Posterior compartment prolapse can be thought of as a relaxation or separation of the tissues of the rectovaginal septum and perineal body. This article reviews the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and surgical management of rectoceles and relaxed vaginal outlet. With proper treatment, a continued active lifestyle and improved quality of life usually can be restored; however, this result requires a thorough understanding of pelvic anatomy and pathophysiology and experience in performing the appropriate surgical procedures.

Posterior compartment prolapse can be thought of as a relaxation or separation of the tissues of the rectovaginal septum and perineal body. Common symptoms include difficulty with defecation and, less commonly, sexual dysfunction. A continued active lifestyle and improved quality of life usually can be restored; however, this result requires a thorough understanding of pelvic anatomy and pathophysiology and experience in performing the appropriate surgical procedures. This article reviews the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and surgical management of rectoceles and relaxed vaginal outlet.

Pelvic floor physiology

The main support for the pelvic viscera is provided by a group of muscles collectively called the levator ani. An intact pelvic floor allows the pelvic and abdominal viscera to rest on the levator ani, significantly reducing the tension on the supporting fascia and ligaments. These pelvic ligaments are not true ligaments and are condensations of the endopelvic fascia that covers the pelvic structures. The pelvic floor musculature and the pelvic ligaments work together to provide support to the pelvic floor structures. Most of the weight of the pelvic viscera is supported by the levator ani, whereas the pelvic ligaments stabilize these structures in position much like water supports a ship’s weight and moorings keep a ship from straying away from the dock. When the levator ani is damaged, excessive force is placed on the ligaments, predisposing the patient to pelvic prolapse.

The posterior vaginal wall in the midvagina is supported centrally and laterally by rectovaginal fascia, which is attached to the fascia of the levator ani musculature. These attachments prevent the rectum from prolapsing into the vagina, causing a rectocele. The distal vagina is attached firmly to the surrounding structures, including the urethra and symphysis pubis anteriorly, levator ani laterally, and perineal musculature posteriorly. Damage to the perineal musculature by childbirth or surgery is a common cause for rectoceles and a relaxed vaginal outlet.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of posterior vaginal wall relaxation often can be linked to multiparity, advanced age, hormonal insufficiency, obesity, neurogenic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, connective tissue abnormalities, or strenuous physical activity; however, pelvic relaxation can occur in young, inactive, nulliparous patients, and a single cause rarely can be implicated. The exact incidence of relaxed vaginal outlet is unknown because not all patients are symptomatic; however, the condition is believed to be common.

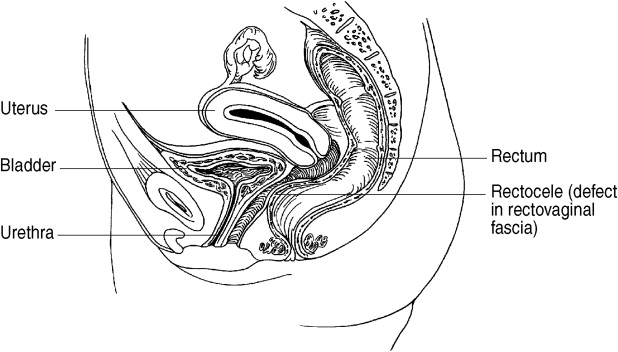

A rectocele is a prolapse of the rectum into the vagina through a damaged rectovaginal septum ( Fig. 1 ). The most likely cause of rectocele formation and perineal relaxation is childbirth, as these conditions are essentially confined to parous women. In some cases, a relaxed outlet may be caused by an inadequate or incompletely healed episiotomy that was performed at the time of childbirth.

The most important fascia within the rectovaginal septum is Denonvilliers fascia, which is fused to the inner layer of the posterior vaginal wall and is believed to be disrupted at the caudal and lateral attachments at the perineal body during childbirth. In some cases, enterocele and rectocele formation occur together, especially if the patient has had a previous hysterectomy. Although a high rectocele may be only distinguished from an enterocele at the time of surgery, a rectocele often forms a pocket just proximal to the anal sphincter. This pocket is where stool can become trapped and can cause the typical symptoms of straining or the need for digital manipulation (splinting) to facilitate bowel movements.

Perineal body relaxation, a separate and distinct entity from a rectocele, usually is manifested by a large vaginal opening and is repaired at the same time as a rectocele. Because the levator ani are attached at the perineal body, strengthening of the perineal body by perineorrhaphy tightens the levator plate, improving the overall degree of pelvic relaxation.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of posterior vaginal wall relaxation often can be linked to multiparity, advanced age, hormonal insufficiency, obesity, neurogenic dysfunction of the pelvic floor, connective tissue abnormalities, or strenuous physical activity; however, pelvic relaxation can occur in young, inactive, nulliparous patients, and a single cause rarely can be implicated. The exact incidence of relaxed vaginal outlet is unknown because not all patients are symptomatic; however, the condition is believed to be common.

A rectocele is a prolapse of the rectum into the vagina through a damaged rectovaginal septum ( Fig. 1 ). The most likely cause of rectocele formation and perineal relaxation is childbirth, as these conditions are essentially confined to parous women. In some cases, a relaxed outlet may be caused by an inadequate or incompletely healed episiotomy that was performed at the time of childbirth.

The most important fascia within the rectovaginal septum is Denonvilliers fascia, which is fused to the inner layer of the posterior vaginal wall and is believed to be disrupted at the caudal and lateral attachments at the perineal body during childbirth. In some cases, enterocele and rectocele formation occur together, especially if the patient has had a previous hysterectomy. Although a high rectocele may be only distinguished from an enterocele at the time of surgery, a rectocele often forms a pocket just proximal to the anal sphincter. This pocket is where stool can become trapped and can cause the typical symptoms of straining or the need for digital manipulation (splinting) to facilitate bowel movements.

Perineal body relaxation, a separate and distinct entity from a rectocele, usually is manifested by a large vaginal opening and is repaired at the same time as a rectocele. Because the levator ani are attached at the perineal body, strengthening of the perineal body by perineorrhaphy tightens the levator plate, improving the overall degree of pelvic relaxation.

Clinical presentation

The most common symptoms of a rectocele and relaxed outlet are constipation, which is nonspecific, and splinting, which is the need to place fingers on the posterior wall of the vagina to empty the bowels. In general, the larger the relaxation, the more severe the symptoms; however, Caps reported that 8% of symptomatic patients had mild relaxation. Other presenting symptoms may include perineal pain or sexual dysfunction; however, these symptoms are uncommon. Dyspareunia has been reported after a surgical repair in up to 30% of cases. The current incidence is less than 10%, because the older method of repair, which plicated the levator musculature, is now seldom used.

Indications

Rectocele repair is rarely required unless the patient has an anatomic defect and typical constipation symptoms. At my institution, I occasionally repair isolated large rectoceles that cause significant pressure symptoms and repair large rectoceles as a part of an overall vaginal vault prolapse reconstruction. It is difficult to justify postoperative dyspareunia to fix a small, asymptomatic rectocele or perineal body. Some investigators believe that not performing these repairs at the time of an incontinence procedure or hysterectomy may cause undue pressure on other areas of the pelvic floor, possibly necessitating additional surgery at a later date. This has not been my experience, however.

Physical examination

In many cases, a rectocele easily may be seen when the patient quickly bears down; however, if this position is maintained for only a short period of time, some rectoceles (and an enterocele or vault prolapse) may not be appreciated. Unlike a cystocele evaluation, the rectum cannot be filled, and a digital inspection may be required for further evaluation, especially if the patient is unable to strain sufficiently. A surgical plan should be made before going to the operating room. This evaluation cannot be performed adequately under anesthesia, because the patient is unable to strain and the pelvic muscles are relaxed. The posterior vaginal wall is examined by placing the lower blade of the Graves speculum against the anterior vaginal wall. A bulging of the posterior vaginal wall with straining may be an enterocele or a rectocele ( Fig. 2 ). Descent of the vaginal wall at the level of the hymen or below is usually a rectocele, whereas prolapse near the apex may be an enterocele. After a hysterectomy, descent of the vaginal apex with straining indicates a lack of vault support. The perineal body, which lies between the vagina and anus, should be evaluated for structural integrity. A lax perineal body usually is manifested by an enlarged introitus or a flattening of the perineum with descent on straining.