Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have decreased quality of life and high morbidity and mortality. In 2007, the adjusted annual mortality of dialysis patients in the United States was 19%. Although still unacceptably high, there has been a progressive decline in the mortality rate of dialysis patients, particularly since 1999, when the annual mortality rate was >22%. The rate of growth of the ESRD population has slowed. The incidence of treated ESRD decreased between 2006 and 2007; however, the absolute number of new dialysis patients continues to increase every year, albeit at a slower rate. The prevalence of ESRD continues to increase, as does the size of the total dialysis population in the United States. It is estimated that in the year 2020, 142,858 patients will be given a new diagnosis of ESRD, and by the end of that year, more than 750,000 Americans will have ESRD.

This chapter presents an overview of the current recommendations designed to retard the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD); to optimize the medical management of comorbid medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD), diabetes, and lipid disorders; and to decrease the complications secondary to progression of kidney disease including hypertension, anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and malnutrition. These recommendations are derived from the clinical practice guidelines published by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) of the National Kidney Foundation (NKF).

I. DEFINITION AND STAGING OF CKD.

The definition of CKD is as follows:

A. Kidney damage for 3 months or longer, as defined by structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney, with or without decreased glomerular filtration rate (GFR), manifest by either

1. Pathological abnormalities; or

2. Markers of kidney damage, including abnormalities in the composition of the blood or urine, or abnormalities in imaging tests

B. GFR of less than 60 mL/minute/1.73 m2 for 3 months or longer, with or without kidney damage.

In an NKF report, CKD was divided into stages of severity (

Table 11-1). Importantly, the staging system is based on estimated GFR (eGFR) and not on the measurement of serum creatinine. Stage 1 CKD is recognized by the presence of kidney damage at a time when GFR is conserved; this includes patients with albuminuria or abnormal imaging studies. For example, a patient with type 2 diabetes and normal GFR, but with microalbuminuria, is classified as stage 1 CKD. The definition for microalbuminuria is 30 to 300 mg/day (24-hour excretion) and for clinical proteinuria more than 300 mg/day (24-hour excretion). Stage 2 CKD takes into account patients

with evidence of kidney damage with decreased GFR (60 to 89 mL/minute/1.73 m

2). Lastly, all patients with a GFR of less than 60 mL/minute/1.73 m

2 are classified as having CKD irrespective of whether kidney damage is present.

The staging of CKD is useful because it endorses a model in which primary physicians and specialists share responsibility for the care of patients with CKD. This classification also offers a common language for patients

and the practitioners involved in the treatment of CKD. For each stage of CKD, K/DOQI provides recommendations for a clinical action plan (

Table 11-1).

An essential requirement for the classification and monitoring of CKD is the measurement or estimation of GFR. Serum creatinine is not an ideal marker of GFR, because it is both filtered at the glomerulus and secreted by the proximal tubule. Creatinine clearance (CrCl) is known to overestimate GFR by as much as 20% in healthy individuals and by even more in patients with CKD. Estimates of GFR based on 24-hour CrCl require timed urine collections, which are difficult to obtain and often involve errors in collection. Classic methods for measurements of GFR, including the gold standard inulin clearance, are cumbersome, require an intravenous infusion and timed urine collections, and are not clinically feasible. In adults, the normal GFR based on inulin clearance and adjusted to a standard body surface area of 1.73 m2 is 127 mL/minute/1.73 m2 for men and 118 mL/minute/1.73 m2 for women, with a standard deviation of approximately 20 mL/minute/1.73 m2. After age 30, the average decrease in GFR is 1 mL/minute/1.73 m2/year.

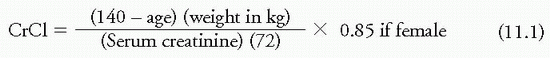

Equations based on serum creatinine but factored for gender, age, and ethnicity are the best alternative for estimation of GFR. The most commonly used formula is the Cockcroft-Gault equation. This equation was developed to predict CrCl, but has been used to estimate GFR:

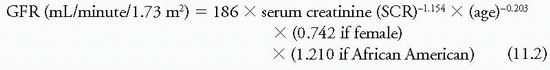

The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study equation was derived on the basis of data from a large number of patients with a wide variety of kidney diseases and GFRs up to 90 mL/minute/1.73 m2. Therefore, the abbreviated MDRD equation is recommended for routine use and requires only serum creatinine, age, gender, and race:

The calculations can be made using available web-based and downloadable medical calculators (www.kidney.org/professionals/KDOQI/gfr_calculator.cfm).

The MDRD study equation has many advantages. It is more accurate and precise than the Cockcroft-Gault equation for persons with a GFR of less than approximately 90 mL/minute/1.73 m2. This equation predicts GFR as measured by using an accepted method [urinary clearance of iodine 125 (125I)-iothalamate]. It does not require height or weight and has been validated in kidney transplant recipients and African Americans with nephrosclerosis. It has not been validated in diabetic kidney disease, in patients with serious comorbid conditions, in healthy persons, or in individuals older than 70 years.

Creatinine-based measurements are currently used to calculate eGFR, but this measurement has limitations in risk assessment due to non-GFR determinants of serum creatinine. For this reason, cystatin C has received attention as an alternative marker for estimating GFR. A recent meta-analysis

examined whether the addition of cystatin C measurements to creatinine measurements in calculating eGFR improved the risk classification for death, CVD, and ESRD. Sixteen studies (11 general population studies and 5 CKD cohort studies) were included in the analysis. Cystatin C-based eGFR detected increased risks of all-cause and cardiovascular deaths that were not detected with creatinine-based calculations of eGFR. Cystatin C-based eGFR and eGFR based on combined measurements of creatinine and cystatin C had a constant linear relationship with adverse outcomes for all eGFR levels below 85 mL/minute/1.73 m

2. Forty-two percent of patients with a creatinine-based eGFR of 45 to 59 mL/minute had a cystatin C-based eGFR of 60 mL/minute or more, and the reclassified eGFR resulted in a 34% reduction in the risk of death and an 80% reduction in the risk of ESRD. This study provides evidence that cystatin C improves the role of eGFR in risk categorization of patients with CKD.

II. PREVALENCE OF CKD.

The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) included 15,625 participants aged 20 years or older and was conducted, between 1988 and 1994, by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The goal of this survey was to provide nationally representative data on the health and nutritional status of the civilian, noninstitutionalized US population. The results, when extrapolated to the US population of adults older than 20 years (n = 177 million), revealed the following findings relevant to CKD:

A. A total of 6.2 million individuals had a serum creatinine ≥1.5 mg/dL, which is a 30-fold higher prevalence of reduced kidney function compared with the prevalence of treated ESRD during the same time interval.

B. A total of 2.5 million individuals had a serum creatinine ≥1.7 mg/dL.

C. A total of 800,000 individuals had a serum creatinine ≥2.0 mg/dL.

D. Of individuals with elevated serum creatinine, 70% have hypertension.

E. Only 75% of patients with hypertension and elevated serum creatinine received treatment, with only 27% having a blood pressure (BP) reading lower than 140/90 mmHg and 11% having their BP reduced to lower than 130/85 mmHg.

In a further analysis of NHANES III data, eGFR was calculated from serum creatinine using the MDRD study equation. The prevalence of the different stages of CKD clearly shows that the CKD population is several times larger than the ESRD population. The challenge for the medical community is to identify earlier stages of CKD and institute correct treatment strategies to decrease complications and slow the progression to ESRD.

More recently it was noticed that the prevalence of CKD stages 1 to 4 increased from 10.0% in 1988 to 1994 to 13.1% in 1999 to 2004 in the US population. This increase was partly explained by the increasing prevalence of diabetes and hypertension. However, compared with 1995, the death rate in Medicare patients with CKD has fallen 40.3% and the adjusted death rate from CKD was 74.9/1,000 patient years in 2010.