Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is an effective platform for a variety of therapies in the management of benign and malignant disease of the pancreas. Over the last 50 years, endotherapy has evolved into the first-line therapy in the majority of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases of the pancreas. As this field advances, it is important that gastroenterologists maintain an adequate knowledge of procedure indication, maintain sufficient procedure volume to handle complex pancreatic endotherapy, and understand alternate approaches to pancreatic diseases including medical management, therapy guided by endoscopic ultrasonography, and surgical options.

Key points

- •

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is an effective platform for a variety of therapies in the management of benign and malignant disease of the pancreas.

- •

Over the last 50 years, endotherapy has evolved into the first-line therapy in the majority of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases of the pancreas.

- •

Gastroenterologists must maintain knowledge of procedure indication and sufficient procedure volume to handle complex pancreatic endotherapy.

Background

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was first described in 1968 as a diagnostic tool for evaluating disorders of the pancreas or biliary tract. Since then, advances in technique and instruments such as endoscopic sphincterotomy, lithotripsy, and stenting have evolved ERCP from a diagnostic test to a therapeutic platform for a variety of interventions. The usefulness of ERCP in management of malignant obstruction is well-established. In this article, we discuss the usefulness of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) in the management of benign diseases, including acute pancreatitis (AP), recurrent AP (RAP), and chronic pancreatitis (CP), as well as pancreatic duct (PD) leaks, fistulas, and fluid collections. In addition, we will address techniques and interventions used for reducing the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).

Background

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was first described in 1968 as a diagnostic tool for evaluating disorders of the pancreas or biliary tract. Since then, advances in technique and instruments such as endoscopic sphincterotomy, lithotripsy, and stenting have evolved ERCP from a diagnostic test to a therapeutic platform for a variety of interventions. The usefulness of ERCP in management of malignant obstruction is well-established. In this article, we discuss the usefulness of endoscopic retrograde pancreatography (ERP) in the management of benign diseases, including acute pancreatitis (AP), recurrent AP (RAP), and chronic pancreatitis (CP), as well as pancreatic duct (PD) leaks, fistulas, and fluid collections. In addition, we will address techniques and interventions used for reducing the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP).

Acute pancreatitis

AP is common, with more than 200,000 admissions annually in the United States. The 2 most common etiologies of AP are heavy alcohol consumption and gallstones, which account for up to 80% of AP. In up to 20% of cases, no etiology can be identified readily after a thorough history, physical examination, and abdominal imaging. In prospective studies of a single episode of idiopathic AP, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) has been shown to reliably identify the cause in up to 79% of cases, with common findings including choledocholithiasis, biliary sludge, CP, or tumor not seen on cross-sectional imaging. As such, EUS is recommended in individuals 40 years of age or older with AP and no identifiable etiology.

Given the accuracy of EUS and favorable safety profile, ERCP after a single episode of unexplained pancreatitis is generally not recommended. However, there are certain situations, such as gallstone pancreatitis, wherein early ERCP can facilitate an endoscopic intervention in AP that has favorable outcomes.

Gallstone Pancreatitis

Gallstone pancreatitis accounts for between 35% and 60% of all cases of AP. Most cases are typically self-limiting, but up to 25% of cases can be severe with associated end-organ dysfunction and death, with a mortality rate between 5% and 10%. An increase in the alanine aminotransferase of greater than 3 times the upper limit of normal has a positive predictive value of gallstone pancreatitis of 95%. The exact mechanism by which passage of gallstones results in pancreatitis is unknown. One theory proposes that the pathophysiology of gallstone pancreatitis occurs in 2 phases. The first phase is the passage of a small gallstone through the distal duct, initiating the attack of AP. A patent ampulla allows for flow of pancreatic digestive enzymes and a mild attack. In the second phase, additional stones pass through the duct or a stone becomes lodged in the distal duct resulting in either a transient or a continuous obstruction in the common bile duct and PD. The obstruction prevents outflow of activated pancreatic enzymes, PD hypertension, and increased pancreatic enzyme activation. Prior studies have shown an increased incidence of retained stones in severe forms of gallstone pancreatitis compared with mild cases, which forms the theoretic basis for ERCP in AP.

Data on the optimal management of suspected choledocholithiasis in patients with acute biliary pancreatitis are conflicting. Numerous trials have investigated the role of early ERCP (within 72 hours of admission) with or without sphincterotomy compared with conservative management with disparate results. Some studies indicated a benefit for early ERCP, whereas others had worse outcomes compared with conservative management. Given the heterogeneity of these studies, multiple metaanalyses and systematic reviews on this topic have been conducted with different inclusion criteria and, therefore, have arrived at different conclusions. Many of the original studies included a high percentage of patients who underwent ERCP without identification of any common bile duct stone. In addition, one of the key confounders in this literature is the presence of cholangitis, which has clear data to support the use of early ERCP for decompression.

The most recent metaanalysis on this subject, which specifically excluded cholangitis, showed no significant benefit for early ERCP with or without sphincterotomy on morbidity (relative risk [RR], 0.82; 95% CI, 0.64–1.04) or mortality (RR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.61–2.45), regardless of the predicted severity of gallstone pancreatitis. Another review with slightly different inclusion criteria had a similar finding that early ERCP in the absence of cholangitis was associated with a nonsignificant reduction in overall complications (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.41–1.04) but a nonsignificant increase in mortality (RR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.23–5.63). If a patient has evidence of cholangitis with AP, early ERCP reduces mortality significantly (RR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.06–0.68) as well as local and systemic complications (RR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.20–0.99). Similarly, if a patient has evidence of biliary obstruction (conjugated bilirubin of >2 mg/dL and common bile duct dilation of >6 mm, gallbladder in situ) and AP, early ERCP significantly reduced local and systemic complications (RR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.32–0.91). Given these findings, ERCP should only be performed in the setting of AP with coexisting cholangitis or persistent biliary obstruction.

Post–Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is the most common serious adverse event associated with ERCP with an incidence of 3% to 10% in most large series. Certain patient and procedure-related recognized risk factors are associated with a higher incidence of PEP ( Box 1 ).

Patient-related Risk Factors

Prior PEP

Suspected SOD

Previous recurrent acute pancreatitis

Female gender

Younger age

Normal serum bilirubin

Absence of pancreatic mass or chronic pancreatitis

Procedure-related Risk Factors

Difficult cannulation

Pancreatic sphincterotomy

Contrast injection into the pancreatic duct

Biliary sphincter balloon dilation of an intact sphincter

Abbreviations: PEP, post endoscopic retrograde pancreatography pancreatitis; SOD, Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction.

The administration of rectal indomethacin and certain procedural techniques such as wire-guided access and pancreatic stent placement, can mitigate the risk of PEP. Trauma-induced papillary edema can lead to pancreatic sphincter obstruction and resultant ductal hypertension. It is thought that, by immediately placing a PD stent, the pressure gradient is decreased across the pancreatic sphincter and the risk for PEP is also decreased. In patients who are perceived to be at high risk for PEP, prophylactic pancreatic stent placement decreases the risk of pancreatitis (15.5% vs 5.8%). This reduction translates to a number needed to stent of only 10 to prevent 1 episode of PEP. In a recent metaanalysis (n = 1422), the administration of rectal indomethacin near the time of ERCP reduced the risk of PEP (odds ratio [OR], 0.49; 95% CI, 0.34–0.71; P <.01) as compared with placebo. The timing of administration has varied in multiple studies including 2 hours before, immediately before, during, and immediately after ERCP with similar results. There is ongoing research to evaluate whether the administration of indomethacin alone is sufficient to protect against PEP; however, currently, the administration of indomethacin (100 mg per rectum administered periprocedurally) in addition to placement of a PD stent is suggested for prevention of PEP in high-risk patients. At this time, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology guidelines state that rectal nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, if available, should be considered in preventing PEP in high-risk individuals.

Recurrent acute pancreatitis

RAP is defined as the occurrence of 2 or more episodes of AP in a patient without any evidence of CP. In a patient with an initial episode of AP, the lifetime risk of RAP is 17% to 20%. Much like AP, the most common etiologies of RAP include heavy alcohol use and gallstones. The etiology of RAP can be identified in the majority of patients. Other common etiologies include anatomic variants such as pancreas divisum or aberrant pancreatobiliary junction, sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD), hereditary etiologies (CFTR, PRSS1, SPINK1), and metabolic conditions such as hypercalcemia and hypertriglyceridemia. A thorough history and physical examination in conjunction with a complete metabolic panel, transabdominal ultrasonography, MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), and computed tomography (CT) scan detect the cause of RAP in 70% of cases.

Pancreas Divisum

Pancreas divisum is a congenital variant in the anatomy of the PD system. The ventral and dorsal PDs fail to fuse during organogenesis and the majority of the pancreas is drained via the dorsal duct into the minor papilla. This variant is relatively common and present in 2% to 10% of the population in autopsy studies. Although most patients with this ductal variant are asymptomatic throughout life, there is a small subset (approximately 5% of patients with divisum) that develops AP and/or chronic abdominal pain. Although pancreas divisum is often present in individuals with idiopathic AP, the role of divisum as a cause of RAP or CP is controversial. The presence of divisum does not automatically implicate that as the cause of AP or CP. The putative hypothesis is that the caliber of the minor papilla is too narrow to drain the pancreatic secretions via the dorsal duct creating a relative outflow obstruction as seen on secretin stimulated MRI studies leading to pain and possibly acute or CP or increased risk of pancreatitis from accepted stimuli such as alcohol or CFTR mutations.

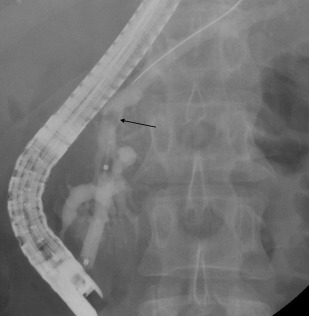

The gold standard for diagnosis of divisum is ERP. Contrast injection into the ventral duct through the major papilla shows a short duct tapering terminally into side branches within the pancreatic head, whereas injection through the minor papilla demonstrates a patent dorsal system draining the pancreatic body and tail ( Fig. 1 ). However, this modality is not the favored diagnostic test for divisum owing to a significantly higher rate of post-PEP with dorsal duct cannulation (OR, 7.45; 95% CI, 3.25–17.07). As such, alternative diagnostic tests are preferred to establish the presence of divisum, including EUS, CT, and MRI. In a retrospective review of all patients who had a diagnosis of pancreas divisum confirmed on ERP, the sensitivity of EUS for pancreas divisum was 86.7%, significantly higher than sensitivity for CT (15.5%) or MRCP (60%). An infusion of secretin before MRCP (secretin-enhanced MRCP) significantly increases the sensitivity (84.5 vs 74.2; P = .02) and specificity (88.1 vs 76.2; P = .01) of diagnosing pancreas divisum compared with traditional MRCP.

Much like the causal relationship between pancreas divisum and pancreatitis, the usefulness of endotherapy in preventing recurrent pancreatitis or improving abdominal symptoms in patients with identified pancreas divisum is an area of debate. The goal of endotherapy is to enlarge the orifice of the minor papilla through papillotomy or stenting to relieve the presumed obstruction of pancreatic exocrine flow. One of the original studies was a small clinical trial of patients with pancreas divisum and at least 2 prior documented episodes of pancreatitis. Patients were randomized to either ERP via the minor papilla with dorsal duct stenting versus no intervention. Over a follow-up period of 30 months, the stenting group had significant fewer hospitalizations, documented episodes of pancreatitis, and baseline episodes of abdominal pain. Many larger studies have been conducted since that time with promising results on preventing RAP but limited benefit in the treatment of chronic pain. A retrospective evaluation of 24 patients with divisum and RAP without CP were treated with either minor papilla sphincterotomy or dorsal duct stenting and followed for a median of 39 months (range, 24–105). There was a significant decrease in recurrent episodes of pancreatitis, but no benefit in baseline pain control. Results of endotherapy in patients with evidence of CP and divisum in preventing RAP seem less promising. In a retrospective study of 113 patients who had undergone endotherapy for divisum, primary success defined as either a clinical improvement or cure was noted to be 53.2% in RAP patients, but only 18.2% patients with features of CP. On multivariate analysis, younger age (46.5 vs 58; P <.0001) and CP (OR, 0.10; 95% CI, 0.03–0.39) were independent predictors of failed response to endotherapy. A recent metaanalysis on this subject included 838 patients from 22 studies. Patients with RAP had a response rate ranging from 43% to 100% (median, 76%). Response rates were lower for patients with CP (21%–80%; median, 42%) and chronic abdominal pain (11%–55%; median, 33%). Given these findings, it seems reasonable to suggest endotherapy for patients with divisum who have clearly documented episodes of RAP without another obvious etiology. Because these patients are at increased risk for PEP, administration of rectal indomethacin is recommended to reduce that risk. Routine endotherapy in patients with CP and/or chronic abdominal pain in the presence of pancreas divisum is not recommended, and needs to be individualized on a case-by-case basis.

Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction

SOD is a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes. Biliary SOD typically presents as biliary type pain, and is often seen in patients after cholecystectomy, whereas pancreatic SOD is associated with idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis.

The revised Milwaukee Biliary Group classification has been used to diagnose, categorize, and drive intervention in suspected SOD patients. Type I biliary SOD consists of patients with biliary-type pain, abnormal aminotransferases, bilirubin or alkaline phosphatase (>2 times normal values) documented on 2 or more occasions, and a dilated bile duct (>8 mm on ultrasound). Approximately 65% to 95% of these patients have manometric evidence of biliary SOD. Type II patients present with biliary-type pain and one of the laboratory or imaging abnormalities mentioned. Approximately 50% to 63% of these patients have manometric evidence of biliary SOD. Type III patients present with recurrent biliary-type pain without any other findings. Approximately 12% to 59% of these patients have manometric evidence of biliary SOD.

Management of type I SOD is accepted to be ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy without the need for sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM). Type II SOD has less objective evidence of a fixed abnormality compared with type I. It is recommended that all patients with suspected type II SOD undergo ERCP with SOM-directed sphincterotomy or empiric biliary with or without pancreatic sphincterotomy. The recommendation for SOM in patients with suspected type II SOD is based on 2 prior randomized clinical trials, the largest of which included 47 patients. All patients underwent SOM and then were randomized to either a true biliary sphincterotomy or a sham sphincterotomy. At 1-year follow-up, there was a significant improvement in pain in patients who had undergone sphincterotomy (65% vs 30%; P <.01), which was best predicted by a SOM basal pressure of greater than 40 mm Hg. Patients in the sham sphincterotomy were crossed over to open-label sphincterotomy and again an elevated basal pressure was predictive of a response to endotherapy. Conversely, large retrospective or nonrandomized trials have shown that the result of SOM is less predictive of response to sphincterotomy. Three trials where sphincterotomy was performed in all patients with suspected type II SOD had a good clinical response (47%–100%) without any correlation to SOM. Other studies have shown a good pain response to empiric sphincterotomy without performance of SOM or need for pancreatography. It is because of this unclear relationship between manometric findings, disease etiology, and response to therapy that the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and experts in the field acknowledge that ERCP with empiric biliary sphincterotomy is an alternative to SOM-guided therapy.

The recently conducted EPISOD (Evaluating Predictors and Interventions in Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction) trial may have been the definitive study to show that there is no role for endotherapy in individuals with type III SOD. In this multicenter, sham-controlled, randomized clinical trial, 214 patients with typical biliary type pain after cholecystectomy without laboratory abnormality or biliary dilation were randomized to sphincterotomy or sham regardless of SOM findings. Patients with increased pancreatic sphincter pressures on SOM who were randomized to the sphincterotomy arm were then randomized again to biliary or both a biliary and pancreatic sphincterotomy. There was a significant improvement in pain in the sham group compared with the sphincterotomy group (37% vs 23%; P = .01). In addition to not providing any relief of pain, there was a 12% rate of PEP despite the placement of a PD stent in all patients. Based on these results, patients with type III SOD should not be offered ERCP or sphincterotomy.

Although biliary SOD is associated with a specific pain syndrome and risk for PEP, pancreatic SOD is thought to be a risk factor for RAP. In patients previously diagnosed with idiopathic RAP, manometric evidence of SOD is considered to be a risk factor for a future episode of pancreatitis (hazard ratio, 4.3; 95% CI, 1.3–14.5; P <.02).

Like biliary SOD, pancreatic SOD has 3 subtypes. Type I refers to patients with typical pancreatic type pain with an increased serum amylase or lipase more than 1.5 to 2 times the upper limit of normal on 2 separate occasions and pancreatic ductal dilation (≥6 mm in the head and ≥5 mm in the body). Type II includes patients with pancreatic type pain with either increased pancreatic enzyme levels or ductal dilation. Finally, type III refers to patients with pancreatic type pain in the absence of laboratory or radiographic abnormalities.

In patients who have RAP and manometrically confirmed SOD, sphincterotomy has been effective in reducing the rate of recurrent pancreatitis and improving pancreatic type pain. Although these studies were statistically significant in reducing the rate and frequency of AP, the rate of at least 1 recurrent episode of pancreatitis in patients who had undergone sphincterotomy was still 51% at 11 years of follow-up. Of note, the rate of recurrent pancreatitis was not different in patients who underwent biliary sphincterotomy (51.5%) versus dual biliary and pancreatic sphincterotomy (52.8%). As such, pancreatic sphincterotomy should not be pursued in this patient population given the independent risks associated with this procedure.

Chronic pancreatitis

CP is an irreversible inflammatory process leading to fibrotic changes with destruction of the pancreatic parenchyma with impairment of the exocrine and endocrine function. Based on morphology, CP can be classified as a large duct type and a small duct type, both of which can occur with or without calcifications. ERP can play 2 major roles in CP: diagnostic in the setting of uncertainty and therapeutic ductal drainage in the setting of large duct disease. The goal of main pancreatic duct (MPD) drainage is relief of ductal hypertension and subsequent pain control.

ERP is sensitive for identifying ductal changes in CP, but cannot assess for parenchymal changes and is thus insensitive for evaluating for minimal change disease. The Cambridge classification of pancreatography findings is the traditional system to identify patients with CP and grade severity. The classification is based on changes in the MPD including dilation, strictures, and irregular contour, as well as the number of irregular side branches plus miscellaneous features, such as filling defects in the MPD or filling cavities. As it turns out, these findings have poor sensitivity and specificity. The results are operator dependent with respect to both interpretation of the pancreatogram, and performance of an adequate contrast injection to ensure proper duct filling. In addition, findings that are classified as CP by the Cambridge classification can also be seen in older patients or in patients who drink alcohol without any other clinical or radiographic features of CP. Most important, pancreatography cannot assess properly parenchymal changes that are the primary finding in minimal change CP. In some cases of CP, no obvious changes are noted on imaging and the diagnosis is made on a basis of exocrine insufficiency. It is for this reason that other diagnostic tests are preferred to establish the diagnosis of CP, with ERP typically reserved for therapy.

Pancreatic endotherapy may be effective in relieving pain in individuals with uncomplicated chronic calcific pancreatitis and should be considered as the first line therapy for ductal decompression. It can be achieved by performing pancreatic sphincterotomy, stricture management with dilating and placement of pancreatic stents, and stone lithotripsy. Clinical response should be evaluated at 6 to 8 weeks. If there is no improvement in subjective measurements of pain or objective improvements in weight, diarrhea, or nutrition, then surgical decompression should be pursued. In a randomized clinical trial comparing endoscopic and surgical drainage of the MPD, surgery had significant improvement in pain (75% vs 32%; P = .007) and heath summary scores. Rates of complication, duration of hospital stay, and changes in pancreatic function were similar between the 2 groups. This study only enrolled 39 patients in total and many experts feel that surgical intervention carries increased risks relative to endoscopic therapy. Regardless of the modality, smoking and alcohol cessation should be part of the treatment recommendations.

Pancreatic Duct Strictures

In a large, multicenter study of endoscopic therapy in CP, MPD obstruction was caused by strictures (47%), stones (18%), or a combination of both (32%). MPD strictures may be single or multifocal. Most strictures occur in the pancreatic head caused by inflammation or fibrosis. A dominant stricture is defined as having at least one of the following characteristics: upstream MPD dilation 6 mm or greater in diameter or prevention of contrast outflow along a 6-Fr catheter inserted upstream from the stricture. The presence of multiple or tail strictures is the main predictor of pain recurrence.

CP is associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer. Approximately 2% of patients with a new diagnosis of CP have an underlying pancreatic malignancy. As such, MPD strictures must be evaluated carefully using contrast-enhanced cross-sectional imaging such as a pancreas protocol CT. In addition, consideration should be given to assessment of tumor markers and extensive sample collection, including EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of suspicious areas.

The goal of endotherapy in PD strictures is remediation of the strictures to allow pancreatic drainage. These strictures tend to be very tight and require serial dilation and stent placement. The first part of stricture management is performing a pancreatic sphincterotomy. Unlike biliary stenting, a pancreatic sphincterotomy was performed before MPD stenting in all major trials and is recommended by the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. A short, 5- to 6-mm pancreatic sphincterotomy is performed with the cutting wire oriented to the 1 to 2 o’clock position with the very distal part of the cutting wire. An isolated pancreatic sphincterotomy is not associated with an increased risk for biliary stenosis and thus a concomitant biliary sphincterotomy is not necessary. Once the pancreatic sphincterotomy is performed, attention is paid to stricture management. The standard of care is to perform dilation followed by stent placement. Dilation alone is typically not effective and not recommended. The size of the stent should be chosen to be at least as large as the PD and traverse the stenosis but short enough to minimize ductal changes. A 10-Fr plastic stent has been associated with a decreased hospital admission rate when compared with other smaller stent sizes.

Alternatively, other trials have used multiple, smaller caliber plastic stents to avoid blockage of side branches. There have been no trials comparing the efficacy of a single large plastic stent versus multiple smaller stents. Pancreatic stents are prone to occlusion in this indication and stent exchange should be planned every 3 to 6 months for an expected total duration of 12 to 24 months. There have been limited number of case series using fully covered self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) with management of MPD strictures with good efficacy; however, the data are too sparse to recommend this approach at this time.

Criteria for definitively removing the stent consists of adequate outflow of contrast medium into the duodenum within 1 to 2 minutes after ductal filling upstream from the dilated stricture immediately after stent removal plus extraction of ductal debris, and easy passage of a 6-Fr catheter through the dilated stricture. The size of the MPD after the stenting protocol is not predictive of pain recurrence even in the presence of a persistent stricture.

Regardless of the size and length of stent chosen, endoscopic therapy with dilation and stenting for MPD strictures without intraductal stones has been effective in decreasing abdominal pain in 65% to 84% of patients. After definitive stent removal, 27% to 38% of patients will relapse with pain at a median of 25 months. With a pain relapse, patients should be offered restenting. Long-term follow-up of MPD stenting shows similar efficacy with satisfactory pain control in 52% to 90% of patients when followed out to 6 years with fewer than 30% of patients ultimately needing surgical decompression.

Complications of MPD stenting can occur. Stent occlusion was the most common (65% at 3 months in 1 study), and is the reason for the planned stent exchanges a priori. Stent migration occurred in 10% of the study patients. Stent migration can be distal with impaction on the opposite wall of the duodenum and rarely results in perforation. Alternatively, proximal migration, which can be technically challenging to manage, particularly in the presence of a high-grade stricture, can occur into the pancreas. Careful selection of stents such as those with side wings and pigtail stents can decrease the risk of migration.

Pancreatic Duct Stones

Similar to MPD strictures, PD calculi are a common complication of CP and produce pain by causing upstream dilation and ductal hypertension ( Fig. 2 ). PD stones are seen in approximately 50% of patients with CP. Stones less than 5 mm in size without any evidence of an MPD stricture can typically be removed by a Dormia basket or an extraction balloon after a pancreatic sphincterotomy. Complete or partial pain relief after pancreatic sphincterotomy and mechanical stone extraction is seen in 50% to 77%. However, in cases of stones greater than 5 mm in diameter, which is larger than the MPD size, located upstream of MPD stricture or impacted in the head of the pancreas, standard extraction techniques are typically ineffective. In these cases stone fragmentation with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is helpful and considered first-line therapy.

The aim of ESWL is to fragment calculi in the MPD to less than 3 mm in size. Multiple metaanalyses have demonstrated the efficacy of ESWL for ductal clearance and pain control. An analysis of 17 studies with a total of 491 patients revealed a clearance rate between 37% to 100% and good pain relief. Another review of 11 studies with more than 1100 patients showed successful stone fragmentation in 89% of patients. A large, single-center study of 1006 patients demonstrated complete pain relief in 42% of patients in 24 to 36 months of follow-up. Only 5% of patients had persistent severe pain.

ESWL therapy is typically offered to patients with large calculi in the head or body and pain as their main complaint. Relative contraindications are patients with isolated calculi in the tail, multiple MPD strictures, mass in the head of the pancreas, pseudocysts or walled off pancreatic necrosis, and pregnancy. Epidural anesthesia is preferred if available. Recurrence of stones is seen in 23% of patients after more than 60 months of follow-up. Minor side effects such as pain and bruising of skin at the site of shock delivery have been described, as well as more serious complications such as pancreatitis, sepsis, and gastric submucosal hematoma.

A comparison of multimodality therapy with ESWL in combination with MPD stenting versus ESWL alone in patients with CP and PD stones demonstrated that pain relapse at 2 years was similar in both groups (45% vs 38%; P = .63); however, the cost of the additional endotherapy added almost 3 times the cost. The addition of ESWL to endoscopic stenting and stone clearance has been shown to be effective. One study of 120 patients demonstrated partial pain relief in 85% and complete pain relief requiring no narcotics in 50% after a mean follow-up of 51 months. As such, the current American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guidelines recommend that ESWL be used as an adjunct for patients with symptoms attributed to pancreaticolithiasis who are refractory to standard ERCP stone extraction techniques.

Intraductal lithotripsy using laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy through direct pancreatoscopy is only recommended as second line management if ESWL is not effective or available. Despite that, per oral pancreatoscopy is attractive because it allows for intraductal lithotripsy during the same session as stricture management via ERCP. A large, retrospective study of 46 patients treated over 11 years for PD stones using per oral pancreatoscopy–directed laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy had a clinical success of complete stone clearance in 74% of patients after a median of 2 ERCPs. There was no difference in efficacy between patients treated with laser or electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Similarly, a multicenter study reported a clinical success of 89% in per oral pancreatoscopy–directed laser lithotripsy for PD stones. The recent introduction of a digital cholangiopancreatoscope is likely to increase this approach compared with ESWL going forward.

Autoimmune Pancreatitis

Autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) is a distinct form of pancreatitis associated with minimal pain, obstructive jaundice with or without a mass, and hypergammaglobulinemia that readily responds to steroid therapy. There are 2 forms of AIP. Type 1 is the classic disease phenotype more commonly seen in Asia of older males (>80% are males >50 years of age). It is associated with a lymphoplasmocytic sclerosing pancreatitis on histology and elevated serum levels immunoglobulin (Ig)G4. In addition to the pancreas, there is often multi-organ involvement in IgG4-associated systemic disease including biliary, eye, kidney, retroperitoneum, and salivary glands. Type 2 AIP is seen in younger patients and is more common in the West. It is a duct-centric pancreatitis with a dense neutrophilic infiltration. Unlike type 1 AIP, serum levels of IgG4 are not increased in type 2. In addition, it is a disease isolated to the pancreas without systemic involvement.

ERP may play an important role in the diagnostic pathway in AIP. The International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for AIP recommends a pancreatogram be performed when the diagnosis of AIP (type 1 and type 2) is not conclusive based on imaging and laboratory assessment. In addition, if type 2 AIP is suspected, the expert guideline recommends pancreatogram be performed if a core biopsy is not performed or inconclusive. Typical pancreatogram findings in AIP include a long MPD stricture greater than one-third of the length of the duct, or multiple strictures without upstream dilation. Less specific findings include a focal stricture without upstream ductal dilation and side branches arising from a strictured segment. ERP has a reported sensitivity of 44% and specificity of 92%. Interobserver agreement is poor, with endoscopists in Asia outperforming their Western colleagues. In addition to performing a pancreatogram, ampullary biopsies with staining for IgG4 are recommended at the time of ERCP. The biopsies have a sensitivity of 52% to 80% and specificity of 89% to 100% in the diagnosis of type 1 AIP.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree