Fig. 4.1

Pyramid of the primary treatment of the prostate cancer

4.1.1 Localized Disease

This includes all the tumours not extending beyond the prostate capsule, that is, cT1-T2, N0, M0 disease. The proposed treatment modalities differ according to D’Amico risk groups’ stratification.

4.1.1.1 Low-Risk Patients

cT1–cT2a, Gleason’s score (GS) <7 and PSA ≤ 10 ng/ml.

Observation

Two strategies apply when deciding not to treat the patient actively: watchful waiting (WW) and active surveillance (AS).

Watchful Waiting (WW)

Watchful waiting (WW) is proposed for patients with T1a (tumour seen in ≤5 % of tissues resected) with <10 years life expectancy (LE). The principle of a WW strategy is simply to leave the patient ‘alone’ as long as he is asymptomatic, and to wait for the disease to eventually become symptomatic or metastatic where only palliative treatment will be offered [1]. The reason for advocating WW is the expected indolent course of the low risk disease with a short life expectancy. The rationale is not to endanger a patient’s life with a major curative treatment and not to lower his quality of life (QoL).

WW may also be proposed to unfit asymptomatic patients at any stage of the disease, except for metastatic disease.

Active Surveillance (AS)

Active surveillance (AS) or active monitoring is indicated for patients with > 10-year life expectancy. The tumour behaviour is closely monitored and when treatment is initiated, it will be with a curative intent. This strategy avoids over treating indolent tumours and prevents treatment-related complications in the younger age group [2]. During AS, it is recommended to repeat [3]:

The PSA every 3-6 months for the PSADT calculation,

A DRE every 6-12 months, and

The TRUS-guided biopsy between 3-18 months after the first set to rule out undergrading of the tumour.

AS should not be considered when there is more than 50 % prostate cancer (PC) involving any needle biopsy core or more than 3 positive cores in the 12-core protocol [4] or >3 mm of tumour in a core [5].

Pathologists at Johns Hopkins Hospital recommend including the intervening normal prostatic tissue when there are two or more malignant foci in one core by measuring the entire stretch between the extreme ends of the most far apart cancer foci. This was shown to be a better predictor of organ-confined disease and surgical margin positivity in subsequent prostatectomy specimens [6].

AS appears to be the only indication for repeat biopsies after a positive one and before any curative therapy.

In a large retrospective study, patients primarily on AS have shown a 43 % 10-year treatment-free survival, but 100 % 10-year PC-specific survival [7]. However, a great number of patients requested active treatment only because of anxiety, although objective signs of progression often had not indicated a need to shift to radical treatment.

Active Treatment

Radical Prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is an option for T1a in younger patients with long life expectancy.

RP is the standard for all other stages of the low risk D’Amico group (T1b–c and T2a, GS <7 and PSA ≤10 ng/ml) if life expectancy is >10 years [3, 8].

However, RP requires a patient’s informed consent with regard to the complications, especially the possibility of unfavourable outcomes on erectile function and urinary continence [8]. Recently, a very large retrospective study comparing RP with radiotherapy (RT) and observation confirmed the superiority of RP in the overall survival in men with >10 years LE [9].

The techniques of performing RP may be by open surgery (perineal or retropubic), standard laparoscopic prostatectomy (LP) (transperitoneal or extraperitoneal) or robotic assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) (also transperitoneal or extraperitoneal). No superiority was found in the oncological or functional outcomes in any of the approaches in one meta-analysis [10]. Another meta-analysis has suggested the superiority of RALP compared to LP and open procedures in terms of positive surgical margins and perioperative complications [11]. Neurovascular bundles (NVB) preservation is the rule in all low-risk, sexually active patients, in order to prevent or minimize the complications on erectile function and urinary continence. The proposed nerve-preserving techniques consist either of an intrafascial or an interfascial dissection, with the latter appearing to be a better compromise between the functional and oncological outcomes [12].

The advent of robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery has brought a substantial contribution to the nerve-preserving techniques (Fig. 4.2). However, it is worth remembering that the da-Vinci robot is still unavailable in many parts of the world, and its high cost may continue to be an obstacle for a large number of institutions, especially in developing countries. On the other hand, the learning curve and technical difficulties of LP continue to challenge many surgeons despite its successful introduction by early pioneers more than 15 years ago [13, 14]. Finally, supporters of the open RP are not yet convinced by the superiority of the novel techniques and the former operation remains the preferred technique in few institutions, including in advanced countries [15].

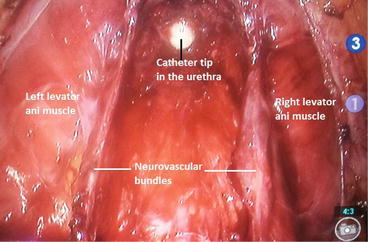

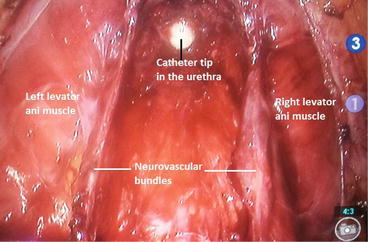

Fig. 4.2

RALP: View of the bilaterally preserved neurovascular bundles before urethro-vesical anastomosis

Extended pelvic lymph nodes dissection (ePLND) with no frozen biopsy study is only optional in low risk cancers, because the nodal disease risk is very low (<7 %) [16].

This degree of risk does not justify the increased morbidity: lymphocoele, lymphoedema, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, ureteral injury, obturator nerve injury, iliac vessels injury etc. [17, 18].

Major surgery is contraindicated in patients in the anaesthetic categories of ASA 3 and 4 according to the classification adopted by the American Society of Anesthesiologists in 1963 and last approved in 2014 (Table 4.1) [19].

Table 4.1

ASA physical status classification system [19], last approved by the ASA House of Delegates on October 15, 2014

ASA Physical status classification | Definition | Examples, including, but not limited to: |

|---|---|---|

ASA I | A normal healthy patient | Healthy, nonsmoking, no or minimal alcohol use |

ASA II | Mild systemic disease | Mild diseases only with substantive functional limitations. Examples include (but not limited to): current smoker, social alcohol drinker, pregnancy, obesity (30<BMI<40), well-controlled DM/HTN, mild lung disease |

ASA III | Severe systemic disease | Substantive functional limitations; one or more moderate to severe diseases. Examples include (but not limited to): poorly controlled DM or HT, COPD, morbid obesity (BMI≥40), active hepatitis, alcohol dependence or abuse, implanted pacemaker, moderate reduction of ejection fraction, ESRD undergoing regularly scheduled dialysis, premature infant PCA < 60 weeks, history (>3 months) of MI, CVA, TIA, CAD/stents. |

ASA IV | Severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | Examples include (but not limited to): recent (<3 months) MI, CVA, TIA, or CAD/stents, ongoing cardiac ischaemia or severe valve dysfunction, severe reduction of ejection fraction, sepsis, DIC, ARD or ESRD not undergoing regularly scheduled dialysis |

ASA V | A moribund person who is not expected to survive without the operation | Examples include (but not limited to): ruptured abdominal/thoracic aneurysm, massive trauma, intracranial bleed with mass effect, ischemic bowel in the face of significant cardiac pathology or multiple organ/systemic dysfunction |

ASA VI | A declared brain-dead person whose organs are being removed for donor purposes |

External Beam Radiation Therapy

External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT) is another option. Its indications parallel those of RP, but will be recommended only when RP is contraindicated or cannot be performed, because it is associated with multiple complications (interstitial radiation: cystitis, proctitis). In conventional EBRT, a total dose of 64 Grays (Gy) is delivered in multiple small fractions of 1.2–2 Gy each. Newer methods have been developed to minimize the side effects of EBRT, allowing higher fractionated and total doses (≥74 Gy) to be given. These include the following:

Intensity modulated radiotherapy IMRT, now considered as the gold standard.

Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy 3D-CRT.

Use of tridimensional conformational technique with intensity modulation (RCMI) permits higher dose and hypofractionating. RCMI allows for the irradiation of larger pelvic volumes including the whole prostate and lymph node (LN) areas without increasing toxicity [20].

Contraindications of EBRT

Absolute contraindications include previous pelvic radiation, Crohn’s disease and active procto-colitis. Relative ones are presence of voiding difficulty and a recent history of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP). It is advised to wait 6–8 weeks after a TURP to minimize the risk of urethral stricture which would be aggravated by EBRT.

Low-Dose Rate Transperineal Brachytherapy

Low-dose rate transperineal brachytherapy (from the Greek word βραχυς, pronounced brachys, which means ‘short’ or ‘brief’): 140 Gy Iodide (125I) or Iridium (192Ir) or 120 Gy Palladium (103Pd) radioisotopes are the most frequently used seeds in permanent interstitial prostatic brachytherapy. Brachytherapy can be considered in patients with a cancer volume ≤50 ml, with less than 50 % of biopsy scores involved with cancer, and an International Prostate Symptom Score (I-PSS) ≤12 (mild to moderate urinary symptoms).

Contraindications of Brachytherapy

A prostate volume >60 ml, the presence of a median lobe, a history of TURP and coexisting voiding difficulty. The presence of a median lobe increases the risk of a postimplantation urinary retention and a history of TURP increases the risk of incontinence [21]. Herein a modified TURP technique was recently proposed for men with moderate lower urinary tract infection (LUTS) prior to brachytherapy, in an attempt to prevent the traditional TURP-related complications [22].

Brachytherapy alone (154 Gy) is recommended for low risk patients, that is, GS 3 + 4 and a PSA <15 ng/ml [23], but not for intermediate risk patients because the probability of biochemical failure is higher than with RP or RT [24]. Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy prior to brachytherapy should not be initiated as it was shown to be associated with an increased risk of overall mortality [25].

The American expert panel has added a further perspective and concluded [26]:

‘AS, interstitial prostate brachytherapy, EBRT, and RP are all appropriate monotherapy options for the low-risk group of patients, and the preference of one to another should be made on an individual patient basis’.

4.1.1.2 Intermediate Risk Patients

cT2b, GS 7 or PSA >10 and ≤20 ng/ml. There is no place here for WW, unless the patient is asymptomatic and unfit for any curative treatment. Also AS is not an option for any GS ≥7 or any PSA ≥10 ng/ml.

The treatment may be RP or EBRT, while brachytherapy and hormonal treatment are possible alternatives for patients unfit for the former treatment options.

In intermediate risk group, the probability of nodal involvement is estimated to be around 10–25 %. It is therefore recommended to perform bilateral pelvic lymphnode dissection (PLND) aiming at clearing the obturator fossa as well as the internal and external iliac lymph nodes (LN) chains [27]. A more extensive PLND (with ≥10 LN removed) has been shown to positively affect the biochemical relapse (BCR)-free survival in patients with intermediate- and high-risk prostate cancers [28]. NVB preservation may be bilateral, but is not recommended when extracapsular extension is suspected (T3a).

A bilateral PLND which should include the ilio-obturators, internal and external iliac groups of LNs up to the bifurcation of the common iliac vessels is recommended in all intermediate and high risk groups. It is optional in low risk group. Frozen section is not recommended anymore [3].

The limits of standard PLND and extended PLND (ePLND) are given in Table 4.2. However, the nomenclature varies according to publishing centres and a more detailed nomenclature was recently proposed including a limited, a standard, an extended and a superextended PLND [29] (Fig. 4.3).

Table 4.2

Anatomical limits of standard PLND and ePLND

Standard PLND | Extended PLND (ePLND) | |

|---|---|---|

Proximal | Common iliac vessels bifurcation | Aortic bifurcation |

Lateral | Genitofemoral nerve | Same |

Medial | Bladder wall | Same |

Distal | Inguinal ligament | Same |

Posterior | Obturator nerve | Hypogastric vessels and pelvic floor |

Fig 4.3

Proposed new nomenclature of pelvic lymph nodes dissection (PLND) [29]: Limited PLND (area 1): posteriorly up to the obturator nerve (corresponds to the classical standard PLND). Standard PLND (areas 1–3): deeper below the obturator nerve onto the internal iliac vessels (corresponds to the classical ePLND). Extended PLND (areas 1–4): proximally up to the aortic bifurcation. Superextended PLND (areas 1–5): deeper to the presacral region. A artery, V vein (By Ploussard et al. European Urology, January 2014; Reproduced and translated with permission from Elsevier)

In intermediate risk patients, EBRT can be given alone with an increased dose (>81Gy) or combined with a short course of hormonal therapy (HT). HT or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) may be started 2 months before EBRT (70 Gy) and continued for a total of 4–6 months. This neoadjuvant and concomitant treatment has been shown to be associated with significantly decreased disease-specific mortality and increased overall survival in the intermediate risk group, as opposed to lower risk group [30]. The benefit of pelvic LN radiation has not been demonstrated [31].

4.1.1.3 High Risk Patients

cT2c or PSA >20 ng/ml or GS >7: As with the intermediate risk group, there is no place for AS. Despite the lack of consensus, a combination therapy may be recommended in high risk patients, and would consist of neoadjuvant hormonal treatment and concomitant hormonal therapy with EBRT. This has been shown to result in an increased overall survival rate which was summarized in a review of several prospective randomized trials [32]. These studies demonstrated that RP + adjuvant HT was associated with a lower cancer-specific mortality compared with EBRT + adjuvant HT [33]. In highly selected patients with T2c, PSA <10 and GS <7, RP or RT alone remains a possible option, however very close posttreatment follow-up is required. Indeed, many researchers have suggested that this tumour is considered as an intermediate risk rather than the traditional high risk tumour based solely on the T2c status [34]. HT may be a first line treatment option for palliation of patients with a short LE and a localized but more extensive or poorly differentiated PC [26].

If controversy and doubt exist about the benefits of neoadjuvant HT prior to EBRT, it is nonetheless generally agreed that there is no place for neoadjuvant HT prior to RP for localized PC whatever the prognostic group [35–39].

The Role of Focal Therapies

These therapeutic options are still under evaluation and it is necessary to inform patients who are offered these treatments about the limited data available for long-term (≥10 years) outcomes [8]. Two modalities are discussed:

High Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU)

This causes tissue damage by thermal effects and cavitation. Temperatures over 65 ° C result in coagulative necrosis. The procedure is performed utilizing transrectal ultrasound (U/S)-guidance under spinal or general anaesthesia. It is frequently preceded by a TURP to prevent the risk of urinary retention induced by the immediate cavitation and flare-up of the prostatic gland provoked by the ultrasound [40].

The qualifying criteria for this treatment are: patients >70 years with LE ≥7 years, T1-T2N0M0, GS ≤7 (3 + 4), PSA ≤15, prostate volume <50 cc and limited tumour volume (less than 4 out of 6 zones involved) [41]. Disease relapse is diagnosed by a PSA value ≥Nadir + 2. Patients with any sign of progression should be considered for salvage radiotherapy.

Note: Nadir is derived from an Arabic word (نظير) which means ‘opposed to’. It was first used in astronomy to refer to the lowest point of a star or a planet in the sky, as opposed to its highest level, the zenith, also from Arabic etymology. It is used here to refer to the lowest level of the PSA in the follow-up after a treatment with curative intent.

Cryotherapy

This is based on the principle of freezing and thawing the prostate in cycles using cryoneedles guided by transrectal ultrasonography. Temperatures of minus 40 ° C are reached under general anaesthesia. The insertion of a urethral warmer is mandatory to avoid thermal injury. The indications include lower and intermediate risks tumours with volume <40 ml. The most commonly encountered complication is erectile dysfunction which occurs in 50–90 % of patients. Other complications include urinary incontinence, bladder neck obstruction, recto-urethral fistulae and perineal pain [42].

4.1.2 Locally Advanced Disease

This includes tumours extending through the prostatic capsule and eventually invading the bladder neck or the seminal vesicles, that is, T3a-b, N0, M0.

(a)

WW remains an option even for T3 patients unfit for local treatment, with a GS <7, and a life expectancy <10 years.

(b)

Combination of RT and HT (or ADT) is now considered as the standard of care for locally advanced PC, as this has shown significant improvement in the 10-year survival compared with either RT or HT alone [43]. In this setting it has been suggested that patients with a lower GS (≤8) could have short-term HT (6 months). However those with a higher GS must be given a long-term HT (preferably ≥ 2 years if tolerated) because of the demonstrated better survival rate [44].

(c)

RT alone is another option as primary treatment for T3 patients when LE is 5–10 years.

(d)

For patients unfit for RT, long-term hormonal treatment alone can be recommended especially for symptomatic T3b patients, with high PSA >25–50, and PSA DT <1 year.

(e)

RP is optional for T3a patients, PSA <20 ng/ml, biopsy Gleason’s score ≤ 8 and LE >10 years, but surgery must be non-nerve preserving with pelvic LN dissection. The patient must be informed about the increased possibility of adjuvant HT in the follow-up because of an increased risk of positive surgical margins (PSM), unfavourable histology and positive lymph nodes in the final histopathology specimen. Similarly adjuvant or salvage EBRT might also be indicated when there are adverse pathological findings in the prostatectomy specimen (seminal vesicles invasion, PSM, or extraprostatic extension). This strategy was credited for the reductions in biochemical recurrences, local recurrence and clinical progression documented in earlier studies [45–47], however the patients should be informed on the uncertain impact of adjuvant EBRT on subsequent metastases and overall survival [48].

As with localized PC, neoadjuvant HT is not indicated prior to RP for locally advanced disease.

4.1.2.1 Modalities of Hormonal Therapy

Complete (or Combined) Androgen Blockade (CAB)

The simplest way to achieve a CAB is by the combination of a bilateral orchiectomy with the use of anti-androgens. Another strategy includes a lutenizing hormone agonist such as leuprolide or goserelin and an androgen-receptor agonist such as flutamide, nilutamide and bicalutamide. The first group of drugs suppresses the secretion of testicular androgens and the second group inhibits the action of circulating androgens on their receptors. Presently CAB is not recommended in locally advanced disease because of very poor survival benefit (<5 %) compared with anti-androgen monotherapy [3].

Bicalutamide (Casodex®) 150-mg Monotherapy

Bicalutamide (Casodex) 150-mg monotherapy has also been shown to have a better posttreatment IIEF-5 score than CAB and could be considered as the treatment for locally advanced prostate cancer in patients concerned by their sexual function [49]. Bicalutamide 150 mg, either as monotherapy or adjuvant therapy to RP or EBRT, has also been shown to improve the progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with locally advanced prostate cancer, but not in patients with localized disease who have demonstrated no clinically or statistically significant improvement and even an unfavourable survival trend compared with WW. Bicalutamide 150 mg also showed benefit in the overall survival (OS) of patients with locally advanced disease as an adjuvant therapy to EBRT [50].

Continued or Intermittent Treatment

The latter aims at improving the side effect profile.

Short or Long

Short or long in combination with EBRT.

Side Effects of Hormonotherapy

Hot flashes, erectile dysfunction and loss of libido, gynaecomastia, cognitive functions impairment and mood disorders, anaemia, fatigue, pseudometabolic syndrome (gain of weight, insulin-resistance), osteopenia. Osteopenia seems to be the most worrisome side effect of hormonotherapy as it may lead to spontaneous fractures. The specific mortality of hip fracture at one year is 37.5 % and this complication alone contributes to an estimated 39-month loss in prostate cancer life expectancy [51].

4.1.3 Disseminated or Metastatic Disease

This is defined by disease extension to pelvic organs (other than seminal vesicles) or wall (i.e. T4), or any N+ or any M+.

Once more, WW is still acceptable for M0 asymptomatic patients, with PSA <50 ng/ml and PSA DT >12 months; however, very close follow-up is required. M+ patients are not suitable for WW.

RP is an option for N+, M0 and ≤T3a patients with LE >10 years. However, RP in this setting must be followed by early adjuvant hormonotherapy [8].

RT indications parallel those of RP, but a combination with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for 3 years is mandatory.

The benefit of adjuvant HT in pN1 patients remains controversial and survival has not been substantiated in a recent study [52].

HT is the standard adjuvant therapy in N+ disease with more than one positive LN, after RP or RT. In M0 disease, HT should not be used as monotherapy for patients fit for surgery or radiotherapy. It is the standard option for M+ disease where there is no place for WW and RP. Here RT can have a palliative option, in combination with androgen deprivation, to alleviate local cancer symptoms.

All patients with M+ disease should be offered bilateral orchidectomy as an alternative to continuous luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist therapy (Goserelin or Zoladex®, leuprorelin and triptorelin). During the initial 1–2 weeks of LHRH-agonist therapy, a biochemical and, sometimes, a clinical ‘flare’ can occur. This may be dangerous especially in presence of vertebral metastases whose flare may compress the spine with neurological consequences. Anti-androgen treatment using cyproterone acetate, diethylstilbestrol, flutamide or nilutamide should be initiated prior to/and concomitant with LHRH-agonist in the first 2 weeks to prevent this adverse event. Ketoconazole is also effective in this setting. LHRH-antagonists (Degarelix) are new drugs reported to cause a more rapid reduction in testosterone levels avoiding the testosterone-induced flare, and to be more effective at maintaining testosterone within castrate levels [53] (Table 4.3).

Table 4.3

Drugs used in hormonotherapy for PC

Surgical castration (the ‘gold standard’) | Bilateral orchidectomy. Subcapsular orchidectomy, also called testicular pulpectomy, has the advantage of leaving behind the tunica albuginea which gives the patient the psychological satisfaction of ‘still having something to palpate in the scrotum’. Replacing the testes by size-matched silicon prostheses can serve the same purpose |

Androgen synthesis inhibitors | Old drugs: Aminogluthetimide, ketoconazole (Nizoral) |

Newer drug: CYP 17 blockers: Abiraterone (Zytiga®) | |

Anti-androgens | These drugs block androgens by competitively binding to their receptors: |

Steroidal: Cyproterone acetate (Androcur) | |

Nonsteoidal: Flutamide (Eulexin®), bicalutamide (Casodex®), nilutamide (Nilandron®). | |

Newer drugs : Enzalutamide (Xtandi®, MDV3100) | |

Inhibitors of LHRH | Lutenizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH)-agonists: Goserelin (Zoladex®), leuprolide (Lupron®, Eligard®), triptorelin (Trelstar®), histrelin (Vantas®) |

LHRH-antagonists: Degarelix (Firmagon®), abarelix, cetrorelix | |

Estrogens | Diethylstilbestrol diphosphate: Fosfetrol (Honvan®) |

Novel drugs have not yet been recommended for primary treatment: Orteronel (TAK-700), galeterone (TOK-700), enzalutamide (MDV3100, Xtandi®) and ARN-509.

One should appreciate that with the general population’s increasing LE, it is commonly recommended to overlook the patient’s chronological age and consider the biological or physiological age which takes into account the patient’s general condition, life style and the presence or absence of comorbidities. The Oncological University Center of Toulouse (IUCT-O) has proposed a theoretical projected estimate of the specific PC mortality which showed that if cardiovascular causes of mortality were delayed in the future, this shift would unmask the PC specific mortality. In other words, it implies that in future many patients will qualify for active PC treatment at an age presently considered as being too old. Conversely, the delay in PC mortality would increase deaths from other causes, deepening the masking effect on the PC specific mortality. This is referred to as ‘competitive mortality theory’ (Fig. 4.4a–c).

Fig. 4.4

(a–c) Competitive mortality theory between death from PC and other diseases. (a) Mortality from prostate is in competition with mortality from other causes. Therefore the specific mortality from PC is the result of various evolutions. (b) Decrease in mortality from cardio-vascular may “unmask” the specific mortality from PC, causing the latter to increase. (c) Conversely a delay in the mortality from PC may deepen the masking effect through increased mortality from other causes (a–c: By P. Grosclaude, Tarn Cancers Registry, IUCT-O, Toulouse, F-31059, France. Reproduced and translated with permission)

Take-Home Message: Role of the Various Primary Treatment Modalities in PC

Watchful waiting | Standard in T1a with GS <7, LE <10 |

Optional in asymptomatic T3 GS <7, LE <10 years unfit for local treatment | |

Optional asymptomatic M0, N+ with PSA <50 ng/ml, PSA DT >12 months (very close follow-up) | |

Active surveillance | This requires a regular follow-up of the patient with repeat PSA every 3–6 months for PSADT calculation, DRE every 6–12 months and TRUS-guided biopsy between 3 and 18 after the first set to rule out undergrading of the tumour |

All T1a when LE >10 | |

T1b-T2b with PSA <10, GS <7, ≤2 positive biopsies and ≤50 % cancer in each biopsy, patients LE <10 years, patients LE >10 years (informed about lack of survival data beyond 10 years), patients refusing treatment-related complications | |

Radical prostatectomy | Standard treatment for organ-confined disease (T1a-T2c) with LE >10. Best indication for T1a when GS ≥7 |

Optional for T3a patients with PSA <20, GS ≤8 and LE >10. Increased risk of PSM, positive LN and unfavourable histology. Hence adjuvant RT or HT possibly needed | |

Optional for N+ patients < T4 and LE >10 years, combined with adjuvant RT or HT | |

No place in M+ patients | |

External beam radiation therapy | T1a in younger patients with long LE and GS >7. |

All organ-confined disease (T1c–T2c) with LE >10 unfit for surgery and accepting related complications. Unfit patients with LE 5–10 and GS >7 (combined with adjuvant HT | |

T3 with LE >5–10 years. Escalating dose and adjuvant HT < div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|