, Ivan Damjanov1 and Ryan M. Taylor2

(1)

University of Kansas School of Medicine, University of Kansas, Kansas City, KS, USA

(2)

Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City, KS, USA

Liver transplantation is currently the ultimate treatment of choice for previously incurable liver diseases, which fall into four categories as follows:

Cirrhosis, i.e., end stage chronic liver disease

Acute liver failure with submassive or massive liver necrosis

Malignant liver tumors

Chronic metabolic or genetic diseases

Cirrhosis due to chronic viral hepatitis C and B, as well as alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis account for the majority of cases. This group also includes so called cryptogenic cirrhosis, which is believed by most authorities to be due to precedent non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Less common causes of end stage liver disease such as primary biliary cirrhosis, autoimmune hepatitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis are also found in a significant number of patients. Overall, cirrhosis is found in approximately 70–80 % of all patients receiving liver transplants. Acute liver failure due to acetaminophen toxicity, fulminant viral hepatitis and a number of drugs and toxins account for about 5–10 % transplants. Malignant tumors account for 10 % and the metabolic/genetic diseases account for less than 5 % of all liver transplantations. Approximately 15 % of liver transplantations are performed for failure of the first transplant, and 1–2 % represent repeat transplantations on persons who already had two previous transplantations (Hübscher and Clouston 2012; Demetris et al. 2015).

Liver biopsy is widely used to evaluate the donor liver as well as the changes that may occur in the liver transplant. In general terms the most important problems facing pathologists who deal with liver transplants can be classified as follows:

Quality of the graft which translates to graft viability

Graft preservation/reperfusion injury

Vascular and biliary duct injuries related to transplantation

Immune-mediated transplant rejection, including acute and chronic cell mediated rejection and antibody mediated rejection

Complications of immunosuppressive therapy, including opportunistic infection and PTLD

Recurrence of the original or primary liver disease

Development of an additional liver disease that did not exist in the donor or the graft

Quality of the Graft

Quality of the grafts obtained from deceased donors is assessed in frozen sections preferably using at least two core needle biopsies and a wedge biopsy specimen. The most important features evaluated in biopsies of donor livers include fatty change, necrosis, fibrosis and inflammation. These pathologic findings are interpreted in conjunction with clinical data provided about the potential donor. To increase the number of potential donors special criteria have been developed for extended criteria donors (ECD). These criteria include donor age >60 years of age, > 40 % macrovesicular steatosis, cold ischemia time over 12 h, donation after cardiac death (DCD) and donor exposure risks including history of active injection drug abuse and incarcerated status to mention just a few (Demetris et al. 2015).

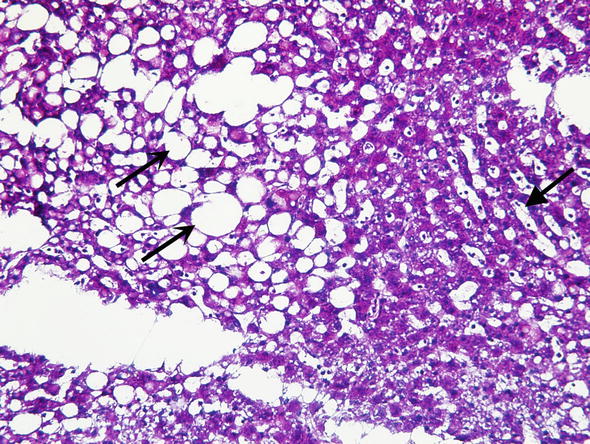

Macrovesicular fatty change. Macrovesicular steatosis involving 10–30 % hepatocytes can be acceptable for transplantation. However, donor livers showing more than 30 % of macrovesicular fatty change are considered high risk and many times unsuitable for transplantation (Fig. 1). Such livers are prone to preservation/reperfusion injury and the transplantation is associated with reduced graft survival. Livers showing moderate macrovesicular steatosis, in the range from 10 % to 30 %, are considered for transplantation on an individual basis in context of ECD. Most of the fat is cleared from hepatocytes during the first 3 weeks after transplantation (Hübscher and Clouston 2012).

Fig. 1.

Donor liver biopsy. Frozen section of potential donor liver biopsy. Care must be taken to distinguish frozen section artifacts such as dilated sinusoids due to water (closed arrow) and true fat vacuoles (open arrows). This frozen section was interpreted as 50 % steatosis which is suboptimal for liver transplantation

Necrosis. If cellular necrosis involves more than 10 % of all hepatocytes the liver is considered unsuitable for transplantation. Subcapsular necrosis is common in wedge biopsies due to manipulation of the organ during harvesting and this it should be diagnosed only if present in core needle biopsies.

Fibrosis. Donors are disqualified if the liver shows bridging fibrosis, incomplete or complete cirrhosis.

Inflammation. Donors are disqualified if the liver shows prominent portal inflammation or inflammation extending from the portal tracts into the lobules. Livers from donors infected with HCV can be considered for transplantation into HCV positive recipients if the inflammation is mild and the stage of fibrosis is less than Ishak Stage 3/6 (no evidence of bridging fibrosis). Additionally with the advent of new highly effective and well tolerated HCV therapies, there may be relaxation in use of grafts positive for HCV in the future.

Comments

1.

Livers from donors who have malignant tumors or have advanced atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease are not suitable for transplantation.

2.

Small vacuolar steatosis (previously known as “microvesicular steatosis”) does not adversely affect the fate of the graft and is not considered to be a risk factor unless severe.

3.

Most living donor livers are not biopsied prior to transplantation, unless the donors have some potential risk factors. The extent of macrovesicular steatosis in obese donors can be reduced by preoperative dietary regimens. Not all obese donors have fatty changes in more than 30 % hepatocytes (Demetris et al. 2015).

Graft Preservation/Reperfusion Injury

Preservation/reperfusion injury may occur during cold ischemia (while the liver is stored in preservation fluid), warm ischemia (upon reestablishment of the blood circulation) or in the perioperative period (Demetris et al. 2015). Clinically it presents with liver dysfunction characterized by poor bile production and elevation of serum lactate levels in the early post-transplantation period. Pathologically this is seen as focal liver cell necrosis accompanied by acute inflammation which is followed by regeneration and repair 1–2 days thereafter. Since liver biopsies are usually not performed during the first days after transplantation, the changes are typically seen weeks to months after the transplantation. Preservation/perfusion injury related changes may persist for 1–2 months and resolve thereafter without any serious consequences. A significant number of patients will however show irreversible and progressive changes that will reduce the survival of the graft. In particular, these grafts are at risk for ischemic cholangiopathy.

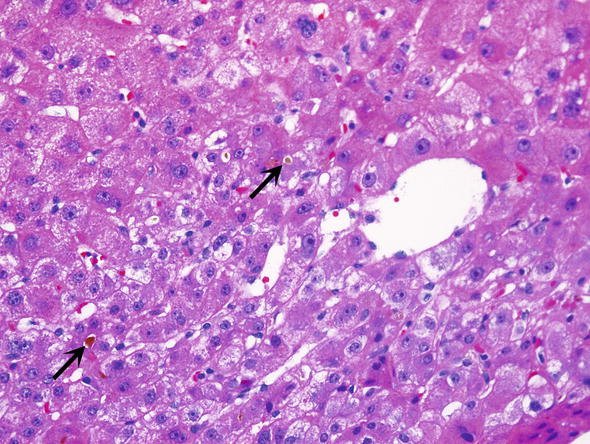

Changes related to graft preservation/reperfusion injury can be usually graded as mild, moderate or severe. Severe preservation injury shows hepatocyte swelling and canalicular cholestasis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Preservation/reperfusion. Biopsies from grafts which have preservation/reperfusion often show canalicular cholestasis (arrows)

Mild injury. In biopsies performed a few days after the transplantation there is evidence of regeneration of hepatocytes marked by mitotic figures, variation of nuclear size (anisocytosis), and expansion of liver plates, which are 2–4 cell thick.

Persistent mild to moderate injury. In addition to signs of regeneration there are signs of centrilobular liver cell swelling and canalicular cholestasis.

Persistent severe injury. In addition to signs of regeneration there is more pronounced centrilobular liver cell swelling and canalicular cholestasis. Furthermore there is portal and periportal bile ductular proliferation with cholangiolar cholestasis. The periportal reticulin framework shows signs of collapse and liver cell dropout, corresponding to previous liver cell necrosis.

Comments

1.

Fatty change of hepatocytes in excess of 30 % predisposes the liver to more pronounced preservation/reperfusion injury.

2.

Cold ischemia longer than 12 h is a significant risk factor.

3.

Donation after cardiac death (DCD) is associated with an increased incidence of preservation/perfusion injury which may result in ischemic cholangiopathy and higher risk of graft loss in the future.

4.

Infection and sepsis may develop and aggravate the injury.

Vascular and Biliary Duct Injuries Related to Transplantation

∎ Vascular injuries that occur during transplantation are relatively rare. They are related to technical difficulties during surgery, as well as anatomic, metabolic, or physiologic abnormalities. Injuries may lead to hepatic artery and vein or portal vein thrombosis and ischemia, resembling those vascular phenomena in native livers.

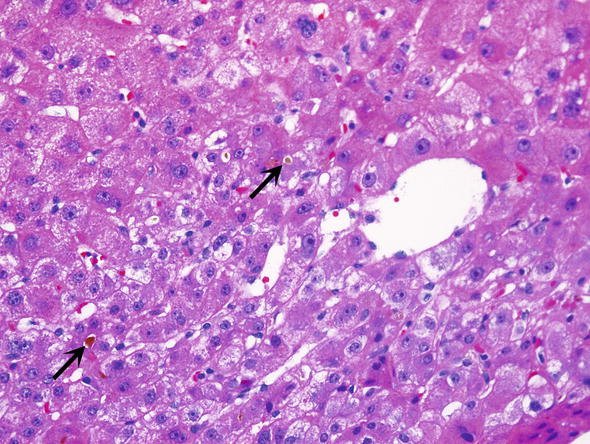

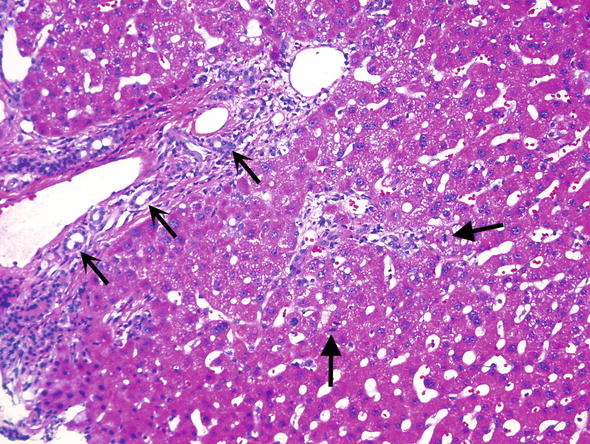

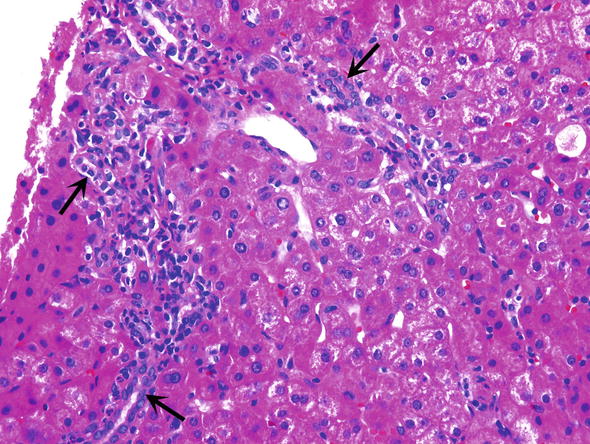

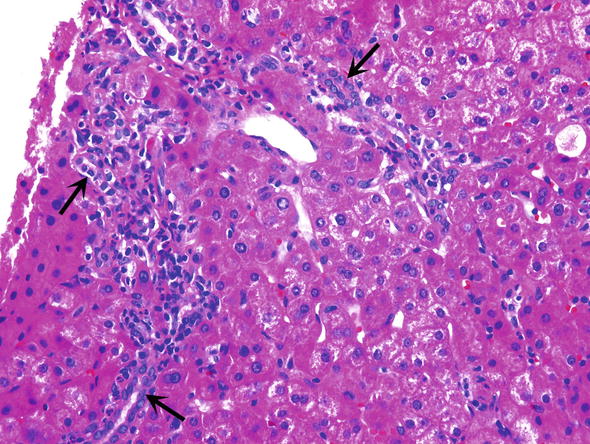

∎ Hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) is the most common vascular complication related to transplantation and usually occurs within the first month post-transplant. Allografts are particularly susceptible to ischemia related to HAT due to the lack of collateral blood supply. Since the hepatic artery supplies the biliary tree, the subsequent changes which occur are referred to as ischemic cholangitis or ischemic cholangiopathy. Microscopically, these changes are identical to those seen in biliary tract obstruction/stricture and encompass ductular proliferation, acute pericholangitis, and portal tract edema. In addition, there are usually abundant hepatocyte mitotic figures (Fig. 3). In any post-transplant biopsy showing a ductular reaction, hepatic artery thrombosis should be excluded. Grafts requiring reconstruction or alteration of the native anatomy are predisposed to this form of injury.

Fig. 3.

Hepatic artery thrombosis. Biopsies from patients with hepatic artery thrombosis show bile ductular proliferation (open arrows) and numerous hepatocyte mitoses (closed arrows)

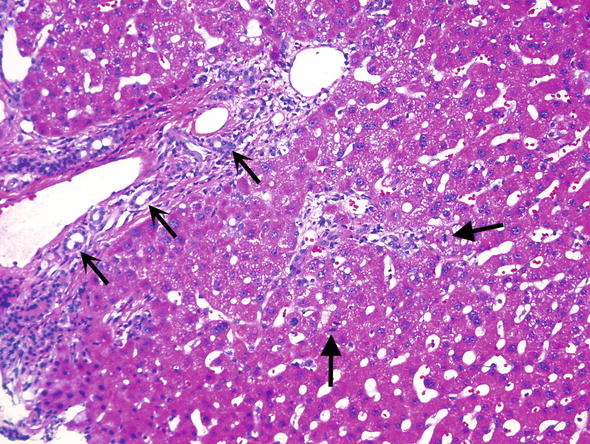

∎ Biliary duct injuries are among the most common complication of liver transplantation, and are found in up to 20 % recipients (Demetris et al. 2015). Pathologic changes are similar to those seen in biliary obstruction in native livers. Anastomotic strictures usually occur within the first couple months and non anastomotic strictures usually occur after 1 year. Characteristic features of biliary tract obstruction/stricture included ductular proliferation, acute pericholangitis and cholangitis, and centrolobular cholestasis (Fig. 4). Lobular collections of neutrophils belong to early findings. Biliary changes can be progressive and ultimately lead to ductopenic biliary fibrosis and graft loss.

Fig. 4.

Biliary tract obstruction. Biliary tract obstruction is characterized by ductular proliferation (arrows) and acute pericholangitis

Comments

1.

Biliary duct injury related changes in the early stages must be pathologically distinguished from T cell mediated rejection, formerly acute cellular rejection (ACR). Portal inflammation caused by obstruction is characterized by periductal edema and infiltrates of neutrophils. Typically, the bile ducts show little epithelial damage, unless the obstruction/stricture has been long standing. In ACR the inflammatory infiltrates are mixed and composed of larger (blastic) and small lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and neutrophils. Lymphocytes invade bile ducts, and their nuclei enlarge and become irregularly shaped. In many cases there is also perivenular lymphoblastic infiltration.

2.

Chronic stages of biliary obstruction are characterized by lymphocytic infiltrates, senescent bile duct changes, and progressive ductopenia. These changes may be difficult to distinguish from chronic transplant rejection, recurrent viral hepatitis C or autoimmune hepatitis. Expansion of portal tracts due to stellate fibrosis and ductular reaction in some of them favors the diagnosis of obstruction. Small portal tracts, inconspicuous ductular reaction and perivenular fibrosis combined with pure lymphocytic or mixed lymphocytic and plasmacellular infiltrates favor the diagnosis of chronic rejection (Demetris et al. 2015).

3.

A liver damaged by chronic obstructive cholangiopathy can be markedly enlarged, whereas those showing signs of chronic transplant rejection are of normal size or smaller (Demetris et al. 2015).

Acute Cellular Rejection

Acute cellular rejection (ACR) or T cell mediated rejection is related to an immune-mediated response of the host affecting bile ducts and blood vessels. Most cases occur within first few weeks to several months after transplantation but can develop even years thereafter. Historically rates of rejection have been decreasing due to the effectiveness of current immunosuppression regimens. The pathologic hallmarks of ACR include (a) portal inflammation, (b) bile duct inflammation/damage, and (c) venous endotheliitis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Banff grading liver allograft rejection—Rejection Activity Index (RAI)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree