Adenomas

Carcinoid tumors

Anastomotic stricture

Anastomotic leak

Rectovaginal and rectourethral fistula repair

Retrorectal tumors

Drainage of pelvic abscess

Rectal foreign body removal

Low-risk T1 rectal cancer

Palliation of advanced rectal tumors

Transanal NOTES (natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery)

Since its initial development, equipment and access techniques for TES have evolved considerably leading to technical advances and increased adoption. The original rigid metal platforms (Richard Wolf Medical Instruments Corporation, Illinois, USA) include a beveled rigid proctoscope (40 mm wide), side ports for CO2 insufflation, airtight face plate, stereoscopic camera, three ports for instrument placement, and customized operating tools. An alternative rigid platform is the TEO platform (KARL STORZ GmbH & Co. KG, Tuttlingen). Since its inception, enthusiasm has brought the development of newer platforms under the term transanal minimally invasive surgery (TAMIS) [8]. New access devices utilize standard laparoscopic equipment making adoption for surgeons already using single-incision laparoscopic platforms easier.

Indications

Rectal Adenoma

TES is now the procedure of choice for removal of endoscopically unresectable adenomas of the rectum. The initial indication for TES was to aid in removing endoscopically unresectable adenomas that were in the mid to proximal rectum, unreachable by conventional anoscopy, and that would otherwise require low anterior resection. Relative to standard transanal excision, TES has been shown to be having improved outcomes. Moore et al. in 2008 compared TEM to standard transanal excision for rectal neoplasms most of which were adenomas or pT1 carcinoma. TEM was more likely to yield clear margins (90 % vs. 71 %) for all specimen types and lower recurrence (5 % vs. 27 %) specifically for patients with an adenoma [9]. Overall, local recurrence rates of adenomas following TES vary depending on the specific study population but are reported to be 4–12 % [10–13]. Concern for increased recurrence risk in patients with larger adenomas (>3 cm) has been reviewed. Only positive margins were an independent predictor of recurrence [14].

Rectal adenomas can alternatively be removed by piecemeal endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR). Barendse et al. reviewed the recurrence and complications of resection of adenomas at least 2 cm in size that were on average 6.9 cm from the dentate line [15]. Multiple endoscopies were often necessary for complete tumor resection, and the early recurrence rate was substantially higher in the EMR group vs. TES (31 and 10.2 % respectively), a result of incomplete resection.

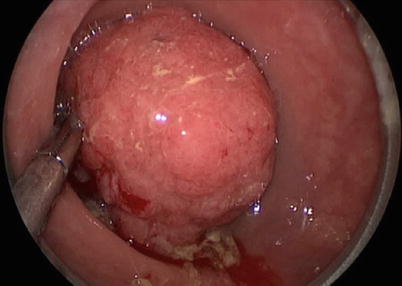

TES has been particularly successful at removing very large adenomas (>5 cm). Given the limited size of the rectoscope and concern over the size of the resulting rectal wall defect, resection of large sessile adenomas (>5 cm) was initially avoided. Schafer et al. in 2006 showed that removal of these large adenomas is safe in a group of 33 patients with lesions from 5 to 13 cm in largest diameter [10]. These patients were followed closely by proctoscopy given concern about possible suture line dehiscence. Fifteen percent of patients had some suture line insufficiency, which was managed nonoperatively. No episodes of sepsis occurred in the study group. One of the 15 patients required repair of the suture line by redo-TEM and ultimately underwent fecal diversion. A major advantage of TES is the ability to obtain a more complete and accurate tissue diagnosis since the entire rectal wall can be excised, thus curing early cancer contained in a polyp (Fig. 25.1).

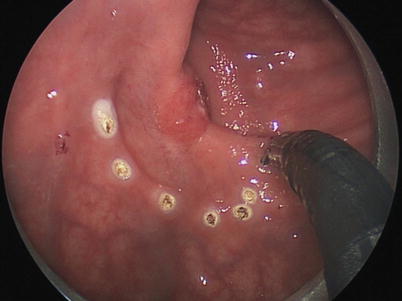

Fig. 25.1

Transanal endoscopic resection of a large villous lesion of the upper rectum

Rectal Cancer

The selection of appropriate patients with biopsy-proven early stage rectal cancer for TES can be challenging. Accurate staging aims to exclude patients who will not benefit from local resection alone. A malignant polyp on pathology shows invasion through the muscularis mucosae into the submucosa. Current NCCN guidelines state that transanal excision is appropriate in cases of cT1N0 tumors (Table 25.2) [16]. At this time, there is insufficient evidence to support routine local excision alone for radiologically staged T2N0 tumors or T1 tumors with adverse features as the risk of lymph node involvement and recurrence is significant. The incidence of positive lymph nodes in poor prognosis T1 rectal cancers is up to 13 % [17]. The recurrence risk for pT2 tumors after TES can be as high as 29.3 % in published series [18]. Serra-Aracil et al. in 2008 reported similar rates of recurrence and long-term survival for pT1N0 tumors with survival of 100 % at 2 years [19]. In a retrospective review at Memorial Sloan Kettering, the disease-specific survival was 87 % vs. 96 % at 5 years for transanal vs. radical rectal resection for pT1 cancers [20].

Table 25.2

National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN criteria for transanal excision of rectal cancer (2012)

<30 % circumference of bowel |

<3 cm in size |

Margin clear (>3 mm) |

Non-fixed, mobile lesion |

Within 8 cm of anal verge (unless TES platform used) |

T1 only |

Endoscopically removed polyp with cancer or indeterminate pathology |

No lymphovascular invasion or perineural invasion |

Well to moderately differentiated |

No evidence of lymphadenopathy on imaging |

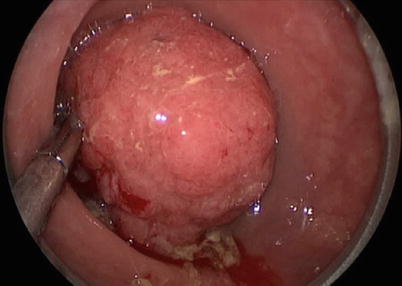

Risk factors for local recurrence after local excision of pT1 tumors have been evaluated extensively. Tumor size, submucosal invasion depth and tumor budding, lymphovascular invasion, and poorly differentiated histology were all significant predictive factors for locoregional failure after TEM for stage T1 cancer (Fig. 25.2) [21].

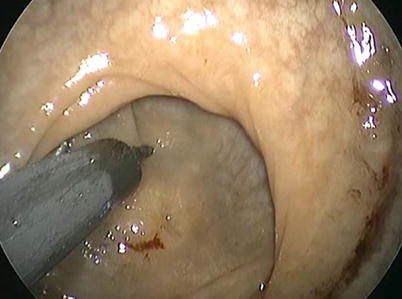

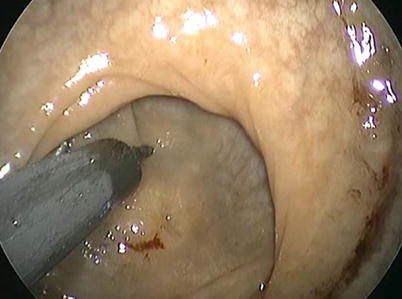

Fig. 25.2

Transanal endoscopic excision of a T1 rectal cancer of the mid-rectum

With a goal of increasing the pool of patients that can benefit from lower morbidity resection, surgeons have started to use TES on more advanced tumors, specifically T2 when combined with neoadjuvant therapy. A recent publication of 70 patients who underwent laparoscopic TME vs. TES for T2N0 rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy reported a local recurrence rate of 5.7 % vs. 2.8 % at 84 months following TES vs. laparoscopic TME which was not significant [22]. There were no significant differences in survival or complication rates.

Several ongoing trials are evaluating the short- and long-term oncologic outcomes of TES following tumor downstaging with neoadjuvant treatment for T2 and T3 rectal cancer. Garcia-Aguilar J et al. recently reported a series of 77 T2-staged rectal cancer patients who underwent neoadjuvant therapy followed by TES, which showed a 44 % pathologic complete response in the surgical specimen [23]. Kundel et al. reviewed a small sample of patients with locally advanced rectal cancer with pathologic complete response and retrospectively reviewed results of radical surgery and those that underwent local excision. The rate of regional disease was 3 % in radical excision groups suggesting that local excision may be sufficient in this circumstance for many patients [24]. Callender et al. published their results of 26 patients with T3 rectal cancer who underwent local excision (Kraske or TAE) after neoadjuvant therapy [25]. At a follow-up of approximately 4 years, there was no difference in disease-specific survival or the rate of local recurrence between local excision and TME.

Local recurrence is managed in a variety of ways depending on disease extent. Small studies have shown no difference in overall survival between patients undergoing salvage radical resection for locally recurrent pT1 rectal tumors originally treated with TES vs. those that underwent upfront radical surgery [26]. This suggests that there is little downside to proceeding with local resection as first-line therapy; however, adequate patient follow-up and surveillance protocols are necessary to identify local recurrence early. Local recurrence after TES should be treated by salvage radical resection and not TES re-excision as oncologic outcomes are better with radical resection.

Palliation of Rectal Cancer

Palliative strategies for locally advanced and symptomatic rectal cancer include: fecal diversion, stenting, surgical debulking or cryosurgery, embolization, and radiotherapy. TES provides an additional alternative method of palliating bleeding and obstructive complications of unresectable end-stage rectal cancer. Turler et al. in 1997 reported 29 cases of TES for rectal cancer palliation [27]. The main indications for TES were rectal bleeding and intestinal obstruction, which were relieved in all patients. One intra-abdominal perforation occurred. Hence, TES is a viable option for palliation. Certainly its role in this setting depends on patient-specific goals of care (Fig. 25.3).

Fig. 25.3

Palliative resection of a T2 mid-rectal cancer with TES in a patient with significant medical comorbidities precluding radical resection

Carcinoid Tumors

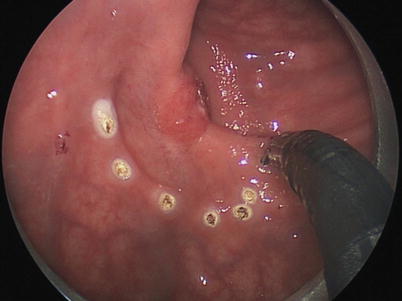

The incidence of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) has increased substantially over the past four decades owing to improved detection with screening endoscopy. The 5-year disease-specific survival for rectal carcinoids is 90.3 % [28]. In the SEER database, of 19,669 GI NETs, 6,796 were in the rectum, a majority of which were in the age group of 40–59 with nearly equal distribution to males and females. The primary treatment for rectal carcinoids is surgical resection. Of 202 patients in a multi-institutional study of outcomes in rectal carcinoids, 101 patients underwent local resection with 6 patients who underwent TES [29]. The presence of adverse histologic features such as lymphovascular invasion, invasion of the muscularis propria, and tumors larger than 1 cm requires resection of associated lymphatic tissue with mesorectal excision. The survival of T1 node-negative tumors is 100 %. Small tumors that are node negative can be removed by endoscopic means or transanal surgery alone. Endoscopic submucosal dissection has proven better than standard endoscopic polypectomy in for a complete histologic resection, but no comparison to TES has been made (Fig. 25.4).

Fig. 25.4

Resection of a 0.2 cm residual carcinoid tumor located in the upper rectum using TES

Retrorectal Tumors

Recently, groups have been expanding the role of TES to include resection of retrorectal tumors. Retrorectal tumors, often congenital in origin, are rare. Standard operative approaches have been either transabdominal or transcoccygeal. Resection of retrorectal lesions involves creating a defect in the posterior rectal wall to enter the retrorectal space. TES has now been used as a minimally invasive alternative [30, 31].

Rectovaginal and Rectourethral Fistulas

TES has recently been applied to repair of rectovaginal fistulas. D’Ambrosio et al. reviewed 13 patients who underwent repair of rectovaginal fistulas using a TES platform [32]. Fistulas were complications of transvaginal hysterectomy in seven patients, LAR in five patients, and radiotherapy in one patient. The median distance was 7 cm from anal verge (4–10 cm). This group included nine cases of failed transperineal repair, and four patients had multiple repairs with a combination of transabdominal, direct suture, or transperineal approaches. All 13 patients were previously diverted, and the recurrence rate following TES repair was only noted in 1/13 patients during the follow-up period. One of the operative pearls for this particular application was the use of vaginal packing to prevent leakage of CO2. Additionally, to keep the lesion in the appropriate field for ideal ergonomics, the authors recommend the patients be positioned prone. Importantly, TES provides excellent visualization of the fistula to allow for complete excision of the sclerotic tissue and flap coverage. This study group and the resultant success in patients who had already failed more conservative management attempts speak to the potential for TES-based repair.

Rectourethral fistula (occurring after radical prostatectomy) usually required major surgery, and TES has been explored as a minimally invasive alternative approach. To date, there have been a few case reports of rectourethral fistula repair. Similar to rectovaginal fistula repair, the surgical tenant is to excise the tract and perform flap closure of the rectal wall [33].

Anastomotic Leak

Anastomotic leak is a devastating complication in colorectal resections that often requires fecal diversion and abdominal washout. The cumulative morbidity associated with reoperation and stoma creation and subsequent stoma reversal is significant. TES has been used to manage early postoperative suture line dehiscence associated with leak in patients whose lesions were originally removed with TES. The use of this approach in patients undergoing standard rectal surgery seems ideal when technical expertise and clinical conditions are appropriate. So far this application has only been reported in a few case reports. Beunis et al. in 2008 reported a case of anastomotic leak following laparoscopic rectosigmoid resection with end-to-end stapled anastomosis for diverticular disease where the 1.5 cm anastomotic defect on CT was closed primarily using TES [34]. The patient did not require diversion or reoperation. Further studies on this approach are needed to determine whether this technique is safe and more widely applicable in the management of anastomotic leaks.

Pelvic Abscess

In colorectal surgery, pelvic abscesses pose a challenging problem. The utility of routine pelvic drainage remains controversial. Percutaneous drainage by interventional radiology is largely preferred over surgical drainage due to lower morbidity. TES has been described as an alternative minimally invasive method using transrectal drainage of low pelvic abscesses.

Martins et al. in 2011 described the use of TES to drain a pelvic fluid collection through a rectal stump after undergoing a Hartmann procedure for perforated rectal cancer [35]. In each case, a drain was placed through the rectal wall defect. This has been successfully applied in drainage of abscesses from a variety of causes.

Benign Strictures

Benign rectal strictures have now been successfully treated with stricturoplasty performed using TES. The most common cause of benign rectal strictures results from a prior colorectal anastomosis; however, additional etiologies have been treated as well including strictures caused by anal administration of medications or caustic enemas [11, 36]. Baatrup et al. reported a series of six patients who underwent resection of all fibrotic tissue, and five patients had clinical improvement.

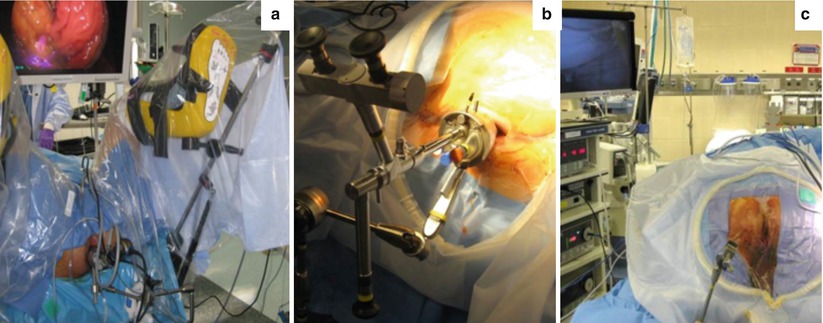

Advanced Applications (Advanced Resection and NOTES)

Transanal NOTES (natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery) have been an area of active investigation over the last few years. The TES platforms have shown to be versatile tools to gain endoscopic access to the peritoneal cavity, specifically to treat colorectal pathology. In addition, transanal specimen extraction during laparoscopic colorectal resection has been re-popularized with the use of TES techniques [37]. The potential benefits of transanal extraction derive from a smaller abdominal incision, hence reduced postoperative pain, wound infections, and incidence of incisional hernias [38, 39]. The theoretical concern of deep surgical site infection from utilizing the rectum as a means of specimen extraction has not borne out in the literature [40, 41].

The feasibility and safety of transanal NOTES colorectal resection is in its early phase of clinical evaluation. Several case reports and series on TES-approached TME performed with laparoscopic assistance have been published [42–46]. Laparoscopy serves two roles at this time – (1) to improve safety of transanal TME via retraction and visualization of at-risk pelvic structures and (2) to perform splenic flexure mobilization and mesenteric division. Perceived benefits include establishing a tumor-free distal margin and improved exposure compared to transabdominal approaches in the narrow pelvis. Ultimately, improvement in technique and equipment will hopefully eliminate the need for an abdominal incision and decrease morbidity. Long-term functional and oncologic outcomes of this novel approach are needed.

Patient Selection and Workup

TES can be successfully utilized in a wide array of rectal lesions. Patients of all ASA classes have been treated with TES, and efficacy and safety have been recently shown with patients with a BMI as high as 66 [47]. The exact preoperative workup is dependent on the lesion being treated; however, a number of principles hold for all patients. A complete history and physical inclusive of a digital rectal exam is performed to assess for the target lesion and its characteristics. The location, distance from the anal verge, and mobility should be documented. A complete colonoscopy is necessary, and preoperative biopsies should be taken to evaluate the pathology to be resected where indicated.

As an alternative method for local excision, TES does not substitute for radical rectal cancer resection when required in the management of resectable locally advanced rectal cancer. When used for early rectal tumors, careful selection using preoperative staging is essential to determine if TES is an adequate means of resection. Evaluation is performed to assess for local and distant disease. CT scans and endoscopic rectal ultrasound (ERUS) and/or pelvic MRI is used for tumor staging [48].

There are few hard contraindications to TES. Inability to dilate the anus to the appropriate size for the rectoscope (40 mm – for TEM platforms) or access port would make the procedure impractical. Although not routinely used in asymptomatic patients with good resting anal sphincter tone and squeeze on DRE, anal manometry may be selectively used in symptomatic patients with evidence of sphincter dysfunction. Patients with no preexisting sphincter dysfunction do experience decreased maximum anal resting pressure in the months following surgery; however, on 1-year follow-up, all patients return to baseline values, and quality of life is unaffected [49]. Additionally, the procedure is not recommended in patients with preoperative sphincter dysfunction due to concern for worsening incontinence. Other contraindications depend on the specific pathology being treated.

Basic Operative Setup and Instrumentation

For success with TES, the operative setup must be optimized. Preoperatively, patients either undergo a complete mechanical bowel preparation or enemas in order to minimize fecal soiling during transanal procedures. Procedures are performed under general anesthesia, and complete paralysis is essential to help maintain adequate pneumorectum. A Foley catheter is placed, and perioperative antibiotics should be provided in accordance with SCIP guidelines.

Patient positioning depends on the location of the lesion and the TES platform utilized. Rigid proctoscopy should be performed to evaluate the exact location of the lesion along the rectal wall and its distance to the anal verge. For rigid platforms including TEM or TEO that incorporate angled scopes and beveled platforms, the patient is positioned such that the target lesion is in the 6 o’clock position relative to the surgeon’s frame of reference. Thus the patient may be positioned in lithotomy, prone, or lateral decubitus for a lesion located along the posterior, anterior, or lateral rectal wall, respectively. For TAMIS platforms, lithotomy position is usually sufficient. Traditional lithotomy is most advantageous in this circumstance for operating comfort and anesthesia management. Proper positioning can be achieved using split-leg OR tables or stirrups if needed. If using stirrups (Fig. 25.5), the legs should be abducted and flexed to obtain good exposure and room for instrument manipulation. Steep Trendelenburg may be used, and careful padding of the patients is necessary.