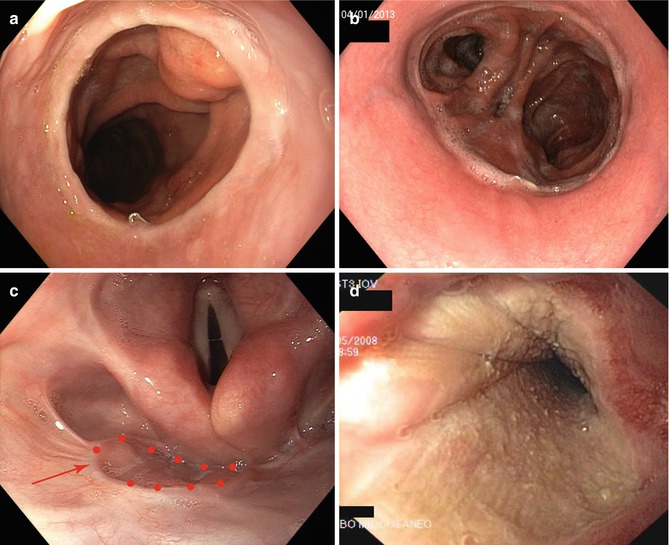

Fig. 4.1

Patients with esophageal/cardia cancer treated at the Veneto Centre for esophageal disease

4.3 Complication After Surgery and Surveillance Endoscopy

In the anastomotic context, endoscopy is able to reveal complications which can appear in the first postoperative days (such as fistulae and interposed viscera necrosis) or in the long term (such as stenosis, esophagitis, and recurrence in cancer patients due to not complete resection or relapse) (Fig. 4.2).

Fig. 4.2

Esophageal anastomotic variants: intrathoracic esophagogastric anastomosis (gastric pull-up) (a), esophagojejunal anastomosis (b), pharyngo-colonic anastomosis (highlighted by the red arrow) (c), and musculocutaneous graft (d)

4.3.1 Fistula

Fistula is the most serious complication due to diagnostic difficulty, clinical management, and mortality. It appears in the early postoperative period, usually within 10 days but in some rare cases even later. It always causes a worsening of the patient’s condition, ranging from prolonged hospitalization to a life-threatening condition. When appearing in the very early stages (second or third postoperative day), it implies a particularly serious condition as the visceral contents can easily spread to the mediastinum; in this case it is associated with significant high mortality (P = 0.013) [12]. In our case records, we have distinguished three types of fistulae (Table 4.1).

Table 4.1

Fistulas classification employed at our department

1 | Subclinical (radiologic) | |

2a | Minor without borders ischemia | Affects less than ¼ of the esophageal circumference and mainly caused by a technical error; the borders are well vascularized |

2b | Minor with ischemic borders | Affects less than ¼ of the esophageal circumference; may be related to an insufficient vascularization of the graft or a prolonged hypotension during or immediately after surgery |

3a | Major with necrosis of borders | Affects more than ¼ of the esophageal circumference; related to an important non-transitory vascular insufficiency; necrosis of the anastomotic borders |

3b | Major with extensive necrosis of the graft | Affects more than ¼ of the esophageal circumference with an extensive wall necrosis of the graft |

In the literature, the global incidence of esophageal fistula goes from 4 to 14.3 % and represents the most important postoperative factor influencing mortality; the mortality linked to this complication ranges from 16.7 to 50 %, in relation to local factors (fistula gravity, associated necrosis of the tubule), general factors (associated diseases, vascular pathologies, dermatosclerosis, etc.), and the number of surgical procedures [13, 14]. There are many factors playing a role in determining the development of fistulae: they could be due to the adopted techniques such as the type of anastomosis (mechanical or manual) or the tension caused by a too short tubing (if taken to the neck) or due to functional factors leading to ischemia of the gastric tubing, which can depend on either general causes (systemic vascular pathologies) or local causes (a tight diaphragm passage, previous radiotherapy treatment, or the type of viscera used—the ileal and colon segments are the more sensitive whereas the stomach seems to be less sensitive).

Thanks to new techniques, above all the mechanical suturer, a technical error while making an anastomosis is rare to observe today. A more common problem is the ischemia of the mobilized viscera which, to a certain degree, happens in all patients but rarely leads to the inability of healing. Therefore, when a combination of ischemia and mechanical stress has a negative effect on the anastomosis, a fistula can occur. According to some authors, but without clear scientific evidence, radiotherapy may represent another risk factor, especially for an anastomosis at the neck.

A meta-analysis by Biere et al. [15] on four randomized studies analyzing anastomotic risk factors, showed that fistula incidence was significantly higher for cervical anastomoses in respect to intrathoracic ones (2–30 % vs 0–10 % P = 0.03), even if the thoracic ones generally have a more complicated course. The author explains that this difference could be due to the vascular suffering caused by tubing or to the manual technique that is used for performing a cervical anastomosis. On the contrary, in another study by Kayani et al. [16] examining 47 published articles, no clear evidence was found concerning a higher incidence for cervical anastomoses, but the studies comparing the two types of anastomoses are few, with a low number of cases, and they are not standardized concerning surgery approaches, anastomosis techniques, and the neo-adjuvant therapy.

Analyzing the gastric tube preparation, Collard showed 1 % fistulae with the whole stomach vs 7.9 % with tubular stomach while, regarding the intrathoracic interposition, Shu observed less fistulae with the tubular stomach (5.5 % vs 9.3 % (P < 0.05)) compared to the whole viscera [17]. Age does not appear to be a risk factor if vascular diseases are not involved; Tapias observed anastomotic leakage in 4.8 % of patients <70 years 4.8 % in 70–80 age and 0 % < 80 years (P = 0.685).

Regarding seriousness of fistulae, Price and colleagues [18] report a global incidence of 11 % with a superior incidence of neck anastomoses (6/34, 21 %) against intrathoracic (16/268, 5.9 %) but without significant difference regarding the percentage of more serious fistulae with partial or extended necrosis of the viscera (4.8 % vs 4.8 %). In our global experience, we have had 7.3 % of fistulae of which only 1.1 % were serious, with a significant reduction to 5.9 % over the last decade. The level of the anastomosis was decisive for the development of a slight fistula (11.3 % cervical vs 4.3 % thoracic (P = 0.0001)), as it was also for the type of viscera interposed at the cervical level, even if not significant (colon 16.8 % vs stomach 10.7 % (P = NS)).

Whenever an interpositioning is performed with the colon or the jejunum, the lower anastomosis also needs to be monitored as it is the area where, in our experience, there is a fistula incidence of 4.7 % (12/255: 8 slight 4 serious).

Appearance of necrosis has a low rate (1.1 %) and here as well a significant difference between cervical and thoracic levels is to be found (22/774 vs 6/1,468 (P < 0.001)). Our study did not observe a correlation with comorbidities like cirrhosis, diabetes, obesity, nephropathy, or arteriopathy as shown by the following data:

Cirrhosis (1/48 (2.1 %) in patients with cirrhosis vs 27/2,194 (1.7 %); P = 0.46)

Diabetes (3/159 (1.9 %) in patients with diabetes vs 25/2,083 (1.2 %); P = 0.44)

Obesity (0/21 in obese patients vs 28/222 (1.3 %); P = 0.99)

Nephropathy (1/55 (1.8 %) in patient with nephropathy vs 27/2,187 (1.2 %); P = 0.50)

Arteriopathy (2/93 (2.2 %) in patients with arteriopathy vs 26/2,149 (1.2 %); P = 0.32)

Anastomotic fistula diagnosis may be difficult [19]. Normally surgeons control the anastomosis with a digestive tube on the seventh day before feeding starts and the control is mandatory in the presence of risk factors like a difficult anastomosis or a serious blood pressure decrease in the early postoperative period or a suspected septic state. These are the conditions to be aware of as the anastomotic fistula or tubular necrosis has to be diagnosed as early as possible in order to quickly start the appropriate treatment.

In suspect cases, as the first approach, a digestive tube and, if positive, a CT scan should be requested; even if 50 % of fistulae are not detected with these exams, they are the basis for the next endoscopic exam. Endoscopy is the only exam able to show suffering in the interposed viscera or am anastomotic leakage: it should be performed by an expert endoscopist using a weak insufflation and, possibly, a hood placed on the tip to enable the detection of the suture line. While performing the retroversion (which is a very risky maneuver), the gastric side of the anastomosis and any eventual vascular problem or necrosis should be described. This procedure allows to determine the presence a critical anastomosis before fistulization in order take the correct measures that often can be done only to delay the refeeding (Figs. 4.3 and 4.4).

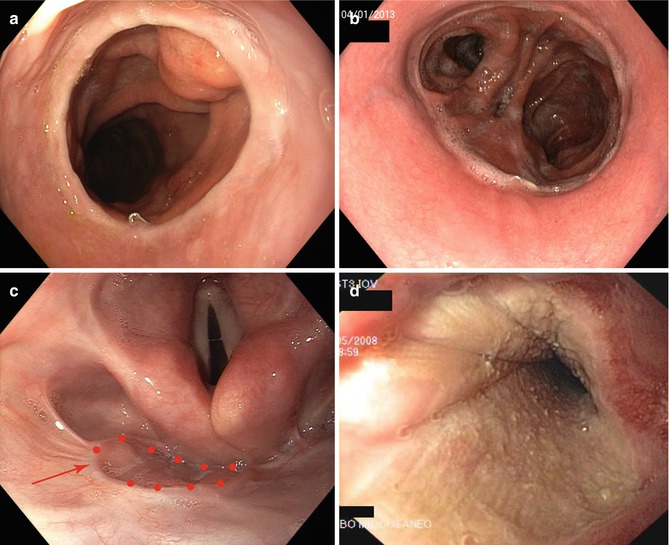

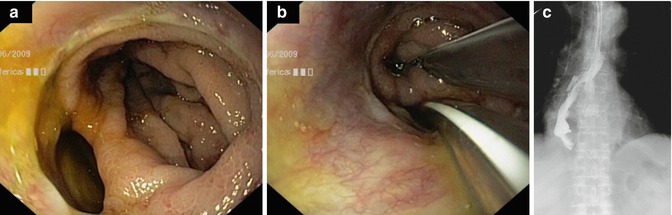

Fig. 4.3

Large anastomotic fistula without necrosis (a), conservative treatment by positioning one tube in the stomach and the other one in the mediastinum (b), and X-ray control after 10 days of parenteral nutrition (c)

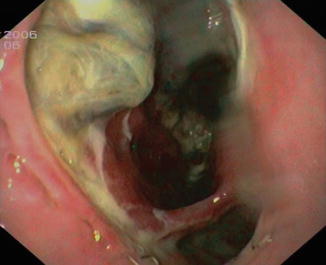

Fig. 4.4

Anastomotic leakage with necrotic tissue

Once the diagnosis has been done, the monitoring of the clinical process of the viscera can be done by daily endoscopic controls if a conservative treatment has been decided. In fact there is not always an indication to surgical treatment even when there is a major fistula, especially if the patient’s general condition is not serious and if the disassembling of the anastomosis is technically difficult.

In our experience, if there is no extended necrosis; we always prefer a conservative treatment which includes internal drainage placed endoscopically in the fistula and a gastric tube. We monitor the clinical state carefully and the viscera with daily endoscopic exams, if necessary, and surgery is performed only if the clinical parameters get worse.

4.3.2 Stenosis

The incidence of benign anastomotic stenosis after an esophagectomy and gastric tube reconstruction reported is 10–15 %. They are associated to fistula recovery, ischemia, or the surgical technique used. However, in some cases, these are not the causes, and gastroesophageal reflux is the determinant (Fig. 4.5).

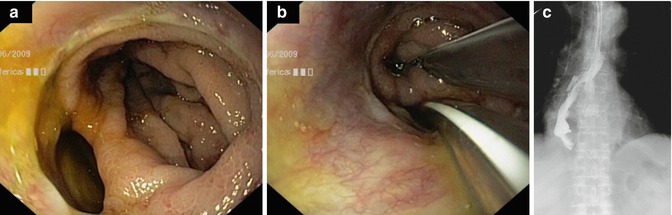

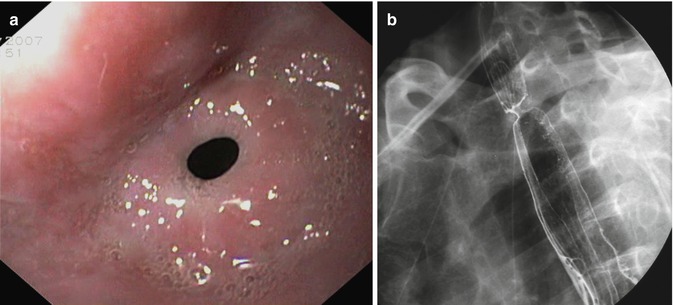

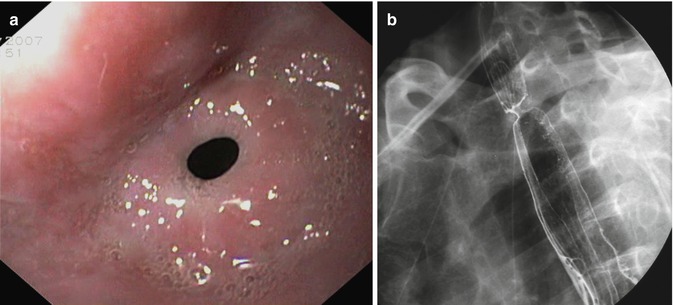

Fig. 4.5

Tight anastomotic stenosis: endoscopic (a) and radiological vision (b)

In a Dutch study, carried out on 80 patients who did not complain of an anastomotic fistula in the postoperative period, reflux weighs heavily upon the development of a stenosis (13 % vs 45 %, P = 0.001): another factor is the use of a 25-mm caliber mechanical suturer compared to a 28 mm or 31 mm one, with the first mentioned the risk was 2.9 times higher [20].

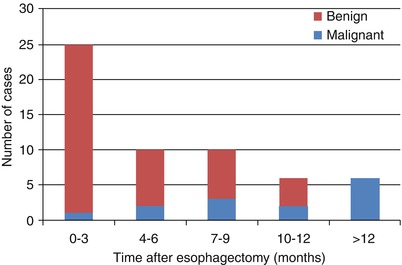

In Sutcliffe’s study [21] 177 patients were followed for 3 years; 48 (2.7 %) developed a stenosis which was the result of an anastomosis tightening enough to provoke clinical symptomatology; 40 were benign and 14 were malignant (6 benign developed into malignant ones). Of those which developed within 3 months, 96 % were benign; within 1 year, the benign were 83 %. All cases of stenosis present after 1 year (6/6) were caused by tumor recurrence (Fig. 4.6).

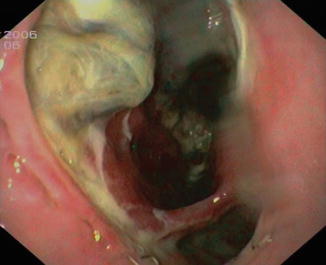

Fig. 4.6

Timing of anastomotic strictures after esophagectomy (Reproduced with permission from [21])

Due to the fact that the principal cause was a fistula, the authors recommended early dilatation after healing, even without symptoms, to prevent its possible development [22].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree