antibody that targets the interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 shared P40 subunit. It has been studied in 2 phase 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in Crohn’s disease. This article reviews the clinical efficacy and safety data of ustekinumab in Crohn’s disease in anticipation of the final results of the phase III development program in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease.

Key points

- •

Ustekinumab is a fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin antibody that targets the interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 shared P40 subunit and therefore inhibits their binding to their receptor on T cells.

- •

Alternative biologic therapies are needed, because many patients do not respond to induction with antitumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy (primary nonresponders) or lose response over time (secondary nonresponders).

- •

Ustekinumab has been shown from phase 2 clinical trials in Crohn’s disease to have higher response rates compared with placebo in patients previously exposed to anti-TNF therapy.

- •

Safety data from phase 2 Crohn’s disease placebo-controlled trials do not show a higher risk of serious adverse events in ustekinumab compared with placebo.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing, and progressive inflammatory disorder of the intestine. It is the result of an abnormal response to luminal antigens leading to dysregulation of the immune system. More than 20 years ago the central role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a proinflammatory cytokine in the pathogenesis of CD, was appreciated. Blockage of TNF has since been a major advancement in the therapy for CD.

However, there are therapeutic gaps in anti-TNF therapy. Between 33% and 40% of patients do not achieve a response to induction with anti-TNF therapy in clinical trials (primary nonresponse). Of primary responders, approximately 40% subsequently lose response (secondary nonresponse). Although a proportion of these patients can be recaptured by dose escalation from both clinical trials and single-center studies, data from nonclinical trials show that a significant number of patients on regularly scheduled maintenance dosing stop infliximab because of loss of response despite dose escalation. Overall response or remission rates are lower in patients who have already been exposed to one anti-TNF who go on to another anti-TNF compared with anti-TNF–naive patients. Therefore, there is an ongoing need to develop new biologics with a different mechanism of action.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic, relapsing, and progressive inflammatory disorder of the intestine. It is the result of an abnormal response to luminal antigens leading to dysregulation of the immune system. More than 20 years ago the central role of tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a proinflammatory cytokine in the pathogenesis of CD, was appreciated. Blockage of TNF has since been a major advancement in the therapy for CD.

However, there are therapeutic gaps in anti-TNF therapy. Between 33% and 40% of patients do not achieve a response to induction with anti-TNF therapy in clinical trials (primary nonresponse). Of primary responders, approximately 40% subsequently lose response (secondary nonresponse). Although a proportion of these patients can be recaptured by dose escalation from both clinical trials and single-center studies, data from nonclinical trials show that a significant number of patients on regularly scheduled maintenance dosing stop infliximab because of loss of response despite dose escalation. Overall response or remission rates are lower in patients who have already been exposed to one anti-TNF who go on to another anti-TNF compared with anti-TNF–naive patients. Therefore, there is an ongoing need to develop new biologics with a different mechanism of action.

Role of interleukin-12 and interleukin-23 in the inflammatory pathway

Multiple human and animal models of chronic inflammatory disease highlight the central role of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 in the inflammatory pathway in CD, psoriasis, and multiple sclerosis. The IL-12 family of cytokines is responsible for stimulating innate immunity and developing adaptive immunity. This family of cytokines includes IL-23, IL-27, and IL-35. There is an increase in IL-12 production by lamina propria mononuclear cells in patients with CD compared with patients with ulcerative colitis and controls. Furthermore, a genome-wide association study has found a significant association between CD and a gene that encodes a subunit of the receptor for IL-23.

IL-12 is a heterodimer of p40 and p35 subunits. CD is characterized by a T-helper 1 (Th1) response with overexpression of interferon gamma (IFN-γ) and TNF-α. IL-12 induces the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into IFN-γ–producing Th1 cells and mediates cellular immunity.

IL-23 is a heterodimer of the same p40 subunit and a p19 subunit. IL-23 induces naive CD4+ T cells into T-helper 17 (Th17) cells. Th17 cells in turn induce the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, IL-17F, IL-6, and TNF-α.

Ustekinumab is a fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin (IgG1) antibody that targets the IL-12 and IL-23 shared P40 subunit, and by doing so inhibits their binding to their receptor on the surface of T cells, natural killer cells, and antigen-presenting cells. In clinical trials it has been administered either intravenously or subcutaneously.

Clinical trials in CD

Clinical Efficacy

In a phase 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, crossover trial, 104 patients (population 1) with moderate to severe CD (CD Activity Index [CDAI] score of 220–450) were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 groups: subcutaneous (SC) placebo at weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3, followed by 90 mg ustekinumab at weeks 8, 9, 10, and 11; SC 90 mg ustekinumab at weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3, then placebo at weeks 8, 9, 10, and 11; intravenous (IV) placebo at week 0, followed by 4.5 mg/kg ustekinumab at week 8; or IV 4.5 mg/kg ustekinumab at week 0, followed by placebo at week 8. This complicated dose-finding study enrolled both anti-TNF therapy–naive patients and those who had been exposed to anti-TNF therapy. Patients who were on submaximal doses/regimens of infliximab or who had a history of infliximab intolerance made up 47% of this group (49 of 104). As part of the same study, 27 patients (population 2) who were primary or secondary nonresponders to infliximab despite dose escalation were randomly assigned to an open-label study of either SC 90 mg ustekinumab at weeks 0, 1, 2, and 3, or IV 4.5 mg/kg ustekinumab at week 0.

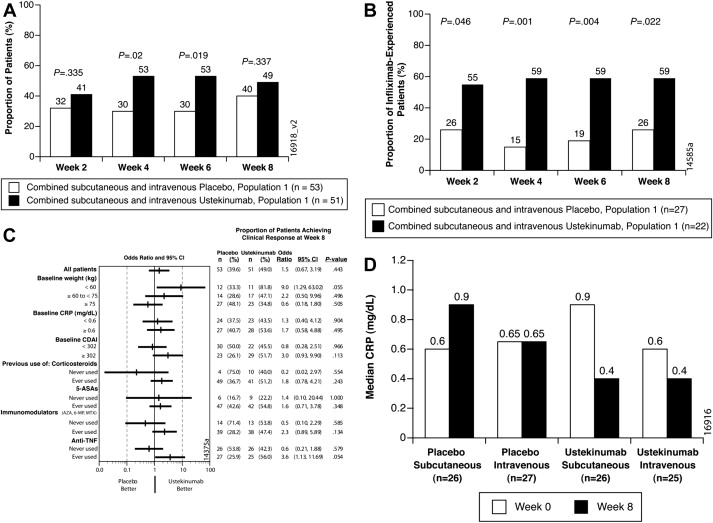

In the placebo-controlled study (population 1) there were no significant differences in the primary end point of clinical response at week 8, defined as a reduction of greater than or equal to 25% and greater than or equal to 70 points from baseline CDAI, between the combined ustekinumab group (49%, 25 of 51) and the combined placebo group (40%, 21 of 53) ( P = .34). Although this study evaluated the primary end point at week 8, at the earlier time points of weeks 4 and 6, 53% of patients in the combined ustekinumab group were in clinical response compared with only 30% in the placebo group ( P <.05), suggesting that week 8 may not have been the optimal time point for evaluation of response ( Fig. 1 A).

In patients who have previously been exposed to infliximab at every time point of clinical assessment, weeks 2, 4, 6, and 8, there was a significant larger proportion of patients in the combined ustekinumab group who achieved clinical response compared with the combined placebo group ( P <.05) (see Fig. 1 B). In a predefined subgroup analysis, patients on ustekinumab with a history of exposure to anti-TNF had an odds ratio compared with placebo of 3.6 (95% confidence intervals [CI], 1.1–11.7; P = .05) (see Fig. 1 C) for clinical response at week 8. Median C-reactive protein (CRP) levels in the ustekinumab group decreased from week 0 to week 8 (see Fig. 1 D). The investigators further explored the relationship between CRP and previous anti-TNF therapy. At week 8 there was a larger difference in clinical response between ustekinumab and placebo groups in the subgroup of infliximab-experienced patients with a high baseline CRP. Overall in patients with a baseline CRP less than 10 mg/L there was no difference in response rates: 43% in patients given placebo and 41% in patients given ustekinumab at week 8 ( P = .83). However, in the group of patients previously exposed to infliximab with baseline CRP greater than 10 mg/L, the response rate at 8 weeks was 75% compared with 20% in the placebo group ( P = .05).

The clinical responses at week 8 to SC and IV ustekinumab in the open-label trial (population 2) were 43% and 54%, respectively. At every time point of clinical assessment, the response and remission rates were higher in the IV group compared with the SC group.

Ustekinumab in CD was further studied in a phase 2b 36-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 8-week induction and 26-week maintenance trial. All patients enrolled in this trial had to meet prespecified definitions of anti-TNF primary nonresponse, secondary nonresponse, or intolerance during anti-TNF therapy. During the induction phase, 526 patients were randomly assigned to receive a weight-based dose of IV ustekinumab (1 mg/kg, 3 mg/kg, or 6 mg/kg) or placebo. Responders and nonresponders were separately randomized to SC ustekinumab 90 mg or placebo at weeks 8 and 16. The primary end point was clinical response at week 6 defined as greater than or equal to a 100-point decrease from baseline CDAI.

This study met the primary end point, because 39.7% of patients at 6 mg/kg achieved clinical response at week 6 compared with 23.5% of patients receiving placebo ( P = .005) ( Fig. 2 A).

However, clinical remission rates at week 6 were similar between the ustekinumab and placebo groups (see Fig. 2 B). In the patients given 6 mg/kg ustekinumab, 12.2% were in clinical remission at week 6 compared with 10.6% of patients given placebo at week 6 ( P = .68). The investigators hypothesized that clinical remission at week 6 was difficult to achieve, because the high median baseline CDAI score of 330 would have required a 180-point reduction to meet the end point of clinical remission (CDAI<150).

Among patients with a response to ustekinumab in the induction phase, 69.4% of patients receiving 90 mg of ustekinumab in the maintenance phase continued to have a clinical response at week 22, compared with 42.5% of patients receiving placebo at week 22 ( P <.001) ( Fig. 3 A). Among patients with a response to ustekinumab in the induction phase, 41.7% of patients receiving 90 mg of ustekinumab in the maintenance phase were in clinical remission at week 22, compared with 27.4% of patients receiving placebo ( P = .03) (see Fig. 3 B).