Truncal Vagotomy with Gastrojejunostomy

Richard H. Turnage

Indications

Gastrojejunostomy is most commonly used to treat patients with gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) of whom nearly two-thirds will have malignancies of the distal stomach, pancreas, or duodenum. The most common benign causes of GOO are peptic ulcer disease (PUD), caustic strictures, and Crohn’s disease. Less common benign etiologies include tuberculosis, chronic pancreatitis, benign gastric polyps, and Bouveret’s syndrome (i.e., obstruction of the pylorus by a gallstone). Although not amenable to gastrojejunostomy, systemic medical diseases, most notably diabetes mellitus, are important causes of impaired gastric emptying.

Complete resection is the treatment of choice for patients with upper gastrointestinal (UGI) malignancies. Unfortunately, locally advanced or metastatic disease precludes this approach in a significant percentage of these patients. Although noncurative gastric resection is an important option for managing symptomatic patients with advanced gastric cancer, this approach is less often feasible for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Endoscopic stenting of malignant obstructions of the distal stomach and duodenum is an important option in managing patients with GOO who have relatively short life expectancies, such as those with metastatic disease or poor performance scores. Advances in imaging with multidetector computed tomography have significantly improved preoperative identification of patients with advanced disease such that gastrojejunostomy is now used most often for symptomatic patients with unresectable cancer for whom endoscopic stenting has been unsuccessful or patients who are unexpectedly found to have advanced disease during exploratory laparotomy for cure.

PUD is the most common benign cause of mechanical GOO. Medical management combined with endoscopic balloon dilation results in durable relief of obstructive symptoms in about 70% of cases. This approach is particularly effective for patients with GOO due to Helicobacter pylori-associated ulcers. In contrast, NSAID-induced ulcers seldom resolve with nonoperative approaches. Young age, long duration of symptoms, the need for repeated endoscopic balloon dilatations, and the continuous use of NSAIDs predict the need for surgical management. Surgical approaches to patients with GOO from PUD include truncal vagotomy and antrectomy or truncal vagotomy and a drainage procedure (either pyloroplasty or gastrojejunostomy). Truncal vagotomy and antrectomy has the lowest rate of recurrent ulcer disease. The magnitude of the operation and the consequent operative risk necessitates other strategies in patients with significant medical comorbidities as well as those patients who are found intraoperatively to have significant inflammation and scarring of the distal stomach and duodenum. Truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty is suitable for patients with minimal inflammation or deformity of the pylorus or proximal duodenum, thereby permitting a tension-free transverse closure of the pylorus. Unfortunately, this is often not the case, making truncal vagotomy and gastrojejunostomy (TV & GJ) the best option.

Lastly, the ingestion of strong acidic solutions causes strictures in the prepyloric region of the stomach leading to GOO. Kochhar et al. have described excellent short- and intermediate-term outcomes with endoscopic balloon dilation of caustic-induced gastric strictures. Others have managed these patients with distal gastrectomy. Thus, gastrojejunostomy is reserved for those patients with prepyloric strictures who have failed endoscopic balloon dilation and are poor operative candidates for distal gastrectomy.

Contraindications

The principal contraindications to the performance of a TV & GJ are technical. If a truncal vagotomy is required in a patient who has had a previous operation in the esophageal hiatus (e.g., fundoplication or prior vagotomy), a thoracoscopic approach to vagotomy may be preferable to allow dissection in tissue planes free from scarring and inflammation. In patients with ulcer disease or other benign causes of GOO, the enlarged stomach makes the performance of a tension-free gastrojejunostomy relatively straightforward. However, peritoneal metastases in patients with gastric or periampullary cancers may cause foreshortening of the small bowel mesentery, rendering it difficult to achieve a tension-free anastomosis between the stomach and the jejunum.

The initial management of a patient with GOO consists of intravascular volume and electrolyte resuscitation, nutritional repletion, and identification of the underlying cause of the obstruction. Significant intravascular volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities, especially hyponatremia, hypokalemia, and hypochloremia, are common and are readily corrected by the intravenous infusion of a normal saline solution with potassium chloride. The loss of gastric secretions from persistent vomiting may also cause a significant metabolic alkalosis which will correct with the administration of normal saline and potassium chloride. Gastric aspiration via a nasogastric (NG) tube will decompress the dilated atonic stomach and improve the patient’s abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting. The intravenous administration of a proton pump inhibitor will reduce gastric acid secretion, and the administration of total parenteral nutrition via a central venous catheter will begin to correct the patient’s calorie and protein deficits.

After resuscitating the patient, esophagogastroduodenostomy should be performed to determine the etiology of the obstruction. An ulcer or mass in the stomach or a suspicious lesion in the duodenum necessitates endoscopic biopsy. Biopsy of the gastric mucosa will document the presence of Helicobacter pylori—eradication of which will facilitate healing of benign ulcers and in many cases relieve the patient’s obstruction. If a malignancy is identified or if endoscopy is indeterminate, computed tomography will characterize the lesion by determining its size, relationship to surrounding structures, and the presence or absence of visceral metastases.

Patients should receive a prophylactic dose of antibiotics intravenously 30 to 60 minutes prior to the incision. It is the author’s preference to use cefoxitin in those patients who are not beta lactam allergic. Subcutaneous injection of 5,000 units of heparin sulfate administered preoperatively will reduce the risk of postoperative pulmonary embolism. The risk of aspiration during the induction of anesthesia and intubation may be diminished by the evacuation of gastric contents via the NG tube and posterior pressure on the cricoid cartilage.

Positioning

TV & GJ may be performed by either a laparoscopic or an open approach. Depending on the surgical approach, the patient can be placed in the supine or lithotomy position. For minimally invasive gastric approaches, if the patient is in a supine position, the operating surgeon stands on the right side of the patient while the assistant is on the contralateral side. If the lithotomy position is used, the surgeon stands between the legs. The patient is secured to the table with two safety straps, a foot board, and all of their bony prominences are well padded. For an open approach the patient is placed in the supine position with the head of the operating table elevated to facilitate exposure of the organs within the upper abdomen. The lower chest and entire abdomen is prepped with a chlorhexidine-alcohol solution and then draped with sterile towels and sheets.

Technique

The open approach will be presented in detail, but, ultimately, the same operative steps are generally true for a laparoscopic approach (for details on placement of laparoscopic trocars and specific techniques see Chapters 4, 6, and 7). When the laparoscopic approach to this procedure is used, a low threshold for conversion to an open procedure should exist when visualization of important structures are impaired. Standing on the patient’s right side, the surgeon makes an upper midline incision from the xiphoid to the umbilicus. The incision is extended through the subcutaneous tissue and linea alba until the peritoneal cavity is entered. The ligamentum teres is ligated with 2-0 silk and divided and the falciform ligament is released from the anterior abdominal wall. The abdominal cavity is carefully explored and then attention is directed to the upper abdomen. In patients with GOO from ulcer disease, the location of the ulcer, extent of inflammation, and the patient’s general medical condition will influence the choice of gastric resection versus a drainage procedure. For patients with malignancies, the first steps of the operation are to determine the resectability of the tumor and document the presence or absence of peritoneal or visceral metastases. The ability to mobilize an adequate length of jejunum for the performance of a tension-free gastrojejunostomy is ascertained at this time.

Truncal Vagotomy

A self-retaining abdominal wall retractor is placed to allow lateral retraction of the rectus abdominis muscles and anterior and superior retraction of the costal margins. The left lobe of the liver is mobilized by incising the avascular left triangular ligament with an electrocautery. This is facilitated by downward traction on the left lobe of the liver with the right hand while the index finger is placed behind the triangular ligament to protect the underlying structures. The triangular ligament is incised from lateral to medial until the left lobe of the liver can be folded upon itself thereby exposing the underlying gastroesophageal junction. The liver is covered with a moist laparotomy sponge and a Harrington-type blade for the self-retaining abdominal wall retractor is used to hold the left lobe of the liver to the patient’s right side. In a laparoscopic approach the triangular ligament is left intact and the lateral segment of the left lobe of the liver is elevated with a self-retaining retractor such as a Nathanson retractor.

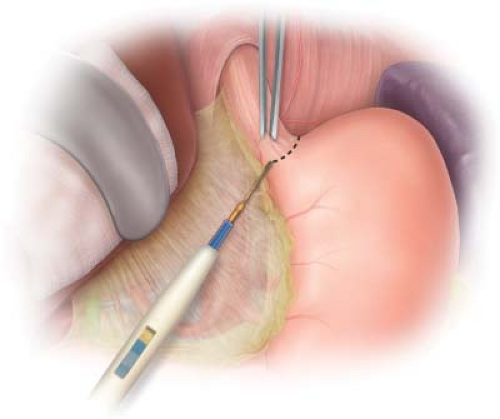

Figure 1.1 Transverse incision of the peritoneum and phrenoesophageal ligament to expose the underlying intra-abdominal esophagus and esophageal hiatus. |

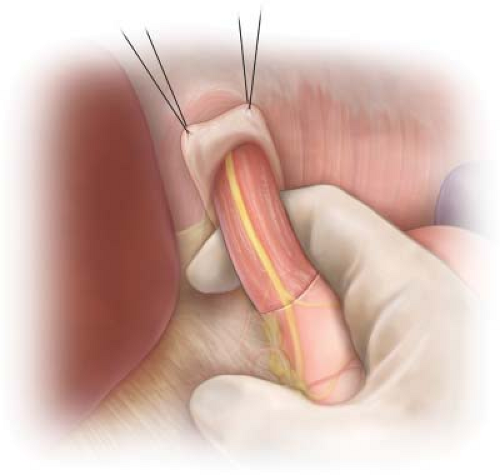

The peritoneum overlying the distal esophagus is grasped with DeBakey forceps and incised perpendicular to the long axis of the esophagus with Metzenbaum scissors or the electrocautery. The peritoneum and the underlying phrenoesophageal ligament are incised sufficiently to allow identification and mobilization of the esophagus (Fig. 1.1). This will usually include opening the medial most aspect of the gastrohepatic ligament on the right. The left gastric artery and its esophageal branch are left undisturbed. It is not necessary to divide the short gastric vessels on the left. By opening the incised peritoneum and phrenoesophageal ligament, the surgeon is able to free the distal 5 or 6 cm of the esophagus from the surrounding tissues by blunt dissection with his/her index finger. Once completed, the esophagus may be encircled with the index finger passed from the patient’s left side to the right (Fig. 1.2). The esophagus with the NG tube is felt anterior to the surgeon’s finger and the abdominal aorta is appreciated posterior. A 1-inch Penrose drain is then passed behind the esophagus to encircle it. Downward and slight anterior traction on the esophagus using the Penrose drain will facilitate blunt dissection of the distal 8 to 10 cm of esophagus from surrounding soft tissue, thus exposing the right crus of the diaphragm and the tissue lateral and posterior to the esophagus.

Figure 1.2 Mobilization of the distal 5 to 6 cm of esophagus from the soft tissue of the esophageal hiatus by passing the surgeon’s index finger from the left to the right side of the esophagus. |

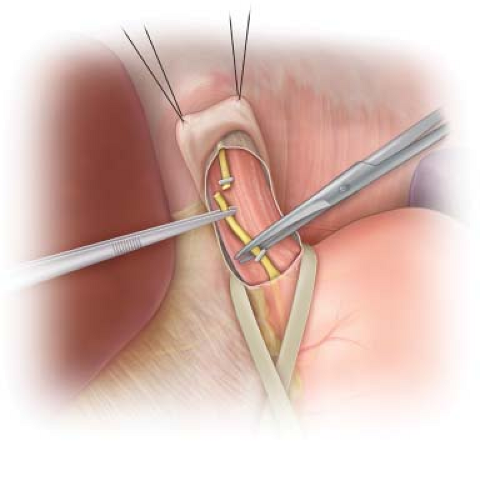

Figure 1.3 Identification of the left vagus nerve on the anterior surface of the esophagus, just to the right of the midline. The nerve is clipped with a medium stainless steel clip and then divided. |

Identification of the vagus nerves is accomplished by passing the tip of the index finger over the anterior surface of the esophagus while placing downward traction on the Penrose drain. The vagus nerve fibers will present as tense, wire-like structures passing parallel to the long axis of the esophagus; the nerve fibers have been likened to “banjo strings.” In addition to the larger left and right vagus nerves, there are often multiple smaller nerve fibers traversing the surface of the esophagus and the esophageal hiatus. In an anatomic study of the vagus nerve at the esophageal hiatus, Skandalakis et al. found four or more vagal trunks in 12% of their dissections.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree