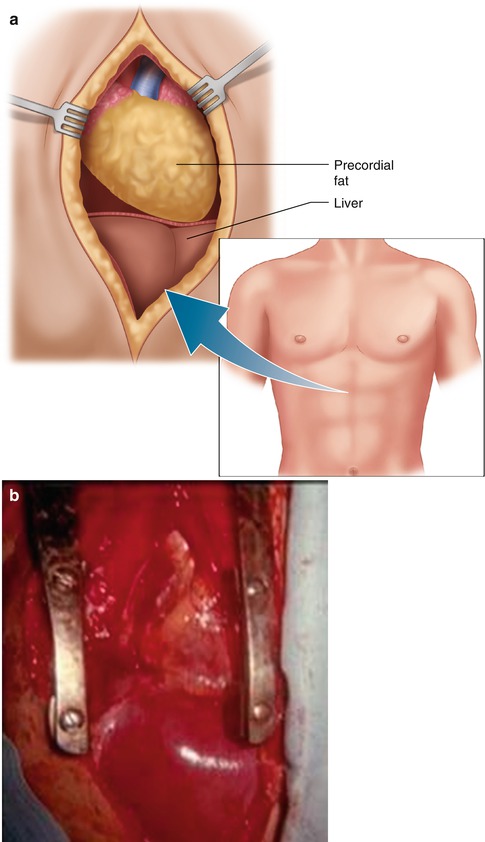

Fig. 2.1

Patients presenting with a large truncal defect in the right upper quadrant/right lower chest from a close-range shotgun blast or rifle wound (a) should be explored by an oblique incision which extends through the large defect and, if needed, can be extended inferiorly along the midline of the abdomen (b)

Fig. 2.2

The midline laparotomy provides the most practical approach to patients with both blunt and penetrating wounds involving the liver (a). This incision can then be extended superiorly as a median sternotomy in order to get control of bleeding from dome of the liver or from the hepatic veins (a). The diaphragm can be divided in the posterior midline to facilitate this control(b)

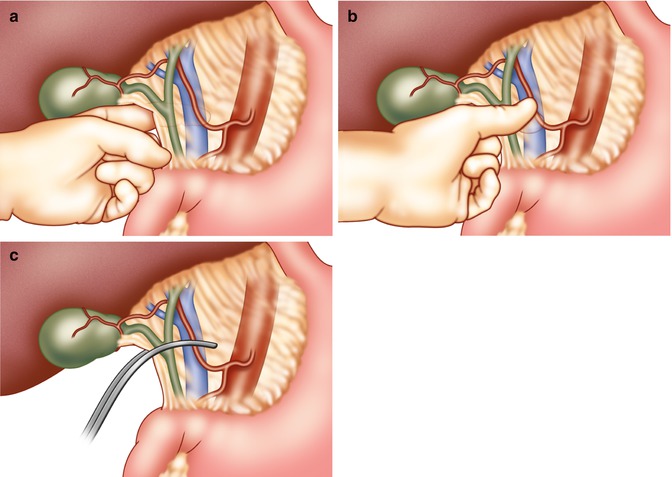

Temporary Packs

Upon entering the abdomen, rapid packing of all four quadrants allows the anesthesia team to catch up so that sequential life-saving treatment can be implemented on a priority basis [2, 10, 11]. When a major liver injury with active bleeding is identified, successful packing can usually be achieved by placing lap sponges above and below the liver and then using a large straight retractor to pull the liver up toward the diaphragm (Fig. 2.3). A penetrating wound adjacent to the gallbladder floss often can be controlled by a gauze pack but stressed by a Harrington retractor (Fig. 2.4) [2, 10]. The pack technique usually controls major hepatic bleeding; pressure should be maintained while bleeding from other sources is controlled and while a first-layer closure of hollow-viscus injuries is accomplished. When these latter objectives have been completed, the liver pack can be carefully removed. Often a major liver injury is no longer bleeding after pack removal. When this occurs, the injury should be left alone; aggressive palpation manipulation, especially probing “to see if there is any mushiness” within the liver, may lead to recurrent hemorrhage that is lethal. When the liver rebleeds after pack removal, they should be reapplied and pressure retraction reinstituted. This will provide an opportunity to achieve proper mobilization of the portion of the liver that needs to be approached surgically [2, 12, 13].

Fig. 2.3

Actively bleeding injuries from the right lobe can usually be temporarily contained by placing packs superiorly and inferiorly to the right lobe and then providing compression either digitally (a) or by way of the large right-angled retractor (b)

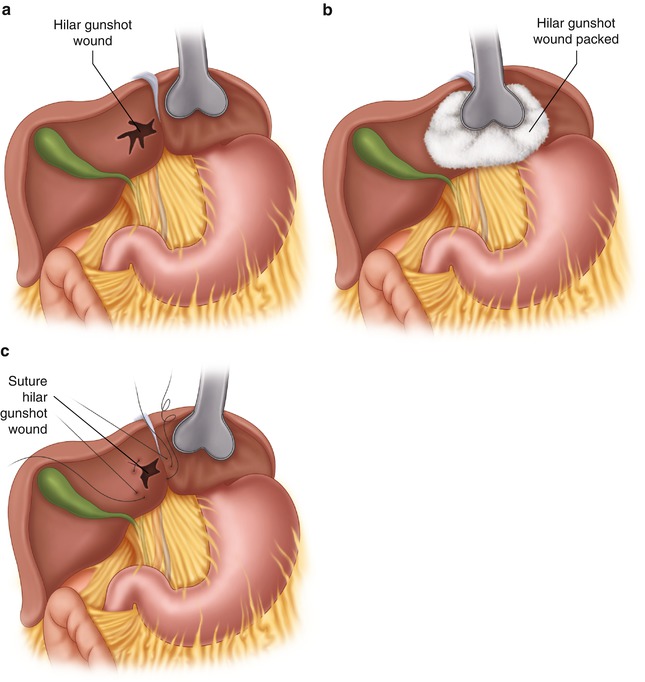

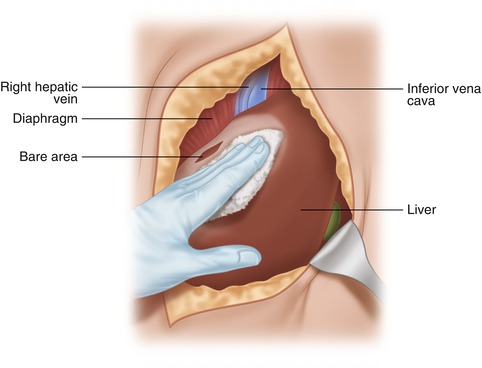

Fig. 2.4

Bleeding wounds near or at the hilum (a) can usually be contained by placing a pack and a Harrington retractor over the injury (b) until temporary hemostasis is obtained or slowed, at which time liver sutures placed on each side of the defect will provide hemostasis (c). Cholecystectomy is usually indicated in patients with these injuries

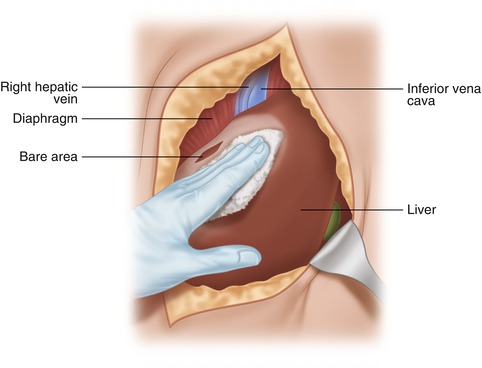

Hepatic Mobilization (Right Lobe)

The approach to hepatic mobilization varies according to the site and extent of liver injury. Mobilization of the right hepatic lobe in patients with major injuries near the right hepatic vein, or “bare” area of the liver, is most challenging [2, 13]. The right triangular ligament extends along the dome of the right lobe and can be divided in its1–2 cm width between the dome of the liver and the right hemidiaphragm (Fig. 2.5). When suprahepatic packs must be left in place to contain bleeding, this ligament can be divided throughout most of its length by Braille dissection. The bulk of the right lobe can then be mobilized inferiorly as the so-called “bare” area between the liver and diaphragm is reached (Fig. 2.6). The liver is mobilized anteriorly and medially as the “bare” area is dissected, being careful not to inadvertently perforate the diaphragm superiorly or dissect into the liver substance inferiorly [7, 13]. Further mobilization in the same direction provides access to the right hepatic vein, which rises on a superior portion of the liver and extends about 2 cm superiorly into the inferior vena cava (IVC, Fig. 2.5) [2, 12]. Careful dissection of the tissues medial to the right hepatic vein along with division of the diaphragmatic crura anteriorly permits access to the right hepatic vein/IVC junction.

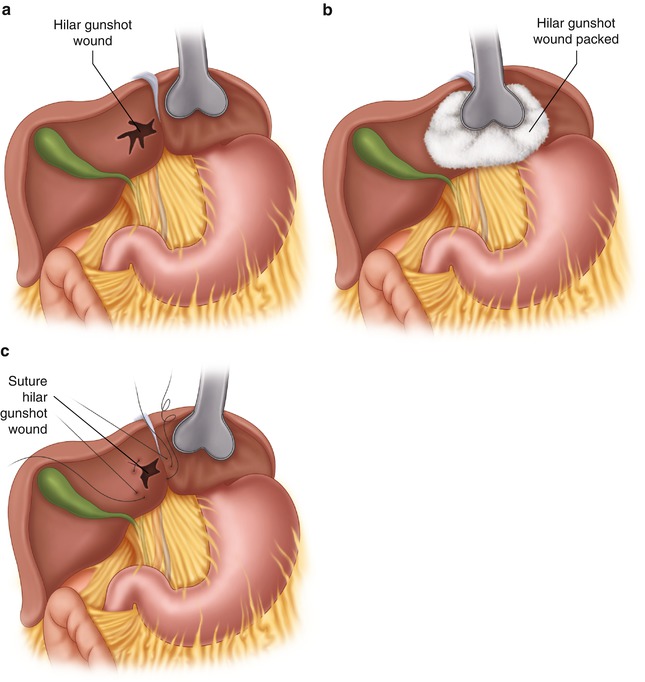

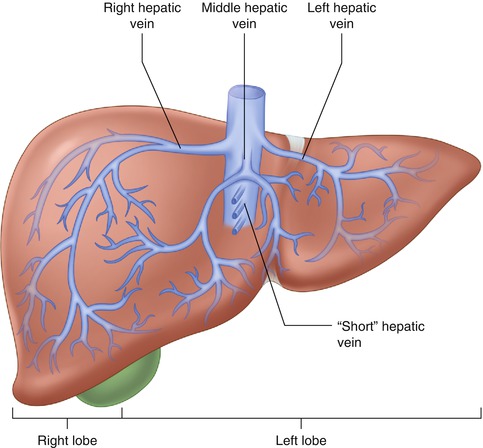

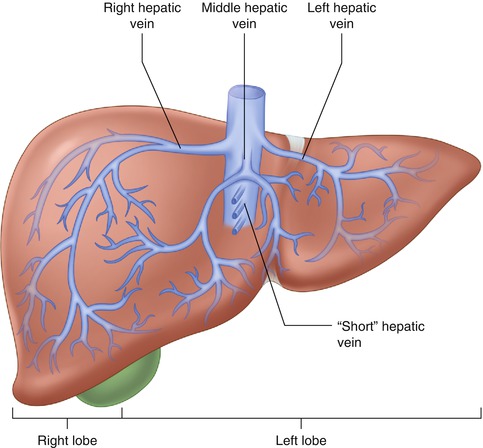

Fig. 2.5

Access to the right hepatic dome and right hepatic vein is achieved by mobilizing anteriorly and medially the right lobe beyond the bare area of the liver until the right hepatic vein is identified as it courses superiorly and posteriorly for about 2 cm to the IVC

Fig. 2.6

The “short” hepatic veins run from the caudate lobe to the anterior portion of the IVC. The authors prefer that, when divided, these veins be controlled by suture ligature or ties rather than with clips which can be pulled off the vein when they get attached to a sponge being removed. The classic hepatic venous system has separate entrance of the right, middle, and left hepatic veins into the IVC. Sometimes the middle hepatic vein and left hepatic vein join before entrance into the IVC

When further mobilization on the right lobe is needed in order to achieve anatomic resection, the right lobe can be retracted anteriorly, being careful to avoid injury to the right adrenal gland with its numerous vessels and, more medially, the short hepatic veins, which run between the caudate lobe and the inferior vena cava [2]. These veins need to be divided; the authors prefer suture ligature rather than clips, which sometimes catch onto sponges and yank off the divided veins (Fig. 2.6).

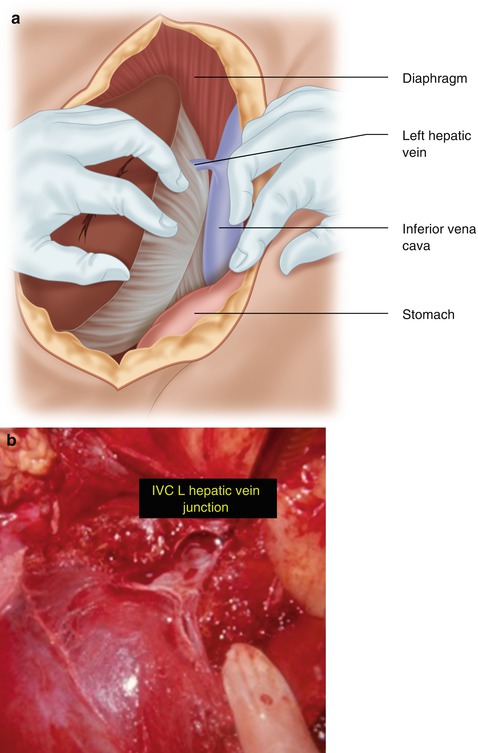

Hepatic Mobilization (Left Lobe)

Mobilization of the left hepatic lobe is much less challenging. The left triangular ligament between the left lobe and the left hemidiaphragm is more accessible and, therefore, more safely divided beyond the left lateral segment; this ligament is divided to the left medial segment where the left hepatic vein will be seen exiting on it and passing superiorly toward the left side of the IVC (Fig. 2.7) [2, 13]. The left hepatic vein usually flows directly into the IVC but, on occasion, may join with the mid-hepatic vein, in which case the entrance into the cava will be more medial. The short hepatic veins between the caudate lobe and IVC are usually not identified while mobilizing the left lobe. The entrance of the short hepatic veins is about 2–3 cm distal to the entrance of the middle and left hepatic veins into the IVC (Fig. 2.6) [2]. With full mobilization on the left lobe, however, these veins may be divided.

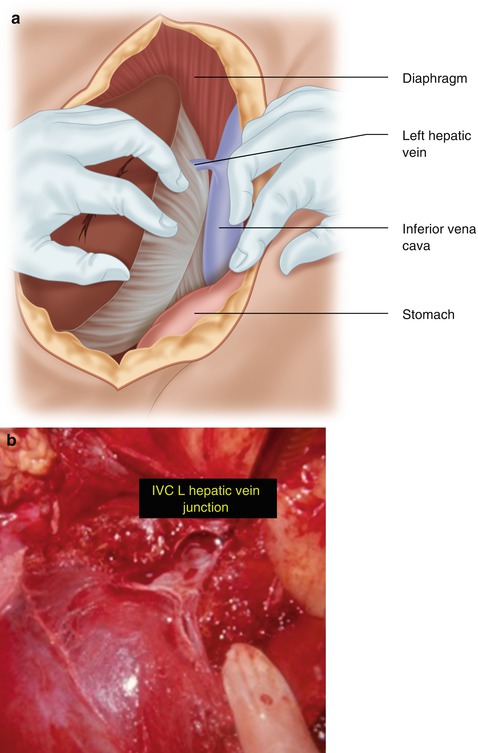

Fig. 2.7

The left hepatic vein usually flows superiorly and medially into the IVC and is accessed by dividing the left triangular ligament (a). After obtaining temporary control of the cava and left hepatic vein, the patient shown herein had rapid left hepatic lobectomy and oversewing of the left hepatic vein – IVC junction after placement of a Satinsky clamp (b). This type of patient salvage only occurs when God is not ready to receive the patient

Hepatic Inflow

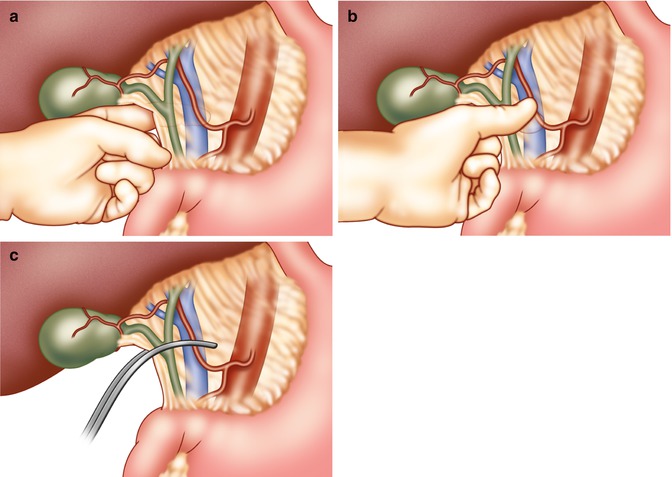

Control of arterial inflow is an important adjunct to hepatic mobilization. Temporary control can be achieved by the Pringle maneuver whereby one digitally compresses the portal triad just distal to the insertion of the cystic duct into the common bile duct (Fig. 2.8) [2, 12]. Temporary digital control can be achieved by Braille technique; vascular non-crushing clamps are used for longer term control. Long-term occlusion should not extend beyond 20 min at one time [13]. The individual branches of the hepatic artery and portal vein can then be dissected as one mobilizes the injured portion of the liver.

Fig. 2.8

The Pringle maneuver achieved with digital compression of the porta hepatis (a) not only provides good temporary inflow control of bleeding (b) but also is a predictor of the likelihood that hepatic dearterialization will contain active bleeding from a branch of the hepatic artery (c)

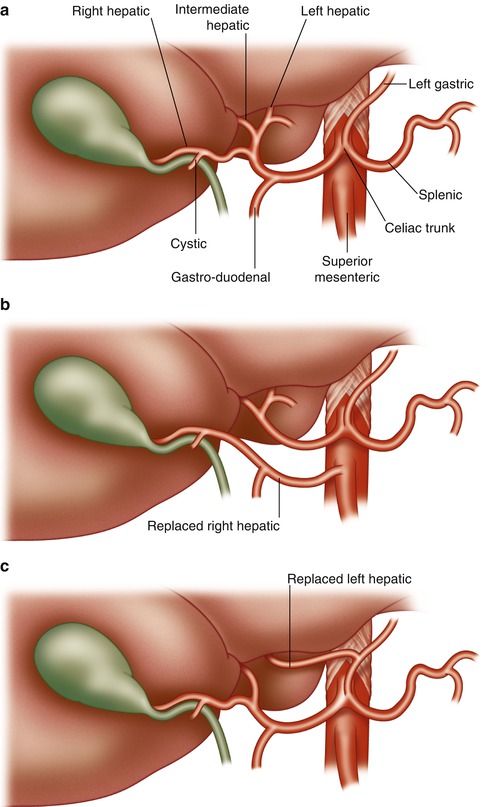

Vascular Anomalies

Although there are several anomalies of the hepatic arterial inflow, the most common occurs when the right hepatic artery arises as the first branch of the superior mesenteric artery; when this occurs, the right hepatic artery courses posterior to the pancreas and duodenum before curving superiorly toward the liver as the most lateral structure of the portal triad (Fig. 2.9) [2, 13]. Other less common anomalies of the hepatic arterial system include a common hepatic artery that rises from the superior mesenteric artery, a very proximal bifurcation of the common hepatic artery into the right and left hepatic arteries, and an accessory left hepatic artery that originates from the left gastric artery and perfuses the left lateral segment. The anomalous right hepatic artery provides oxygenation to all of the right lobe and the left medial segment. When this anomaly occurs, the left hepatic artery typically arises from the left gastric artery, passes through the lesser omentum, and provides oxygenation to only the left lateral segment. Portal venous anomalies are much less common.

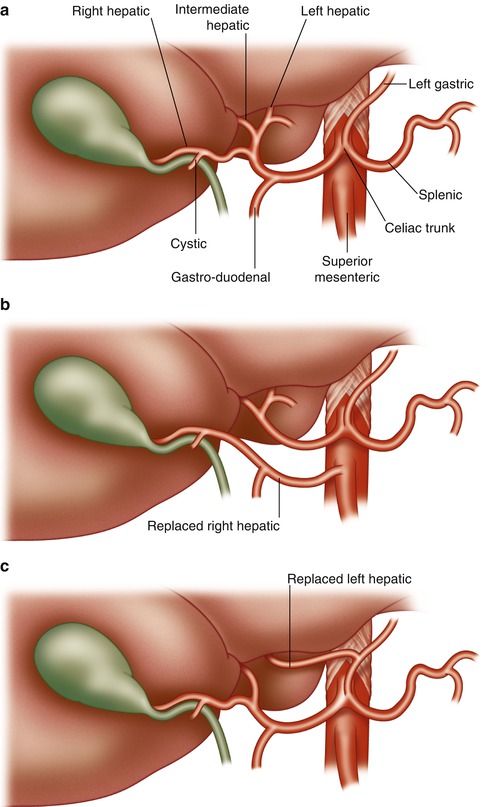

Fig. 2.9

Normal hepatic arterial inflow is shown (a) along with the two common anomalies, namely, the right hepatic artery originating from the superior mesenteric artery (b) and the left hepatic artery originating from the left gastric artery (c)

The Non-bleeding Wound

Often, when the packs that are used to obtain temporary control of the bleeding liver are removed, no rebleeding occurs. This wound should be observed and the surgeon should be certain that the patient is fully resuscitated and has stable vital signs. The non-bleeding, thus observed wound, should be left alone. Digital or instrument probing of the wound, as noted above, may lead to recurrent and sometimes lethal bleeding. Likewise, when a bullet has passed through the liver parenchyma into the hepatic vein and inferior vena cava with embolization to the right heart, the tract should be left alone and the known perforation of the retrohepatic IVC should not be explored (Fig. 2.10) [2]. No hemostatic techniques should be employed in a stable patient with a non-bleeding wound.

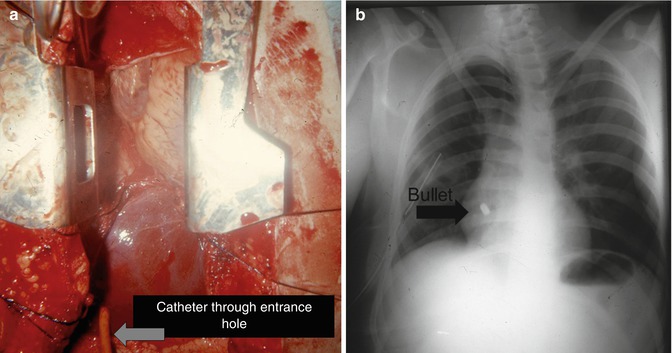

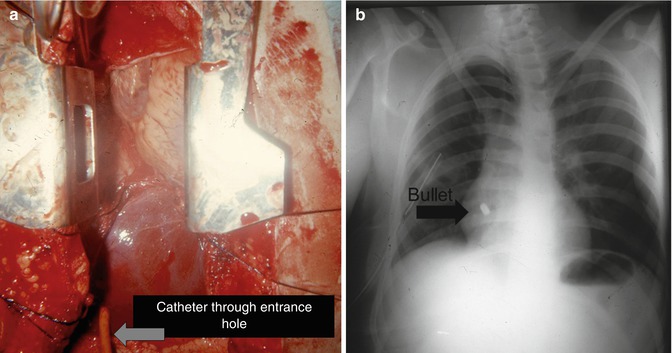

Fig. 2.10

When a missile passes through the substance of the liver with the tract depicted by the catheter (a) and ends up being embolized to the heart or lung (b), penetration of the anterior wall of the IVC is confirmed. This perforation along the anterior wall of the IVC should not be explored if there is no bleeding, whereas the bullet embolus can be dealt appropriately depending on its final location

During a prospective study of 637 patients who were operated upon for liver injury during a 5-year period, there were 280 patients in whom there was no bleeding after the liver packs were removed and the vital signs were stable [1, 2, 8]. These wounds were left alone, and not one patient had postoperative bleeding from the non-bleeding liver wound. Likewise, the isolated subcapsular hematoma should be left alone (see Fig. 2.13). Patients treated nonoperatively for intrahepatic hematomas usually have normal resolution of the hematoma; some patients, particularly intravenous drug addicts, will have bacterial seeding of the hematoma leading to an abscess, which can usually be drained percutaneously.

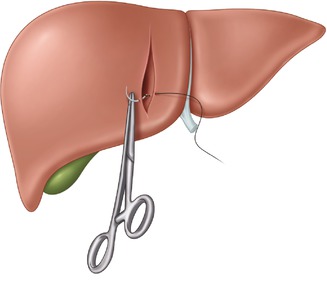

Hemostatic Techniques/Liver Suture

The simplest and most successful technique for obtaining hemostasis from bleeding liver wounds is hepatorrhaphy using liver sutures [2, 12]. These sutures are blunt tipped, two inches in length, and swedged on to a 2-O chromic suture (Fig. 2.11) [2, 14]. The blunt-tipped needle minimizes parenchyma damage while passing through the liver and can be easily grasped by the surgeons without fear of a needle injury. The suture should be passed through the full depth of the two-inch needle, well away from the bleeding margins with large deep bites (Fig. 2.11) [2]. The sutures are then approximated in order to bring the liver substance together without strangling it and hence creating liver necrosis (Fig. 2.12) [2]. This can often be best achieved by having the first assistant hold one of the strategically placed sutures so that the liver is compressed but not strangled while the surgeon ties a second suture in order to achieve the exact degree of compression without tearing or strangulation.

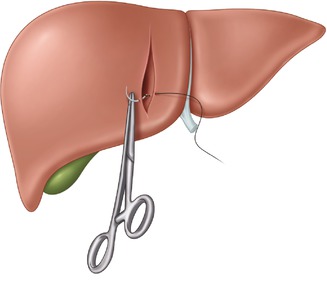

Fig. 2.11

Hepatorrhaphy or suture ligature of the liver is best achieved by using the 2″ blunt-tipped needle swedged onto a 2-O chromic suture. The sutures are placed well away from the wound and deep into the liver substance in order to obtain compression hemostasis of those vessels which are within 3 cm of the liver capsule

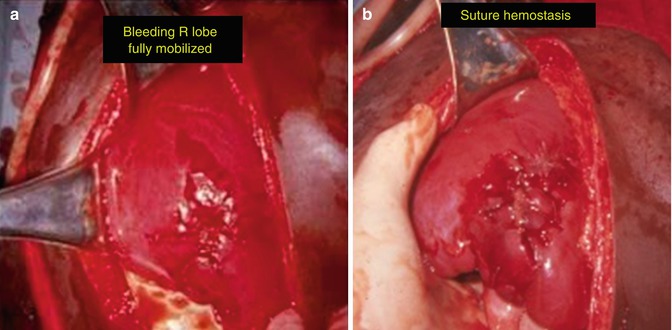

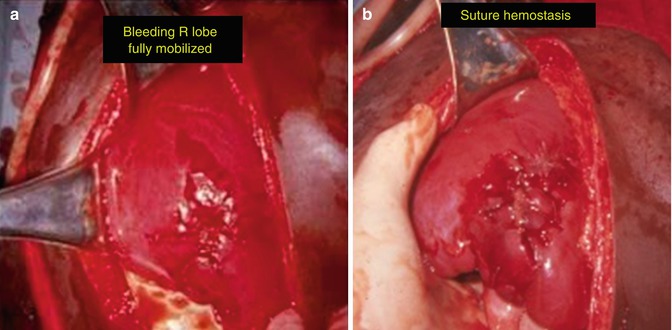

Fig. 2.12

After full mobilization of an actively bleeding right lobe of the liver (a), deep liver sutures usually achieve complete hemostasis without causing parenchymal ischemia (b)

One of the controversies regarding hepatorrhaphy concerns the patient with active bleeding through both the entrance and the exit sites of a liver gunshot wound. The fear of closing both the entrance and exit wounds is that there will be continued intrahepatic bleeding, which may cause a need for reoperation or become contaminated and result in an intrahepatic abscess [2]. Actually, most bleeding from the through-and-through liver wound arises from liver parenchyma within 2 cm of the capsule; the authors have successfully closed both ends of a through-and-through tract with a good hemostasis and without having the above complications [2]. In patients in whom both ends of the missile tract have been closed with liver sutures, rebleeding through the liver sutures from the unopposed deeper structures will be readily apparent within five minutes of tying the liver sutures. When this occurs, the liver suture must be removed and some other hemostatic technique employed.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree