Traditionally, in the lay, legal, and medical communities, death has been determined by an irreversible cessation of cardiac and respiratory function. The concept of brain death emerged in the 1960s as a response to the ability to resuscitate individuals and mechanically maintain cardiac and respiratory function. The terms brain death and cardiac death are employed in this chapter because of their widespread use and familiarity. These terms are not ideal and may be a source of confusion and distress in the lay community and among donor families because of understandable but unsubstantiated concern that brain-dead donors are not truly dead. The terms death determined by neurologic criteria and death determined by cardiorespiratory criteria are preferable.

Diagnosis of Brain Death

Most organ donors have severe brain injury and present to the hospital with a low Glasgow Coma Scale score (

Table 4.2). Most deceased organ donors are brain dead. Proper diagnosis of brain death is essential to the organ donation process

and to maintaining public trust and acceptance of organ donation from brain-dead organ donors. Among the lay public, there is often a troubling confusion between the diagnosis of brain death and that of a persistent vegetative state. The criteria for diagnosis and declaration of brain death are well described (

Table 4.3) and require irrefutable documentation. They include a known cause of brain injury, irreversibility, and absence of cerebral and brainstem function, including apnea.

The diagnosis of brain death should be made by a physician who is independent of the transplantation team and thus free of conflict of interest. Ancillary testing is not mandated but may include electroencephalography, conventional angiography, radionuclide angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, computed tomographic angiography, transcranial Doppler, and somatosensory evoked potentials. Indications for pursuit of ancillary testing include toxic drug levels, inconclusive apnea testing, normal neuroimaging, inability to complete a clinical examination, and chronic CO

2 retention.

Diagnosis of Cardiac Death

The term

donation after cardiac death (DCD) is preferred to the term

non-heart-beating donor (NHBD) because of the parallel to the more common

donation after brain death. Before the acceptance of criteria for the declaration of brain death, all deceased donor organs were recovered from patients with cardiac arrest. With the broad acceptance of brain death criteria and the development of multiorgan recovery, the use of DCD organs decreased substantially because

of the risks associated with ischemic damage. The organ donor shortage has led to a reevaluation of this policy.

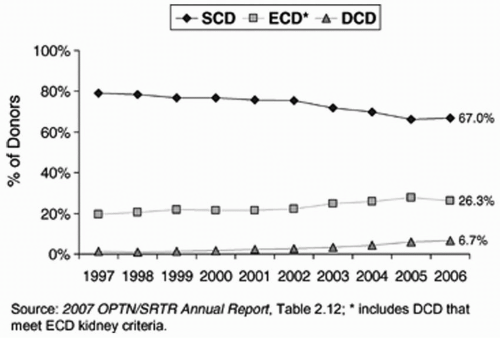

There has been a steady increase in the fraction of DCD donors in the United States (see

Fig. 4.1). There are four so-called Maastricht categories of DCD donors (

Table 4.4). Category I and II DCD donors, also referred to as

uncontrolled donors, are pulseless and asystolic after adequate but failed attempts at resuscitation. Some trauma centers have developed protocols to minimize ischemia in these circumstances by rapid placement of intravenous cannulas to cool the organs after death has been declared. The option to donate is preserved until the family can be informed of the death and then counseled by the organ procurement staff. If consent to donate is obtained, the organs are recovered quickly to prevent further ischemic injury.

Uncontrolled DCD is the most common form of DCD in Spain and Japan. In the United States, DCD is usually category III or “controlled.” These donors are comatose, irreversibly brain damaged, and respirator dependent, but are not brain dead by strict definition. In these circumstances, the decision to withdraw supportive care is made by the family and primary medical team, and appropriate consent for organ donation is obtained after the decision to withdraw support. Ventilator support is discontinued either in the operating room or in an intensive care unit, cardiac function is monitored, and death is pronounced by standard cardiac criteria after a predetermined (usually 5-minute) period of asystole. Organ recovery then proceeds expeditiously. The organ recovery team plays no part in the diagnosis of death or medical management of the patient before asystole. Maastricht category IV DCD donors are also known as “crashing donors,” who have often become hemodynamically unstable en route to organ recovery after a diagnosis of brain death.

It has been estimated that if DCD protocols were maximized, the supply of deceased donor organs could increase considerably. DCD is associated with an increased rate of delayed graft function, but long-term graft survival is similar to that of brain-dead donors. It is critical that protocols for DCD be ethically sound, respect the feelings of donor families and medical staff, and avoid any appearance of conflict of interest. As of 2007, all organ procurement organizations (OPOs) and transplant centers in the United States must develop and comply

with protocols to facilitate recovery of organs by DCD. The model elements of DCD protocols are summarized by Steinbrook (see “

Selected Readings”).