Background

In the Western world, transitional cell carcinoma (TCC) of the bladder represents the fourth most frequently diagnosed malignancy. In 2008, an estimated 68,810 new incidences of TCC of the bladder will be diagnosed in the US [1]. Of the patients newly diagnosed with bladder cancer, approximately 75–85% present with a nonmuscle-invasive (superficial) tumor. A wide range of recurrence and progression rates has been reported among patients with bladder cancer, and these rates depend largely on the number of tumors initially identified, tumor size, prior recurrence rate, T category, grade and concomitant carcinoma in situ (CIS). According to data from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), the probability of recurrence 5 years after the initial diagnosis is 31–78%, and the probability of progression at 5 years is < 1–45% [2]. These high recurrence and progression rates necessitate long-term surveillance and various adjuvant therapeutic strategies in patients with bladder cancer.

Depending on the estimated aggressiveness of the disease, therapeutic options range from a single transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) with early post transurethral resection (TUR) instillation therapy over TURBT followed by multiple cycles of intravesical chemo- or immunotherapy (bacille Calmette–Guerin: BCG) to radical cystectomy.

The aim of the initial TURBT or biopsy is to obtain tissue for the correct diagnosis and to remove all visible lesions. The resection strategy depends on the size and number of the lesions. A complete and correct TUR has been reported to be essential for optimizing response [3].

Generally, after TURBT of nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer, one immediate postoperative instillation of chemotherapy is recommended. The need for further adjuvant intravesical therapy depends on the calculated aggressiveness of the detected tumor. Different chemotherapeutic agents are used in a variety of application schedules. BCG as intravesical immunotherapy has shown the ability to reduce recurrence and even progression rates in high-grade superficial tumors. Finally, there is the option of immediate cystectomy in those patients who present with nonmuscle-invasive tumor but may have a high risk of progression based on pathological features. Reported indicators for a higher risk of progression are multiple recurrent high-grade tumors, high-grade T1 tumors, and high-grade tumors with concomitant CIS. In such patients, a delayed cystectomy could lead to decreased disease-specific survival [4].

Clinical question 31.1

What is the benefit from a single immediate postoperative intravesical instillation of a chemotherapeutic agent?

Literature search

We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized trials and observational studies in the Cochrane Library (2008) and Medline (1966–Jan 2009) using the search terms: “bladder cancer,” “instillation therapy,” “early intra-vesical chemotherapy,” “immediate instillation,” “early instillation,” “urothelial carcinoma.”

The evidence

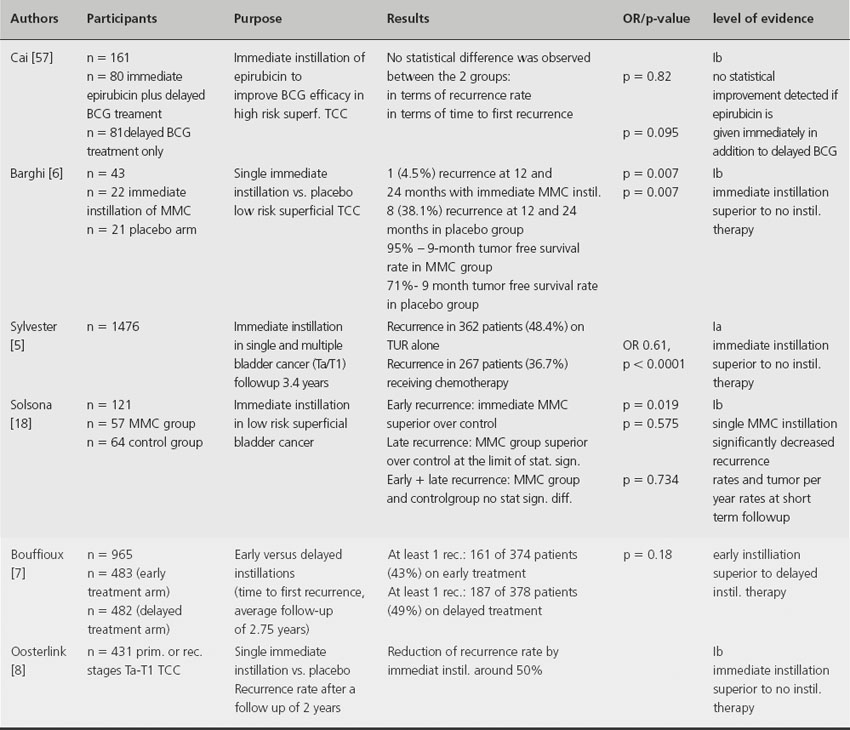

A meta-analysis of seven randomized trials involving 1476 patients with a median follow-up of 3.4 years found that one immediate instillation of chemotherapy within 6–24 hours post TURBT has the ability to decrease the recurrence rate by 12% and the odds of recurrence by 39% [5]. Other studies demonstrate that immediate chemo-instillation after TURBT reduces the risk of recurrence by about 50% at 2 years and ≥ 15% at 5 years [6–9]. Mitomycin C, epirubicin and doxorubicin have been shown to be comparably beneficial [5]. Another randomized prospective study demonstrates that a delayed instillation therapy (between 7 and 15 days after the initial resection) is associated with a significantly higher recurrence rate compared to an immediate instillation therapy if no maintenance therapy is applied [7] (see Table 31.1). Immediate instillation therapy has no reported influence on the progression rate or overall survival of patients with superficial bladder cancer.

Table 31.1 Immediate postoperative intravesical instillation of a chemotherapeutic agent

Comment

The presented studies indicate that a single intravesical instillation of chemotherapy immediately following TURBT (< 24 hours) significantly decreases the risk of recurrence in patients with nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. Therefore it should be administered to all patients following TURBT of presumably nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. No single chemotherapeutic drug has been shown to be superior. In terms of the optimal timing for immediate instillation therapy, a meta-analysis could not detect significant differences in efficacy as long as the instillation is given within 24 hours; however, instillation in the first 6 hours seems preferable [5].

In general, one immediate instillation is considered to be safe, as long as there is no evident bladder perforation or known allergies to the applied substance. Known prior reaction to an intravesically instilled chemotherapeutic agent should be considered a relative contraindication to such instillation with a different agent (Grade 1B).

Clinical question 31.2

BCG treatment – is maintenance therapy the standard of care?

Literature search

We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized trials and observational studies in the Cochrane Library (2008) and Medline (1966–Jan 2009) using the search terms: “bladder cancer,” “urothelial carcinoma,” “BCG,” “bacille Calmette–Guerin,” “intravescial therapy,” “maintenance.”

The evidence

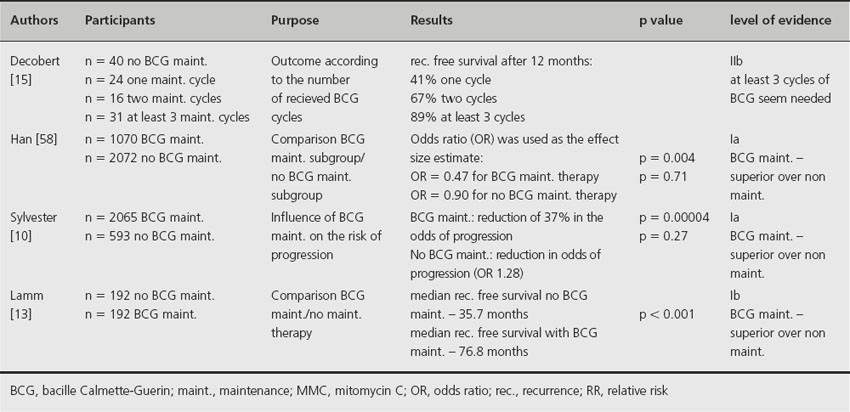

Based on meta-analysis of published data involving 2658 patients from 24 trials, maintenance intravesical BCG therapy appears to reduce recurrence and progression rates [10]. In this meta-analysis, four trials were analyzed in which no maintenance therapy was given. In these cases no reduction in progression (p = 0.27) was observed. In the other 20 trials that used some form of BCG maintenance therapy, a reduction of 37% in the odds of progression was demonstrated (p = 0.00004). However, at least 1 year of maintenance BCG therapy was required to demonstrate its superiority in preventing recurrence or progression [11]. In a second meta-analysis involving nine clinical trials, only those patients receiving BCG maintenance demonstrated statistically significant reduction in tumor progression compared to mitomycin C (MMC) (p = 0.02) [12]. Lamm et al. conducted a prospective multicenter study that also supports the concept of maintenance BCG therapy [13]. The median recurrence-free survival was found to be 35.7 months in the group not receiving any maintenance therapy compared to 76.8 months in the group receiving maintenance therapy (p < 0.001). Based on current literature, the optimal maintenance BCG regimen is still unclear due to lack of data.

Comment

Based on the presented studies, maintenance intravesical instillation of BCG is associated with reduced risk of recurrence and progression from nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer [10–12,13,14] and should be regarded as the standard of care. Although a variety of different maintenance regimens have reported efficacy, the optimal regimen is still unclear. Based on data from one randomized trial [13], the regimen commonly used has been induction BCG instillations once a week for 6 weeks. Additional 3-weekly instillations are performed 12 weeks following the first BCG instillation as long as there is no evidence of disease recurrence. Additional 3-weekly instillations are performed at 6-monthly intervals thereafter for a total of 2–3 years. According to Decobert et al., at least three cycles of BCG seem to be needed to achieve optimum results [15]. It has to be taken into account that BCG maintenance therapy may be associated with an increased risk of side effects, which was reflected by the relatively low percentage of patients who completed all recommended BCG cycles in the largest randomized trial of BCG maintenance therapy [13] (see Table 31.2). In general, more adverse reactions are reported in BCG-treated patients than in MMC-treated patients. The possible risk of BCG treatment should be balanced for every patient individually (Grade 2B).

Table 31.2 BCG maintenance therapy

Clinical question 31.3

What treatment is recommended for BCG-refractory nonmuscle-invasive TCC?

Literature search

We searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized trials and observational studies in the Cochrane Library (2008) and Medline (1966–Jan 2009) using the search terms: “bladder cancer,” “urothelial carcinoma,” “BCG refractory,” “BCG failure,” “bacille Calmette–Guerin,” “BCG long term,” “treatment.”

The evidence

Definition of a BCG failure

A BCG treatment is considered to have failed either if a tumor progresses to a muscle-invasive stage or if a tumor of higher grade and/or stage, even if nonmuscle invasive, is identified at either 3 or 6 months after initiation of induction BCG instillation therapy [16].

According to Herr & Dalbagni, a BCG failure should not be declared until after at least 6 months of BCG therapy [16]. In patients with tumor detected at 3 months, an additional course of BCG for 6 weeks has yielded a complete response in more than 50% of patients with papillary tumors and CIS [16,17]. On the other hand, Solsona et al. suggest that presence of tumor at the first cystoscopy following completion of induction BCG therapy for 6 weeks, i.e. at 3 months after commencement of instillation of BCG, indicates lack of response and a significantly worse outcome [18]. Lerner et al. found that a failure to achieve a complete response after BCG induction therapy is associated with a significant risk of a worsening event and death for patients with CIS or Ta–T1 bladder cancer [19].

The EAU guidelines strongly advocate immediate cystectomy upon BCG failure, because of the high risk of development of muscle-invasive tumor in these patients.

Alternative approaches such as the use of BCG plus interferon in patients with BCG failure have been shown to be effective in phase II studies, with 44–59% recurrence-free survival at 2 years [20,21].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree