The Trunk Muscles

We need to become familiar with all of the muscles affecting the lower trunk – the area between the ribcage and the pelvic bones. At the front and sides of the trunk are the four principal abdominal muscles, at the back the spinal muscles and, at the base of the trunk, and actually within the pelvic bones themselves, the pelvic floor muscles. We are also concerned with the hip muscles because, as we have seen, hip, pelvic, and lumbar motion is intimately linked.

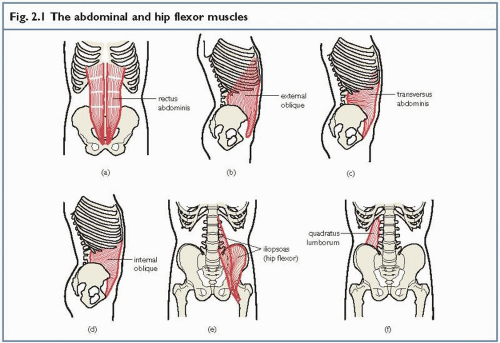

In the centre of the abdomen is the rectus abdominis (see fig. 2.1a). This muscle runs from the lower ribs to the pubic region, forming a narrow strap. It tapers down from about 15 cm (6 inches) wide at the top to 8 cm (3 inches) wide at the bottom. The muscle has three fibrous bands across it at the level of the tummy button, and above and below this point. The rectus muscle on each side of the body is contained within a sheath; the two sheaths merge in the centre line of the body via a strong fibrous band called the linea alba. This region

splits during pregnancy to allow for the bulk of the developing child (see chapter 14).

splits during pregnancy to allow for the bulk of the developing child (see chapter 14).

At the side of the abdomen there are two diagonal muscles, the internal oblique (see fig. 2.1d) and the external oblique (see fig. 2.1b). The internal oblique attaches to the front of the pelvic bone and a strong ligament in this region. From here it travels up and across to the lower ribs and into the sheath covering the rectus muscle. The external oblique has a similar position, but lies at an angle to the internal oblique. The external oblique begins from the lower eight ribs and travels to the sheath covering the rectus muscle and to the strong pelvic ligaments. The fibres in the centre of the muscle are travelling diagonally, but those right on the edge are travelling vertically and will assist the rectus muscle in its action.

Underneath the oblique abdominals lies the transversus abdominis (see fig. 2.1c). This attaches from the pelvic bones and tissue covering the spinal muscles and travels horizontally forwards to merge with the sheath covering the rectus muscle.

Keypoint

The surface (superficial) muscles of the abdomen are the rectus abdominis (centre) and external oblique (side).

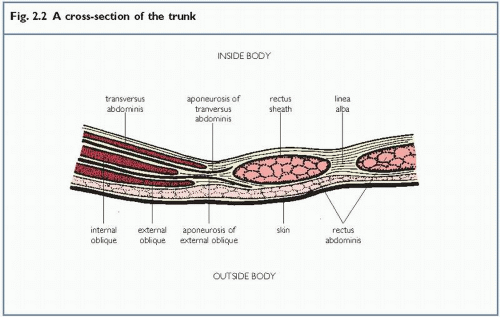

Fig. 2.2 shows a cross-section of the trunk. In the centre you can see the rectus muscle surrounded by connective tissue called the rectus sheath. This sheath from the two neighbouring muscles joins in the centre to form the linea alba. At the side of the trunk you can see the three distinct layers of muscles, from the

inside out transversus, internal oblique and external oblique.

inside out transversus, internal oblique and external oblique.

At the side and back of the trunk, the quadratus lumborum muscle is also important (see fig. 2.1f). It is positioned between the pelvis and ribcage, and has an inner and outer portion. The inner portion is attached directly to the spine, so is important for stability. The outer portion has a tendency to get tight and painful during backpain.

There are several hip muscles, but the most important in relation to abdominal training is the iliopsoas (see fig. 2.1e). This is, in fact, two muscles (the psoas and iliacus) attached to a single point on the hip. The psoas muscle attaches to various parts of the lumbar spine including the vertebra itself and the spinal disc – hence its importance to the spine. The iliacus muscle attaches from the inner surface of the pelvis and has no direct effect on the spine. Both muscles travel forwards to the inner/upper part of the thigh bone (femur). The iliopsoas works to lift the thigh upwards (hip flexion) or the trunk downwards towards the thigh when this bone is fixed (sit-up action). The muscle also causes compression of the spine when it is worked hard in, for example, a straight leg lifting action lying on the back.

Keypoint

The iliopsoas muscle of the hip affects the spine by (i) lifting the trunk in a sit-up action; and (ii) causing lumbar compression forces during a straight leg lifting motion.

When we are performing abdominal exercises to enhance core stability we must also be aware of the pelvic floor muscles (see fig. 14.2, page 174). These attach to the inside of the pelvis and form a sort of sling running from the tailbone (coccyx), at the back, to the pubic bone (crotch) at the front. The muscles from each side of the body join in the middle, and the front and back passages (vagina, urethra and anus) are formed within the pelvic floor muscles. These openings are controlled by rings of muscle called sphincters which lie in the pelvic floor. The pelvic floor muscles are important for both men and women. They are essential for core stability following back pain and may be damaged in women during pregnancy and in men following prostate surgery (see chapter 14).

Keypoint

The pelvic floor muscles are important in both men and women.

All these muscles work together and so, in any action involving the abdomen, most of the muscles will be active to a certain extent. In a sit-up action, the iliopsoas works and the upper portion of the rectus is emphasised. In pelvic tilting the lower portion of the rectus and the outer fibres of the external oblique are used. Twisting actions involve the oblique abdominals, while the transversus acting with the obliques pulls the tummy in tight. This muscle is used in coughing and sneezing as well. Together with the obliques, the outer portion of the quadratus is important for side bending actions and also pulls on the lower ribs when breathing deeply. The inner portion is next to the spine and helps to support it in actions which tend to pull you sideways. The quadratus is therefore important to core stability when carrying an object in one hand – for example, a shopping basket or case. After pregnancy (see chapter 14), following certain types of lower back pain, after some types of surgery and in very obese individuals, the pelvic floor muscles reduce their tone and people can sometimes lose control of the sphincters and

dribble urine. For this reason, regaining control of the pelvic floor is important and can be achieved at the same time as re-educating the deep muscle corset (transversus and internal oblique). As we shall see (on page 174), the pelvic floor muscles are also integral to the creation of pressure which forms the ‘abdominal balloon’, an important process in developing core stability.

dribble urine. For this reason, regaining control of the pelvic floor is important and can be achieved at the same time as re-educating the deep muscle corset (transversus and internal oblique). As we shall see (on page 174), the pelvic floor muscles are also integral to the creation of pressure which forms the ‘abdominal balloon’, an important process in developing core stability.

Summary

The rectus muscle bends the trunk and lifts the tail when lying on the back.

The obliques twist the spine.

The transversus pulls the tummy in tight.

The quadratus lumborum muscle stiffens the spine when a force tries to bend the spine sideways.

The iliopsoas flexes the hip and compresses the lumbar spine.

The pelvic floor muscles can be re-educated at the same time as core stability.

How the trunk muscles act for core stability

There are several methods by which the trunk muscles can make the trunk more solid and contribute to core stability.

The abdominal balloon

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree