The modern management of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding includes, in selected patients, the performance of timely multimodal endoscopic hemostasis followed by profound acid suppression. This article discusses the available data on the use of antisecretory regimens in the management of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers, which are a major cause of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and briefly addresses other medications used in this acute setting. The most important clinically relevant data are presented, favoring fully published articles.

The modern management of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding includes, in selected patients, the performance of timely multimodal endoscopic hemostasis followed by profound acid suppression. This article discusses the available data on the use of antisecretory regimens in the management of patients with bleeding peptic ulcers, which are a major cause of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and briefly addresses other medications used in this acute setting. The most important clinically relevant data are presented, favoring fully published articles.

The biologic rationale for acid suppression in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Acid has been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation and even favors platelet disaggregation. Based on in vitro and animal experiments, the pH target required to avert these deleterious effects and favor hemostasis is thought to approximate 6.0 to 6.5. Acid is also known to facilitate clot lysis through the activation of pepsin, which occurs at pH levels below 2. Acid suppression, leading to pH levels more than 4, may prevent fibrinolysis. The rationale for acid suppression in upper gastrointestinal bleeding is based on the following deleterious effects of gastric acid on clot stability:

Decreased platelet aggregation, and even platelet disaggregation

Increased clot lysis from pepsin activation by acid

Increased fibrinolytic activity that is impaired by acid

A pH of 6.0 to 6.5 is targeted to reverse these effects based on in vitro and animal data.

After endoscopic therapy is performed for a high-risk ulcer lesion (eg, a visible vessel or pigmented protuberance), approximately 72 hours are required for most lesions to evolve and begin to display low-risk ulcer stigmata. This finding is corroborated by most clinical trials, including a recent large international study, that have shown that peptic ulcer rebleeding occurs predominantly during the first 72 hours after endoscopic treatment and the initiation of high-dose intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI) infusion.

Therefore, experts have hypothesized that acid suppression may stabilize intraluminal clots during this high-risk period, and result in a subsequent improvement of outcomes in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. PPIs also exhibit anti-inflammatory properties of unclear clinical relevance discussed later.

Box 1 lists the relevant clinical recommendations for proton pump inhibitor–related use in the acute management of patients with non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Somatostatin and octreotide are not recommended for routine use in patients with acute ulcer bleeding.

H 2 -receptor antagonists are not recommended in the management of patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

An intravenous bolus followed by continuous-infusion PPI is effective in decreasing rebleeding in patients who have undergone successful endoscopic therapy.

The use of intravenous bolus followed by continuous-infusion PPI is cost-effective after endoscopic therapy in the management of patients bleeding peptic ulcers.

In patients awaiting endoscopy, empiric therapy with a high-dose PPI should be considered.

Patients should be discharged with a prescription for a single daily dose of oral PPI for a duration dependent on underlying etiology.

Much inappropriate use of PPIs occurs in the hospital setting.

Tranexamic acid is not recommended in the acute management of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding

Tranexamic acid inhibits plasminogen activators, conferring its effects as an antifibrinolytic drug. Tranexamic acid is known to increase the risk of thrombosis when administered with tretinoin or coagulation factor VIIa. A meta-analysis from more than 20 years ago had found that tranexamic acid decreased mortality rates by 40% relative to placebo, with no effects on rebleeding and surgery rates. The meta-analysis included studies in which endoscopic hemostatic therapy was not performed, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Furthermore, more than 43% of the patients bled from causes other than peptic ulcers. Many more randomized clinical trials would need to be conducted in accordance with current clinical procedures for a conclusion to be drawn on the efficacy of tranexamic acid in treating patients with peptic ulcer bleeding.

Tranexamic acid is not recommended in the acute management of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding

Tranexamic acid inhibits plasminogen activators, conferring its effects as an antifibrinolytic drug. Tranexamic acid is known to increase the risk of thrombosis when administered with tretinoin or coagulation factor VIIa. A meta-analysis from more than 20 years ago had found that tranexamic acid decreased mortality rates by 40% relative to placebo, with no effects on rebleeding and surgery rates. The meta-analysis included studies in which endoscopic hemostatic therapy was not performed, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn. Furthermore, more than 43% of the patients bled from causes other than peptic ulcers. Many more randomized clinical trials would need to be conducted in accordance with current clinical procedures for a conclusion to be drawn on the efficacy of tranexamic acid in treating patients with peptic ulcer bleeding.

Somatostatin and somatostatin analogs are not routinely recommended in the acute management of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding

Somatostatin is initially synthesized as a pre-prohormone that is processed into two active forms: one consisting of 14 amino acids and the other consisting of 28. Somatostatin exerts many inhibitory functions throughout the body. In addition to inhibiting growth hormone and gastrointestinal secretion, it decreases splanchnic blood flow, and therefore has been used in controlling upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Somatostatin exerts its physiologic effects through five different G-protein–coupled receptors, and is unable to be administered orally because it is quickly inactivated by a peptidase enzyme. Octreotide is a cyclic octapeptide somatostatin analog, and is a more potent inhibitor of growth hormone, glucagon, and insulin.

A study comparing the effects of a high-dose pantoprazole continuous infusion to somatostatin concluded that high-dose pantoprazole was superior. This study consisted of 164 patients who received either a continuous infusion of pantoprazole, 8 mg/h, after a 40-mg bolus or a 250-μg bolus of somatostatin followed by infusion of 250 μg/h. Bleeding recurrence was significantly greater in the somatostatin group than in the pantoprazole group. An earlier meta-analysis suggested that the efficacy of somatostatin was based on many trials using now-outdated diagnostic and therapeutic approaches.

In a more contemporary meta-analysis, Bardou and colleagues showed that neither somatostatin nor octreotide improved outcomes compared with other pharmacotherapy or endoscopic therapy. Therefore, somatostatin and octreotide are not recommended for routine use in the management of patients with acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding, but can be considered in patients with massive unresponsive bleeding, even if known to originate from a non-variceal source. These agents are, of course, the preferred approach in the management of patients with variceal bleeding in conjunction with endoscopic ligation.

H 2 -receptor antagonists are not efficacious in the acute management of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding

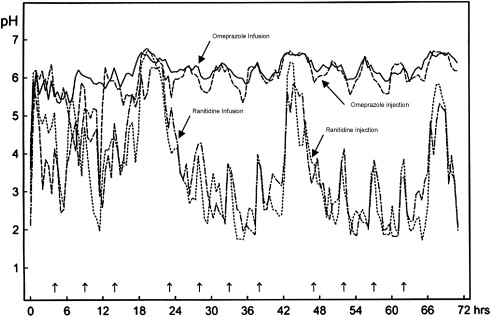

H 2 -receptor antagonists bind competitively and reversibly to H 2 receptors on parietal cells, decreasing parietal secretions in response to histamine. H 2 -receptor antagonists are well absorbed when given orally, but bioavailability varies. A study comparing 72-hour continuous infusion of ranitidine, a H 2 -receptor antagonist, or omeprazole, a PPI, found that the mean number of doses necessary to maintain a pH above 4 increased with ranitidine but decreased with omeprazole, suggesting decreased antisecretory effects as time progressed. This conclusion was also noted by other investigators. This possibility is a serious limitation to the clinical efficacy of H 2 -receptor antagonists because of the rapid development of pharmacologic tolerance to these medications, which can occur as early as 24 hours after the first dose and cannot be overcome by high intravenous doses greater than 500 mg per 24 hours ( Fig. 1 ).

An increasing serum gastrin drive to the parietal cells is one possible mechanism through which tolerance may develop. One large randomized clinical trial and two meta-analyses have now confirmed that no overall benefits are attributable to the acute use of intravenous H 2 -receptor antagonists in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Statistically significant but modest clinical benefits in rebleeding and decreased surgical rates have, however, been noted in a subgroup of patients with bleeding gastric ulcers. The use of H 2 -receptor antagonists in the routine management of patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding is not recommended.

PPIs are efficacious in managing patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding

Mechanism of Action

PPIs are substituted benzimidazole sulphoxides. Under the acidic conditions within the secretory canaliculus of the parietal cells, PPIs are protonated and converted to their active form, which binds covalently to cysteine residues of the H + , K + ATPase enzyme of actively inserted parietal cells, leading to inactivation of the pump. Pumps at rest in the cytosol of the parietal cell are not blocked. Because PPIs bind irreversibly to proton pumps, their biologic activity extends beyond their serum elimination half-life value, and the half-life of the proton pumps themselves (20–24 hours) becomes relevant with synthesis of new proton pumps required for the parietal cell to secrete acid.

Optimal Intravenous Dosing

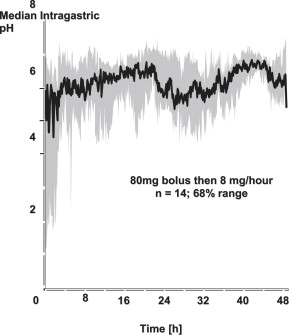

Investigators have studied a large intravenous bolus of PPIs to quickly achieve a high intragastric pH in the acute setting, followed by a high-dose intravenous route of administration to keep as many pumps as possible inhibited over time, thus achieving maximal acid suppression. Gastric pH studies have shown that bolus intravenous dosing of PPIs is suboptimal, and that a dose of 80-mg bolus followed by an 8 mg/h infusion using omeprazole is required to achieve a theoretically optimal sustained target gastric pH of around 6. Similar results have been shown using comparable doses of other intravenous PPI solutions with esomeprazole, lansoprazole (using shorter infusions of 90- to 120-mg bolus and 6–9 mg/h), omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding ( Fig. 2 ).

Results of Randomized Trials Using Intravenous PPIs

Intravenous PPIs achieve more profound and sustained acid suppression than H 2 -receptor antagonists without the development of tolerance. The initial literature had shown mixed results using varying bolus doses of intravenous PPI. The best designed of these studies showed no benefits attributable to the administration of omeprazole, 80 mg, intravenously immediately (before endoscopy), followed by three doses of 40 mg intravenously at 8 hourly intervals, then 40 mg orally at 12 hourly intervals for 4 days or until surgery, discharge, or death.

In contrast, most well-designed and adequately powered randomized clinical trials have shown the efficacy of the high-dose infusion of an 80-mg bolus of omeprazole followed by 8 mg/h for the first 3 days of treatment, in patients having first undergone endoscopic therapy for bleeding ulcers exhibiting high-risk stigmata. The landmark study by Lau and colleagues showed a highly statistically and clinically significant decrease in rebleeding rate from 22.5% in the placebo group to 6.7% in the high-dose intravenous PPI group (hazard ratio, 3.9, 95% CI, 1.7–9.0). This study was stopped short of the initial enrollment for ethical reasons, given the large effect size seen in rebleeding. Nonetheless, the authors also noted trends in improvements in the proportion of patients requiring surgery or dying.

Additional trials have since confirmed the beneficial effects of this dosing, including a very recent randomized trial of high-dose intravenous esomeprazole compared with placebo that involved 764 patients and confirmed the broad generalizability of these results to patients of varying races. Surprisingly, the largest intravenous PPI trial conducted to date, involving 1256 patients, failed to find significant differences when comparing high-dose pantoprazole with ranitidine ; however, pantoprazole showed a better overall score using a composite outcome measure. Possible explanations for this unusual finding could be attributed to the very low rate of rebleeding in the ranitidine group (3.2%) in this study compared with other studies (8%–16%). Also, the patient groups were relatively healthy in comparison with other trials, with only 4% having a history of comorbid cardiovascular disease. The authors also acknowledged potential misclassification of low-risk lesions and methodological limitations attributable to the definition of the primary outcome and the choice of statistical analysis. Significant benefits were found in patients with Forrest Ia lesions attributable to pantoprazole.

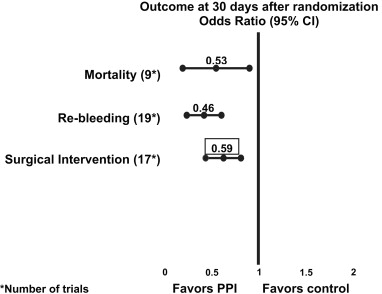

An authoritative Cochrane meta-analysis by Leontiadis and colleagues including 24 randomized controlled trials and comprising 4373 patients concluded that acute PPI use (omeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole) reduced rebleeding (odds ratio[ OR], 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37–0.65; number needed to treat [NNT], 13), surgical intervention (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.48–0.78; NNT, 34), and repeated endoscopic treatment (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.16–0.74; NNT, 34). Furthermore, assessment of the 12 trials that provided data on patients with active bleeding or a nonbleeding visible vessel showed that the PPI significantly decreased mortality (OR, 0.53; 95% CI for fixed effect, 0.31–0.91). This effect related to the results of 7 trials (including 4 high-dose intravenous and 2 high-dose oral PPIs) in which endoscopic therapy was systematically first performed, confirming that profound acid suppression should be considered an adjuvant to endoscopic hemostasis in this high-risk group ( Fig. 3 ).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree