Subtotal1: 9 instillations

Subtotal2: 18 instillations

The total number of instillations is 9 + 18 = 27 for a total drug cost of approximately 1955 euros.

Because of the side effects, only 16 % of the patients can tolerate the complete treatment [8]. On the other hand, the interest in the BCG maintenance therapy has been questioned due to differences in the published results on the efficacy on recurrence and tumour progression when comparing the maintenance and non-maintenance groups [11].

Many alternatives have been proposed to Lamm’s protocol, mainly by reducing the dose or prolonging the break period between two instillations: A Spanish study has shown no significant difference in recurrence and progression rates between the standard dose group (81 mg) and a 1/3 (one third) dose (27 mg) group with significantly less side effects in the latter [12]. Despite criticism for the lack of randomisation in this study, it still has merit in suggesting that BCG maintenance doses could be reduced for the intermediate-risk group without jeopardising the oncological outcomes.

A recent meta-analysis has demonstrated that maintenance treatment was associated with a better progression-free survival but produced more side effects. Also the standard maintenance dose was superior to the reduced dose, and the combination of BCG with mitomycin C or interferon α-2b did not result in significant oncologic improvement compared to BCG alone [13].

The Lamm (or SWOG) maintenance treatment protocol is actually the most utilised therapy because it is based on a randomised study of a large cohort population (550 patients).

Side Effects of BCG Instillation

These are often minor causing the irritable bladder syndrome (increased urinary frequency, urgency and dysuria) sometimes accompanied by transient low-grade fever and haematuria. They generally respond to a symptomatic treatment and don’t require admission. In <1–3 % however severe systemic manifestations (high fever, uraemia, jaundice, asthenia, hypotension and septic shock) may occur within hours or days after the BCG instillation, requiring admission and rarely even intensive care treatment [14, 15]. If bacteraemia from the live vaccine occurs through a urothelial breach, e.g. during traumatic catheterisation [16], the clinical aftermath will depend on the patient’s immunological status, and symptoms may occur hours, days, months or even years later [15, 17].

Summary of the Side Effects

Allergy: skin manifestations (rash) and joints pain.

Inflammatory syndrome: transient fever and asthenia.

Others: urinary tract infection, haematuria, increased urinary frequency, dysuria, bladder contracture, symptomatic granulomatous prostatitis and/or epididymo-orchitis, ureteral obstruction and renal abscess.

Systemic reaction to the BCG (rare but serious): fever ≥39.5 °C lasting for at least 12 h or ≥38.5 °C lasting for at least 48 h and/or visceral involvement (essentially the lung and/or the liver). Disseminated BCGitis has been recognised over many years manifesting as granulomatous infiltration in the lungs, liver and/or bone marrow [15]. Potentially lethal complications such as sepsis and shock are very rare events.

Prophylactic Measures to Prevent or Minimise Side Effects

Ofloxacine: One tablet 200 mg can be taken 6 h after the first post-procedure micturition and again 12 h later. This has been shown to significantly reduce class 2 (moderate) and class 3 (severe) side effects by 18.5 % without affecting the 12-month recurrence-free survival [18].

Pre-emptive antituberculous drugs: These limit the stimulation of the immune reaction and could reduce the effectiveness of the antitumoural action.

BCG dose reduction: During the maintenance period, the dose can be reduced to half or a third, but the standard dose must be maintained whenever possible for high-risk or multifocal tumours [19].

Management of Adverse Events

This depends on their seriousness [20]:

Low-grade fever and irritative symptoms: They generally subside within 48 h and do not require any specific treatment, apart from antipyretics (paracetamol) and antispasmodics (butyl-hyoscine: Buscopan®). If the fever persists, urinary infection should be ruled out before starting a 2-week course of isoniazid.

Regional complications such as granulomatous prostatitis or epididymitis require a 3-month course of isoniazid with rifampicin.

Systemic infections such as granulomatous nephritis and abscesses, pneumonitis, hepatitis and osteomyelitis are treated with a 6-month course of the triple therapy isoniazid-rifampicin-ethambutol.

Life-threatening adverse events (either due to septicaemia or to immunoallergic reactions) may be delayed several months or even few years after the end of BCG therapy and require urgent treatment with antituberculous drugs and prednisolone.

7.1.3 Radical Cystectomy (RC)

RC is considered optional in high-risk T1 (high-grade, multifocal, large-size) tumours and in carcinoma in situ. It should be considered for all T1 tumours unresponsive to intravesical therapy; however, the possibility of performing a partial cystectomy should be considered initially if the tumour is suitably located (bladder dome). It is also recommended if CIS does not completely respond to a course of BCG induction and six maintenance instillations [23].

Take-Home Message: Treatment of NIMBT and MIBT

Primary treatment | TURBT, complete and deep to the muscle layer |

Second TURBT to be done within 2–6 weeks in the following cases: | |

After an incomplete initial procedure (large-size or multiple lesions) | |

If there is no muscle in the initial resection, except for Ta G1 and primary CIS | |

In all T1 tumours | |

In all G3 tumours, except primary CIS | |

Follow-up after primary treatment | Low-risk tumours: cystoscopy at 3, 6 and 12 months and then yearly for 5 years |

Intermediate risk: cystoscopy + urine cytology at 3, 6 and 12 months and then yearly for 10 years | |

High risk: cystoscopy + urine cytology at 3, 6 and 12 months and then yearly for life | |

Adjuvant intravesical instillation (for intermediate- and high-risk groups) | Cytotoxic agents for low-grade tumours: now mitomycin C is mostly used. Gemcitabine is another promising drug |

Immunotherapy for high-grade tumours: uses mainly the BCG vaccine in different strains. The induction schedule followed by the Lamm maintenance protocol (SWOG) is more effective but has many side effects | |

Radical cystectomy | Optional in high-risk T1 (high-grade, multifocal, large-size) tumours and in carcinoma in situ |

Should be considered for all T1 unresponsive to intravesical therapy (a partial cystectomy is to be considered when tumour is favourably located) | |

Recommended for a CIS when complete response is not reached after the BCG induction and six maintenance instillations | |

Localized MIBT | Radical cystectomy (RC) is the treatment of choice. To be performed within 3 months of diagnosis and to include PLND |

If no contraindication and technically possible, a substitution orthotopic entero-cystoplasty should follow the RC to preserve the bodily image. Otherwise, urinary derivations to be done through ileal conduit (incontinent, Bricker, or continent, Cock, Indiana, etc.) or direct urostomies | |

Bladder-sparing strategies: EBRT or brachytherapy for patients unfit for surgery, partial cystectomy and TURBT with concomitant radio-chemotherapy for highly selected patients | |

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (cisplatin based) advised before either RC or EBRT | |

Adjuvant chemotherapy not recommended outside clinical trials | |

Neoadjuvant EBRT not recommended | |

Locally advanced | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

pT3 and pT4 N+ tumours with positive SM: to be included in clinical trial for adjuvant chemotherapy | |

Metastatic MIBT | Two independent factors have a negative impact on the patient’s survival: the altered G-C (PS >1) and the presence of visceral metastases |

1st line: MVAC regimen equal to G-C protocol, but the latter has a better toxicity profile | |

Patients ineligible for cisplatin (PS 2 or creatinine clearance <60 ml/min) can be proposed a gemcitabine monotherapy (overall survival limited to 1 year) or a combination gemcitabine-carboplatin | |

2nd line: vinflunine (Javlor®) | |

Unfit patients: Supportive treatment and pain management only. Zoledronic acid and denosumab if bony metastases |

7.2 MIBT

EAU expert panel recommends the following information be contained in an HPR of an MIBT: the histological subtype, the depth of tumour invasion, the resection margins status including the eventual presence of CIS and the extensive lymph node representation. Optionally the report may also include the lymphovascular invasion status [24]. However, there are pitfalls that urologists should be aware of with regard to pathological studies of TURBT specimens:

Pathologists consider any tumour crossing the basal membrane of the bladder mucosa and invading the lamina propria as infiltrating. Therefore, urologists must cautiously read the pathologist’s report and not consider all the tumours that are reported to be infiltrating as muscle-invasive, i.e. mistake T1 for T2 tumours.

Muscularis mucosae hyperplasia seen in chronic inflammation may be mistaken for the muscularis propria and give a false impression of muscular infiltration [25].

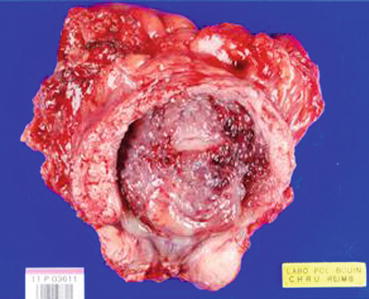

The presence of a fatty tissue inside the tumour proliferation is not synonymous with pT3 stage (extra-vesical), since the fatty tissue has been also described in the muscular layer as well as in the deep layer of the lamina propria [26]. Therefore, a reliable diagnosis of the pT3 stage can only be established in a cystectomy specimen (Fig. 7.1).

Fig. 7.1

A cystectomy specimen showing an exophytic and endophytic bladder carcinoma (Courtesy of A. Durlach, Pol Bouin Laboratory, University Hospital of Reims, France)

It is impossible to differentiate the stages pT2a and pT2b in a TURBT specimen.

It is difficult to determine the stage for tumours developing inside a bladder diverticulum; due to the absence of a muscle layer, there are two possibilities in this setting: either pTa tumour or extra-vesical extension.

The treatment options of MIBC depend on whether the disease is metastatic or not.

7.2.1 Non-metastatic MIBC

7.2.1.1 Radical Cystectomy

Radical cystectomy (RC) is the treatment of choice for non-metastatic urothelial MIBC (T2-T4a, cN0M0), as well as for non-urothelial bladder tumours and for non-MIBC with high risk of progression after failed conservative treatment. RC must include removal of regional lymph nodes. Despite the above indications, this procedure is considered optional in patients over the age of 80 years for whom an onco-geriatric assessment is important to weigh the advantages and the risks of major surgery. The decision to consider bladder-sparing treatment versus cystectomy in the geriatric population with invasive bladder cancer should be based on a validated score which considers tumour staging, comorbidities and perioperative mortality, such as the Charlson comorbidity index [30] (Table 7.1).

Table 7.1

Charlson comorbidity index

Scores | Age (years) | Comorbidities |

|---|---|---|

0 | <40 | |

1 | 41–50 | Myocardial infarct, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, dementia, cerebrovascular disease, chronic lung disease, connective tissue disease, ulcer, chronic mild liver disease, uncomplicated diabetes |

2 | 51–60 | Hemiplegia, moderate or severe chronic kidney disease, diabetes with end organ damage, non-metastatic solid tumour, leukaemia, malignant lymphoma |

3 | 61–70 | Moderate or severe liver disease |

4 | 71–80 | |

6 | Metastatic tumour, AIDS (not just HIV positive) |

A statistically significant correlation exists between the diagnosis-to-cystectomy time interval and the final pathological stage, with a delay of more than 3 months increasing the stage of the tumour and consequently reducing the rate of localised bladder cancer from 81 to 52 %. Specifically, patients with an interval greater than 90 days were more likely to have pT3 or higher [31].

RC should always be done within 3 months of the diagnosis to minimise the risks of progression and disease-specific mortality.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Only gold members can continue reading. Log In or Register to continue

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree