Truncal Vagotomy and Pyloroplasty

David W. McFadden

Edward C. Borrazzo

Vladimir Neychev

Introduction

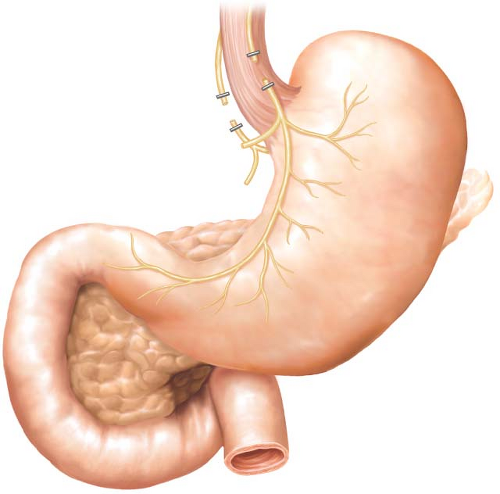

The word vagotomy technically means vagal nerve transection, thus interrupting sensory and motor impulses to the stomach and gastrointestinal tract. However, a 1- to 2-cm section of each nerve is usually resected. Although the proper term for resection should be “vagectomy,” vagotomy is the much more commonly used term (Fig. 2.1). Its purpose is the elimination of direct cholinergic stimulation of gastric acid secretion. Vagal fibers innervate the stomach and play a major role in the cephalic phase of gastric acid secretion by their release of acetylcholine, which stimulates acid secretion from the parietal cell. The distal portion of the anterior and posterior vagal trunks also sends motor branches to the antrum and pylorus. The celiac branch of the posterior vagus stimulates small intestine motility as well. Gastric motility is affected by the antral and pyloric branches of the vagus that stimulate peristaltic activity of the antrum and pyloric relaxation. The vagus also stimulates receptive relaxation of the fundus, resulting in accommodating intake with no corresponding pressure increase.

Vagotomy results in a 75% decrease in basal acid secretion and a 50% decrease in maximum acid output. Additionally, due to the loss of reflex relaxation of the gastric fundus, increased gastric capacity after eating is attended by a rise in pressure, resulting in rapid emptying of liquids. Vagotomy also disturbs distal stomach motility, resulting in difficulty in emptying solids. Because of these changes, approximately 20% to 30% of vagotomy patients develop gastric atony, which may lead to stasis and chronic abdominal pain and distention. Hence, it is surgical dogma that after truncal vagotomy patients require a “drainage” procedure to offset the nonrelaxing, obstructing pylorus. Although four kinds of vagotomy have been described in the surgical literature—truncal, selective, highly selective, and supradiaphragmatic—truncal and highly selective vagotomy are generally used to treat peptic ulcer disease. Selective and supradiaphragmatic vagotomies are rarely used.

In Dragstedt’s initial and seminal series of truncal vagotomy for the treatment of duodenal ulcer disease in 1943, nearly one-third of his patients experienced postoperative nausea, vomiting, and distention. His subsequent investigations revealed that truncal vagotomy denervated the antrum and pylorus resulting in a functional gastric

outlet obstruction. It became apparent that a “drainage” procedure was necessary to avoid the symptoms of gastric stasis. Therefore, any patient who undergoes truncal, selective, or supradiaphragmatic vagotomy should undergo a drainage procedure to facilitate gastric emptying. Drainage procedures can be divided into two categories: pyloroplasties and gastrojejunostomy. Pyloroplasty is the favored approach as it maintains the original anatomy, is simple, and is accompanied by less bile reflux than gastrojejunostomy. Currently over 90% of all drainage procedures are variations of pyloroplasty. Pyloroplasty was originally described independently by two surgeons, Heineke and Mikulicz, in 1888, decades before its routine application for drainage after vagotomy. The Heineke–Mikulicz (HM) pyloroplasty is popular because it is technically uncomplicated, widely applicable, and associated with few complications. In children with pyloric stenosis, pyloromyotomy is usually performed, leaving the mucosa intact. This approach in adults is often unsuccessful as the duodenal mucosa is more adherent to the muscle layer and the intestinal lumen is often entered during the myotomy.

outlet obstruction. It became apparent that a “drainage” procedure was necessary to avoid the symptoms of gastric stasis. Therefore, any patient who undergoes truncal, selective, or supradiaphragmatic vagotomy should undergo a drainage procedure to facilitate gastric emptying. Drainage procedures can be divided into two categories: pyloroplasties and gastrojejunostomy. Pyloroplasty is the favored approach as it maintains the original anatomy, is simple, and is accompanied by less bile reflux than gastrojejunostomy. Currently over 90% of all drainage procedures are variations of pyloroplasty. Pyloroplasty was originally described independently by two surgeons, Heineke and Mikulicz, in 1888, decades before its routine application for drainage after vagotomy. The Heineke–Mikulicz (HM) pyloroplasty is popular because it is technically uncomplicated, widely applicable, and associated with few complications. In children with pyloric stenosis, pyloromyotomy is usually performed, leaving the mucosa intact. This approach in adults is often unsuccessful as the duodenal mucosa is more adherent to the muscle layer and the intestinal lumen is often entered during the myotomy.

Management

Three different types of pyloroplasty have been described. Truncal vagotomy and pyloroplasty is a relatively simple procedure, but there are some nuances that will prevent recurrences and complications. It can be performed laparoscopically or with

open surgical technique. Indications most often include persistent ulcer disease refractory to medical therapy.

open surgical technique. Indications most often include persistent ulcer disease refractory to medical therapy.

Vagotomy

Exposure is through an upper midline incision for the open technique or with five trocars positioned in a similar way as for any laparoscopic foregut operation (see Figs. 2.1 and 2.2). First, attention is turned toward the gastroesophageal junction. We use a Thompson retractor to elevate the left lateral segment of the liver when performing surgery laparoscopically, or a Bookwalter or Omni retractor for open surgery. For open surgery, the left triangular ligament is incised using cautery to allow medial retraction of the left lateral segment of the liver. This step is not necessary in the laparoscopic approach since the liver is elevated in a cephalad direction to attain access to the diaphragm hiatus. The gastrohepatic ligament is divided. Also, division of the superior attachments of the gastrosplenic ligament makes encircling the esophagus easier. The esophagus is then encircled with a Penrose drain for retraction. The crura are separated from the esophagus, and the esophagophrenic ligament is incised to expose the anterior esophagus. This step is especially important in patients with hiatal hernia. Occasionally, the gastroesophageal fat pad must be dissected if prominent, exposing the GE junction anteriorly. Again, if the lower esophagus is exposed in the mediastinum, the vagotomy may be performed superior to the GE junction fat pad.

Attention is then turned toward the anterior branch of the vagus nerve (Fig. 2.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree