- Around 25% of patients start dialysis without adequate preparation within the United Kingdom. This is often due to a failure to integrate care, such as in patients with diabetes.

- The National Service Framework for kidney disease identifies as markers of best practice in the predialysis phase:

- multiprofessional care for at least one year before renal replacement therapy (RRT);

- vascular access at least six months before haemodialysis;

- pre-emptive transplant listing at a glomerular filtration rate (GFR) of 15 mL/min or six months before dialysis.

- multiprofessional care for at least one year before renal replacement therapy (RRT);

- System redesign is required to address the challenges of providing equitable, efficient and high-quality care to people with kidney disease.

- New methods of haemodialysis have emerged. In some units there are patients who are now taking a more independent role in managing their own haemodialysis. ‘Home haemodialysis’ is also being offered in a growing number of areas. This avoids the travel three times a week to and from the dialysis centre, and the option of overnight dialysis at home allows longer and more efficient sessions.

Introduction

Renal medicine as a clinical speciality is a relative newcomer. Prior to the 1960s, when long-term renal replacement therapy (RRT) first became available as a result of vascular access and transplant surgery, clinical care of people with kidney disease consisted of little more than observing progressive pathophysiology, for which there was little treatment. Care of patients on RRT now provides the major workload for renal teams, although nephrologists still have a significant role in the management of acute kidney injury (AKI) and in the investigation and treatment of a wide range of kidney diseases, which nowadays do not necessarily lead to the need for dialysis.

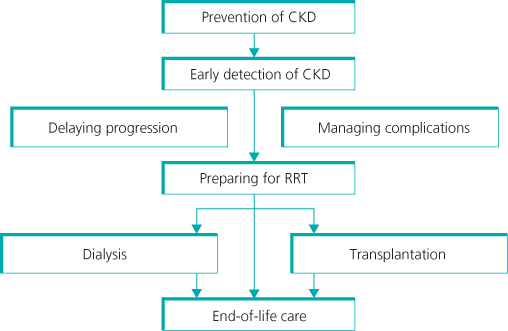

Until the publication of the Renal National Service Framework (NSF) policy in the United Kingdom in 2004/5, initiatives focused exclusively on dialysis and transplantation. It is now recognized that the renal care pathway is much broader. A preventative dividend may be achieved if we had a better understanding of factors responsible for the initiation of renal injury and by the early detection and active management of progressive kidney disease.

There is now a clear appreciation of by how much the numbers of people affected by some degree of chronic kidney disease (CKD) are increasing (Box 13.1). This has been labelled an ‘epidemic’ in some quarters. This large expansion in affected individuals has been fuelled both by global increases in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (Figure A4.1, Appendix 4) and by a better understanding of how to describe the earlier manifestations of CKD—in terms of microalbuminuria, and early reduction in renal function (GFR) (Box 13.2).

Chronic kidney disease

- >5% of population

- comorbidity: 90% HT, 40% CVD, 20% DM

- SMR 36 in unreferred <60 years

- optimal therapy 30%

- potential savings in United States $18–60 bn/10 years

End stage renal failure

- increased at 6–8% p.a.; until mid-2000s—now static in many countries

- acute uraemic emergencies 25%, (see Appendix 4, Figure A4.2)

- pre-emptive transplant listing 3–54%

- dialysis survival 1st year 85–95%

- cost £0.4 bn/year (2002/03) rising to >£0.8 bn/year (2010/11).

Most patients with CKD will be detected by systematic surveillance—measuring eGFR in high-risk groups

- hypertension

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease including heart failure

- patients receiving diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other nephrotoxic agents

- black and minority ethnic populations

- family history of renal disease

Why?

- to minimize associated risks, especially cardiovascular morbidity

- to minimize complications of CKD

- to delay or prevent ESRF

- to avoid late referral (see Appendix 4, Figure A4.2)

The 2007 Model of Service

Services for people with kidney disease in the United Kingdom originally developed in teaching hospitals, mostly alongside academic departments, but have over the last 30 years expanded into some district hospitals. Over that time the number of people on RRT has more than quadrupled. Yet by international comparison, the United Kingdom lagged significantly behind other developed countries in the provision of renal services, especially France and Germany. The renal community of care remains small, with only 80 main renal departments providing in-patient services. Twenty-three of these are combined with a transplant unit on-site. In the last decade, outreach clinics have been established in many district hospitals. Satellite units providing dialysis for stable patients are now much more numerous, and more than half of all haemodialysis patients are now managed in these local units. Despite this growth, for the majority of patients the travelling time for haemodialysis, which is a thrice-weekly treatment, remains in excess of the standard of less than 30 minutes.

One of the major continuing challenges is the development of new renal services alongside the continued necessary expansion of existing dialysis and renal units. Changes in patterns of working to achieve this are both inevitable and increasingly desirable. Renal services need a stable commissioning and planning platform from which to respond to local needs.

Challenges for Renal Health Care

The ‘historical’ centralized model of care is ill-equipped to manage the epidemic of CKD and provide long-term support across the whole kidney patient pathway, much of which by definition will take place in a community setting (Figure 13.1). System redesign was required to address the challenges of providing equitable, timely, efficient and high-quality care to people with kidney disease (Box 13.3). Although the number of consultant nephrologists has almost doubled in the last 10 years, and this growth continues, albeit slowly, investment in education and training of the whole renal multiprofessional team is required to provide a motivated, flexible and empowered workforce to meet the needs of these patients. Of greatest importance is the understanding that community-based or primary care must play an increasingly important role in this endeavour, complementing other groups. An integrated care plan, a central pillar of the Renal NSF, requires information systems that work across institutional, professional and geographic barriers. This can be achieved, but current realization is patchy across the United Kingdom and will require sustained investment and resources.

- Integrating CKD management into other vascular disease programmes

- Expansion of dialysis services

- Increasing the number of kidney donors

- Establishing supportive and palliative care for people with CKD

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree