Introduction

The annual number of patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has increased in the last decade, due in part to an increase in incidentally found tumors, but studies suggest that this increase is not due to lead time bias alone [1]. This increasing incidence of RCC has occurred across all clinical stages, but the highest increase has been observed for the incidence of localized tumors, with an average annual increase of 3.7% between 1973 to 1998 based on the SEER database [2,3]. Similarly, the incidental detection of RCC has increased, being 7% in a series from 1935 to 1965, whereas it increased to 61% in a series from 1998 [4,5].

Since the outcome of patients surgically treated for localized RCC of less than 4 cm is very good (96% 5-year disease-free survival), the management of localized RCC has more recently also focused on outcomes other than just oncological ones [6]. Of those, the perioperative outcomes and renal functional outcomes have been studied to optimize the treatment of localized RCC. Furthermore, new management strategies such as laparoscopy, cryotherapy, radiofrequency and active surveillance have emerged in the last two decades with the common goal of providing better quality of life and functional outcomes while preserving oncological success associated with more radical techniques. The interest in studying oncological outcomes together with perioperative and renal function outcomes has led to a substantial number of good-quality publications that can allow us to give recommendations on various aspects of the treatment of localized RCC. From a surgical standpoint, the role of partial nephrectomy, laparoscopic radical nephrectomy and lymph node dissection has been studied sufficiently to allow us to provide recommendations using the Grade level of evidence.

Comparing open and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy

Background

Radical nephrectomy (RN) is indicated for the treatment of renal tumors suspicious for RCC with the goal of surgically curing the patient and preventing metastasis. Traditionally, RN includes the en bloc removal of the tumor, kidney, adrenal, perirenal fat and Gerota’s fascia, which can be done through many surgical approaches. Most approaches have been developed for open radical nephrectomy (ORN). Depending on the tumor location, size and invasion of the venous system, thoracoabdominal, transabdominal, flank or lumbotomy approaches have been described. These can be performed by both transperitoneal or extraperitoneal approaches.

In the last 20 years, however, laparoscopic surgery has emerged as an alternative to the open approach in urology. The first laparoscopic radical nephrectomy (LRN) was described by Clayman et al. in 1991 [7]. Since then, techniques and approaches of LRN have evolved, and this technique is now widely used in urological practice. One of these further evolutions is the use of a hand-port that allows surgeons to assist laparoscopic manipulation with one hand in the patient without compromising the pneumoperitoneum. This technique has been named hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy (HALN). Like RN, laparoscopic nephrectomy can also be performed by the transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approaches. Several postulated advantages of laparoscopic surgeries include reduction in the length of hospital stay, less requirement for opioid pain relief, faster recuperation, and better cosmetic results. Opponents of LRN initially raised questions regarding the risk of trauma to intra-abdominal organs, the inability to palpate intra-abdominal organs and lymph nodes, and the inability to perform adequate lymph node dissection (LND). During the same period, simple laparoscopic nephrectomy (LN) has also been developed for living donor nephrectomy, which has allowed prospective randomized study to compare open nephrectomy (ON) and laparoscopic approaches for perioperative morbidity [8–11]. Many of these studies are now published, and a meta-analysis is available [12].

In this section, we will summarize the literature regarding two questions related to radical nephrectomy approaches. What are the differences in perioperative outcomes between open and laparoscopic nephrectomy? What are the differences in oncological outcomes between open and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy?

Clinical question 34.1

What is the role of laparoscopic nephrectomy in the management of RCC?

Literature search

Potentially relevant studies were identified by a search of the Medline electronic database (source PubMed, 1966 to December 2008) using relevant keywords in combination, as follows: nephrectomy AND laparoscopy AND open (163 articles retrieved) OR nephrectomy AND laparoscopy AND open AND review (24 articles retrieved). Original AND review articles were selected based on language (English only) and revelance of their title. A total of 112 articles were kept for abstract analysis.

We have included in our analysis studies performed to analyze differences between ORN and LRN for RCC. Prospective and retrospective studies were included. Studies including nephroureterectomy, nephrectomy for known benign lesions, and noncontemporary comparisons between ORN and LRN were excluded. When two studies were from the same cohort and/or center, only the most recent update was included. Since relatively few studies were randomized and/or prospective, we extended our analysis to randomized prospective studies that were done in the context of living donor nephrectomy and that have compared open and laparoscopic approaches to study the perioperative outcomes or the two approaches. We also included the results of a recent meta-analysis that combined all the studies comparing the perioperative outcomes of open and laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy.

The evidence

Perioperative outcomes

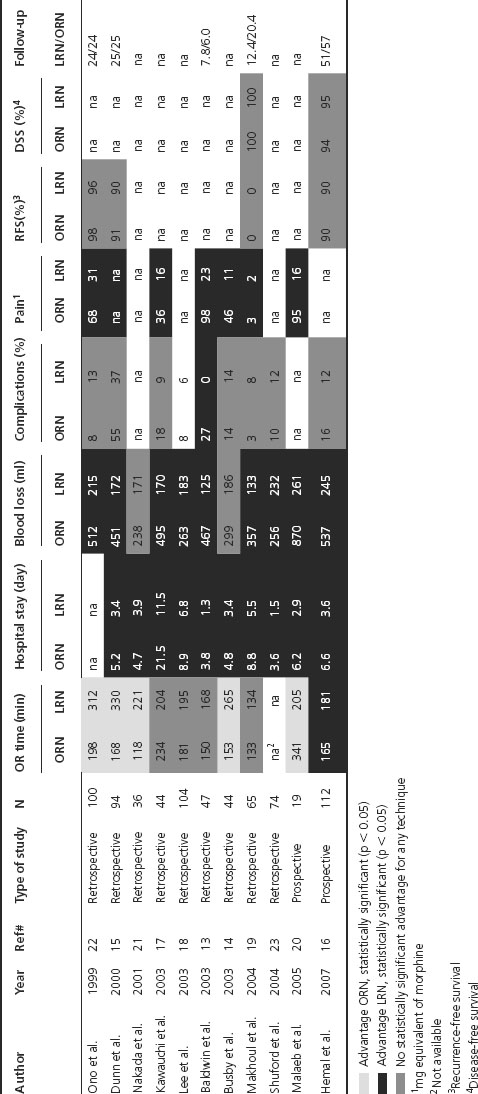

We identified two prospective, nonrandomized studies and nine retrospective studies that addressed perioperative outcomes after radical nephrectomy for RCC (Table 34.1) [13–23]. Five of the 11 studies compared HALN with ORN. The perioperative factors that were reviewed included: operative time, blood loss, transfusions, complications, morphine equivalent requirements and hospital stay. Regarding operating room (OR) time, one prospective and four retrospective studies reported statistically significantly (SS) less OR time for ORN. Three studies reported less, but not SS less, OR time for ORN. Two other studies reported a SS increased OR time with ORN, but those two studies had extraordinary long ORN OR time when compared to other series [17,20]. Average OR time among studies was 166 minutes for ORN and 223 minutes for LRN (excluding the Malaeb and Kawauchi studies). Blood loss was consistently less with the LRN approach in all studies. Only two out of the 11 studies did not show a SS difference [14,21]. Average blood loss was 431 mL for ORN and 190 mL for LRN. Similarly, transfusion rates were 0–20% for the RN. Two out of four studies reported SS more, one less, and one no difference in the transfusion rate with ORN. Complication rates where similar when comparing the two approaches (range was 3–55% for ORN and 0–37% for LRN). Only one retrospective study reported SS fewer complications with LRN [13]. Pain, which is reflected by consumption of morphine equivalents, was SS less in all the LRN studies that looked at this outcome. Finally, average hospital stay was 3.6 days for LRN and 5.8 days for ORN (excluding the Kawauchi study which had an extraordinarily long hospital stay that might reflect surgeon preference rather than the effect of surgery). Of note, three studies have also shown than LRN was associated with a shorter time to return to normal activities [14,21,22].

Table 34.1 Studies comparing perioperative and oncological outcomes between open (ORN) and laparoscopic radical nephrectomy (LRN)

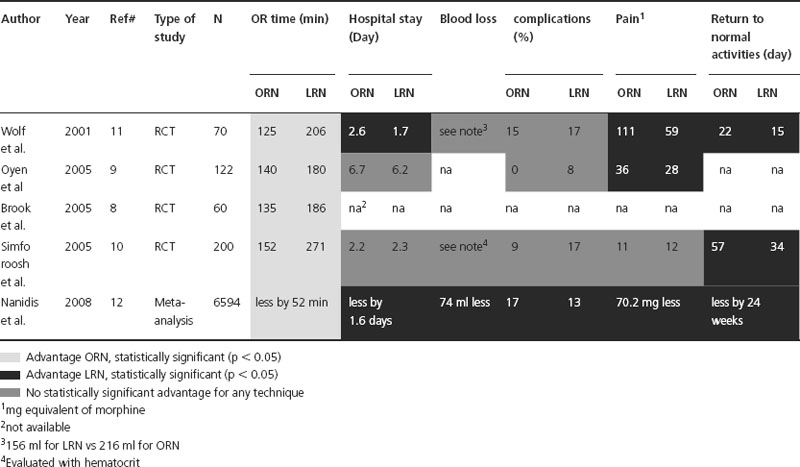

Since no randomized controlled trial (RCT) was available to assess perioperative outcomes to compare ON and LN, we included in our analysis four RCTs that were published in the living donor kidney transplant literature (Table 34.2) [8–11]. A fifth study by Oyen et al. was not included since the same group published their updated results in 2005 [9,24]. Regarding OR time, all the RCTs showed that LN was SS longer than ON. In the two studies that assessed blood loss, no SS difference was observed. Only one study statistically analyzed the complications, and no difference was observed between the two techniques [11]. Pain assessed by morphine equivalent was higher in the ON group in two of the three studies that reported statistics on this outcome. Finally, hospital stay was not SS different in two RCTs while SS less for LN in one study. Of note, the Oyen study had a prolonged hospital stay with an average of more than 6 days for both techniques.

Table 34.2 Randomized controlled studies comparing perioperative outcomes between open (ON) and laparoscopic nephrectomy (LN) for living donor transplant

In a meta-analysis, Nanidis et al. analyzed all the published studies comparing open and laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy [12]. A total of 6594 patients were included from 73 studies. Overall, the meta-analysis revealed that ON was associated with less OR and warm ischemia times, while LN was associated with a decrease in hospital stay, analgesic use, complications and a faster return to normal activity. However, when pooling the RCTs, the decrease in OR time associated with ON was the only difference between the two groups. Surprisingly, no difference in hospital stay, analgesic use or time to normal activity was observed. This is an unexpected result since the two studies that looked at time to normal activity did show a statistical difference between the two groups [10,11].

Oncological outcomes

Only four series out of 11 compared the oncological outcomes between LRN and ORN (see Table 34.1) [16,19,22]. None of these have shown a SS difference in recurrence-free (RFS) or disease-specific (DSS) survivals. Ono et al. compared 40 ORN to 60 LRN performed between 1992 and 1998 [22]. Clinical T1 disease represented 10% of the ORN cases, while it represented 28% of cases for LRN. The remaining patients were cT2 preoperatively. RFS after 24 months of follow-up was 98% and 96% for ORN and LRN, respectively. Makhoul et al. compared 133 ORN with 134 LRN with similar tumor size and Fuhrman nuclear grades (p = 0.2 and 0.68, respectively) [19]. Mean tumor sizes were 4.8 and 3.9 cm for ORN and LRN while mean Fuhrman nuclear grades were 1.5 and 1.6, respectively. After a mean follow-up of 12 and 20 months (LRN and ORN), no recurrences were observed in either group. Finally, Hemal et al. compared the two approaches for T2-only tumors [16]. RFS and DSS were not SS between ORN and LRN (RFS = 90% both appro-ach, DSS = 94% (ORN) and 95% (LRN)). Of note, follow-up was longer by 6 months for ORN compared to LRN.

Comment

The advent of laparoscopy in urology has changed the surgical management of RCC. The initial enthusiasm for LRN was mainly related to its shorter hospital stay and reduced narcotic requirements after surgery. Early studies comparing the laparoscopic and open approaches for radical nephrectomy were biased by the comparison of laparoscopic to historical open series. Of note, most series have compared perioperative characteristics between the two approaches in a retrospective manner, rendering definitive conclusions difficult for a number of outcomes. In our opinion, subjective outcomes like hospital stay, complications, and transfusion rates are not valid if the criteria for discharge, complications or transfusions are not collected prospectively. For instance, ORN hospital stay varied from 3.6 to 21 days depending on the study chosen (see Table 34.1). Since laparoscopy was still in development and had to find its place as a new technique during the period of many of these studies, surgeons might have used different criteria to discharge their patients from hospital after one surgery versus another. On the other hand, some outcomes are less likely to be biased by subjective interpretation even if they are collected in a retrospective manner. For OR time and blood loss, we believe that conclusions regarding these specific outcomes are stronger. Another important factor to consider is that the size of the tumor in each group was not always compared in some studies [21,23]. This could have had an effect on factors like OR time or blood loss.

Despite these relative limitations in our analysis, certain conclusions can be drawn from the highest quality studies performed and the trends in the others. In our opinion, the study by Hemal et al. is the single best study to assess the perioperative and oncological outcomes comparing ORN with LRN because it was prospective and included only clinical T2 tumors [16]. In this study, it was shown that LRN was associated with a SS increase in OR time, but a SS decrease in hospital stay, blood loss, pain and transfusion rate. No SS differences in complications, RFS or DSS were observed between the two groups. All these conclusions are in agreement with most of the retrospective studies included in the analysis as well as the meta-analysis performed from the living donor kidney transplant literature. We believe that the combination of these studies is sufficient to draw conclusions on the aforementioned outcomes (see next section).

It is worth pointing out that, in addition to oncological outcome, another important outcome to assess when evaluating a patient candidate for RN is renal function. Even if LRN demonstrates advantages compared to ORN on many perioperative outcomes, there may be additional reasons to consider an open partial nephrectomy rather than a LRN. Increasingly, it is these two alternatives between which a decision must be made. Furthermore, when preclinical imaging shows enlarged lymph nodes or thrombus in the vena cava, management might be better suited to an open approach.

Implications for practice

Based on studies selected from the oncological and renal transplant literature, we believe there is sufficient evidence to show that LRN should be the first treatment option in patients with uncomplicated clinical T1 or T2 RCC not amenable to partial nephrectomy. The combined studies from radical nephrectomy series as well as those from living donor nephrectomy series have shown that LN is associated with a decrease in blood loss, transfusion rates, pain, time to normal activity and hospital stay (see Tables 34.2, 34.3). The decrease in OR time associated with ORN does not counterbalance the advantages of LRN when it is an option. Oncological outcomes appear to be similar for the two techniques, but the evidence for this is weaker. ORN should be considered for individual cases where an advantage is expected for the patient regarding oncological outcomes. The advantages might be a decrease in waiting time for surgery, removal of extensive lymph nodes, venous extension or concomittant metastasis.

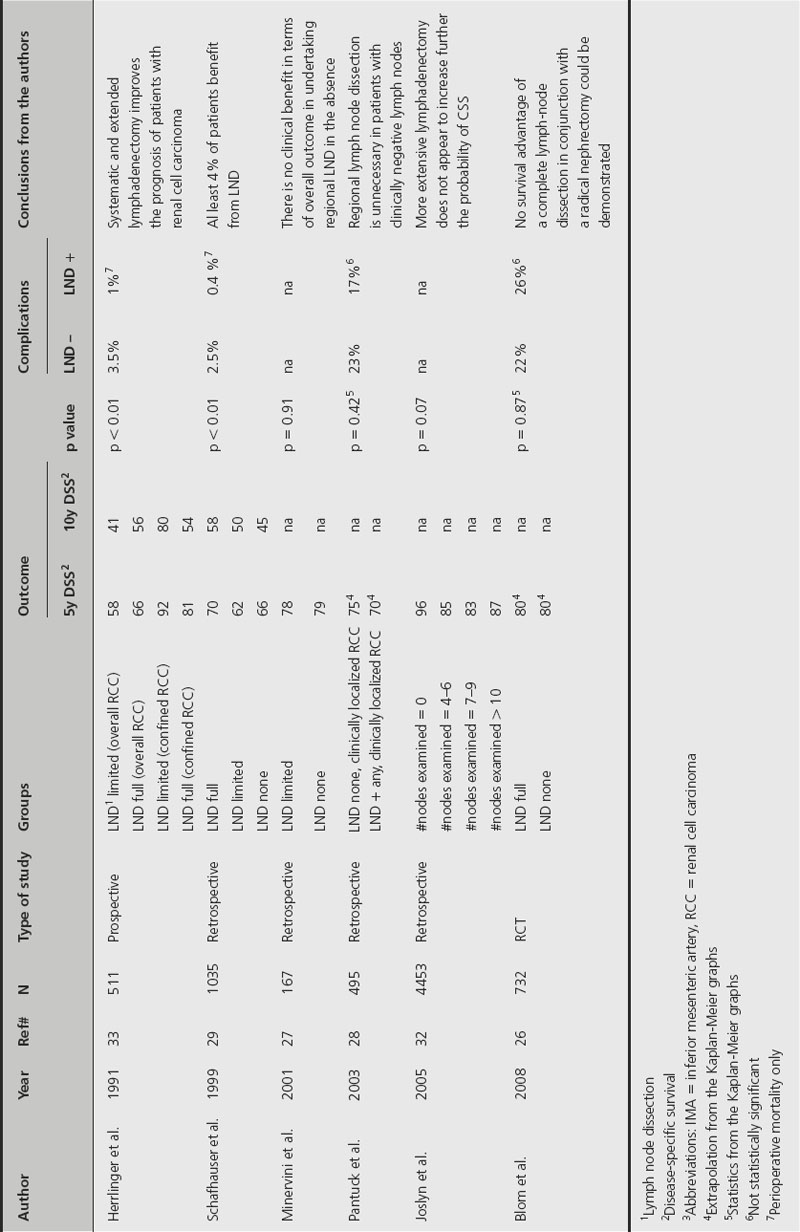

Table 34.3 Studies comparing perioperative and oncological outcomes of localized renal cell carcinoma treated with or without lymph node dissection (LND)

Recommendation

Laparoscopic radical nephrectomy should be strongly considered as the first option for patients with uncomplicated clinical T1 or T2 RCC not amenable to partial nephrectomy based on its reduced perioperative morbidity and equivalent oncological outcomes (strong recommendation, moderate-quality evidence, Grade 1B).

Implications for research

Research should now focus on prospective, randomized studies with oncological outcomes as the primary endpoint since evidence on perioperative outcomes is already strong.

Role of lymph node dissection in the treatment of localized renal cell carcinoma

Background

Lymph node metastasis may occur in up to 20% of cancers. In a recent review of the literature by Godoy et al., prevalence of LN metastasis was found in 3.3–66% of patients, depending on the extent of LN dissection or clinical cancer stage [25]. However, when considering only series that included nephrectomy for localized RCC, positive LNs were found less frequently, between 3.3% and 14.1% [26–30]. Primary landing zones of RCC metastasis are the interaortocaval nodes on the right and the para-aortic nodes on the left, though lymphatic spread from RCC is notoriously variable and unpredictable [25]. Advocates for LND propose it for two reasons: staging and/or therapeutic purposes. The initial template for RCC LND was described by Robson, and included paracaval, precaval, interaortocaval, preaortic and retroaortic LNs, extending caudally from the iliac bifurcation to the crus of the diaphragm cephalad [31]. Since then, the template has been modified through the years to include fewer lymph nodes, with the goal of decreasing morbidity. Limited LND was defined as including the pre-, retro-, and para-aortic and interaortocaval nodes on the right side and the para-, pre- and retroaortic nodes on the left side [27]. However, since the therapeutic benefit of LND has been debated, it has been difficult to recommend what would be the best LN dissection from a therapeutic perspective.

In this section, we will summarize the literature regarding some questions related to LND. The main question we have tried to answer is: Is there a therapeutic effect of LND in localized kidney cancer? We will also discuss the morbidity of LND for localized RCC.

Clinical question 34.2

What is the role of lymphadenectomy in localized RCC?

Literature search

Potentially relevant studies were identified by a search of the Medline electronic database (source PubMed, 1966 to December 2008) using relevant keywords in combination, as follows: renal cell carcinoma AND lymphadenectomy (313 articles retrieved), lymph node AND renal cell carcinoma OR kidney cancer (157 articles retrieved), lymphadenectomy AND kidney cancer (40 articles retrieved), lymph node dissection AND renal cell carcinoma OR kidney cancer (18 articles retrieved). Original AND review articles were selected based on language (English only) and revelance of their title. A total of 268 articles were kept for abstract analysis. Only studies from which we could distinguish outcomes for localized RCC to those from metastatic RCC were included. Studies evaluating the role of LND for metastatic RCC or preoperative enlarged nodes on imaging were not included.

The evidence

Oncological outcomes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree