The pathogenesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is multifactorial and varies from patient to patient. Disturbances of motor function in the small intestine and colon and smooth-muscle dysfunction in other gut and extraintestinal regions are prominent. Abnormalities of sensory function in visceral and somatic structures are detected in most patients with IBS, which may relate to peripheral sensitization or altered central nervous system processing of afferent information. Contributions from psychosocial disturbances are observed in patients from tertiary centers and primary practice. Proof of causation of symptom genesis for most of these factors is limited.

Although much research over the past decade has focused on pathogenic roles of inflammation or altered enteric microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), an enormous body of literature published beginning in the 1940s has extensively characterized traditional factors believed to be involved in the genesis of symptoms, including motor, sensory, central nervous system (CNS), and psychological abnormalities. More recent investigations using modern methods and studying IBS subsets well defined by validated clinical surveys have provided more detailed delineation of peripheral sensorimotor and central factors in relation to dominant symptom profiles. Because IBS is a heterogeneous disorder, it is likely that these distinct traditional factors participate to varying degrees in different patients. Furthermore, it is probable that many of the novel pathogenic inflammatory or infectious factors currently being studied also elicit symptoms by influencing gut motor and sensory function or information processing in the CNS.

Motor dysfunction

Disturbances of motor activity in several gastrointestinal and extraintestinal sites have been characterized in the different IBS subtypes; however, their roles in symptom pathogenesis for the most part are unproved. Several mediators have been proposed to contribute to motor dysfunction in IBS.

Small Intestinal Motor Abnormalities

Small intestinal motor function frequently is disturbed in IBS; however, the relevance of these defects to symptom induction is unproved. Small intestinal transit is generally reported as delayed in patients with constipation-predominant IBS (C-IBS) and accelerated in patients with diarrhea-predominant (D-IBS), although some large studies have not observed this association. On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), orocecal transit is accelerated in D-IBS, with associated reductions in terminal ileal diameter, possibly reflecting increased intestinal tone. Likewise, ileocolonic transit measured scintigraphically is accelerated postprandially in D-IBS.

Abnormalities of phasic small bowel contractile activity have been characterized in different subtypes of IBS. During fasting, a stereotypic pattern known as the migrating motor complex (MMC) cycles every 90 to 120 minutes to clear the proximal gut of undigested food residue. After consuming a caloric meal, small bowel motility converts to a fed pattern characterized by irregular phasic contractions that persist for up to 4 hours. Decreases in MMC amplitude and prolonged periodicity in patients with C-IBS and reductions in MMC cycle length in D-IBS have been reported. MMC propagation velocities reportedly are accelerated in IBS. Exaggerated jejunal fed responses, including increases in postprandial contractile frequencies, are seen in some patients with IBS although some studies have observed reduced fed amplitudes in C-IBS. In both subtypes, the duration of the fed pattern is shorter than in healthy controls. Retrograde duodenal and jejunal contractions are prominent in many patients with IBS, especially postprandially, and are reported to correlate with diarrhea in some cases. Discrete clustered contractions consisting of bursts of phasic contractions occurring every minute in the duodenum or jejunum, and prolonged propagated contractions consisting of intense ileal complexes that evacuate the ileum, may occur more commonly in patients with IBS than in healthy volunteers. In some individuals, clustered contractions and prolonged propagated small intestinal contractions are associated with symptom exacerbations. However, such clusters also are observed in other gut motor disorders such as chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction (CIP) and in healthy individuals, indicating that these patterns are not specific for IBS. The report of small bowel myenteric neuronal damage in individuals with severe IBS raises the possibility that some cases may fall along a spectrum that includes conditions with greater morbidity such as CIP. Small intestinal phasic contractile responses to other stimuli also may be modified in IBS. Cholecystokinin evokes high-amplitude ileal contractions in patients with D-IBS, whereas neostigmine induces discrete clustered contractions in both IBS subtypes. Conversely, reductions in duodenal motor responses to colonic distention are blunted in IBS.

Colonic Motor Abnormalities

Colonic motor abnormalities are prevalent in IBS, but correlate imperfectly with symptomatic bowel disturbances. In general, colon transit is accelerated in D-IBS and delayed in C-IBS. However, recent surveys observed abnormal colon transit in only 30% and 32% of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Symptoms correlating with colonic transit in IBS include abnormalities of stool form, frequency, and ease of passage.

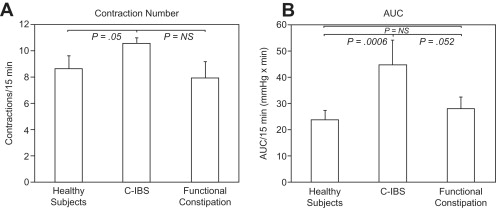

IBS has been associated with altered colonic myoelectric activity as well as phasic and tonic contractile function. In contrast to the stomach and small intestine, the colon shows no dominant myoelectric pacemaker activity. Rather, short spike bursts of 5 to 15 seconds underlie short-duration mixing contractions, whereas long spike bursts 15 to 60 seconds in duration are associated with contractions that show some propulsive characteristics. Early investigations observing abnormal 3-cycle-per-minute myoelectric rhythms in IBS were not confirmed by subsequent studies; such dysrhythmias instead were attributed to psychiatric factors in affected patients. High-amplitude propagated contractions (HAPCs) occurring infrequently throughout the day produce propulsive mass fecal movements, including those that precede defecation. In some older studies, no differences in phasic colonic motility were observed between patients with IBS and healthy controls. However, using wireless motility capsules, increases in colonic contractile activity were noted in C-IBS compared with healthy controls that are greater in the latter phases of colonic transit ( Fig. 1 ). Other recent investigations observe that patients with D-IBS have more frequent HAPCs versus healthy volunteers, whereas patients with C-IBS show fewer such complexes. In 1 investigation, 90% of HAPCs were associated with painful episodes. Others also have correlated HAPCs with pain reports. In normal volunteers, meal ingestion evokes increased myoelectric and motor activity, known as the gastrocolonic response, which peaks 20 to 30 minutes after eating. Patients with IBS may show exaggerated gastrocolonic responses lasting up to 3 hours, especially after high-fat meals. Rectal compliance has been reported to be reduced in some but not all studies in IBS. Colon tone in IBS measured by barostat methods is increased at baseline, is either unaffected or reduced after meal ingestion, and is blunted in response to colonic distention. One recent study observed a caloric dependence to abnormal tonic responses to meals in D-IBS, with reduced tone with 250-kcal meals and normalization of the response after consuming 1000 kcal of nutrients. As in the small bowel, IBS is associated with exaggerated colon motor responsiveness to exogenous stimulation, including abnormally prolonged and intense colonic contractions after colorectal balloon inflation, cholinergic stimulation, cholecystokinin administration, and colonic perfusion of deoxycholic acid. Recent investigations suggest evidence of dyssynergic defecation in some C-IBS cases, with affected patients having prolonged balloon expulsion times. This finding raises the possibility that many of the distal gut symptomatic and functional disturbances in IBS may relate to anorectal outlet dysfunction rather than colon wall abnormalities.

Motor Abnormalities in Other Regions

IBS also is associated with motor dysfunction of other gut and extraintestinal regions. Decreased lower esophageal sphincter pressures and abnormal esophageal body contractions are found in some patients with IBS. Delays in gastric emptying and gastric slow-wave dysrhythmias (tachygastria and bradygastria) and impaired slow-wave amplitude responses to meals are prevalent, especially in those with C-IBS and/or associated dyspepsia. In addition, gastric-emptying impairments have been correlated with small bowel motility disruption in IBS. Biliary tract abnormalities associated with IBS include impaired gallbladder emptying and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction with impaired sphincter relaxation in response to cholecystokinin stimulation. Outside the gastrointestinal tract, detrusor instability of the bladder and airway hyperreactivity to methacholine have been associated with IBS, suggesting the presence of a generalized dysfunction of smooth-muscle structures.

Possible Mediators of Motor Dysfunction

Several neurohumoral factors have been proposed to contribute to motor dysfunction in IBS. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]) pathways play important roles in modulating gut motility, including elicitation of the peristaltic reflex. Platelet-depleted plasma 5-HT levels are increased in those with D-IBS, especially in men, and correlate positively with increased sigmoid colon contractility, but are decreased in C-IBS. Likewise, the ratio of plasma 5-HT to 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, a 5-HT metabolite, is increased in D-IBS, whereas small bowel mucosal 5-HT levels are reduced in C-IBS. As another measure of altered 5-HT metabolism, women with IBS have abnormal plasma kynurenine to tryptophan ratios, which relate to symptom severity. Blood and tissue levels of other selected neuropeptides have been related to the presence of IBS. Patients with IBS show increased sigmoid colon and plasma cholecystokinin and vasoactive intestinal polypeptide levels and lower leptin levels. Neuropeptide Y levels in the plasma are lower in patients with D-IBS versus those with C-IBS; urinary levels of the melatonin metabolite 6-sulfatoxymelatonin are reduced in C-IBS, especially in men. Despite the observed associations, none of these neurohumoral factors has proved to be causative of any symptom profile in IBS.

Altered visceral sensory activity

As with motor abnormalities, alterations in visceral and somatic perception are prevalent in IBS but have uncertain roles in inducing the different symptoms of this disorder. Abdominal sensations are mediated by afferent pathways activated by stimuli acting on mechanoreceptors (which detect changes in tension), mesenteric nociceptors (which detect painful stimuli), and chemoreceptors (which sense osmolarity, temperature, and pH). Information from these receptors is transmitted by afferent pathways to the brain, where conscious perception occurs. Hypersensitivity may present as hyperalgesia (an increase in pain intensity reporting for a given painful stimulus compared with a control population), allodynia (reporting of pain from a stimulus not considered painful by healthy individuals), hypervigilance (increased attention to noxious stimulation compared with controls), and exaggerated pain referral patterns (perception of pain outside the normal anatomic sites normally activated in healthy individuals). Hypersensitivity may result from peripheral sensitization of spinal dorsal horn neurons or abnormal CNS processing of afferent information projecting from the gut.

Visceral Sensory Dysfunction

Some patients with IBS experience normal physiologic events, not normally perceived by healthy individuals, as being uncomfortable or painful. Examples of this phenomenon include the observations that patients with IBS can sense different phases of the MMC, feel discomfort during passage of food residue from the ileum to the cecum, and experience pain during prolonged propagated contractions and discrete clustered contractions in the small intestine and HAPCs in the colon.

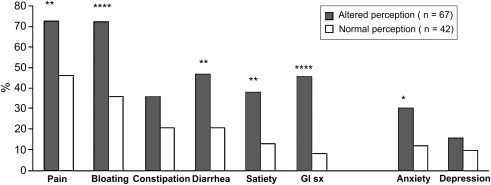

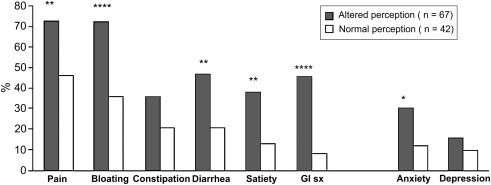

Exaggerated perception is inducible by visceral stimulation in substantial percentages of patients with IBS. Most studies report that pain is experienced at lower volumes or pressures of rectal or ileal balloon inflation in patients with IBS than healthy controls, an effect not caused by altered visceral wall properties. Some investigators report that hypersensitivity is specific for abrupt phasic distentions and that perception of a slow ramplike inflation is normal in IBS. The degree of heightened sensation has been noted to be greater in women than men. Increases in sensitivity to distention of more proximal gut regions also are observed in some patients with IBS, including the esophagus, stomach, and small bowel. Those with symptoms referable to multiple gut regions seem to have generalized hypersensitivity, whereas those with more localized symptoms seem to have heightened sensation in more restricted locations. Hypersensitivity to ingestion of chili capsules, mucosal electrical and thermal stimulation, and intestinal lipid perfusion has been shown, suggesting that hyperalgesia is not specific for mechanoreceptor-activated pathways. Evidence supporting a relation of visceral sensory abnormalities to symptom severity is conflicting, with some studies showing a positive correlation and others observing little or no association ( Fig. 2 ). Not all patients have a heightened perception of distention. Whereas individuals with D-IBS commonly have reduced thresholds for sensing luminal balloon inflation, some patients with C-IBS, hard stools, and no fecal urgency show reduced perceptual responses to distending stimuli. A recent prospective study observed that only 20% of patients with IBS had increased sensation to luminal distention, whereas 16% showed reduced rectal sensation. Patients with IBS also may show atypical pain referral patterns during gut distention, experiencing pain diffusely in the abdomen, back, shoulders, or chest. One group has reported that 94% of patients with IBS show visceral sensory abnormalities when alterations in abdominal pain referral patterns are coupled with hypersensitive perception of rectal distention, but in light of more recent data to the contrary, this finding is not universally accepted as a biomarker for IBS.

As with studies of motor dysfunction, abnormalities of sensory activity may be prominent under stimulated conditions. Colonic hypersensitivity is augmented by ingestion of cold water and high-fat nutrient meals, especially in D-IBS. Repeated sigmoid colon distentions elicit prominent hyperalgesia as well as abnormal pain referral patterns in IBS, perhaps secondary to spinal dorsal horn neuronal sensitization. Furthermore, repetitive inflations at levels less than those needed to elicit perception can lead to increased contractile activity in IBS. Rectal glycerol perfusion enhances sensitivity to distention.

Some investigators attribute exaggerated perception in IBS to psychological factors based on studies showing similar responses in patients with IBS and healthy controls when perceptual tests designed to minimize emotional influences were used. Other investigations suggest that patients with IBS show a stronger tendency to report sensations as painful or negative during distention versus controls. These findings have led some to propose that patients with IBS may show either peripheral hypersensitivity to distention or hypervigilance resulting from psychological dysfunction. However, some studies comparing perception of true versus sham distentions in healthy controls and patients with IBS show no effect of psychological bias.

Somatic Sensory Dysfunction

It remains controversial whether sensory dysfunction in IBS is restricted to the gut or is generalized to include hypersensitive responses in somatic structures. In some studies, responses to cutaneous electrical and thermal stimulation, including cold-water immersion, are similar in patients with IBS, healthy controls, and patients with organic disease. Patients with IBS have shown reduced responsiveness to somatic pressure and electrical stimulation compared with patients with fibromyalgia. Conversely, other investigations observed increased perception of calf and forearm heat pain in patients with IBS, impaired tolerance of cold-water stimulation in patients with functional disorders, and increased generalized somatic sensation in patients with IBS with coexisting fibromyalgia. In addition, 3 subgroups were distinguished based on severity of somatic hypersensitivity in 1 report. Several investigations have further characterized somatic sensory defects in IBS. In 1 study, hypersensitivity to thermal stimulation correlated positively with visceral hypersensitivity to distention. Increased thermal sensitivity is more prominent in lower extremities sharing viscerosomatic convergence with the colon. In another investigation, combining cold-pressor stimulation of the foot with rectal distention increased rectal perception in IBS. Other groups report that noxious visceral stimulation is perceived as more unpleasant than somatic stimulation in IBS, whereas degrees of unpleasantness to the 2 stimuli are similar in patients with coexistent IBS and fibromyalgia.

Possible Mediators of Sensory Dysfunction

Several factors have shown associations with sensory dysfunction in IBS, suggestive of possible pathogenic roles in symptom induction. Local factors may contribute to hypersensitivity. Rectal sensitivity in patients with IBS is reduced by topical lidocaine administration, emphasizing the importance of sodium channels in this response. Nerve-fiber sodium channels were decreased in rectal biopsy specimens from patients with hypersensitivity. However, the observation that placebo jelly reduces perception of rectal distention more than distention without any topical treatment shows the importance of psychological factors as well. Mice with knockouts of the acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) show impaired visceral sensitivity. ASIC3 pathway defects have also been observed in animal models of IBS.

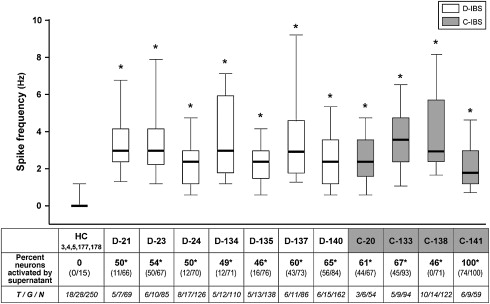

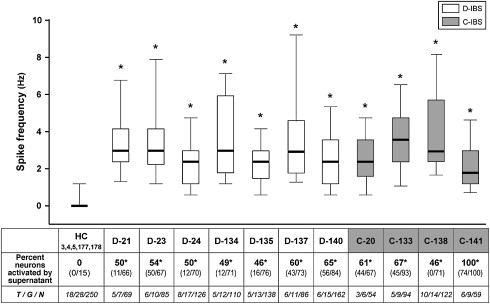

Neurohumoral abnormalities have been identified in patients with IBS and in animal models of visceral hypersensitivity. In D-IBS, heightened rectal sensation correlates with numbers of enterochromaffin cells in rectal biopsy specimens. In rats, intraperitoneal or intracerebroventricular 5-HT 2B antagonist treatment blunts visceral hypersensitivity. Increases in substance-P immunoreactive nerve fibers have been identified in colon biopsies from patients with IBS. Most unmyelinated C-fibers mediating perception of noxious gut stimuli express transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptors, which are activated by both capsaicin and cannabinoids. Involvement of TRPV1 receptors is reported in animal models of visceral hypersensitivity. Furthermore, studies of patients with IBS with rectal hypersensitivity show increases in TRPV1-expressing fibers in the colon. Conversely, TRPV1 antagonists decrease colonic sensitivity to distention in rats given neonatal acetic acid perfusion and TRPV1 receptor knockout mice show analgesic responses to thermal stimulation. In healthy humans, the cannabinoid receptor agonist dronabinol increases perception of painful colonic distention. In animal models, cannabinoid CB 1 receptor antagonists increase rectal sensitivity to distention. Protease activated receptors (PARs) may participate in heightened visceral sensitivity in IBS. Supernatants from colonic biopsy specimens of patients with IBS sensitize cultured sensory neurons and induce hyperalgesia, an effect blocked by inhibitors of serine protease and not observed in sensory neurons not expressing PAR-2 receptors. Intracolonic PAR-2 agonist perfusion initiates hypersensitivity to distention. In another study, a PAR-4 receptor agonist reduced responsiveness to colonic distention and blunted visceromotor responses to PAR-2 and TRPV4 agonists. In other recent investigations, submucosal neuronal spike discharges elicited by supernatants from colonic biopsies of patients with IBS are inhibited by histamine antagonists, 5-HT 3 antagonists, and protease inhibition ( Fig. 3 ). Visceral hypersensitivity in rats induced by maternal separation is associated with reduced glial excitatory amino acid transporter-1 and can be counteracted by spinal administration of riluzole, an agent that activates glutamate reuptake. Inhibition of cystathione-β-synthase decreases the abdominal withdrawal reflex to colonic distention in rats. Expression of the P 2×3 purinergic receptor protein is increased in some rat models of visceral hypersensitivity. Visceromotor responses to mechanical distention are reduced in P 2×3 +/− and −/− mice. Visceral hypersensitivity can be reversed by antagonists of P 2×1 , P 2×3 , and P 2×2/3 subtypes. The importance of any of these neurohumoral pathways in gut sensory dysfunction in IBS is undefined.

Altered visceral sensory activity

As with motor abnormalities, alterations in visceral and somatic perception are prevalent in IBS but have uncertain roles in inducing the different symptoms of this disorder. Abdominal sensations are mediated by afferent pathways activated by stimuli acting on mechanoreceptors (which detect changes in tension), mesenteric nociceptors (which detect painful stimuli), and chemoreceptors (which sense osmolarity, temperature, and pH). Information from these receptors is transmitted by afferent pathways to the brain, where conscious perception occurs. Hypersensitivity may present as hyperalgesia (an increase in pain intensity reporting for a given painful stimulus compared with a control population), allodynia (reporting of pain from a stimulus not considered painful by healthy individuals), hypervigilance (increased attention to noxious stimulation compared with controls), and exaggerated pain referral patterns (perception of pain outside the normal anatomic sites normally activated in healthy individuals). Hypersensitivity may result from peripheral sensitization of spinal dorsal horn neurons or abnormal CNS processing of afferent information projecting from the gut.

Visceral Sensory Dysfunction

Some patients with IBS experience normal physiologic events, not normally perceived by healthy individuals, as being uncomfortable or painful. Examples of this phenomenon include the observations that patients with IBS can sense different phases of the MMC, feel discomfort during passage of food residue from the ileum to the cecum, and experience pain during prolonged propagated contractions and discrete clustered contractions in the small intestine and HAPCs in the colon.

Exaggerated perception is inducible by visceral stimulation in substantial percentages of patients with IBS. Most studies report that pain is experienced at lower volumes or pressures of rectal or ileal balloon inflation in patients with IBS than healthy controls, an effect not caused by altered visceral wall properties. Some investigators report that hypersensitivity is specific for abrupt phasic distentions and that perception of a slow ramplike inflation is normal in IBS. The degree of heightened sensation has been noted to be greater in women than men. Increases in sensitivity to distention of more proximal gut regions also are observed in some patients with IBS, including the esophagus, stomach, and small bowel. Those with symptoms referable to multiple gut regions seem to have generalized hypersensitivity, whereas those with more localized symptoms seem to have heightened sensation in more restricted locations. Hypersensitivity to ingestion of chili capsules, mucosal electrical and thermal stimulation, and intestinal lipid perfusion has been shown, suggesting that hyperalgesia is not specific for mechanoreceptor-activated pathways. Evidence supporting a relation of visceral sensory abnormalities to symptom severity is conflicting, with some studies showing a positive correlation and others observing little or no association ( Fig. 2 ). Not all patients have a heightened perception of distention. Whereas individuals with D-IBS commonly have reduced thresholds for sensing luminal balloon inflation, some patients with C-IBS, hard stools, and no fecal urgency show reduced perceptual responses to distending stimuli. A recent prospective study observed that only 20% of patients with IBS had increased sensation to luminal distention, whereas 16% showed reduced rectal sensation. Patients with IBS also may show atypical pain referral patterns during gut distention, experiencing pain diffusely in the abdomen, back, shoulders, or chest. One group has reported that 94% of patients with IBS show visceral sensory abnormalities when alterations in abdominal pain referral patterns are coupled with hypersensitive perception of rectal distention, but in light of more recent data to the contrary, this finding is not universally accepted as a biomarker for IBS.

As with studies of motor dysfunction, abnormalities of sensory activity may be prominent under stimulated conditions. Colonic hypersensitivity is augmented by ingestion of cold water and high-fat nutrient meals, especially in D-IBS. Repeated sigmoid colon distentions elicit prominent hyperalgesia as well as abnormal pain referral patterns in IBS, perhaps secondary to spinal dorsal horn neuronal sensitization. Furthermore, repetitive inflations at levels less than those needed to elicit perception can lead to increased contractile activity in IBS. Rectal glycerol perfusion enhances sensitivity to distention.

Some investigators attribute exaggerated perception in IBS to psychological factors based on studies showing similar responses in patients with IBS and healthy controls when perceptual tests designed to minimize emotional influences were used. Other investigations suggest that patients with IBS show a stronger tendency to report sensations as painful or negative during distention versus controls. These findings have led some to propose that patients with IBS may show either peripheral hypersensitivity to distention or hypervigilance resulting from psychological dysfunction. However, some studies comparing perception of true versus sham distentions in healthy controls and patients with IBS show no effect of psychological bias.

Somatic Sensory Dysfunction

It remains controversial whether sensory dysfunction in IBS is restricted to the gut or is generalized to include hypersensitive responses in somatic structures. In some studies, responses to cutaneous electrical and thermal stimulation, including cold-water immersion, are similar in patients with IBS, healthy controls, and patients with organic disease. Patients with IBS have shown reduced responsiveness to somatic pressure and electrical stimulation compared with patients with fibromyalgia. Conversely, other investigations observed increased perception of calf and forearm heat pain in patients with IBS, impaired tolerance of cold-water stimulation in patients with functional disorders, and increased generalized somatic sensation in patients with IBS with coexisting fibromyalgia. In addition, 3 subgroups were distinguished based on severity of somatic hypersensitivity in 1 report. Several investigations have further characterized somatic sensory defects in IBS. In 1 study, hypersensitivity to thermal stimulation correlated positively with visceral hypersensitivity to distention. Increased thermal sensitivity is more prominent in lower extremities sharing viscerosomatic convergence with the colon. In another investigation, combining cold-pressor stimulation of the foot with rectal distention increased rectal perception in IBS. Other groups report that noxious visceral stimulation is perceived as more unpleasant than somatic stimulation in IBS, whereas degrees of unpleasantness to the 2 stimuli are similar in patients with coexistent IBS and fibromyalgia.

Possible Mediators of Sensory Dysfunction

Several factors have shown associations with sensory dysfunction in IBS, suggestive of possible pathogenic roles in symptom induction. Local factors may contribute to hypersensitivity. Rectal sensitivity in patients with IBS is reduced by topical lidocaine administration, emphasizing the importance of sodium channels in this response. Nerve-fiber sodium channels were decreased in rectal biopsy specimens from patients with hypersensitivity. However, the observation that placebo jelly reduces perception of rectal distention more than distention without any topical treatment shows the importance of psychological factors as well. Mice with knockouts of the acid-sensing ion channel 3 (ASIC3) show impaired visceral sensitivity. ASIC3 pathway defects have also been observed in animal models of IBS.

Neurohumoral abnormalities have been identified in patients with IBS and in animal models of visceral hypersensitivity. In D-IBS, heightened rectal sensation correlates with numbers of enterochromaffin cells in rectal biopsy specimens. In rats, intraperitoneal or intracerebroventricular 5-HT 2B antagonist treatment blunts visceral hypersensitivity. Increases in substance-P immunoreactive nerve fibers have been identified in colon biopsies from patients with IBS. Most unmyelinated C-fibers mediating perception of noxious gut stimuli express transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) receptors, which are activated by both capsaicin and cannabinoids. Involvement of TRPV1 receptors is reported in animal models of visceral hypersensitivity. Furthermore, studies of patients with IBS with rectal hypersensitivity show increases in TRPV1-expressing fibers in the colon. Conversely, TRPV1 antagonists decrease colonic sensitivity to distention in rats given neonatal acetic acid perfusion and TRPV1 receptor knockout mice show analgesic responses to thermal stimulation. In healthy humans, the cannabinoid receptor agonist dronabinol increases perception of painful colonic distention. In animal models, cannabinoid CB 1 receptor antagonists increase rectal sensitivity to distention. Protease activated receptors (PARs) may participate in heightened visceral sensitivity in IBS. Supernatants from colonic biopsy specimens of patients with IBS sensitize cultured sensory neurons and induce hyperalgesia, an effect blocked by inhibitors of serine protease and not observed in sensory neurons not expressing PAR-2 receptors. Intracolonic PAR-2 agonist perfusion initiates hypersensitivity to distention. In another study, a PAR-4 receptor agonist reduced responsiveness to colonic distention and blunted visceromotor responses to PAR-2 and TRPV4 agonists. In other recent investigations, submucosal neuronal spike discharges elicited by supernatants from colonic biopsies of patients with IBS are inhibited by histamine antagonists, 5-HT 3 antagonists, and protease inhibition ( Fig. 3 ). Visceral hypersensitivity in rats induced by maternal separation is associated with reduced glial excitatory amino acid transporter-1 and can be counteracted by spinal administration of riluzole, an agent that activates glutamate reuptake. Inhibition of cystathione-β-synthase decreases the abdominal withdrawal reflex to colonic distention in rats. Expression of the P 2×3 purinergic receptor protein is increased in some rat models of visceral hypersensitivity. Visceromotor responses to mechanical distention are reduced in P 2×3 +/− and −/− mice. Visceral hypersensitivity can be reversed by antagonists of P 2×1 , P 2×3 , and P 2×2/3 subtypes. The importance of any of these neurohumoral pathways in gut sensory dysfunction in IBS is undefined.

Gut sensorimotor dysfunction in bloating and distention

Evidence suggests that gut motor and sensory dysfunction as well as somatic factors participate in the sensation of bloating and the sign of visible distention in IBS. Bloating commonly is reported by patients with either D-IBS or C-IBS, but demonstrable distention detected by techniques such as impedance plethysmography is more prominent in those with C-IBS, who often have associated hard stools and delays in small intestinal or colonic transit.

Insight into the pathogenesis of gas and bloating has been provided by studies involving intestinal gas perfusion. In healthy humans, jejunal delivery of physiologic gas mixtures mimicking venous gaseous concentrations produces steady-state flow with little distention and few symptoms. An older study using an argon washout method observed that total intestinal gas volumes in IBS are normal. However, abnormal retrograde gas reflux patterns were noted in some individuals, suggestive of transit defects. More recent jejunal gas perfusion studies observed pathologic gas retention in IBS associated with symptom development and increased abdominal girth. Using radiolabeled xenon scintigraphy to localize sites of gas retention, patients with functional bloating show selective delays in gas transit in the small intestine. This finding is supported by the observations that jejunal but not ileal gas perfusion produces gas retention, and duodenal lipid perfusion selectively delays gas transit in the small bowel in an exaggerated fashion in patients with IBS. However, in a recent study, patients with IBS showed impaired gas clearance from the proximal colon during retrograde gas perfusion into the rectum, indicating participation of colonic motor defects as well. Patients with IBS with objective distention also show increases in anal pressures and prolonged rectal balloon expulsion times, suggesting a role for anorectal outlet dysfunction as a contributor to gaseous symptoms in some cases. However, others have observed rapid transit of solid-liquid meals in some patients with IBS with bloating, indicating heterogeneity in symptom pathogenesis.

The importance of perception is emphasized by observations from perfusion studies that, for similar degrees of gas retention, patients with bloating develop greater symptoms compared with healthy controls. Furthermore, patients with bloating but no distention show heightened perception of gas perfusion, whereas those with bloating and distention show normal to reduced perceptual responses. Patients with IBS with bloating also show heightened sensation of rectal distention, whereas those with bloating plus distention show reduced perception, which indicates generalized gut hypersensitivity.

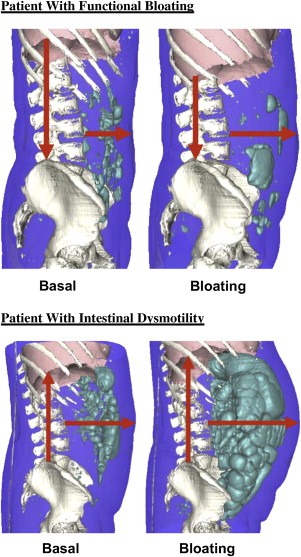

Other contributors to bloating and distention in IBS include abnormal activities of the diaphragm and abdominal somatic musculature. In a computed tomography (CT) study in patients with bloating, severe distention episodes were associated with exaggerated diaphragmatic descent. Supporting a role for somatic muscle factors in IBS, patients with manometrically documented small intestinal dysmotility showed greater gas retention during jejunal gas perfusion than patients with IBS despite having similar symptoms and increases in abdominal girth. Likewise using a CT method to quantify luminal gas, investigators observed increased gas retention with intestinal dysmotility associated with abdominal wall protrusion and cephalad diaphragmatic excursion, whereas those with functional bloating showed no increase in gas volume but showed protruded abdominal walls with caudad diaphragmatic movements ( Fig. 4 ). Recent rectal gas perfusion studies reported increases in perception in IBS and functional bloating, which were associated with changes in external and internal oblique muscle contraction, indicating an interaction of visceral and somatic musculature in production of gaseous symptomatology.