Introduction

Over the past 20–30 years, the premature ejaculation (PE) treatment paradigm, previously limited to behavioral psychotherapy, has expanded to include drug treatment [1,2]. Animal and human sexual psychopharmacological studies have demonstrated that serotonin and 5-HT receptors are involved in ejaculation and confirm a role for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in the treatment of PE [3–6]. Many well-controlled evidence-based studies have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of SSRIs in delaying ejaculation, confirming their role as first-line agents for the treatment of lifelong and acquired PE [7]. More recently, there has been increased interest in the psychosocial consequences of PE, its epidemiology, its etiology and its pathophysiology from both clinicians and the pharmaceutical industry [8–13].

Clinical question 14.1

What is the definition of premature ejaculation?

The evidence

Medline, Web of Science, PsychINFO, EMBASE and the proceedings of major international and regional scientific meetings were searched for publications or abstracts using the words in the title, abstract or keywords “premature ejaculation,” “rapid ejaculation,” “ejaculation,” “definition,” “control,” “distress,” “sexual satisfaction,” “ejaculatory latency.” This search was then manually cross-referenced for all papers.

The medical literature contains several univariate and multivariate operational definitions of PE [2,14–21]. Each of these definitions characterizes men with PE using all or most of the accepted dimensions of this condition: ejaculatory latency, perceived ability to control ejaculation, and negative psychological consequences of PE including reduced sexual satisfaction, personal distress, partner distress and interpersonal or relationship distress.

The first official definition of PE was proposed in 1980 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) [22]. This definition was progressively revised in the DSM-III-R, DSM-IV and finally DSM-IV-TR to include “shortly after penetration” as an ejaculatory latency criterion, “before the person wishes it” as a control criterion and “causes marked distress or interpersonal difficulty” as a criterion for the negative psychological consequences of PE [14,23,24]. Although DSM-IV-TR, the most commonly quoted definition, and other definitions of PE differ substantially, they are all authority based, i.e. expert opinion without explicit critical appraisal, rather than evidence based, and have no support from controlled clinical and/or epidemiological studies [25]. The DSM definitions are primarily conceptual in nature, vague in terms of operational specificity, multi-interpretable, fail to provide any diagnostic intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT) cut-off points and rely on the subjective interpretation of these concepts by the clinician [26–28]. The absence of a clear IELT cut-off point in the DSM definitions has resulted in the use of a broad range of subjective latencies for the diagnosis of PE in clinical trials ranging from 1 to 7 minutes [29–37]. The failure of DSM definitions to specify an IELT cut-off point means that a patient in the control group of one study may very well be in the PE group of a second study, making comparison of studies difficult and generalization of their data to the general PE population impossible.

This potential for errors in the diagnosis of PE was demonstrated in two recent observational studies in which PE was diagnosed solely by the application of the DSM-IV-TR definition [11,38]. Giuliano et al. diagnosed PE using DSM-IV-TR criteria in 201 of 1115 subjects (18%) and predictably reported that the mean and median IELT were lower in subjects diagnosed with PE compared to non-PE subjects. There was, however, substantial overlap in stopwatch IELT values between the two groups. In subjects diagnosed with PE, the IELT range extended from 0 seconds (antiportal ejaculation) to almost 28 minutes with 48% of subjects having an IELT in excess of 2 minutes and 25% of subjects exceeding 4 minutes. This study demonstrates that a subject diagnosed as having PE on the basis of DSM-IV-TR criteria has a 48% risk of not having PE if a PE diagnostic threshold IELT of 2 minutes, as suggested by community-based normative IELT trial, is used [10].

The first contemporary multivariate evidence-based definition of lifelong PE was developed in 2008 by a panel of international experts, convened by the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM), who agreed that the diagnostic criteria necessary to define PE are: time from penetration to ejaculation, inability to delay ejaculation and negative personal consequences from PE. This panel defined lifelong PE as a male sexual dysfunction characterized by “. . . ejaculation which always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about one minute of vaginal penetration, the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations, and the presence of negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy” [39].

This definition is supported by evidence from several controlled clinical trials.

Evidence to support inclusion of the criterion of “. . . ejaculation which always or nearly always occurs prior to or within about one minute of vaginal penetration . . .”

Operationalization of PE using the length of time between penetration and ejaculation, the IELT, forms the basis of most current clinical studies on PE [40]. IELT can be measured by a stopwatch or estimated. Several authors report that estimated and stopwatch IELT correlate reasonably well or are interchangeable in assigning PE status when estimated IELT is combined with patient-reported outcomes (PROs) [41–43].

Several studies suggest that 80–90% of men seeking treatment for lifelong PE ejaculate within 1 minute (Table 14.1) [44–46]. Waldinger et al. reported IELTs < 30 s in 77% and < 60 s in 90% of 110 men with lifelong PE, with only 10% ejaculating between 1 and 2 minutes. These data are consistent with normative community IELT data, support the notion that IELTs of less than 1 minute are statistically abnormal and confirm that an IELT cut-off of 1 minute will capture 80–90% of treatment-seeking men with lifelong PE [10]. Further qualification of this cut-off to “about 1 minute” affords the clinician sufficient flexibility to also diagnose PE in the 10–20% of PE treatment-seeking men who ejaculate within 1–2 minutes of penetration without unnecessarily stigmatizing the remaining 80–90% of men who ejaculate within 1–2 minutes of penetration but have no complaints of PE.

Table 14.1 Findings of key publications regarding the time-to-ejaculate in PE

| Author/s | Summary of primary findings |

| Waldinger et al. [44] | 110 men with lifelong PE whose IELT was measured by the use of a stopwatch |

| 40% of men ejaculated within 15 seconds, 70% within 30 seconds, and 90% within 1 minute | |

| McMahon [45] | 1346 consecutive men with PE whose IELT was measured by the use of a stopwatch/wristwatch 77% of men ejaculated within 1 minute |

| Waldinger et al. [46] | 88 men with lifelong PE who self-estimated IELT 30% of men ejaculated within 15 seconds, 67% within 30 seconds, and 92% within 1 minute after penetration Only 5% ejaculated between 1 and 2 minutes |

| Waldinger et al. [10] | Stopwatch IELT study in a random unselected group of 491 men in 5 countries |

| IELT had a positive skewed distribution | |

| Application of 0.5 and 2.5 percentiles as disease standards 0.5 percentile equated to an IELT of 0.9 min and 2.5 percentile to an IELT of 1.3 min | |

| Althof [41] | IELT estimations for PE men correlate reasonably well with stopwatch-recorded IELT |

| Pryor et al. [42] | IELT estimations for PE men correlate reasonably well with stopwatch-recorded IELT |

| Rosen et al. [43] | Self-estimated and stopwatch IELT as interchangeable Combining self-estimated IELT and PROs reliably predicts PE |

Evidence to support inclusion of the criterion “. . . the inability to delay ejaculation on all or nearly all vaginal penetrations . . .”

The ability to prolong sexual intercourse by delaying ejaculation and the subjective feelings of ejaculatory control comprise the complex construct of ejaculatory control. Virtually all men report using at least one cognitive or behavioral technique to prolong intercourse and delay ejaculation, with varying degrees of success, and many young men reported using multiple different techniques [47]. Voluntary delay of ejaculation is most likely exerted either prior to or in the early stages of the emission phase of the reflex but progressively decreases until the point of ejaculatory inevitability [48,49].

Several authors have suggested that an inability to voluntarily defer ejaculation defines PE (Table 14.2) [50–53]. Patrick et al. reported ratings of “very poor” or “poor” for control over ejaculation in 72% of men with PE compared to 5% in a group of normal controls [11]. Lower ratings for control over ejaculation were associated with shorter IELT with “poor” or “very poor” control reported by 67.7%, 10.2% and 6.7% of subjects with IELT < 1 min, > 1 min and > 2 min respectively.

Table 14.2 Findings of key publications regarding ejaculatory control in PE

| Author/s | Summary of primary findings |

| Grenier & Byers [47] | Relatively weak correlation between ejaculatory latency and ejaculatory control (R = 0.31) |

| Ejaculatory control and latency are distinct concepts | |

| Grenier & Byers [54] | Relatively poor correlation between ejaculatory latency and ejaculatory control, sharing only 12% of their variance suggesting that these PROs are relatively independent |

| Waldinger et al. [44] | Little or no control over ejaculation was reported by 98% of subjects during intercourse |

| Weak correlation between ejaculatory control and stopwatch IELT (p = 0.06) | |

| Rowland et al. [56] | High correlation between measures of ejaculatory latency and control (R = 0.81, p < 0.001) |

| Patrick et al. [11] | Men diagnosed with PE had significantly lower mean ratings of control over ejaculation (p < 0.0001) 72% of men with PE reporting ratings of “very poor” or “poor” for control over ejaculation compared to 5% in a group of normal controls |

| IELT was strongly positively correlated with control over ejaculation for subjects (R = 0.51) | |

| Giuliano et al. [57] | Men diagnosed with PE had significantly lower mean ratings of control over ejaculation (p < 0.0001) “Good” or “very good” control over ejaculation in only 13.2% of PE subjects compared to 78.4% of non-PE subjects Perceived control over ejaculation had a significant effect on intercourse satisfaction and personal distress |

| IELT did not have a direct effect on intercourse satisfaction and had only a small direct effect on personal distress | |

| Patrick et al. [58] | Effect of IELT upon satisfaction and distress appears to be mediated via its direct effect upon control |

| Rosen et al. [43] | Control over ejaculation and subject assessed level of personal distress are more influential in determining PE status than IELT |

| Subject reporting “very good” or “good” control over ejaculation is 90.6% less likely to have PE than a subject reporting “poor” or “very poor” control over ejaculation |

However, control is a subjective measure which is difficult to translate into quantifiable terms and is the most inconsistent dimension of PE. Control has yet to be adequately operationalized to allow comparison across subjects or across studies. Grenier & Byers failed to demonstrate a strong correlation between ejaculatory latency and subjective ejaculatory control [47,54]. Several authors report that diminished control is not exclusive to men with PE and that some men with a brief IELT report adequate ejaculatory control and vice versa, suggesting that the dimensions of ejaculatory control and latency are distinct concepts [11,47,55]. Furthermore, there is a higher variability in changes in control compared to IELT in men treated with SSRIs [7].

Contrary to this, several authors have reported a moderate correlation between the IELT and the feeling of ejaculatory control [11,43,56,57]. Rosen et al. report that control over ejaculation, personal distress and partner distress was more influential in determining PE status than IELT [43]. In addition, the effect of IELT upon satisfaction and distress appears to be mediated via its direct effect upon control [58].

However, despite conflicting data on the relationship between control and latency, the balance of evidence supports the notion that the inability to delay ejaculation appears to differentiate men with PE from men without PE [11,57,59].

Evidence to support exclusion of the criterion of sexual satisfaction

Men with PE report lower levels of sexual satisfaction compared to men with normal ejaculatory latency. Patrick et al. reported ratings of “very poor” or “poor” for sexual satisfaction in 31% of subjects with PE compared to 1% in a group of normal controls [11].

However, caution should be exercised in assigning lower levels of sexual satisfaction solely to the effect of PE and contributions from other difficult-to-quantify issues such reduced intimacy, dysfunctional relationships, poor sexual attraction, and poor communication should not be ignored. This is supported by the report of Patrick et al. that despite reduced ratings for satisfaction with shorter IELTs, a substantial proportion of men with an IELT < 1 min report “good” or very good” satisfaction ratings (43.7%).

The current data are limited but suggest that sexual satisfaction is of limited use in differentiating PE subjects from non-PE subjects and are not included in the ISSM definition of PE [11].

Evidence to support inclusion of the criterion “. . . the presence of negative personal consequences, such as distress, bother, frustration and/or the avoidance of sexual intimacy”

Premature ejaculation has been associated with negative psychological outcomes in men and their women partners (Table 14.3) [9,11,12,57,59–69]. Patrick et al. reported significant differences in men with and without PE in the PRO measures of personal distress (64% versus 4%) and interpersonal difficulty (31% versus 1%), suggesting that this personal distress has discriminative validity in diagnosing men with and without PE.

Table 14.3 Findings of key publications regarding the negative personal consequences of PE

| Author/s | Summary of primary findings |

| Patrick et al. [11] | Using the validated Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP), 64% of men in the PE group versus 4% in the non-PE group reported personal distress |

| Giuliano et al. [57] | On the PEP 44% of men in the PE group versus 1% of men in non-PE group reported personal distress |

| Rowland et al. [61] | Men in highly probable PE group reported greater distress versus men in non-PE group on PEP scale On the Self Esteem and Relationship Questionnaire (SEAR) men with highly probable PE had lower mean scores overall, for confidence and self-esteem versus non-PE men |

| Rowland et al. [59] | 30.7% of probable PE group, 16.4% of possible PE group vs 7.7% of non-PE group found it difficult to relax and not be anxious about intercourse |

| Porst et al. [12] | Depression reported by 20.4% of PE group vs 12.4% of non-PE group Excessive stress in 28% of PE group vs 19% of non-PE group Anxiety in 24% of PE group vs 13% in non-PE group |

| McCabe. [63] | Sexually dysfunctional men, including those with PE, scored lower than sexually functional men on all measures of intimacy on the Psychological and Interpersonal Relationship Scale (PAIRS) |

| Symonds et al. [9] | 68% reported self-esteem affected by PE. Decreased confidence in sexual encounter Anxiety reported by 36% (causing PE or because of it) Embarrassment and depression also cited due to PE |

| Dunn et al. [60] | Strong association of PE with anxiety and depression on the Hospital and Anxiety Scale |

| Hartmann et al. [66] | 58% of PE group reported partner’s behavior and reaction to PE was positive and 23% reported it was negative |

| Byers et al. 2003 [64] | Men with PE and their partners reported slightly negative impact of PE on personal functioning and sexual relationship but no negative impact on overall relationship |

The personal and/or interpersonal distress, bother, frustration and annoyance that result from PE may affect men’s quality of life and partner relationships, their self-esteem and self-confidence, and can act as an obstacle to single men forming new partner relationships [9,11,12,57,59–69]. McCabe reported that sexually dysfunctional men, including men with PE, scored lower on all aspects of intimacy (emotional, social, sexual, recreational and intellectual) and had lower levels of satisfaction compared to sexually functional men (p < 0.001 or p < 0.01) [63]. Rowland et al. showed that men with PE had significantly lower overall health-related quality of life, total Self-Esteem and Relationship Questionnaire (SEAR) scores and lower confidence and self-esteem compared to non-PE groups [61]. PE men rated their overall health-related quality of life lower than men without PE (p ≤ 0.001).

This definition should form the basis for the office diagnosis of lifelong PE. It is limited to heterosexual men engaging in vaginal intercourse as there are few studies available on PE research in homosexual men or during other forms of sexual expression. The panel concluded that there is insufficient published evidence to propose an evidence-based definition of acquired PE [39]. However, recent unpublished data suggest that men with acquired PE have similar IELTs and report similar levels of ejaculatory control and distress, suggesting the possibility of a single unifying definition of PE.

Comment

The evidence suggests that the multivariate evidence-based ISSM definition of lifelong PE gives the clinician a more discriminating diagnostic tool. The IELT cut-off of about 1 minute captures the 90% of men with PE who actively seek treatment and ejaculate within 1 minute but also affords the clinician sufficient flexibility to also diagnose PE in the 10% of PE treatment-seeking men who ejaculate within 1–2 minutes of penetration. If the ISSM definition is used, men who ejaculate in < 1 minute but report adequate control and no personal negative consequences related to their rapid ejaculation do not merit the diagnosis of PE. Similarly, men who have IELTs of 10 minutes but report poor control, dissatisfaction and personal negative consequences also fail to meet the criteria for PE.

Clinical question 14.2

Is psychosexual cognitive behavioral therapy effective as a treatment for premature ejaculation?

The evidence

Medline, Web of Science, PsychINFO, EMBASE and the proceedings of major international and regional scientific meetings were searched for publications or abstracts using the words in the title, abstract or keywords “premature ejaculation,” “rapid ejaculation,” “ejaculation,” “cognitive behavioral therapy,” “psychological counseling” and “sex therapy.” This search was then manually cross-referenced for all papers.

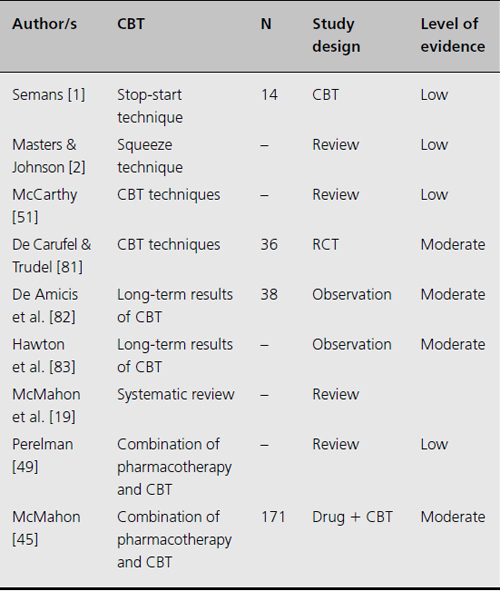

The cornerstones of cognitive behavioral treatment (CBT), the Semans “stop-start” maneuver and the Masters & Johnson “squeeze technique,” were first described as a treatment of PE more than 50 years ago [1,2]. Although contemporary psychotherapy research has attempted to adapt the methodology of clinical psychopharmacology randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to define empirically supported psychotherapies [70,71], the medical literature is characterized by an almost complete lack of supportive RCTs (Table 14.4). Rowland & Burek reported a trend over the past 25 years towards the publication of biological and pharmacological articles and a decline in the proportion of psychological behavior articles [72]. They suggested that researchers are missing the opportunity to investigate important biobehavioral interactions underlying ejaculatory dysfunction, and to augment the current biopharmacological paradigm by integrating cognitive behavioral and sex therapy programs into pharmacological PE treatment

Table 14.4 Findings of key publications regarding cognitive behavioral therapy/psychotherapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree