Total Gastrectomy and Esophagojejunostomy

Andrew M. Lowy

Hop S. Tran Cao

Total gastrectomy, with subsequent restoration of alimentary tract continuity in the form of esophagojejunostomy, is an operation that can result in significant postoperative metabolic and nutritional derangements. For this reason, care must be taken to properly select and optimize the right candidate for this procedure.

The most common indication for total gastrectomy is an attempt at curative resection for gastric adenocarcinoma located within the fundus or body of the stomach. While some authors have advocated the use of subtotal gastrectomy for tumors limited to the proximal third of the stomach, this approach offers no survival advantage while being associated with greater perioperative morbidity and mortality. Instead, we reserve subtotal gastrectomies for tumors of the gastric antrum, for which distal gastrectomy has been well established as the procedure of choice as long as a generous proximal margin (5 to 6 cm) can be obtained. Linitis plastica, a diffuse form of gastric adenocarcinoma involving the entire stomach, may theoretically be treated with total gastrectomy. However, cancer cells in this disease process tend to infiltrate far beyond the visible tumor, and clear resection margins are often not achievable; surgery is therefore rarely used to treat this lethal disease.

Less common indications for total gastrectomy include the following:

Other neoplasms of the stomach such as gastric neuroendocrine tumors, leiomyosarcomas, or lymphosarcomas

Palliation for hemorrhagic, obstructive, or perforated gastric tumors or intractable pain. With advances in endoscopic and angiographic technologies, the need for surgical intervention in a palliative role has diminished.

Zollinger–Ellison syndrome that has failed other attempts at symptom control. In a patient with Zollinger–Ellison, every effort should be made to identify and remove the primary gastrinoma lesion and to debulk metastatic disease when possible. Medical management should include the use of proton pump inhibitors and octreotide, a somatostatin analogue. However, when ulcer diathesis persists despite these efforts, a total gastrectomy can be offered for symptomatic relief.

Contraindications to total gastrectomy in the setting of gastric cancer include the presence of disseminated disease with peritoneal seeding and/or liver metastases and local invasion of the tumor into the aorta, celiac axis, or vena cava. On the other hand, direct extension of the tumor into adjacent structures, including the transverse colon, middle colic vessels, pancreatic body and tail, spleen, or left lobe of the liver, does not preclude resection; in this circumstance, en bloc resection of the stomach with the involved organ segment is warranted.

In planning a total gastrectomy for gastric cancer, a thorough staging work-up should be undertaken. Obtaining tissue diagnosis is paramount and is achieved via upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. This modality allows visual inspection and sampling of the tumor; biopsies should be taken at multiple sites from the ulcer edges and not the base, which may be necrotic and yield false-negative results. Endoscopic ultrasound may be of value in assessing the depth of tumor invasion and nodal status, particularly in patients enrolling in neoadjuvant treatment studies.

A high-quality computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is obtained to look for metastatic disease and assess the extent of tumor invasion. Imaging of the chest is especially helpful in patients with proximal tumors when the possibility of thoracotomy is contemplated.

For the same reason, preoperative pulmonary function tests may be indicated for those patients with high proximal lesions, while a mechanical bowel preparation should be considered if the transverse colon is involved by the tumor and en bloc resection is anticipated.

Patients with gastric carcinoma often present with advanced disease and are nutritionally depleted as a result of obstructive symptoms or early satiety. Therefore, their nutritional status should be assessed and optimized if possible.

Basic blood tests, including liver function tests and coagulation parameters, are taken.

Pertinent Anatomy

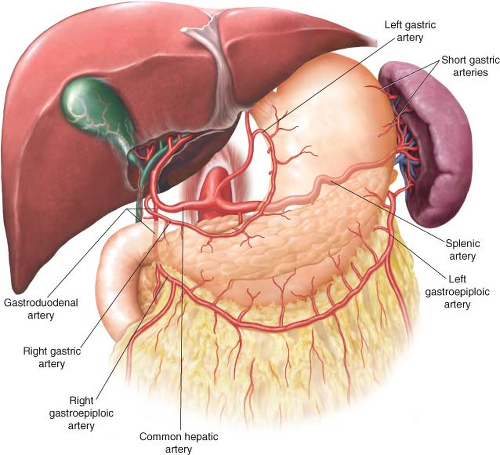

Two major anatomical concepts should be mastered when approaching total gastrectomy. First, the blood supply to the stomach and, by extension, its lymphatic drainage must be well understood (Fig. 19.1). The stomach is supplied by an extensive vascular network formed by four major arteries stemming directly or indirectly from the celiac axis, the main vascular branch to the embryologic foregut. The lesser curvature of the stomach is vascularized by the left gastric artery, a main branch of the celiac axis, and the right gastric artery, most often a branch of the hepatic artery. The vascular supply to the greater curvature consists of the left gastroepiploic artery, a branch of the splenic artery, and the right gastroepiploic artery, which most often stems from the gastroduodenal artery. The greater curvature also receives some blood supply from short gastric arteries originating from the splenic artery near the splenic hilum.

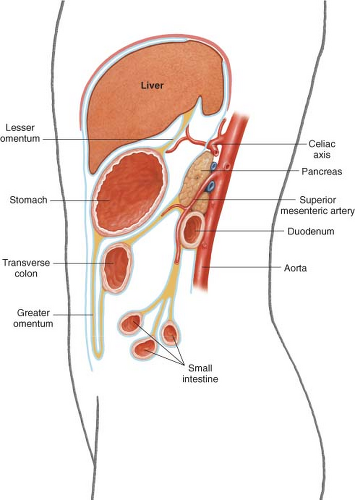

It is also important to understand the three-dimensional relationship of the stomach with its surrounding organs (Fig. 19.2). The stomach is attached to the liver by the lesser omentum, also known as the gastrohepatic ligament. The greater omentum hangs off its greater curvature and attaches to the transverse colon along an avascular plane. The transverse mesocolon lies behind the stomach and reaches the pancreas, a retroperitoneal organ that sits directly posterior to the stomach. A tumor of the stomach may therefore encroach or directly invade any of these structures, as well as the left lobe of the liver, or the spleen.

Positioning

The patient is placed on the table in the supine position, with the bed in slight reverse Trendelenburg position. The abdomen and chest are widely prepped and draped. The arms can be abducted to allow for attachment of the Bookwalter retractor. A Foley catheter is inserted and appropriate prophylactic antibiotics administered. The patient is provided both pharmacologic and mechanical thrombophylaxis.

Incision/Exposure

When the indication for total gastrectomy is gastric cancer, we routinely start by performing a staging laparoscopy. This procedure has been shown to spare between 23 and 37% of patients with CT-occult metastatic disease an unnecessary laparotomy by detecting small peritoneal or liver deposits. Particular attention is paid to the liver surfaces, omentum, and peritoneum in the pouch of Douglas.

Even following a negative laparoscopy, we initially prefer a limited midline epigastric incision extending from the xiphoid process that allows for exploration and confirmation of resectability. Once this is accomplished, the incision is extended to or just past the umbilicus to afford adequate exposure. If the tumor involves the proximal stomach and extends to the distal esophagus, a combined thoracoabdominal approach may be necessary. A Bookwalter retractor is placed; the lateral segment of the left lobe of the liver is mobilized and is retracted anteriorly and to the right with a fan retractor.

Surgical Technique

The first step of the operation is to perform a thorough exploration of the abdominal cavity to confirm resectability.

To rule out metastatic disease, the liver is thoroughly assessed and palpated, and the peritoneal surface, especially in the pouch of Douglas, is carefully examined for tumor deposits.

Next, the stomach is evaluated to determine the extent of local invasion. This is accomplished by manually inspecting the anterior surface of the stomach. The posterior aspect of the stomach is palpated after accessing the lesser sac to ensure that the tumor does not invade into the aorta, celiac axis, or vena cava. Such a finding should be rare as preoperative imaging is highly accurate in assessing these relationships. As previously mentioned, direct extension into the transverse colon or its mesenteric root, the pancreas, the spleen, or the left lobe of the liver does not contraindicate total gastrectomy; in such a situation, en bloc resection is indicated, although prognosis for these patients is poor.

Once the potential for surgical cure has been verified, total gastrectomy can be carried out. While there continues to be significant controversy surrounding the optimal extent of lymph node dissection, our practice is to perform a modified D2 lymphadenectomy that removes lymph nodes along the celiac, splenic, and hepatic arteries in addition to the perigastric lymph nodes. Routine splenectomy and distal pancreatectomy are not performed, as they offer no survival advantage while accounting for the majority of D2 dissection-associated complications reported in the literature. With this in mind, total gastrectomy is begun along the greater curvature and omentum.

The transverse colon is isolated by taking down the hepatic and splenic flexures. It is then dissected away from the greater omentum along the avascular plane. The colon is then retracted inferiorly while the omentum is lifted up to expose the lesser sac, including the anterior surface of the pancreas and the transverse mesocolon.

The greater omentum is traced up on the left side until the left gastroepiploic vessels are identified, ligated, and divided. The splenic hilum is examined; if it is involved with the tumor, a splenectomy is performed. Otherwise, the short gastric vessels are taken down as close to the spleen as possible. Vessel or tissue sealing devices can be used to complete this division rapidly with good hemostasis; likewise, they are a good option to complete the omental dissection described above.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree