Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common disorder that has been shown to aggregate in families and to affect multiple generations, but not in a manner consistent with a major Mendelian effect. Relatives of an individual with IBS are 2 to 3 times as likely to have IBS, with both genders being affected. To date, more than 100 genetic variants in more than 60 genes from various pathways have been studied in a number of candidate gene studies, with several positive associations reported. These findings suggest that there may be distinct, as well as shared, molecular underpinnings for IBS and its subtypes.

As discussed in articles elsewhere in this issue, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic disorder characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort and diarrhea and/or constipation that can be associated with altered gastrointestinal motility and visceral sensation. The chronicity of IBS symptoms and the lack of a cure or effective treatments result in loss of work and school productivity and impaired personal and health-related quality of life. Patients, their relatives, and friends frequently ask difficult questions, such as why they in particular developed IBS. Although diet, psychological factors, infection, and gut flora may attenuate IBS symptoms, there is no simple answer to this question. As other family members may concurrently have bowel disturbances, the role of genes in disease development—and the sense of personal destiny it invokes—is somewhat intuitive, easy to accept, but also difficult to refute with facts or objective findings arguing the contrary.

Great advances have been made in genetics in recent years. As the efficiency, ease, and cost of genotyping has decreased, our understanding of DNA sequence, structure, and function has improved dramatically. Previously, laboratory-based study of the human genome was often restricted to known genes and coding exon regions and study of a handful of genetic variants. Now, high-throughput technology allows genotyping of thousands to a million genetic markers across the genome, and sequencing of nearly the entire [coding] human genome is now possible. Furthermore, advances in data storage and analysis of these large quantities of data has led to the discovery of susceptibility loci for several diseases including, notably, Crohn’s disease. These amazing scientific strides have led many to believe that “virtually every human ailment, except perhaps trauma, has some basis in our genes.” ( www.genome.gov ). This premise has appealed to many IBS researchers, and several have commenced in trying to identify an IBS gene or set of genes.

Despite the acceptance by some that genes may cause—or at least contribute to the development of—IBS, careful examination of the body of literature is necessary to determine whether there is sound basis for this theory, as gene discovery still requires considerable time, effort and, thus, financial resources. Alternative hypotheses, such as environmental exposures, certainly exist and cannot be ignored as important players in IBS. This article provides a summary of the studies around the competing hypotheses of “gene versus environment” or “nature versus nurture” in IBS. An overview of family studies, candidate gene studies, and alternative hypotheses for IBS are covered, to provide the reader an overview of the works conducted in this area.

IBS as a complex genetic disorder

Classic Mendelian genetics diseases are typically caused by a few highly penetrant genetic defects on a single gene and are transmitted in a typical pattern through families. Mendelian diseases follow an autosomal dominant, recessive, codominant, or X-linked pattern of transmission through pedigrees. Recent genetic studies have focused less on Mendelian disorders and more on complex genetic diseases. A “complex genetic disease” is defined as a multifactorial genetic disorder resulting from multiple genetic variants on several genes (ie, polygenic) with contributions from environment and lifestyle. These genetic effects are modest in that the presence of a specific variant is rarely sufficient on its own to result in disease development. Complex genetic diseases are still heritable in that they tend to aggregate in families, but not in the same predictable fashion as classic Mendelian disorders.

Many common diseases of significant public health interest are thought to be complex disorders. Heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, autism, and mood disorders are a few of the diseases and disorders under study by geneticists and genetic epidemiologists. In gastroenterology, Crohn’s disease is the best example of a complex genetic disorder with successful susceptibility loci identification. A combination of family-based linkage studies, candidate gene and fine-mapping studies, as well as genome-wide association studies have led to the identification of several genes—such as NOD2 , ATG16L1 , IL23 , IL12B , STAT3 , NKX2-3 —found to be consistently associated with Crohn’s disease. These discoveries offer the promise that if gene discovery was possible in this complex gastrointestinal disorder, successful gene discovery is feasible in other multifactorial disorders and diseases including IBS.

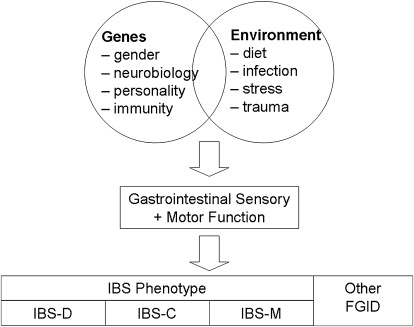

Despite the discovery of several genetic loci involved in the development of Crohn’s disease, it is clear that genes alone do not cause the disease and that environmental contributions, such as diet, smoking, early exposure to infectious organisms, and colonic microflora, are still important. A similar gene-environment paradigm could be proposed for IBS ( Fig. 1 ) whereby a combination of genetic factors and environmental factors result in the alterations in gastrointestinal sensation and motor function that ultimately result in manifestation of symptoms. Genetic variation in genes that encode proteins that regulate gender-based biologic processes, control or modulate central or peripheral sensation and motility, or even regulate brain response to stress would be the obvious first candidates for IBS. These factors, interacting with environmental factors such as diet, infection, and early life trauma and stress, are likely responsible for the overall IBS phenotype. However, the specific combinations of genetic variants and environmental factors likely can in part explain the clinical heterogeneity of IBS. Hence, it is conceivable and likely that genes responsible for diarrhea are different to those responsible for constipation, and other genetic variants that predispose an individual to developing or sensing abdominal pain required for IBS are not generally present in the nonpainful functional disorders such as functional constipation and functional diarrhea. Exploring gene-environment interactions will be important if one postulates that IBS is a multifactorial, polygenic complex genetic disorder.

IBS and heritability

Genetic diseases—complex or Mendelian—must run in families. Several studies of patients with IBS suggest that this disorder aggregates in families, and thus appears potentially heritable. Children with persistent recurrent abdominal pain who were found to report IBS-like symptoms as adults were almost threefold as likely to have at least one sibling with similar symptoms when compared with children-now-adults without IBS-like symptoms (40% vs 6%, P <.05). Another study of IBS outpatients showed that one-third reported another family member with IBS, even in patients without a concurrent psychiatric diagnosis. In another study, having a first-degree relative with IBS was one of the characteristics found to be predictive of IBS over other gastrointestinal disorders among outpatients consulting their general practitioner for chronic abdominal pain.

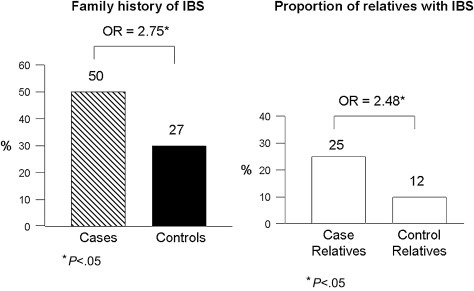

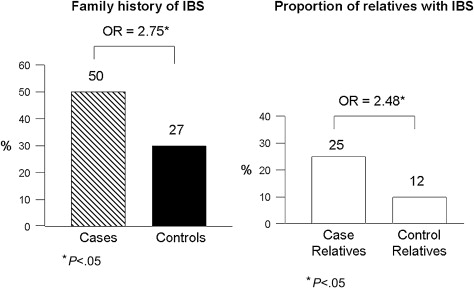

The majority of original studies evaluating familial clustering of IBS has been based predominantly on patient reports of having another affected family member with IBS: proxy reporting. However, one study by the author’s group has shown that accuracy of patient reporting on a specific relative’s IBS status is poor. As a consequence, a large family case-control study was performed, which collected bowel symptom and medical history data directly from cases, controls, and their first-degree relatives. This study of 477 cases, 1492 case-relatives, 297 controls, and 936 control-relatives found that 50% of case-families and 27% of control-families had at least one other relative with IBS ( P <.05) ( Fig. 2 ). The magnitude of this effect was an odds ratio of 2.75 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.01–3.76). When looking at the absolute proportion of relatives affected, 25% of case-relatives reported having IBS compared with 12% of control-relatives ( P <.05). Furthermore, the magnitude of familial aggregation did not vary by gender of the proband, with males and females being equally likely to have an affected relative or set of relatives. Although confidence intervals overlapped, there was a trend for the strength of aggregation to be greatest among probands with diarrhea, followed by constipation, and then mixed bowel habits. Prior intestinal infections, abuse, and depression or anxiety were more common among cases than controls, and among affected relatives than unaffected relatives. The overall prevalence of these risk factors was 9% of affected relatives reporting a prior infection (vs 5% among controls), 35% reporting abuse (vs 25%), and 44% reporting depression or anxiety (vs 22%). Thus, a family member of an individual with IBS is 2 to 3 times more likely to have IBS; familial clustering is present irrespective of predominant bowel pattern; and the known environmental risk factors for IBS are also common in IBS families.

Study of the pattern of IBS transmission through families has yielded additional interesting observations. A recent study of children with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs; but not IBS exclusively), their parents, and their child-aged siblings showed that all mothers, fathers, and siblings of cases were more likely to be affected with another FGID than matching control-relatives. Mothers were the most likely to have an FGID (49.6% case-mothers vs 21.4% control-mothers, P <.05), followed by their child-aged siblings (26.4% vs 17.6%, not significant), then fathers (13.6% vs 9.3%, not significant). By contrast, a study of adult patients with IBS by the author’s group showed that adult-aged case-siblings had the highest risk of concurrent IBS, followed by their adult-aged children, and then parents. Although female relatives were more likely to be affected with IBS, both genders were still at risk for IBS compared with control-relatives. When formal segregation analysis was performed to determine whether the pattern of transmission of IBS through pedigrees is consistent with Mendelian models (eg, autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, and so forth), IBS transmission was not consistent with the sporadic model, meaning IBS appeared consistently in families and in parents, arguing against random mutations causing IBS. More importantly, there was general lack of convergence of the data with segregation analysis. This finding suggests that IBS does not result from a single, major locus, that there was incomplete penetrance, or that IBS could be the result of genetic and environmental factors. Overall findings indicate an underlying genetic basis for IBS.

Although IBS appears to run in families, the previously cited studies suggest that there may be individuals with “sporadic” or nonfamilial IBS as well as individuals with a familial form of IBS. This observation begs the question as to whether there are clinical characteristics suggesting a distinct mechanistic basis for the sporadic and familial forms of IBS. Genetic diseases may present at an earlier age or present with a more specific form of disease, as observed with hereditary colon cancer syndromes. The author’s group found that cases with a stronger family history of IBS had more severe pain, had concurrent fibromyalgia, heartburn, and asthma, and reported symptoms of loose stools, urgency constipation, and pain compared with those with less of a family history of IBS ( P <.05). Age of onset was not predicted by family history of IBS, thus demonstrating that patients with a family history did not experience onset of IBS symptoms at a younger age than patients without a family history of IBS. Although at a univariate level of analysis, somatization level and personal or family history of psychiatric history or abuse were more common among individuals (probands and relatives) with IBS, these factors were not predictive of familial IBS with univariate or with multivariate analyses, suggesting that familial clustering was not related to psychological or psychiatric disease. Kanazawa and colleagues has shown that among IBS patients reporting a parental history of bowel problems, these individuals exhibit higher levels of psychological distress. These studies suggest that familial forms of IBS are characterized by greater pain severity and greater comorbidity, including perhaps psychological distress.

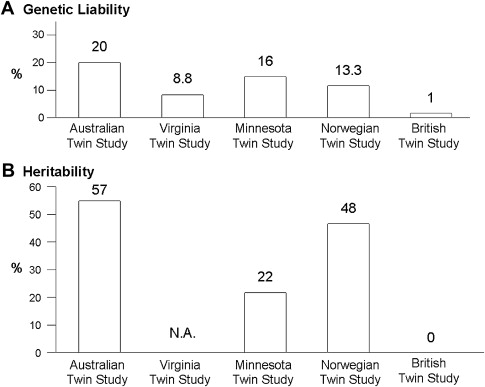

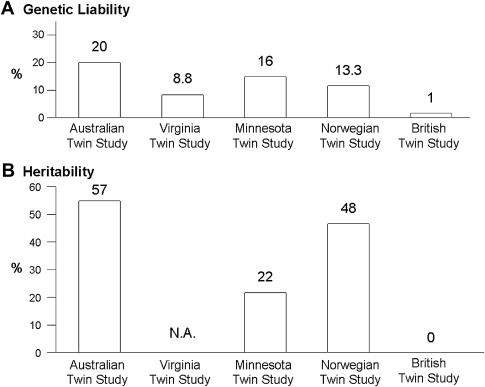

Twin studies also support the concept that IBS may be a complex disorder with genetic as well as environmental contributors. To date, there have been at least 5 twin studies of IBS or functional bowel disorders, estimating that the genetic liability ranges between 1% and 20% with heritability estimates ranging between 0% and 57% (see Fig. 2 ). In all but one study, the concordance rates for monozygotic twins (who are genetically identical) were higher than the concordance rates for dizygotic twins, suggesting an underlying genetic etiology. Nonetheless, Mohammed and colleagues found that concordance rates for monozygotic and dizygotic twins were similar for IBS using a validated questionnaire and the Rome II diagnostic criteria to make the diagnosis of IBS, thus arguing that genes are not a major factor in IBS development, and certainly not a major gene with a strong effect. Studies with twins reared apart, which would permit greater discernment of the influence of different environments in genetically identical twins, are unfortunately lacking.

Heritability ( h 2 ) is another statistical estimate to quantitate the relative genetic contribution to a trait, relative to its environmental contributors. Heritability is the amount or proportion of phenotypic variance of the disease of interest in the population that is inherited through genetic factors. The twin studies show that the heritability estimates range from 0% in the British Twin Study, 22% in the Minnesota Twin Study, 48% in the Norwegian Twin Study, to 57% in the Australian Twin study ( Fig. 3 ). Using data collected from families and not twin pairs, when the IBS Rome criteria were converted into a quantitative trait based on number of Rome symptoms endorsed and severity, the heritability estimates for IBS ranged from 0.19 to 0.35 depending on the weighting factors for each score. In summary, these studies suggest that the genetic contribution to IBS development is reasonably high and comparable to other diseases for which a genetic basis has been found.

IBS and heritability

Genetic diseases—complex or Mendelian—must run in families. Several studies of patients with IBS suggest that this disorder aggregates in families, and thus appears potentially heritable. Children with persistent recurrent abdominal pain who were found to report IBS-like symptoms as adults were almost threefold as likely to have at least one sibling with similar symptoms when compared with children-now-adults without IBS-like symptoms (40% vs 6%, P <.05). Another study of IBS outpatients showed that one-third reported another family member with IBS, even in patients without a concurrent psychiatric diagnosis. In another study, having a first-degree relative with IBS was one of the characteristics found to be predictive of IBS over other gastrointestinal disorders among outpatients consulting their general practitioner for chronic abdominal pain.

The majority of original studies evaluating familial clustering of IBS has been based predominantly on patient reports of having another affected family member with IBS: proxy reporting. However, one study by the author’s group has shown that accuracy of patient reporting on a specific relative’s IBS status is poor. As a consequence, a large family case-control study was performed, which collected bowel symptom and medical history data directly from cases, controls, and their first-degree relatives. This study of 477 cases, 1492 case-relatives, 297 controls, and 936 control-relatives found that 50% of case-families and 27% of control-families had at least one other relative with IBS ( P <.05) ( Fig. 2 ). The magnitude of this effect was an odds ratio of 2.75 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.01–3.76). When looking at the absolute proportion of relatives affected, 25% of case-relatives reported having IBS compared with 12% of control-relatives ( P <.05). Furthermore, the magnitude of familial aggregation did not vary by gender of the proband, with males and females being equally likely to have an affected relative or set of relatives. Although confidence intervals overlapped, there was a trend for the strength of aggregation to be greatest among probands with diarrhea, followed by constipation, and then mixed bowel habits. Prior intestinal infections, abuse, and depression or anxiety were more common among cases than controls, and among affected relatives than unaffected relatives. The overall prevalence of these risk factors was 9% of affected relatives reporting a prior infection (vs 5% among controls), 35% reporting abuse (vs 25%), and 44% reporting depression or anxiety (vs 22%). Thus, a family member of an individual with IBS is 2 to 3 times more likely to have IBS; familial clustering is present irrespective of predominant bowel pattern; and the known environmental risk factors for IBS are also common in IBS families.

Study of the pattern of IBS transmission through families has yielded additional interesting observations. A recent study of children with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs; but not IBS exclusively), their parents, and their child-aged siblings showed that all mothers, fathers, and siblings of cases were more likely to be affected with another FGID than matching control-relatives. Mothers were the most likely to have an FGID (49.6% case-mothers vs 21.4% control-mothers, P <.05), followed by their child-aged siblings (26.4% vs 17.6%, not significant), then fathers (13.6% vs 9.3%, not significant). By contrast, a study of adult patients with IBS by the author’s group showed that adult-aged case-siblings had the highest risk of concurrent IBS, followed by their adult-aged children, and then parents. Although female relatives were more likely to be affected with IBS, both genders were still at risk for IBS compared with control-relatives. When formal segregation analysis was performed to determine whether the pattern of transmission of IBS through pedigrees is consistent with Mendelian models (eg, autosomal dominant, recessive, X-linked, and so forth), IBS transmission was not consistent with the sporadic model, meaning IBS appeared consistently in families and in parents, arguing against random mutations causing IBS. More importantly, there was general lack of convergence of the data with segregation analysis. This finding suggests that IBS does not result from a single, major locus, that there was incomplete penetrance, or that IBS could be the result of genetic and environmental factors. Overall findings indicate an underlying genetic basis for IBS.

Although IBS appears to run in families, the previously cited studies suggest that there may be individuals with “sporadic” or nonfamilial IBS as well as individuals with a familial form of IBS. This observation begs the question as to whether there are clinical characteristics suggesting a distinct mechanistic basis for the sporadic and familial forms of IBS. Genetic diseases may present at an earlier age or present with a more specific form of disease, as observed with hereditary colon cancer syndromes. The author’s group found that cases with a stronger family history of IBS had more severe pain, had concurrent fibromyalgia, heartburn, and asthma, and reported symptoms of loose stools, urgency constipation, and pain compared with those with less of a family history of IBS ( P <.05). Age of onset was not predicted by family history of IBS, thus demonstrating that patients with a family history did not experience onset of IBS symptoms at a younger age than patients without a family history of IBS. Although at a univariate level of analysis, somatization level and personal or family history of psychiatric history or abuse were more common among individuals (probands and relatives) with IBS, these factors were not predictive of familial IBS with univariate or with multivariate analyses, suggesting that familial clustering was not related to psychological or psychiatric disease. Kanazawa and colleagues has shown that among IBS patients reporting a parental history of bowel problems, these individuals exhibit higher levels of psychological distress. These studies suggest that familial forms of IBS are characterized by greater pain severity and greater comorbidity, including perhaps psychological distress.

Twin studies also support the concept that IBS may be a complex disorder with genetic as well as environmental contributors. To date, there have been at least 5 twin studies of IBS or functional bowel disorders, estimating that the genetic liability ranges between 1% and 20% with heritability estimates ranging between 0% and 57% (see Fig. 2 ). In all but one study, the concordance rates for monozygotic twins (who are genetically identical) were higher than the concordance rates for dizygotic twins, suggesting an underlying genetic etiology. Nonetheless, Mohammed and colleagues found that concordance rates for monozygotic and dizygotic twins were similar for IBS using a validated questionnaire and the Rome II diagnostic criteria to make the diagnosis of IBS, thus arguing that genes are not a major factor in IBS development, and certainly not a major gene with a strong effect. Studies with twins reared apart, which would permit greater discernment of the influence of different environments in genetically identical twins, are unfortunately lacking.

Heritability ( h 2 ) is another statistical estimate to quantitate the relative genetic contribution to a trait, relative to its environmental contributors. Heritability is the amount or proportion of phenotypic variance of the disease of interest in the population that is inherited through genetic factors. The twin studies show that the heritability estimates range from 0% in the British Twin Study, 22% in the Minnesota Twin Study, 48% in the Norwegian Twin Study, to 57% in the Australian Twin study ( Fig. 3 ). Using data collected from families and not twin pairs, when the IBS Rome criteria were converted into a quantitative trait based on number of Rome symptoms endorsed and severity, the heritability estimates for IBS ranged from 0.19 to 0.35 depending on the weighting factors for each score. In summary, these studies suggest that the genetic contribution to IBS development is reasonably high and comparable to other diseases for which a genetic basis has been found.

Environmental factors and familial IBS

Despite the consistent observation that IBS clusters in families, this could still be explained by shared environmental contributors or, less likely, individual environmental exposures. Individual environmental contributors that are not likely to be shared among family members or across generations are not discussed in detail in this review. These exposures include early and later life experiences such as nasogastric tube placement at birth, other painful stimuli experienced during infancy, maternal separation, socioeconomic status, military deployment, and microflora. These individual environmental factors are still potentially important to be included when gene-environment interactions may be required for disease development. This section discusses shared household exposures that could represent an alternative mechanism besides an underlying genetic basis for the familial aggregation observed in the families of patients with IBS. Environmental exposures that could have been shared between multiple family members include verbal abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, shared household stressors (eg, ill family member, unemployment, catastrophe), parenting style, and learned illness behavior.

Verbal, physical, and sexual abuse during childhood has been reported to be more common in patients with IBS than in matched controls in several studies. Up to 50% of patients with IBS may report a history of lifetime victimization. The mechanism by which abuse is associated with, or possibly leads to development of IBS may be the result of psychological factors rather than a fundamental change in gastrointestinal motor and sensory function. Heitkempker and colleagues have shown that among women with IBS, few differences were observed in characteristics in a comparison between those with and without an abuse history. Furthermore, when 4 groups of patients with and without IBS and with and without sexual abuse histories had rectal distension studies performed, although IBS again reported greater sensitivity to rectal distension, sexual abuse did not attenuate results. Ringel and colleagues have also recently shown that the presence or absence of abuse does not alter rectal sensation or lead to increased rectal pain sensation. By contrast, a population-based study found that although childhood abuse was associated with IBS, the abuse was no longer associated with IBS when neuroticism was accounted for and included in the analyses. In the only family study examining the role of abuse, the author’s group has shown that in family relatives, the association between abuse and IBS disappeared after inclusion of somatization in the multivariate model. This finding suggests that either somatization leads to overreporting of abuse or, perhaps more likely, abuse leads to somatization that ultimately results in IBS symptom development and reporting. Furthermore, as the majority of patients with IBS report no history of abuse, abuse is clearly not required for the development of IBS. The familial clustering of IBS is unlikely to be explained by shared household exposure to an abuser, as the prevalence of abuse is the same among familial and nonfamilial, sporadic IBS.

Besides household exposure to abuse, other shared stressors experienced in a family environment, particularly during childhood, could include adverse life events such as loss of a parent or close relative, significant illness in a household relative, singular or recurrent unemployment, and natural disasters. However, adverse childhood events appear very common—approximately 60% of 17,000 adults from a health maintenance organization reported one or more events during childhood, and no secular trends were observed across 4 birth cohorts. Another study specifically comparing the role of early adverse life events among IBS patients and controls with respect to salivary cortisol measurements before and after a visceral stressor found that early adverse life events were present in nearly 50% of patients with IBS as well as their matched controls, and that IBS was equally common among individuals reporting adverse life events as compared with individuals reporting no early life events. Although cortisol levels were higher among individuals reporting adverse childhood events than in those without early events, IBS patients did not have different salivary cortisol responses to stress than controls, and there was only a trend for an interaction between IBS patients who had reported life events and higher cortisol levels compared with controls ( P = .056). Furthermore, although adverse life events appear to be common across time and thus possibly across generations, they are unlikely to be shared across multiple generations, making the hypothesis that they could contribute to familial clustering of IBS less viable.

Besides childhood or early adulthood exposures and stressors, others have suggested that the familial clustering of IBS may be a result of learned illness behavior modeled from parents. Whitehead and colleagues surveyed a sample of the general population in metropolitan Cincinnati and found that individuals with IBS symptoms exhibited somatic behavior (eg, reporting more complaints, consulting physicians for minor complaints) but, importantly, reported being given gifts or special foods as children during illness—findings not found in those in acute diseases such as patients with peptic ulcer and the asymptomatic general population. Another study also confirmed that patients with IBS were more likely to miss school and have more doctor visits as children than individuals without IBS, suggesting that their parents paid greater attention to their illnesses, reinforcing chronic illness behaviors. Levy and colleagues conducted an interview study of mothers with IBS and their children, and compared them to mothers without IBS and their children. The study found that children of mothers with IBS have more gastrointestinal as well as nongastrointestinal symptoms, and have more school absences and physician visits. The investigators found that mother-IBS status was independent of maternal solicitousness (reinforcement of illness behavior) where parent-IBS status influenced children’s perceptions of symptom severity but not their perception of the seriousness of gastrointestinal symptoms, whereas parental solicitousness appeared to influence the children’s reporting of seriousness of symptoms but not severity. Ultimately, the study supported the role of learned illness behavior, although the investigators could not distinguish genetic and environmental contributors to gastrointestinal symptoms.

In summary, shared household environmental factors—whether abuse, other early adverse life events, or learned illness behavior from parental modeling—could explain a subset of cases with IBS, but the degree to which they contribute to familial clustering of IBS still remains to be fully elucidated.

Genetic diseases that mimic IBS

One of the great challenges of studying the genetics of IBS is that there are several disorders with symptoms similar to IBS, and a group of these may also have an underlying genetic basis. These diseases include inflammatory bowel disease (eg, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis) and celiac sprue. These genetic traits may also coexist with IBS—lactose or fructose intolerance, for example—whose presence does not necessarily preclude an IBS diagnosis. As these disorders are not always ruled out before inclusion in family studies, there will always be some degree of uncertainty regarding the potential role of these disorders in the familial aggregation of IBS. Despite this concern of another genetic disorder mimicking IBS, the author’s group found in more than 500 IBS cases that their IBS diagnoses endured over inflammatory conditions after extensive chart review as well as serologic testing for celiac sprue. Celiac sprue was found in only 1% of IBS cases and in a comparable proportion of controls. When Villani and colleagues screened loci associated with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in their sample, IBD loci were not observed in the IBS group. Similarly, the prevalence of lactase nonpersistence was no different between IBS cases and controls (15% vs 14%), suggesting that this autosomal recessive trait is unlikely to explain IBS, let alone explain the familial aggregation of IBS. Nonetheless, as a mimicker, testing for and adjustment for lactose intolerance, inflammatory bowel disease, and celiac disease may be necessary in gene studies of IBS.

In addition to gastrointestinal diseases, it may be important to account for the genetics of other nongastrointestinal disorders such as psychiatric diseases and traits in family studies of IBS, as psychiatric disorders are common in patients with IBS and select antidepressants can be used to treat IBS. Several studies have shown that there is a link between IBS and psychiatric illness, including in families. Sullivan and colleagues reported that among outpatients receiving their first diagnosis of IBS, the prevalence of depression among blood relatives was higher than in controls (5.7% vs 1.8%, P <.05), at a level comparable with a group of individuals with major depression (5%). Although the proportion of relatives with depression was higher in IBS patients, the numbers were still quite low, but the investigators argue that self-report of family history is less reliable and likely represents an underestimate of the true prevalence of depression. Woodman and colleagues conducted interviews of relatives of patients with IBS and patients who had undergone a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and found that the relatives of IBS patients were more likely to report depressive disorders (33.3% vs 17.3%, P = .05) and anxiety disorders (41.7 vs 18.7, P <.05), but not somatoform (2.1% vs 1.8%, P >.05) or substance use disorders (18.8% vs 32.0%, P >.05). Whitehead and colleagues performed a similar study interviewing probands with and without major depressive disorder (MDD) and found that IBS was more common in relatives of probands with MDD than in relatives of probands without MDD (16% vs 7%). In short, there has been a suggestion that IBS is part of a larger genetic psychiatric disorder. However, some could argue that because psychiatric comorbidity is related to health care seeking but is not a common feature in community IBS, it is unlikely that a broader psychiatric trait is the heritable component in IBS. The large family case-control study by the author’s group did not find that a personal history of psychiatry disease, a family history of psychiatric disease, or a family history of alcohol abuse was predictive of familial IBS. Moreover, as discussed in the next section, it was not observed that common genetic variants associated with mood disorders were associated with IBS in the absence of psychiatric disease. Thus, although it is possible that there is a genetic variant responsible for a psychiatric trait linked to IBS, there is likely a separate genetic and biologic mechanism to explain the remaining symptoms of IBS.

Candidate gene and pathway studies

To date, nearly 60 genes have been evaluated to determine whether specific genetic variants may be associated with IBS. The genes, the genetic markers, the findings, and references for these studies are summarized in Table 1 . The genes studied lie in the following main pathways: serotonin, adrenergic, inflammation, intestinal barrier, and psychiatric. The genes studied were selected because of their proteins’ putative role in gastrointestinal motor or sensory function or because of their potential role in resistance or response to microbial organisms. As gastrointestinal motility and sensation are abnormal in a subset of IBS patients, infection is a risk factor for IBS development, and antibiotic therapy can attenuate IBS symptoms, the genes encoding proteins and peptides related to gastrointestinal function pose an attractive target of study. Because the number of genetic markers and genes is too great to review in entirety, this section focuses primarily on genetic pathways and positive findings reported by investigators.