Truncal Vagotomy with Antrectomy and Billroth I Reconstruction

Stanley W. Ashley

Thomas E. Clancy

Vagotomy has been recognized as a means of reducing gastric acidity, and thus it has been used in treating gastroduodenal ulcers since the early years of the 20th century. The use of vagotomy for peptic ulcer disease was found to be associated with delayed gastric emptying, so a gastric drainage procedure was added. The combination of truncal vagotomy and antrectomy, whereby the gastrin-producing antrum is removed, was subsequently proposed. Alternatives to truncal vagotomy to spare the celiac and hepatic branches (proximal selective vagotomy) or with preservation of vagal innervations of the antrum (highly selective vagotomy) have been proposed to mitigate postvagotomy complications of dumping and diarrhea. Still, the loss of receptive relaxation and gastric accommodation with all procedures makes some drainage procedure desirable.

The past few decades have seen a dramatic decrease in the role of surgical management of uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease. While operative management was previously routine for gastric and duodenal ulcers, the use of acid-suppressing medications such as histamine-2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors, as well as the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection, has made many such procedures rare. Surgical management of peptic ulcer disease is now predominantly limited to complications of the disease, such as hemorrhage, perforation, and obstruction. This approach largely avoids the use of acid-reducing operations. Still, acid-reducing procedures may play an important role in the management of complicated and refractory ulcer disease, particularly in patients who have failed acid-suppressing medications.

Truncal vagotomy remains an important option for complicated peptic ulcer disease, particularly in the acute setting with a medication-refractory patient. Antrectomy will remove approximately 35% of the stomach, including all of the nonparietal cell portion of the stomach. This will allow resection of a distal gastric or prepyloric ulcer. Given very effective antisecretory medications and antibiotics to treat H. pylori, truncal vagotomy and antrectomy is primarily useful in the setting of pyloric outlet obstruction with recurrent ulcer symptoms or peptic ulcer disease complicated by bleeding or perforation. Reconstruction of intestinal continuity can be performed via gastroduodenostomy (Billroth I) or loop gastrojejunostomy (Billroth II).

The indications for truncal vagotomy, antrectomy, and Billroth I gastroduodenostomy are as follows:

prepyloric ulcer

gastric ulcer

peptic ulcer disease with gastric outlet obstruction

recurrent ulcer after treatment with antisecretory medications

emergency treatment of complicated ulcer disease, in a patient who is refractory to antisecretory medications

Preoperative evaluation should include detailed imaging and laboratory data as well as endoscopic evaluation. In the case of complicated peptic ulcer disease, emergency surgery may not allow extensive preoperative workup. Preoperative laboratory indices should include hematocrit, bleeding parameters, basic chemistries, and tests of nutritional reserve given the risk of preoperative malnutrition and postoperative ileus complicating major gastrointestinal surgery.

Endoscopy is essential for the evaluation of the patient with bleeding secondary to peptic ulcer disease; endoscopic management is often sufficient to manage bleeding without surgery. Surgery is required for bleeding in the unstable patient, after extensive transfusion (over 6 units of blood), or for rebleeding after initial endoscopic management. Precise localization of the bleeding source is important.

Endoscopy is also important in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection. In patients with refractory peptic ulcer disease, endoscopy is important for biopsy to rule out occult gastric malignancy. Workup should include biopsies of the ulcer base and surrounding gastric mucosa. Endoscopy also has a role in the documentation of healing of gastroduodenal ulcers after the initiation of antisecretory medications, as failure of ulcers to heal may portend occult malignancy.

Imaging to include a chest x-ray and CT scan of the abdomen is useful to detect potential metastatic disease when malignancy is considered.

Pertinent Anatomy

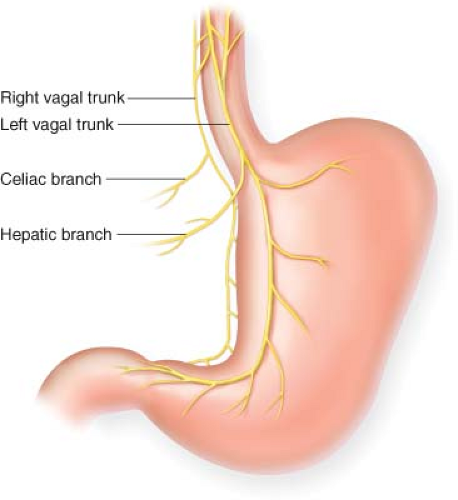

The vagal nerves, a plexus around the intraabdominal esophagus, will join to form two trunks at the esophageal hiatus. The anterior (left) vagus nerve is positioned along the anterior wall of the esophagus, while the posterior vagus is found between the posteromedial wall of the esophagus and the right crus of the diaphragm (Fig. 3.1).

Positioning

Patients are positioned in the supine position. As access to the upper stomach and distal esophagus is critical, an upper midline incision to the xiphoid process is typically utilized. A bilateral subcostal incision, providing excellent exposure to the duodenum, may compromise optimal exposure of the upper abdomen. The abdomen is prepped from the low chest to the pubis.

Mild reverse Trendelenburg position is useful, and a nasogastric tube not only decompresses the stomach but will also allow easier identification of the esophagus. Mobilization of the left lobe of the liver by dividing the triangular ligament is performed selectively; although this maneuver may aid exposure of the gastroesophageal junction

in some patients, a large or redundant left lateral segment may be held in place by the triangular ligament and exposure may be impeded by its division in some patients.

in some patients, a large or redundant left lateral segment may be held in place by the triangular ligament and exposure may be impeded by its division in some patients.

Technique

Vagotomy

Mobilization of the liver medially or superiorly may be necessary for optimal visualization of the gastroesophageal junction. The left triangular ligament of the liver can be divided with cautery to facilitate medial rotation of the left lateral segment of the liver.

The distal esophagus is exposed by incising the peritoneal covering of the gastroesophageal junction with cautery, incising the peritoneum from the lesser curvature to the cardiac notch at the greater curvature. Gentle blunt dissection is used to surround the esophagus. A Penrose drain is placed around the distal esophagus for retraction. Care should be taken to place the Penrose drain at a sufficient distance from the esophagus to include the vagal trunks. The posterior vagal trunk may be palpated during this maneuver as a tight cord. For complete vagotomy, the distal esophagus must be mobilized proximally and stripped of peritoneal attachments for approximately 5 cm.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree